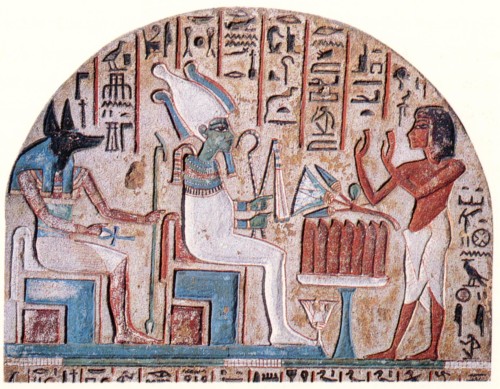

Stele of Nanai, 1400 B.C. (detail)

“Home is a place where the nondescript is sanctified as its necessary place in a system, where sublimity and predictability coincide, and moral grandeur results from the combination of alertness with incapacity for boredom in boring surroundings.”

Robert Harbison

“Thus neurosis exhibits the quest for novelty, but underlying it, at the level of the instincts, is the compulsion to repeat. In man, the neurotic animal, the instinctual compulsion to repeat turns into into its opposite, the quest for novelty, and the unconscious aim of the quest for novelty is repetition.”

Norman O. Brown

“I had a sort of mania for the cinema at that time—I went once or twice a day instead of doing schoolwork. It was exciting going to these big, dark, smoky halls in the city center. I had a real passion for Marlon Brando. He fascinated me as an actor and a sort of mutant—when he first appeared he looked like a new anthropological specimen.”

Roberto Calasso

Interview, Paris Review

The Art of Fiction, #217

“The house has to please everyone, contrary to the work of art which does not. The work is a private matter for the artist. The house is not.”

Adolph Loos

I have a sense that contemporary mass culture, by which I primarily mean TV and film, but also theatre in a lesser degree, and even fiction, has fetishized novelty, an idea of newness, and innovation, and imbued it with an impossible quality of importance and significance. Norman O. Brown pointed out the well known fact of children’s inexhaustible thirst for the repetition of what gives them pleasure, and then notes that adults demand novelty. Children, like animals, seem to have no antagonism in how they view pleasure and repetition. But children have no real memories, or only very limited ones. The adult somehow shifts the experience of repetitive pleasure into something that is deformed by the adult’s idea of self. This is where regression enters the discussion. For the adult has a past, and fixates on it, but fixates on it in relation to some vague (often anyway) project of self improvement.

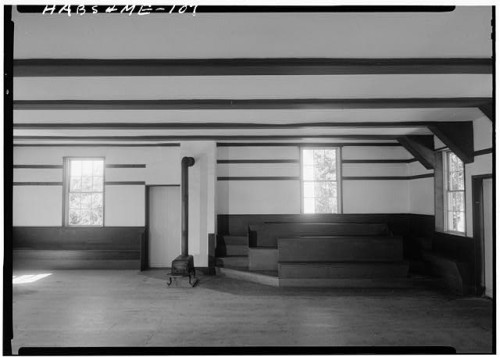

Gerda Peterich, photography. Shaker Meeting House, Cumberland County ME, 1962

Man creates a history for him or herself. The individual’s history. And it often runs parallel and contradicts the collective history within which one lives. And in one sense this flawed idea of personal history is what repression defines. The neurotic individual feels compelled to narratively draw upon an idea of their own history, often if not usually a relatively recent history, in order to make improvements. This is the regressive side of ‘practice’. We’re going to do this until we get it right.

By itself the desire or tendency to repeat is a product of repression. It is the currency of repression being employed to make better that which cannot ever satisfy. Today, the artworks of mass culture seem careful not to puncture this illusion of improvement. I wonder at the mimetic engagement with kitsch stories on TV, for example. The re-narrating is always, it would seem, an exercise in regression. But it is masked.

Y.Z Kami

Aldo Van Eyck, architect. Pastoor Van Ars Church, Hague. 1969

The problem, if that is what it is, with mass kitsch now is that these endless terrible shows are largely written by very young career minded media savy types, who really don’t know what they are writing. They only know what the market might be. What they try to target. Now, the BBC made one of those annoying lists recently, the 100 greatest American films. I’m not sure why just American, but that’s what it was. And while Killer of Sheep made the list, so did Forrest Gump. Presumably, if we believe the BBC, these films were voted on by critics all over the world. What sort of critic thinks Forrest Gump is a great movie? Who thinks that should be on this list and not a single Val Lewton film? But it’s tedious to make lists, and more tedious to point out what is wrong with someone else’s list. But I mention it because it raises questions about criteria. This is a culture now, in the West, in which artworks exist, and some are highly commodified and fetch millions of dollars in auction. But then that’s not really very much money in one sense. The Pentagon black budget is a hundred times what was raised at the last Southby’s auction. The F-35 Long Range Strike Bomber has cost upward of a trillion dollars and it still doesn’t work. But the military doesn’t care, not really, because they are there to spend money, staggering sums of money, and if they fail with this plane, not a single person will lose their job. Money is meaningless in such contexts. And of course it creates jobs, as its being built in over 1200 sights in 45 states. But I digress. the reason Spielberg has five films on the list, is the same reason Forrest Gump is on there. These are films that attracted attention. Firstly they were popular. But that’s a circular argument, I realize. They were popular for a variety of reasons. Marketing, and studio budgets for marketing. But more, because these films invite an easy superficial agreement. There is nothing in them beyond vacuous and anodyne familiarity, a representation of an already agreed upon imaginary ‘real world’. Tom Hanks is an actor whose entire career is compiled of perhaps three expressions, all of them sentimental and wet eyed, and an earnest off screen persona. He is like ‘instant tapioca’. Or powdered milk. But it is exactly his shallowness that launched his career. There is a quality of unreflective self involvement in Hanks, in the shape his mouth takes when he’s not speaking, or in a physical profile that drops him dead center, the mean average for white males in the U.S. His is the domesticated narcissism that grants permission for the viewer to embrace their own narcissism.

A young Roberto Calasso

Hans Hollhein, photo montage.

The idea that the aristocracy imposed about proportion, and decorum, was both partly a scolding of the uneducated masses, but also was their own sense of assumed superior taste finding outward expression. It was the creating of a psycho-spatial distance between themselves and the masses. Uncrowded, quiet, refined, and moderate. But, also modern, rational. The haute bourgeoise looked to emulate this, and there was throughout, I think, an emphasis on social education and manners. If the masses were dirty, then the space of the intelligensia was sanitized, both materially and visually. But also in terms of space. Pietila’s comment is right, the real world of commerce never was to kept completely outside. If the clerestory windows in naves in Gothic cathedrals were there to draw up the eye of the parishioner toward heaven, then the modern Church window was there to remind those worshiping that the real daily affairs of the world were still going on. It was the reminder of obligation to commerce. And manners were evolving into ‘business manners’, rather than court manners.

This idea of everyday business was a defining aesthetic and moral concern for the European bourgeois of the 17th and 18th and even 19th centuries.

“Nothing particular happens in the scene, nothing particular has happened just before it. It is a random moment from the regularly recurring hours at which the husband and wife come together.”

Eric Auerbach on Flaubert’s Madame Bovery

Edgar Arceneaux

As Franco Moretti oberves about Emma Bovery — perhaps the quintessential bourgeois heroine, her affairs only bring her the same banalities as did her marriage to Charles, and more, the same ‘regularly recurring hours’. This was the birth of instrumental thinking. A side bar note here, and that is that if the apotheosis of bourgeois narrative was found in Flaubert, then by the time of Thomas Mann, the novel was still criticizing bourgeois life, and this was true as well in Ibsen say, but it was not until the modernist novels of Bernhard, and Handke, and before them in those outliers such as Von Kleist and Buchner, that the form began to really upset the conventions. However critical a writer such as Ibsen, and a writer of extraordinary skill, the radical was far better realized in the works of Strindberg.

The rise of the star-chitect has coincided with the dismantling of narrative, and with a securitized landscape anchored by fortress architecture and a check point ‘in-between space’. That normalizing of this in-between space, one emptied of meaning or utility, is something I want to return to, below. Now, going back to a fetishizing of novelty, or innovation; there is a connection between this construction of *innovation* in artwork, and regression in the adult viewer, I suspect the ways in which innovation appears is through, literally, an aphasic gimmick or amusement. I cannot think of tragic innovation, or even pessimistic innovation. And partly this is simply that the pessimistic cannot be advertised and sold. The new is fashion today. The way this appears in space, and perhaps in architecture, is by accident in those in-between spaces — that which is between various balkanized and check point bantustans in US urban centers (and increasingly in Europe). The Israeli carving up of Palestinian land is the purest expression of colonial management of space. Today, the space around the average citizen is occupied. The narratives are occupied, and the eye is captured.

Clifford Davis, photography.

OK, end side bar. For what is more interesting, I think anyway, is how these grand competitions and huge budgets become emblems for the disease called man (to sort of borrow Norman O. Brown’s terms via Freud). The fact that capitalism breeds the need for these sorts of monuments to consumption. The Roman Empire, perhaps the first exception to Imperial states in that the Romans fixed and legalized private property. In fact they made it a sort of almost divine ordinance of dominium and imperium. But Rome enforced all this with a huge military. Much as the West does today in the form of the United States, and its subcontracted organ NATO. Today’s globalized and financialized capitalist imperium is also, in reality, enforced by the military strength of the U.S. I find this fact is elided, often, in discussions of global movements and finance. The U.S. only sustains its position through force and threat of force. The medieval landscape tended to impose the market’s logic on both the landless and the landowner. This is the early version of market dependence.

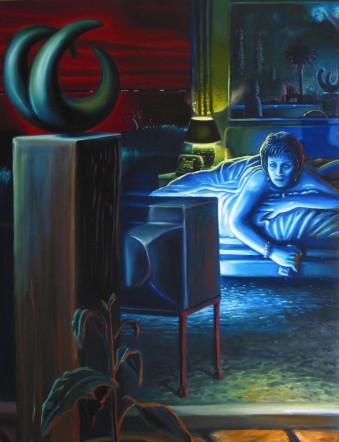

Robert Yarber

But the point is that where earlier forms of Imperialism needed colonial occupation, that is actual troops and colonists to be in place to keep order (productivity), today the financialized colonial order subordinates through less direct means (although military coercion is still a significant factor, as I say). The result of all this is that the habit of invisible right, of absentee power, is cotemporaneous with these other delusions of the individual psyche. To stretch a point, perhaps (and perhaps not), the sight of, say, the Skidmore, Owings & Merrill designed One World Trade Center skyscraper, seems a pure expression of the delusions of capital, and the logical outcome of cultural abjection.

“The days of the child seem to unfold in some sense outside of our time.”

Marie Bonaparte

If one reflects back on childhood, the sense, usually, at least the good memories, even if there are few of those, are bathed in a sort of amber light. In my case, it feels as if my entire youth took place during summer nights. For that is the emotional openness of the young. Even in the most barbaric of societies.

Peter Behrens, architect. Hagen, Crematorium, 1905

Architecture, then, represents something specifically adult in the arts. And like theatre, its a highly cooperative medium. Only one more mediated by societal forces in a general sense. And I find that here, in how a society builds for itself, that something significant is revealed. It leads backward to both primary narcissism, and to the death instinct. And to mimesis and the phenomenon of the Double. “…the ego sees itself outside itself, in an image all the more estranging because it is narcissistic, all the more alienating because it is perfectly similar. What had been one’s own living identity (or identification) becomes, once represented, an exporpriated, deadly resemblance — a frozen mirror, a cold statue.”Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen.

The ancient Egyptians developed an obsessive process of creating images of the dead. There is a dialectic here, in how the double begins as insurance against destruction of the self, of the ego, and reverses to become the uncanny representative of death. The other is seen as the embodiment of the self, out in the world. But emotionally, this is not felt. It is the optical dominance of our historically shaped psyche. Lacan describes a world of statues, as if in a museum, images of stone, hieratic and cold. As Freud said, too, of doubles, that the image of the ego is already a “harbinger of death”. Architecture then is always the building of crypts and crematoriums.

Georg Muche

“Now, this formal stagnation is akin to the most general structure of human knowledge: that which constitutes the ego and its objects with attributes of permanence, identity, and substantiality, in short, with entities of things that are very different from the *Gestalten* that experience enables us to isolate in a shifting field, stretched in accordance with the lines of animal desire.”

Jacques Lacan

Helene Cixous writes that we live in a legalized and general delusion. That fiction takes the place of reality. But this is why all artworks exist. Martha Rosler has said, she fears that people now choose the fiction, the fake. This can be seen in this last month with the outpouring of revisionist history about NATO’s aggression on the Balkans and the anniversary of Screbrenica. David Peterson and Ed Herman were almost lone voices of rationality, and their piece at Monthly Review is very worth reading. But my point is that the real history is there to be read. It cannot be disputed, really. And yet, the public choose fiction.

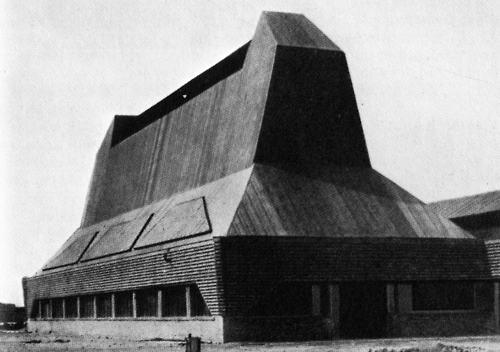

Eric Mendelsohn, architect. Hat Factory, Luckenwald. 1921

If all architecture is, in some way, a form of monument building, then the reading of architecture must include the processional approach. For monuments themselves, there is an unconscious recoil from the stark severity of each. The Lincoln Memorial, in Washington D.C. is difficult to even view without the reflecting pool that leads to it. Monuments always conjure the dead. The obelisk or cenotaph are anti-communicative, because the real content to be communicated is that we are mortal. This relates, then, to this idea of in-between spaces. This is partly the result of mass surveillance, but it is also something more. And surveillance itself is mostly a kind of magical thinking. There are so many contradictions present in the public’s feelings about surveillance that it’s almost impossible to list them all. However, in terms of this idea of the in-between, the space that exists always just outside the CCTV, or police gaze, in urban areas, is the invisible home of the working poor. And of the unemployed. A space that is an ante-chamber to the real world of affluent spaces, and so when one views the grand architectural projects and commissions of celebrity architects, they exist in isolation from the working class. The renderings of these architectural projects mostly erase people. They certainly erase crowds.

AEG Turbine Factory. Peter Behrens architect.

Walter Benjamin in an early set of notes for an essay he never wrote (jotted in 1916 during a stay with Gershom Scholem), wrote that “If there is anything like anamnesis, it takes place among children, whose illustrated picture book is paradise. They learn how to remember…they learn in the remembrance of their first intuition. And they learn about the motley, for the home of remembrance without longing is the fantastical play of colors, which can remain without longing because it is unclouded.” He later changed his mind about the longing and wrote; “It is not without longing and regret, and this tension toward the messianic is the proper effect of authentic art…”

Sophy Rickett, photography.

This is important in terms of our later adult memory. And imagination, and how building is, then, a recuperating of some state of childhood amnesia. Except it’s not that, exactly. Benjamin didn’t think that art allowed for some ideal unclouded vision, some ‘natural’ vision. Rather authentic art creates a longing for that childhood vision of paradise, and in that longing is triggered a new tension of regret, and one that Benjamin connects with the messianic. However that may be, the idea of amnesia in children is a subject that crops up repeatedly throughout Benjamin’s writing. But in this same set of notes Benjamin writes…“Space has no spiritual appearance other than in art.”In that sense architecture is then a spiritualizing of space, but one that cannot occur directly. The adult experiences space through memory, or at least aesthetic space. This is the mimetic narrative, and in architecture that ‘re-narrate’ that we do is highly mediated, more than theatre or film, due to the degree of functionality involved. And that creates second tier memories within that mimetic karaoke in the head, because that narration today must of necessity involve degraded grammar and a lost canon in a sense. Benjamin used the word canon in a particular sort of way, but the main idea here is that one compares experience with past experiences, with learned ideas of the experience of walking through Church or a mall, and with something else, something that is probably narcissistic and forgotten in early childhood. And that becomes a very complex discussion. The point here is that architecture is always an exercise in frustration, in imperfection, and in ambivalence. The functional aspect of building is the lens through which these tensions are re-created. Mimesis, in architecture, is the story we tell of what we have forgotten.

A small note on the Peter Behrens’ designed crematorium above. It is only one of two buildings of any note that Behren’s designed. But he was not without influence and worked as a teacher to both Mies Van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. It is of interest because his nearly iconic AEG Turbine factory, done in 1908, set the style for factory building that lasted for forty years. This may be a slight exaggeration, but there is in Behrens (a notoriously unpleasant and cold man, and sadistic to his family) the foreshadowing of the industrial death machinery of WW1. The first anonymous war. The first industrially designed war. Gropius in a discussion with Stanford Anderson pointed out that Behrens geometic shapes were not from a theoretical basis, and that he was “technically insecure”. It is perhaps, paradoxically, because of this that Behrens’ crematorium is so effective. It is among the least apologetic of buildings of this sort. Levernetz’ crematorium in Stockholm, while brilliant in its Scandinavian severity, is also too modest, finally. Behrens building is almost a dream of Heidegger and Goebbels, and to some degree of Albert Speer. But this volkish sytle, a neo teutonic kitsch is meshed with Behrens idiosyncratic assimilation of Etruscan pottery and sculpture. There are elements, too, of that branch of German expressionism that veered periously close to cartoon mysticism — the Theosophy of architectural expression.

George Schrimpf

There is something in the work of today’s star architects, Richard Meier, Calatrava, Hadid, and back to Philip Johnson certainly, and Richard Rogers. I thought about Robert Hughes story of meeting Albert Speer. And what Speer said of Philip Johnson; “Johnson understands what the small man thinks of as grandeur. The fine materials, the size of the space.” It is natural that Speer would see something of his own vision in that of Johnson. He would not identify with Frank Lloyd Wright, or Luis Barragan, or Louis Kahn or Oscar Niemeyer, or Carlos Scarpa. Nor with Le Corbusier even. There is something that separates the newly discovered fascist leanings of Le Corbusier from the narcissism of Johnson or Norman Foster. For they are capitalist authoritarians, ideologically close to fascism, but whose style is different. Le Corbusier saw a purifying of the eye (and removal of the masses) while Speer and Johnson saw god given superiority and grandeur and their entitlement. There is a distinction, I think.

“It comes about that the products of technological progress do not find immediate application in building but are first scrutinized by ruling aesthetics…”

J.J.P. Oud

Peter Kayfas, photography.

Benjamin said that each epoch dreamed of the one to come and that the dream invariably took for the form of primal history (meaning a classless society, and no doubt an unrepressed society). For Benjamin, the *new* (the innovative) is then made up of the stuff of collective history, and its *ur-forms*. Gevork Hartoonian writes: “Here Benjamin seemingly alludes to his idea of wish images in which the new presents itself in the guise of essential forms, and aspects of culture which are experienced collectively. Thus he suggests that fashion, a major epitome of modernity is nothing more than the eternal return of the same.” It is the eternal return of the same. Gevork Hartoonian has written that the *new* in architecture is a desire for a primal past when Nature was not separated from daily life, and that this wish, this dream, also contains the desire for the materials of building, their repressed state (as he put it) to reveal itself. He goes on to note that cladding on today’s buildings where the object then becomes an image, and often a virtual image. This is really the crisis of modern architecture, or perhaps the crisis is really that of post modern architecture. The arrival of iron in the 1930s (it was earlier, but that delay itself is a topic) signaled a recognition that the age of stone building had reached exhaustion.

Allow me a long quote here from Hartoonian’s book Crisis of the Object: Architecture of Theatricality.

“The proliferation of computer technologies has shifted the interest of architects from

the tectonic of the final product to its surface. For many, the early modernists’

concern for the impact of industrial building techniques on architecture is no

longer a formative theme. This line of thinking is supported by the belief

that the building industry, especially in America, has been unable to introduce

new materials and techniques, thus the impossibility of changing the “image”

of architecture beyond that of modernism. From this point of view, the use of

glass, steel and even new synthetic materials in the architecture of the past

two decades has not pushed the tectonic thinking beyond what the Dom-ino

frame has to offer. By modifying existing techniques, however, the building

industry is slowly accommodating its products and techniques to the architects’

esteem for virtual images. Thus we observe the moment of departure from the

postmodern concept of both–and, and architecture’s entry into the world of

spectacle, i.e. theatricalization, the expressionistic forms of which can be associated

with the virtual fluidity of capital and the information industries as

capital achieves global domination.”

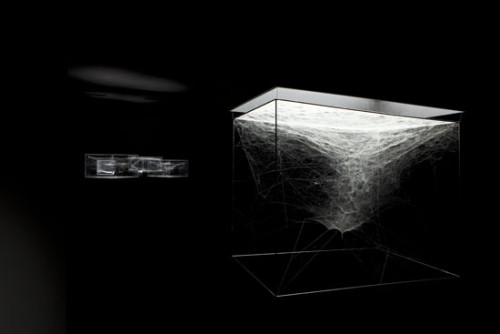

Tomas Saraceno at Esther Schipper gallery, Berlin 2013.

The entry into the Spectacle probably happened earlier than whatever is being posited as the start of the post modern. But it is not just virtual fluidity as the image of global capital. It is more the schizophrenic place-less vertigo of a propriator class adrift in their solipsistic baby speak. It is the building of digital fractyls, the tyranny of computer generated designs that architects, increasingly, see as acceptable pseudo or virtual affects. The affect IS the buildings aesthetic. An almost nihilistic aesthetic of iPhone level complexity. Global capital, the capitalist coercive and predatory system of circulating images and human misery is expressed, then, in the massive visual gluttony of Zaha Hadid.

Adolph Loos once said only monuments and tombs are really architectural art. I suspect the truth of that statement was not what he had in mind. But maybe it was. The debates that arose in the later part of the 19th century, and on through the first World War, and even after, all involved questions of technology. The burden that was felt had to do with questions of progress. Behind everything lurked the onus of the new. And the new meant progress. Today the effects of computer programming in design privileges perception over any ideological issues of construction. The shift is profound. The post modern building is viewed (or read) as a text, and one that is illegible.

Benjamin saw in Kafka something significant in terms of the pressures of ‘progress’. Kafka did not write of progress. He did not see his age as an advance over earlier history. But he wrote a timeless world. And his production or generation of space (remarked upon extensively by both Adorno and Benjamin, and later Lacan) was a psychic space. The world of Kafka is always a stage. It is a staging for the scene of the primal crime. It is the space one finds in Pharaonic Egyptian art, often. Timeless, but also multiple times occurring at once.

Harry Sussman wrote : “Kafka becomes the psychoanalytic explorer of prehistory.” And this was Benjamin’s feeling, too, when he writes “Oblivion is the container from which the inexhaustible intermediate world in Kafka’s world presses toward the light.”

Dirk Braeckman, photography.

There is something hugely important going on in Kafka, and how it relates to discussions of architecture, progress, and the uncanny. Sussman notes the similarities in Kafka to the Jewish mystics in the Zohar as they wander in pairs, at night, through an alien landscape of the exile. The communicative aspect of building is always linked to something from the past. From both our individual histories and from the dawn of history. The space in Kafka’s world is that of theatre. The post modern software architecture of global capital is one that air brushes aside the human, and collapses space. Or worse, really, diminishes the individual. Gothic cathedrals were meant to humble the worshiper, to allow a transformation of vision. The industrial revolution signaled something brutal and exploitive, but it was mediated with questions of progress, and something vaguely Utopian. The post modern has abandoned Utopia, and replaced it with affect. With an affect that undermines the foundational aspect of all building. The utility is class segregated. It doesn’t humble, it frightens and threatens.

When Calasso writes of his love of movies, the discovery of Brando, he is writing of that curiosity that is beaten out of adults somehow. Film is so pervasive now that it is revising how we tell our old stories to ourselves. The experiences we have are re-processed as film strips now. But increasingly, the corrective aspect of cinema, the dream state of that flickering 24 frames a second, is being lost and with it that love of cinema. The love is now digital expertise.

The later Freud saw anxiety precipitating repression. This was (partly anyway) a reversal of his early writing on childhood. It is also were Lacan revised Freud. Either way, childhood in western society takes place, symbolically and most often literally, in the home.

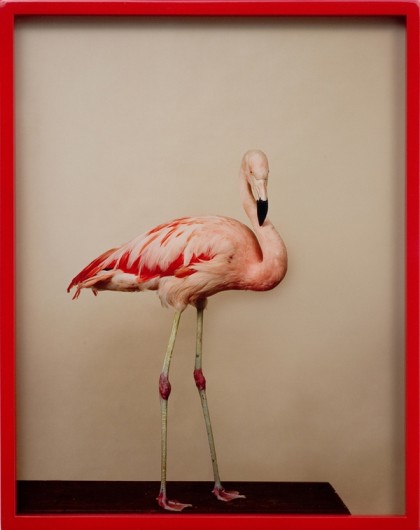

Elad Lassry

And so, at the conclusion of the *new* and *innovative*, one arrives at the idea of the home. I think there is much yet to be written about the poetics of the home. It is a constant in mass culture, in terms of representation, and yet it is always the background. It is not easy to foreground it. And partly there is the word itself; *home* means many things, is used many ways. In western society, over the last couple hundred years, the bourgeois notion of home has at least some clarity. The English home is the site of Sherlock Holmes as well as Gary Oldman’s Nil by Mouth, and earlier the world of New Grub Street. The aristocracy are not associated with having homes. They have houses, estates. In Holland and Belgium, the home is both externally pathologized (the penchant for brick in Belgium was discussed by Max Borker in the current issue of Uncube) while the interior is cleansed. The homes of Holland and Belgium, and partly of Switzerland are equated with a bunker morality about family, a sort of pride in homliness. And it does speak to the lack of innovation in the building of homes in the countries of the Benelux. The German home is most always nostalgic, or in protest against that nostalgia. Perhaps the most balance is to be found in Mediterranean homes. In Greece, or southern Spain, or Italy. Worthy an entire dissertation is the difference between a riad in Marrakesh and the homes of England and the U.S. In the U.S. the home was really a house, and it was suburban. There is a kind of schizoid ambivalence in the U.S. about home/house. It became a renter culture by the 80s. I’m from the left coast, a southern Californian. The place NOBODY comes from. The idea of home was always an elsewhere. I am that rare thing, a native of Los Angeles. Mike Davis is the most famous native of El Lay, and has the best critique of its history. But I digress. If one examines the psychological space of the home today, it is easy to note that extreme heterogeneity of the U.S. home. Firstly, because so much of the past has been demolished. And second, because what has replaced it is often intentionally *new*, which really means without history. Housing exists, but not many homes. And *housing* smacks of crowd control and warehousing. If Belgium is the nation of brick family homes, then the U.S. is the nation of warehouses. And the warehouse is, in fact, the predominant icon for American protestant zeal in industriousness. The industrial park (sic) is the U.S. contribution to both gardens, factories, prisons, asylums, and catacombs. The small business warehouse is the ubiquitous symbol of society without a home.

Lewis Baltz, photography.

“I’m more interested in narrative in relation to the kind of things I photograph, things that almost can’t be called narrative. I often describe my first book The Pond as ‘narrative landscape’: you step off the pavement into the unpaved area, you wander around a bit and then you go home. I think simple stories are sometimes more seductive than complicated ones which can get lost. The running order of a number of projects I’ve done is virtually narrative: you start here and you end here and certain things happen in between.”

John Gossage in conversation with Lewis Baltz

I think this is an important observation of Gossage. And I’ve said the same thing in a way since I started this blog. Everything is a narrative. Or rather, there is a narrative to everything, and without that one is left with a surface affect. And that might be, really, why post modernism is so nihilistic. The warehouse is also the logical use of in-between space. And the U.S. is the society of in-between space. The space in Kafka is timeless but specific, while in an ahistorical West, today, the space is either an affect, a hieratic script to be read, by those whose vantage point allows the panorama, or it is a containment area, a point of transit, embarkation, disembarkation, and the one constant is the holding tank. The policing of the public is reflected in a growing impulse to police from all corners of the ideological spectrum. It is a nation of guards, of rent-a-cops and private security personnel, both literally, but also, more significantly, psychologically. Even those most hunted, most insecure, often position themselves to guard something. People with nothing to guard, guard their nothingness. So deeply has the authoritarian ruling elite inscribed their sickness on the general population.

Great stuff as usual. Your writing is getting more and more lucid. Its off topic but was wondering your thoughts on Mr. Robot. I was enjoying the second season of true detective but stopped watching after mr robot came on. It goes after the similar issues much more directly and passionately, no coy posturing. It’s sincerity is rare and refreshing. I’m shocked it got made.

David……

Funny, I was going to write about Mr Robot next post. Its rather remarkable, really. And I cannot for the life of me figure out how they got it produced.

John, how in the hell do you find such amazing art? Please share.

This gives some insight into the creator etc…http://www.fastcocreate.com/3047491/how-the-makers-of-mr-robot-cracked-the-code-of-a-realistic-hacker-drama

@joanna….those sorts of articles depress me profoundly. I find this is the grammar of mainstream kitsch, and it feels like leeches attached to my brain after the first paragraph. So contra to insight, its sort of blighted my appreciation of the show. Though I am sure I will recover.