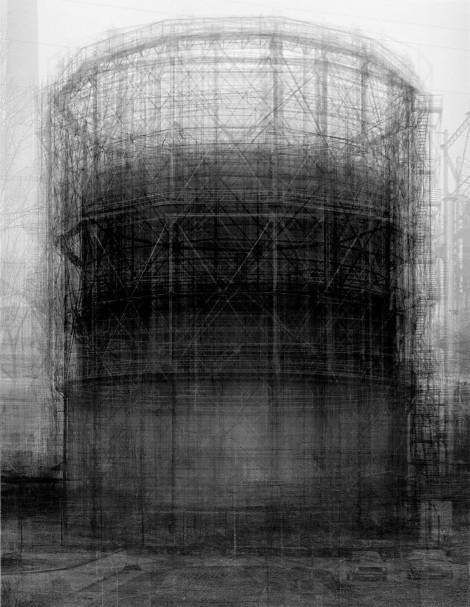

Idris Khan

“Of course, most people don’t really have to come to grips with pride and fear. But artists do, because as soon as they’re alone and solitary, they feel fear.”

Agnes Martin

“At least since the Enlightenment, and in some cases before, modernity

has signified a process of ‘bringing to light’. The dark spaces of

superstition and prejudice must be made to quail before the light, just

as the wolves must be made to stand back from fear of the fire. No

secrets are to be left untold; transparency is all. If you take to hiding in

a cave, your motives are no longer to be seen as an understandable

defence against incursion; rather, you are choosing, unacceptably, to

renounce the onslaught of the modern and to remind us of a past which

modernity wishes above all things to forget. The cave is redolent of an

unenlightened primitivism…”

David Punter

“Terrorism and the Uncanny, or,

The Caves of Tora Bora.”

“There was a kind of presentational quality to the language which I think we were very influenced by. We had a similar attitude toward language, which has to do with a feeling about the spoken word as an almost shamanistic act, incantatory, ritualistic, as opposed to the theatrical [dialogue] tradition… We had a very high estimation of the idea of the word itself coming through the medium of the actor.”

Murray Mednick

A recent visit to the Metropolitan Museum in NYC, yielded three epiphanic moments — the first was the Bill Traylor’s wall, on which hangs his modest (in scale) Black Jesus. The second was Tintoretto’s unfinished Doge Alvise Mocenigo, Presented to the Redeemer. On a certain level these two works share a commonality of spirit, and of a certain quality of menace. The Tinteretto is also unfinished, which lends it an additional aura of mystery.

Gillian Carnegie

“If Egyptians were White, then all these forementioned Negro peoples and so many others in Africa are also Whites. Thus we reach the absurd conclusion that Blacks are basically Whites.”

Cheikh Anta Diop

The narratives of corporate based news, both on TV and the internet, is increasingly repetitive. Hillary’s campaign is eerily like Bill’s first run, and the coverage of Syria or Ukraine feels absolutely interchangeable with Iraq five or even ten years ago. The very same storytelling tropes are applied to these essentially, and increasingly boring elections between old white people fighting each other for the soul of the Nation, against a backdrop of Colonial plunder.

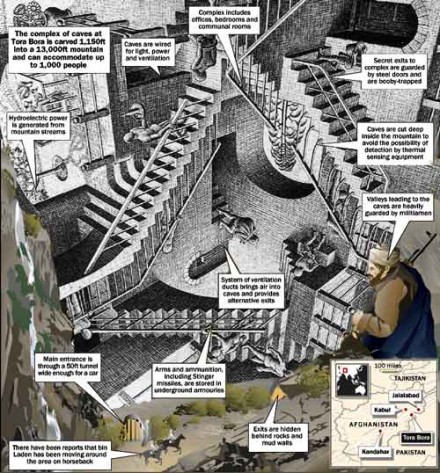

When the first version of Osama Bin Ladin’s life story was rolled out, there was a clear uniformity to detail. Whether it was CNN or BBC World, or FOX even, the essential details were the same. That changed within a few years, but only in cosmetic alteration. More important, the tone and the image presentation, as well as the image itself, were never changing. The repetition of certain words or phrases (Tora Bora, et al) were banged on and emphasized. The same crew cut retired military men were trotted out at each station or network, to say the same things, the same field reporters with the same hair and almost identical faces were given quick ‘field’ spots. The caves of Tora Bora were quickly appropriated as essentially an important leggo block to attach to the propaganda machine-news-a-thon. Tora Bora became, in the U.S. imagination, what King Arthur’s castle had once been to English speaking boys. It became also, something else at the same time. It was an imaginary grotto, or hidden sanctuary, a fairy tale explained with diagrams and illustrations provided by CNN.

Bill Traylor

For the MFA hegemony is mandating a certain snapshot of reality. The gallery owners and high end collectors are uniform in their patterns of valorization. Just as Hollywood is relatively consistent in how they choose projects and directors and show runners. The new High Line Park, a mile and a half city park built on a former railroad trestle running along the far west edge of downtown Manhattan, is almost the perfect expression of the new class of super rich who are remaking Manhattan as a playpen for the millionaire class. Look down on the poor…literally. Designed by Diller, Scofidio and Renfro in 2009, the High Line is the new object of literal class segregation as well as ironic post modern architecture replete with a semiotics of new white benevolence and responsibility. It is made to be walked while wearing natural fabrics and drinking ten dollar Almond milk and Aloe super-food refreshments. Archello describes The High Line thus: “The High Line surface is digitized into discrete units of paving and planting which are assembled along 1.5 miles into a variety of gradients from 100% paving to 100% soft, richly vegetated biotopes. The paving system consists of individual pre-cast concrete planks with open joints to encourage emergent growth like wild grass through cracks in the sidewalk. The long paving units have tapered ends that comb into planting beds creating a textured, “pathless” landscape where the public can meander in unscripted ways.” This is rather telling, really. The public…meaning the affluent…can meander in unscripted ways. What exactly might that mean? It is a cleansing project, a purification project. On a material level it is a way to survey one’s kingdom, but on another narrative level it is, like the entirety of Dumbos, now, a way to decontaminate the psyche. There was a very thoughtful piece in The Guardian by Olivia Lange (save for one odd pseudo feminist aside about the ‘macho’ posturing of the Ab Ex guys — the same guys Martin loved and respected), on the artist Agnes Martin …here: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/may/22/agnes-martin-the-artist-mystic-who-disappeared-into-the-desert

Adam Helms (multi media).

I thought of Martin a number of times while I wandered the city this past ten days. Walking past the White Horse Tavern, or near Coentis Slip. I additionally thought of Rothko and Pollack and also of the Off Off Broadway theatre artists such as Murray Mednick and Sam Shepard, Ronnie Tavel, Joe Chaiken, and Maria Irene Fornes. These were artists engaged, each in their way, with both personal vision (and madness), but also with and in conjunction with society. With a society that was found to be conformist and repressive. Institutional society as the enemy. One would be hard pressed to find such artists today. Certainly one can’t find them, the few that exist, without a lot of searching. Mainstream culture is vetted for radical qualities of any sort.

And this leads me back to Traylor and Tinteretto. There was an intractable terror built into Tinteretto. The greatest, perhaps, of 16th century Venetian painters (though usually regarded as inferior to Titian and even Veronese), his work was both garish and subtle. The almost lurid colors and exaggerated human forms were laced with a highly developed vision of the uncanny — with the uncanny as a kind of knowledge (per Punter). John Jervis has written about the tension at the border region of figurative and literal. Tinteretto is the precursor to Baudelaire in that sense. And perhaps in hindsight all mannerist artists are precursors. Titian was Orson Welles to Tinteretto’s Joseph H. Lewis. Phillipe de Montebello called Titian the greatest of all painters. He added, ‘in certain moods’. And there is a case for such an evaluation. But looking back, does not Velasquez and perhaps even Tintoretto seem more compelling? Velasquez was the equal of most anyone, technically. Tintoretto far less so as he worked quickly, loosely, and seemed far from obsessed with finished detailing. But is it not just that hurried stroke of the brush that makes him seem so modern? So out of time, both his and ours.

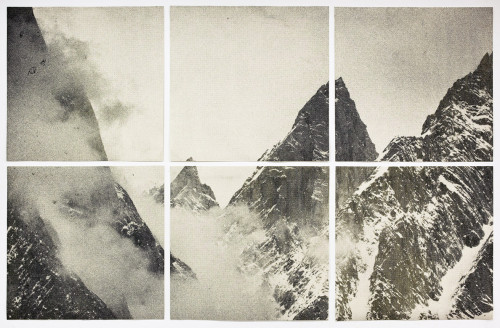

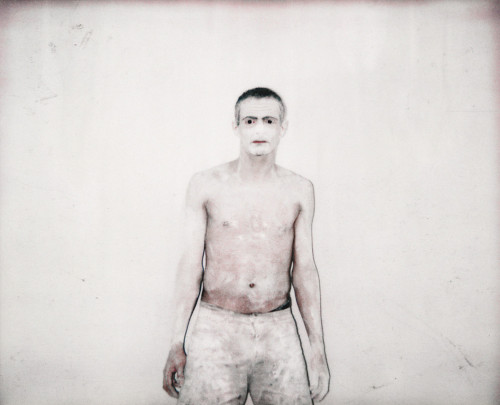

Milo Newman, photography.

“The spectral can figure a state of ontological undecidability or tension, where there is an

insistence, a presence of whatever resists us, recalcitrant to our understanding.”

John Jervis

Tintoretto’s unfinished ‘Doge Alvise’ is a work around which, not surprisingly, debate has swirled. X-radiography, done in the 1940s, revealed several alternative groupings had been stenciled in by the artist. Why the painting was never realized fully is something of a mystery, but even if one accepts some of the expert analysis, it would remain a deeply disturbing work. And one suspects the driving force for this is that plague figured as a central theme in the work (the background figures on the stairs, mostly obscured are possible symbols of the pestilence that hit Venice in 1757). The plague killed Titian, in fact, a seminal inspiration for the still young Tintoretto. That some of the heads were completed by his assistants seems probable, but as a kind of palimpsest, a riddle and puzzle, the painting retains a great power despite or in-spite or because of all these factors.

Agnes Martin

There is much to be discussed in this light having to do with the processing of time, but for the purposes of a quick examination of the great American city today, what is more significant is the retreat from this sensibility of resistance. The contemporary artist, or those embraced by the mainstream (and increasingly by the mass public) is one who flatters the system. The artist, when one thinks of an Agnes Martin for example, is one who senses something menacing in society. It has always struck me that so many artists of the 20th century spent their childhoods in vast big sky territory; in the plains and prairies of the Midwest, or Pacific Northwest, or New Mexico and Mexico. Places where Nature loomed both as spiritual guide and a force of destabilization. It is always useful to reflect on how certain artworks; in various mediums, change over time. Hitchcock, in film, for example, was seen, in some circles, as simply an exquisite technician. But now seems startlingly critical of bourgeois refinements and taste. For the form of his films, in both their technical virtuosity, and in their forensics of a prevailing idea of the ordinary, feel both far darker and more luminous than when they first came out. The insights of Godard and Cashiers seems prophetic today. I think the best films of John Boorman look better today, the work of most Pop artists looks worse. The color field, or West Coast painters like Diebenkorn and Frankenthaler look better, and Agnes Martin looks better. Poets such as James Wright increase in importance while perhaps James Merrill, Hollander, and probably Ashberry diminish. William Carlos Williams seems more important than ever. But it is too much a parlor game to make such lists. The point is, following the sixties, the radical qualities in American art migrated to small affluent college towns in places like Northern California. The city that had been a home to immigrants, migrating poor, and the disaffected was no longer welcoming. Gradually, after 1980 say, the city was going to be cleansed of undesirables. Reagan started his second term in ’85, Koch was mayor of NY, and soon followed briefly by the Dinkins hiccup, and then by Giuliani in ’93 — the Mayoral equivalent of Reagan in a certain sense. In L.A. it was Tom Bradley, the longest serving L.A. mayor, the first black mayor, an ex cop, and a hugely contradictory and complex figure. But mayors in L.A. do not hold the same symbolic significance that New York mayors do. If John Lindsay was the last real supporter of the arts, the last liberal, and a patrician friend of the poor (symbolically, mind you) then today there are only figures like Bloomberg and now DeBlasio who resemble nothing so much as war lords carrying out the bidding of the extremely rich.

Agnes Martin

Now, it is important to keep the backdrop of U.S. imperial propaganda in mind here. Christopher Black (in a terrific new book written with Andre Vltchek and Peter Koenig; “The World Order and Revolution“) wrote … in regards to the U.S. resolution to refer criminal action against the DPRK..“The report itself is an amazing document, not only because it is entirely contrived, but also because the ‘crimes’ which the Commissioners allege take place in the DPRK are exactly the conditions that exist inside the United States itself.” This is exactly why the role of artists must be one of resistance to the status quo, not accommodation. This is also why the pretend-left, the pretend art, of such media darlings as Molly Crabapple is so pernicious. It is also why the ongoing and seemingly never ending appropriating of stories of suffering by western White liberals and the unthinking embrace of this colonial intellectual and creative pillage (mirroring the material pillage) is exactly relevant to discussions of things such as The High Line, and even, as I hope to make clear, to Tinteretto and Agnes Martin, or dozens of other artists whose sensibilities are in opposition. It is almost never the message that matters — it is everything else.

High Line (photo courtesy of Telegraph uk.)

The sense I have of life in American big cities is one of sensory assault and the constant manufacture of anxiety. Firstly, both LA and New York are shockingly noisy. They are loud. They are unrelentingly loud. That endless din is reminiscent of prison and of county lock ups. One sign of wealth is the ability to buy quiet. To get soundproofing on your double glass windows, or ceiling, to just to have the space to distance oneself from the din.

Tintoretto. “The Doge Alvise Mocenigo, Presented to the Redeemer.” 1507.

“What comes into view is a *foreigner*, as odd as he is subtle, and who is none other than the alter ego of the national man, one who reveals the latter’s personal inadequacies at the same time he points to the defects in mores and institutions.”

And this is a very astute insight. The secondary drive that fueled the sadism of the European conqueror. The self hatred.

OBL, cave dweller.

“We need to understand that five hundred years of humanism may be coming to an end as

humanism transforms itself into something that we must helplessly call post-humanism.”

Ihab Hassan

Katheryn Hales calls the post modern urban landscape one of *hyper-solicitation*. So deeply engrained is the idea of property, that the populace today sees themselves, essentially, as property. They’d like to believe they are the owners of themselves, but it is the ownership part that is disturbing. The problem, actually, with a lot of theory on the ‘post human’ is that behind this thinking lies the hidden figure of Capitalism. Or property relations. Even terms like responsibility are couched in ideas congruent with ownership. Own your mistake. Own your desire. I mean, what if I don’t want to own anything? Can I rent?

Antoine D’Agata, photography.

“…rationality taken to extremes and yet…remaining abstract; at the same time this corresponds, in its abstractiness, to the latest capitalist style of thought. It corresponds to the capitalist planned economy and similar anomalies with which capitalism reaches for the forms of tomorrow in order to keep those of yesterday alive. This kind of objectivity, of course, achieves, in the economy and in architecture as well as in ideology, nothing but sheer facade; behind the built in rationalities the total anarchy of a profit economy.”

Titian. “St. Margaret and the Dragon”. 1559.

Bloch also called the new architecture unheimlich (uncanny). He wrote…“the big window does not just shed light on the quiet table but also on the lives of those without one.” Bloch saw in the upper bourgeois aesthetic, one of faux progressivism and objectivity, a style evocative of fascism. This is interesting because of the enthusiasm of the super rich today for architectural innovation and excess — under cover of responsibility and eco friendliness, and more, really, to the hyper solicitous as an ideological virtue. Grand star architect projects of today could well be what Bloch wrote of here, in the 1930s…

“an architect’s smugness which has definitely not grown out of politics, but out of technoidally progressive expertise and the desire for its application, but which likewise propounds, even if in other words, a kind of ‘peaceful evolution of capitalism into socialism’…but this seems a false directness, namely none at all: seeing a piece of a future state in every sliding window, it obviously overrates the technical neutral and underrates the class based elements.”

Frederic Schwartz quotes Bloch..“Only immediately afterwards can I calmly hold such things before me, turn them around in front of me, so to speak. Thus only the immediately past is present to me, corresponding to what we, seemingly being there, experience.” The ideas of nonsimultaneity are complex, and finally, my point is that really, what is needed is what Benjamin did with (or wanted to do) with The Arcades Project. The past cannot be the fixed point from which, as Benjamin said, “politics assumes primacy over history”. The age of mass manipulation is revealed most acutely in cities like New York. Where once the artist’s role was to mediate the assault by turning its energy back upon itself, today the artist is mostly an aspiring young businessperson. Clever, facile, ambitious, and malleable. There is a sort of tacit trusim out there that the culture is indeed trivial, even stupid, and yet, few people seem to mind. Few people seem to believe that they are victims of the non-stop culture machine. Few believe advertising affects them. Part of this trope lies in the fact that marketing people design their commercials and campaigns to achieve just that. To flatter the viewer into thinking he or she is special, and different. To make the intended viewer believe the commercial is not really for them. Its for all the other stupid people, of which I am not one. Most people I know are indifferent to mass culture, even those who, nominally, work for this sector. Partly this is the product of fatigue. I find the vast majority of those who live in big cities to be tired, both mentally and physically. There is an affluent class, of course, who have time for leisure, for visiting health clubs, for buying cute knick knacks and even shopping for improvements to their kitchen, or to get new clothes for their kids. It is an odd fact of today’s class segregation that young white mothers pushing overpriced strollers, wearing the uniform of faux modesty — sans make-up, have become the symbol of a hierarchical system of class violence. The display of relaxation in a climate of such mass struggle and angst and despair, even, feels acutely insensitive and even, I think, aggressive. Which takes me back to The High Line park. For this is the symbol of the new New York. Or at least the re-engineered Manhattan.

Alan McCollum. (Fredrich Pretzel gallery).

It feels as if mass culture no longer has an organic history linked to actual places or people. In even the bad kitsch of previous eras one could detect the residue of real life, of an actual history — of work and play and of community beliefs and values. This is not really so today. The industrial revolution could be found, for nearly a century, in various incarnations, in cultural products. The assembly line, the factory, the Union. These were buried in artworks both in form and content, though perhaps more tellingly in form. Kracauer’s analysis of the Tiller Girls (an early version from Germany of the Rocketts) for example (another borrow from Frederic Schwartz book Blind Spots)saw the mirroring of Taylorized labor. “Since there is no more community, there is no more spirit in ornament”.

Kracauer

In other words, it is not the interior of the given conditions (Schwartz) but rather something that appears above them. It is the *mass* and not the *people*. The elements that make up mass culture today are not born from an organic whole that is an expression of history. This is hugely significant, but also extremely difficult to tweeze apart. For in and of itself, (per the Benjamin quote above) this is not bad, because the fixed point of reference cannot and should not be the patrician high culture of the previous ruling elite. Today, the mass sporting events that have reached the status of ritual or celebrations of national identity, are equally empty in the sense that they are manufactured independent of the audience. These spectacles are not expressions of the society. Kracauer saw these new products as ‘ciphers of capitalism’.

Stephen Balleux

Mass culture then is only an expression of subordination. It is also part of a process of dis-enchantment. As a side bar note, one of the mechanisms, running on auto-pilot today, is to immediately digest critiques of itself, appropriate and neutralize. I’ve read two separate short essays recently that included snarky comments about the word ‘dis-enchantment’. A sure sign the concept has value. Kracauer was an influential thinker for both Adorno and Horkheimer, and a thinker deserving of renewed interest. Today, in cities such as New York, a new hermeneutics is called for, not least because it will be so difficult. One of the reasons it will be difficult is that the very idea of *reason* has been so degraded. For *reason* is now purely instrumental, purely outside history in a sense. Of course nothing is outside history, but just because of that the reading of daily life is now nearly totally opaque. The secret of mass culture today is in the form, but that form is nearly always intentionally hidden. The High Line park is an example of a project that hides its expression as a symbol of post modernity and of advanced capitalism. Historically, per Schwartz again, the experience of WW2, of National Socialism, created caesuras of exile, forced migrations of people, genocide and the concurrent rise of Western militarism. The interstices fill up quickly when looking to impose models of historical explanation.

Since I am mostly concerned with art and culture, it means my own reflections on these questions is going to foreground this area of human life and society. For now, I will end on an observation that links to contemporary film and TV. Bela Balazs was a Hungarian Communist, an associate of Karl Mannheim and Lukacs.

Joakim Eneroth, photography.

“With time, the invention of the art of printing books has made the human face illegible. Men have read so much on paper that they have been able to neglect this other form of communication.”

Bela Balazs

He saw the complexity of the human face replaced with what he termed the ‘countenance’. It is not just the face, though, today, it is the body as well. Both are fetishized and simultaneously ignored. Balazs saw film as a new entry point to a re-acquaintence with the language of gesture and facial expression. Today the world is viewed on screens in the West. And through the screen is learned a screen language — but it is a language of abridgment — it is, as Kracauer saw it, a grammar imposed from above. Notions of beauty and ugliness, of threat and security, are all learned in this new shorthand. And this screen medium is outside history, at least in terms of reason. Of analysis. Now the advent of talking pictures, sound film, changed the model again, very quickly. The advances in optical technology over the last seventy years have altered ideas of almost everything. Daily life in the cities of the West, in particular the U.S. has become more and more mystified, on even the most basic level. For what does it mean today to ‘read’ someone’s face? Sitting on the E train this week, in a subway car with maybe twelve people, I’d say ten of them were staring at their cell phones. And when they looked up, what was on their face? They were checking to make sure they had not missed their stop, usually. But how does this relate to photography and to painting? Or to theatre, for that matter? I see films and plays that are, in their entirety, producing work of (per Balazs) ‘countenance’. The imposition from above of an idea of the whole has rendered life a continuous process of short hand encoded reading. The ‘expression’ of human life is retreating — has maybe already retreated, to a place so buried as to not be again excavated in any meaningful way. At least not in the terms we have learned to think of it.

Very very good. (thanks for the mention 🙂 ) Very interesting. By Bloch do you mean the French communist historian, member of the Resistance, shot by the Nazis, Marc Bloch?

Ernst Bloch. https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/Illumina%20Folder/kell1.htm

“Few believe advertising affects them”

Advertising absolutely affects me. It makes me physically sick. I have never in my life been able to watch TV or blockbuster movies, without feeling awful. I can’t go into shopping malls anymore. They change me. They make me ill, but also self-conscious and embarrassed. I can’t read magazines in a doctor’s office, they make my brain go numb. I get anxious. If I don’t feel sick, I am incredulous. I haven’t watched TV in years and years. Every once in a blue moon I will be at someone’s house and a TV will be on and I will see an ad or hear one on the radio and I will die inside of shock that people actually get roped in by these ads. I mean, these ads are so blatantly stupid, but not only that, a lot of them are blatantly fascist.

I don’t know how you do it, John. You watch a lot of bad stuff that you are very critical of, and I realize you are able to analyze what is going on in the society through the popular culture, and it is important to have that eye and to critique and teach this sort of critical thinking, but I can’t sustain that kind of exposure. My brother listens to a TON of music and watches an enormous amount of television and film. I rant about popular culture with him on occasion, and he has said to me, “you know, you have a lot of interesting things to say and you are probably right about a lot of them, but you would hit home with your statements if you actually watched more popular culture.” Well, I can’t fuckin do it. I get so bored I want to die. I never could, and trust me, I’ve tried. And I still try (while simultaneously trying not to).

And I think you are absolutely right that advertising affects us, and absolutely that it clouds our ability to think narratively and interpret narrative (as well as to have an awareness of our own bodies/emotions). I don’t think I’m unique—I truly believe that advertising and screen media (including signs, billboards, magazine glossies), make all people feel sick and unknown to themselves. But maybe people don’t want to admit it, or they’ve lost the ability to sense that discomfort within, or, or, or… Billboards with taxidermic looking white men in suits selling real estate have always been ugly and bizarre to me. But how is that possible? Really. I’ve always grown up within a consumer culture, even if I’ve ignored it, it was always there at the periphery, so why the extreme aversion? I just don’t feel very desensitized.

“Even terms like responsibility are couched in ideas congruent with ownership. Own your mistake. Own your desire. I mean, what if I don’t want to own anything? Can I rent?”

Er, I don’t know… I guess I come at this question from the opposite angle…I mean, I suspect we’re all “owned”….to a point. I’d say my mistakes and desires make ME more than I make them. I certainly don’t feel as though I “own” my mistakes or desires, though I should like to be able to admit to experiencing them. I don’t own much of commercial value, except, perhaps my laptop, which is already 4 years old, so likely not all that lucrative to sell. But if I really think about ownership in this relationship—I’d have to say that my computer owns me more than I own it, and I spend a relatively short amount of time on my computer, if I’m not using it as a type-writer (maybe 7 hours a week). On paper, I don’t own much, but it’s funny because I feel like everything in the world is mine….but not to possess or do what I’d like with, simply for me to experience as it is. And when I try to possess or control, I lose the world, or hurt people.

Ownership, property, copyright, patents…. these things wield a strange sort of power over us, it seems…undermining the freedom of the “owner,” so-to-speak…though many “owners” probably wouldn’t see it that way.

@calla: I do think it has made people sick, or at least physically and psychologically altered people. I think this is sort of clear, now. The effects of TV on children for example is pretty widely studied….though a lot of that study material is buried. But I think fluorescent lights, for example, affect people. Im very sensitive to fluorescent light. I get tired and start yawning within 15 min. I get headaches. Im not alone. Sound pollution is huge in cities. Its amazing how people adapt and suppress all these affects, but they are still there, in some form. And then there is plastic. I rant on about this, but you cannot buy a thing, not a single thing, not wrapped in plastic. And its bad for you. The rise in infertility in men, but both genders, is pretty marked. And skin cancers, etc. You know, i was at the airport the other day. And its a hostile and paranoid space. I thought, if they put out chess tables, and board games and had instructors strolling around to teach people about planes and explain the process. Free info. Free games. Pass the time and socialize. It would be a nice experience. But no…see….they must sell bags of Fritos for triple the prices and sell 8 dollar cans of coke….a cleaning solvent really…..and keep everyone scared and anxious and buying shit they dont want. Capitalism. In a nutshell.

@ Steppling,

Yes, plastic disturbs me too.

The airport observation/chess idea is really great. I was once in a hospital where they had an enormous grand piano in the lobby that played by itself. You just walk into the lobby and there is this great big piano, and the keys are moving and it is playing music but there is no one to play the keys, it is all electronic. There was something spooky about it–but not in the way you might think (i.e. because the player is invisible). It was more spooky because there are pianists out there who can’t afford to play on a piano that nice. There are pianists who will never make a livelihood from their work (as most artists don’t, not that they should make/practice art with that intention, either). I’m just trying to say that it would be amazing if institutions were creative with their public and interstitial spaces and commissioned live musicians, storytellers, whatever to ground the space, so to speak. I mean, wouldn’t that be amazing at the local hospital if you were in the hospital cafeteria and chatting with one of the cafe workers and they waved toward a fellow passing by and said, “oh, that’s so-and-so, our hospital pianist….”

Thank you, Calla, for that image of the piano in the hospital. I might write a play about it. It’s a potent image…. really sticks in my mind hauntingly