Luigi Ghirri, photography.

“…the gesture of forgiveness expresses the sovereignty of the self, which, in its full autonomy, faces off against another self. In fact, when we begin to practice forgiveness, one of the first things that often surprises us is that others do not understand. “But how could you forgive that?” we often hear. At such moments we begin to see the difference in perspectives: those third parties view reproach from a point of view (i.e. that of a legitimate right we held and are now giving up) that has little or nothing to do with the nature of forgiveness.”

Manuel Cruz

“An author’s words are deeds.”

Sigmund Freud

“The Vietnam War was for many a black and white war. People could not bear to look at it. Black and white seduces. Black and white is always something less than reality. Seduction is always something less than reality. It leaves something to be desired. You cannot see the picture, unless you fill in the gaps, unless you become complicit in the creation of the picture. Black and white draws you into the middle of the horror. Black and white is always horrific, always seductive. Colour is not like that. It is too real. It is more than reality. It leaves nothing to the imagination. It leaves nothing to be desired. One can sit quite happily in front of a colour TV, watching the mutilated bodies of children, while you eat your TV dinner. Because you are not implicated, you are not seduced, you are excluded from the horror – pushed away from it, by the excess of information.”

Donnchadh Mac an Ghoill

There is a continuing discussion to be had about art and politics, broadly speaking, but more, about how the left approaches culture and art today, 2015. I single out the left because I don’t really expect anything of the right. And, increasingly, I don’t know what those terms mean anyway. But the relationships between language, media, art & culture, and political domination is in need of recalibration. But to do all this, I want to look back a bit.

“…‘non objective’ painting, a painting without any content except color, form

and texture [that] was pretty much impermeable to political scrutiny…an

art that by its very existence denied the importance of human interaction,

of personal concern, an art that saw means as ends in themselves and

could do away with the pesky issue of social concern […] Such an entirely

self-referential art would be impossible to prosecute. Thus, it was

guaranteed to confuse and annoy the general public that, as always,

continued to favor images with an easily digestible narrative content.”

Bram Dijkstra

George Scholz

This kind of explanation has become a sort of casas belli for dismissing Abstraction in art after WW2. Russell Gullette wrote, concerning the post war climate; “What the American art world needed was an art form that would rival the modern art of Europe. Critics in America were at work to locate the artist or artists that would establish America as the new cultural, to coincide with being the economic, center of the world.” This is a sort of almost received wisdom when discussing Abstract Expressionism, and how it was all a CIA or USAID plot. And I think its probably both reductive, and distorted, and basically irrelevant; but worth talking about because it addresses several issues that are in play in what I wanted to look at here. Gullette quotes Clement Greenberg, and it’s unavoidable to not discuss the influence of Greenberg. Still this an important quote:

“…the true and most important function of the avant-garde was not to

‘experiment,’ but to find a path along which it would be possible to keep

culture moving in the midst of ideological confusion and violence.

Retiring from public altogether, the avant-garde poet or artist sought to

maintain the high level of his art by both narrowing and raising it to the

expression of an absolute in which all relativities and contradictions would

be either resolved or beside the point […] subject matter or content

becomes something to be avoided like a plague […] Content is to be

dissolved so completely into form that the work of art or literature cannot

be reduced in whole or part to anything not itself.”

Clement Greenberg

Hedda Sterne

Now, Greenberg was hugely, massively, influential. And much of what he wrote was very good, but overall I would argue against most of his positions. But more on that below. The issue I think relevant today has to do with not just modernism, or the various forces in play after WW2, but the relationship in general between art and what T.J. Clark called the ‘left academy’. Now, there is today, I would argue, a wholesale denigration and lack of urgency in discussing art at all, on both left and right. Greenberg insisted that for art to be important, at that moment historically, it must *withdraw* from society. And it is this very term that is problematic. For what does that mean? What is the opposite of *withdraw*? To engage, it seems, but what does that mean? Gullette himself rightly points out that artists remain tied to bourgeois society because, in the end, they have to eat and selling their work is the logical road to achieving that. However, speaking more metaphorically, the withdrawl seems to be implying something to do with the *content* of the art. And here we arrive at the real crux of the matter. The interpretation of artwork. And here Clark in his introduction to The Sight of Death, makes a couple very important points. He decries the left for incessantly dragging the artwork before the court of political judgement. And as Clark says, the prosecution’s position is as threadbare as the claims for what the artwork is alleged to be *saying*. The whole thing is dispiriting. For art is just not that simple. (see my posting Revisiting the New York School).

Now, of course when one is speaking of Hollywood, then it’s hard not to see the egregious right wing propaganda on display. But here we need to try to be more precise. For example; in three recent TV shows, new series, there are characters who are former MOSSAD agents now working for and with U.S. police. In all three cases they are female characters and very sexy and alluring. In two cases they are the objects of desire for the protagonist. In all three cases they are loudly loyal to the ideology of Israel, which is defacto depicted as victimized and threatened. I could site a dozen examples of anti Russian plot lines. And even now, many anti Serb story lines. OK, this is all fairly obvious. Is there a single TV series that depicts an Arab/Muslim as smart, sexy, skilled, heroic? No. The answer is no. The only times Arabs are depicted in an any way positive light is if they are servile and helpful to the U.S. military or police. That is it. Go ahead and search for an exception. Get back to me if you find it. Ok, but this is the level of mass culture, of corporate owned telecoms and studios and networks. But examine more, say, films from thirty or forty years back, or look at theatre in the U.S., or look at fiction and painting. In that sense, what Clark writes is vitally important. For it relates to what society expects from art. In the above mentioned book he is talking about two paintings of Poussin. He points out that they are reactionary, probably, and maybe even counter revolutionary. But he says we need such mirrors, such images, such artworks, to stare back at us and the image world we inhabit. We need such mirrors to really see, to see deeply, the reactionary and repressive forces at work in the world around us. And I couldn’t agree more. And this is why, it is exactly why, the cynical left, the older cynical Trotskyist left, but also just the old white left in general, can be so counter productive. They won’t engage on any level but the most brute vulgar one dimensional one regards artworks. If artist X is a reactionary, then discount his or her importance. If artist Z is a socialist, then even if he or she is dreadful, a social realist hack, we must applaud and support. It’s almost a sickness on the left.

Jeffrey Silverthorne, photography. 1982

The flip side of this is the new faux left. The white University educated young self advertised leftist. Bhaskar Sunkara is the best example, but there dozens more at Jacobin, or The Baffler, or even places like In These Times, which is just an embarrassment. This new entrepreneurial left is one which embraces mass culture, sees it as populist in the progressive sense, and seems to take the position that stuff like Mad Max, the one out now, is a feminist parable (remember Jacobin writer Eileen Jones loved The Lone Ranger). It is curious, in a way, that filmmakers, radical voices such as Pasolini, Antonioni, Fassbinder, are almost absent from discussion, today. And filmmakers like Lang or Aldrich, or Welles, are mostly just not talked about either. I rarely RARELY ever hear such references in contemporary film reviews. One would have to really dig into specialist blogs to regularly see these directors discussed. Maybe on occasion at The New Yorker or New York Review of Books you will find an article, usually pretty conservative, but also reasonably rare.

Now I know the danger of such generalizing. But I feel that Clark’s point is worth examining a bit more deeply. The rise of commodity culture in the fifties, which accelerated in the sixties and seventies, had a profound effect on both what was once called ‘high art’ and also on mass culture, on entertainment (new designation). What Jameson called ‘the imaginary museum of new global culture’ was feeding the repetitive recycling of the familiar. The ideology of ‘entertainment’ was one that sought to validate this cannibalism (per Jameson again) of earlier styles and forms.

Samuel Kootz and Harold Rosenberg, in the catalogue for their 1949 show of Abstract Expressionists, wrote:

“Dramatically personal, each painting contains

part of the artist’s self; this revelation of himself in paint being a conscious

revolt from our puritan heritage. This attitude has also led him to abandon

the curious custom of painting within the current knowledge of the

spectator, attempting instead through self-experience to enlarge the

spectator’s horizon.”

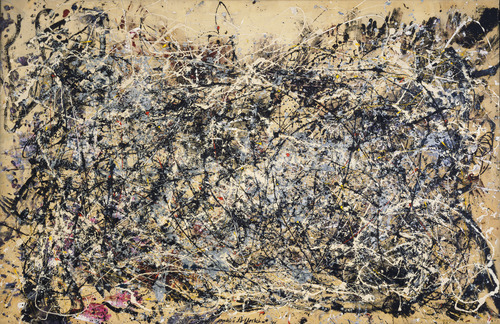

Jackson Pollock, #1, 1948

Gullette points out the influence of Existentialism at that time. But the germane issue was that this work was a counter to the cannibalizing of the familiar that was just beginning. History was being co-opted and commodified, hence the counter move was to find a pictorial strategy that wasn’t borrowing, but also one that was unfamiliar. The not familiar. The rapidity with which even this strategy was subsumed by Capital, or partially subsumed, speaks to the power of mass culture throughout the 20th century.

“The art world tends to be driven by its market, and throughout the ’50s and the ’60s it was a relatively small art world with dealers and collectors and one or two small museums. It was during that period that the most powerful and permanent American art in this century was made—from Abstract Expressionism and Pop, to Minimalism and Post-Minimalism. It was, in a real sense, a great Mediterranean moment created by 4000 heavily medicated human beings. And then in the late ’60s we had a little reformation privileging museums over dealers and universities over apprenticeship, a vast shift in the structure of cultural authority. All of a sudden rather than an art world made up of critics and dealers, collectors and artists, you have curators, you have tenured theory professors, a public funding bureaucracy—you have all of these hierarchical authority figures selling a non-hierarchical ideology in a very hierarchical way. This really destroyed the dynamic of the art world in my view, simply because like most conservative reactions to the ’60s it was aimed specifically at the destruction of sibling society—the society of contemporaries.”

Dave Hickey

Jackson Pollock, Mural on Indian Red Ground. 1950

A number of writers, from Harold Rosenberg late in his career, to Frederic Jameson, felt that an epitaph was somehow needed for Abstract Expressionism. It’s important to know what is wrong with this idea. Firstly, all image has content. The idea that abstract non figurative art is without content is wrong. But secondly, whatever tepid attempts the U.S. state dept. worked out to position Ab Ex as a symbol of American freedom in opposition to Soviet tyranny, was just rubbish anyway. Third, the later commercial success of the major Ab Ex painters does little if anything to change the experience of their work. And this is the central issue, I think. I’ve read countless articles insisting on examining the implications of not just Ab Ex, but modernism’s “failure” (there is a political version of this which likes to ask ‘why the left failed’). This is just puerile nonsense. What would success look like if Pollocks #1 1948 is now to be seen as a failure? Art is not amenable to narrative ideas of success or failure. The ‘fact’ that an artwork exists, is it’s only purpose. It’s only one. Is there a political dimension to its existence? Perhaps, but that dimension exists within a realm of subjective experience. Neither Pollock or any of the other painters in the 50s saw their practice as having any direct political link (though almost all of the New York School were leftists which is why the US state department chose them in the first place). Adorno said arts radical quotient did not reside in its opinions, but in its form. But he also said, art’s radical nature is in its purposelessness. I’ve written this before, and yet, the narrative applied from the post modern perspective is one that demands a flat-lining of difference. For Clark is right when he suggests everything slips into this vast cauldron of the Spectacle. It’s true. But its also true that Pollock (as the example here) painted real material canvases that I can still go see, and which I still marvel at, and stand rapt before. The spectacle both absorbs and cannot absorb. For it is only the spectacle. It is by its very definition something that digests and homogenizes, but ideologically. Pollock’s best work was between, say 1947, and 1950. The Blue Poles (1952) canvas probably marked the end, and his alleged panic and desperation at that time, working on that painting, signaled that he could feel the primoridial outburst of those earlier three or four years was ebbing. But it is hard to avoid the majesty of those dozen or so paintings.

“I note, that in a recent poll, one in nine Berliners said they would like the Wall back. Despite the fact that Berliners often used to complain of Mauer Angst (“Wall anxiety”), it was also recognised that the Wall made Berlin special. A kind of island away from the world. West Berliners used to speak contemptuously of the West Germans, i.e. those uncouth non-Berliners, and felt sure they could spot a West German on the streets just by their uncouth gait. Today, Berliners lovingly maintain icons of the DDR, such as the Trabant and Ampelmännchen–the DDR’s beloved traffic green man. One can take DDR tours, and even stay in a hotel that is fitted out to give a full 1980s DDR experience. Above all, people miss the feeling of living in a real community, where what they thought and said mattered–even if only to the Stasi. I’m being facetious here, but there is a certain comfort in believing that somebody cares–which is probably why so many people in the West today actually feel a certain relief when they hear that the NSA is recording their phone calls and tracing their movements.”

Donnchadh Mac an Ghoill

Robin Lambert, photography.

I am the last person to suggest that the ascension of marketing, of a society based on Bernays’ ideas and a media which is now hyper consolidated and hegemonic, is not profoundly shaping Western consciousness. I write of little else, finally. But it has struck me of late how degraded is the idea of culture in its totality, today. Which leads to the second topic I want to touch on, and it’s related to the first. Donnchadh Mac an Ghoill, who writes mostly in Irish, is a journalist and thinker worth searching out. His point above is related to Hickey’s point, which is that community has been largely erased in the U.S. and much of Europe. The white centeredness of U.S. culture, even on the left, is striking. You find white male academics rebuking a young black woman, on Twitter. You see and you hear the patronizing tone of older white (faux) leftists. And it has created a conflicted dynamic, because the older white academics are sometimes right. They might have been exactly right in their analysis in some particular case, but the failure to check their own sense of entitlement is highly problematic. Even when they are right, they are wrong. The relationship that I want to look at more closely, though, is how this entitlement affects the reading of art, and also more broadly, of culture.

“It is important to remember that language itself is a moral medium, almost all uses of language convey value. This is one reason why we are almost always morally active. Life is soaked in the moral, literature is soaked in the moral.”

Iris Murdoch (in conversation with Bryan McGhee)

Urs Fischer

The rise of irony, which seems to be getting discussed a lot lately, has infected discourse and culture. It has affected art, certainly. So, when one goes back to look at Pollock, say, the validity of his work, and his *success*, if you want, lies in the enormity of his sincerity. And the issue here has to do with language, in one sense. The ways in which we narrative ourselves to ourselves and to the world. Snark degrades, both those using it and those answering it. One of the problems with snarky white commentators, today, is that there is no appropriate answer other than silence. Irony fits, it seems, quite well with a consumer culture, and more, with this idea of *entertainment*. Morality is learned in and with language. Morality is developed in the same way language is learned and developed, but also in culture. Culture is described and narrated, and artworks are expressing some kind of narrative. Alice Crary argues that learning language encodes a certain morality. What she calls a “moral outlook”. Additionally, I would argue that learning cultural and artistic history, and taste, develops a discrimination that is imbued with the moral. The endless diet of ironic and sarcastic work teaches a certain moral outlook, an outlook that diminishes ideas of cooperation and community. The internalizing of that tone, from early childhood, especially coupled to the deadness and cold of the screen, is producing a generation of neural impaired-emotional Zombies . My position has been that aesthetic resistance is linked to what linguistic acquisition brings with it in the form of attention, and a growth of evaluative thinking. A steady diet of TV kitsch narratives, texting, tweeting, and more, of a securitized urban landscape of distrust and suspicion, cannot be producing warm inclusive contactual humans.

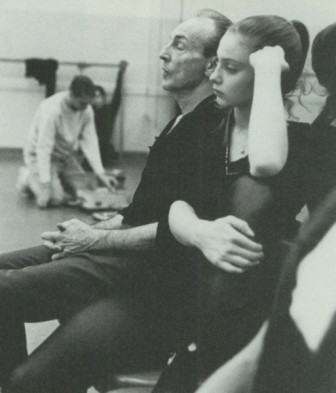

White supremacism, the white centered story, is predicated on exclusion. The kind of practice that yields a master calligrapher, or a Suzanne Farrell, or Ballanchine for that matter, or Coltrane, or Pollock has something to do with a humility in the face of the material world. That is the story. That is always one of the stories. Here is the world, and it is mysterious and infinite. And I will work and practice and practice and practice to make just a small mark on it, even if just transitory.

Balanchine and Farrell. 1960s.

But why does one value such practice, such personal sacrifice, in a sense? This question actually brings us closer to heart of all this. I suspect that great artists are always in some sense casualties. This is, I know, derided often as a manufactured construct of heroism or the cliche of the tragic artist. But, commitment means sacrifice, on some level, and great artists are never going to be widely embraced by a mass public, not today anyway. The idea of belonging, that notion of being recognized, is crucial to mental health, and more, it is the foundation for a vision of social change. Never before has a society so emphasized the acceptability of isolation and alienation.

“I like the idea that art or creative expression can serve as a form of

political resistance, that the individual is capable of converting their own existential

concern into a statement capable of reasserting to the bourgeoisie that, “[…] the

underside of culture is blood, torture, death, and terror.” (Jameson)…”

Russell Gullette

Songs From the 2nd Floor (2000), Roy Andersson, dr.

Now, aesthetics today, in contemporary culture, always seem to return us to this idea of *the uncanny*. It feels inescapable. I could easily include the idea of allegory, too, because they are closely linked. So, this idea of practice, of creating, of imagination, is also always a story of the psychoanalytical and of the uncanny.

“The beginning is already haunted.”

Nicholas Royale

The reason, or one of them, perhaps the primary one, that the uncanny has such traction right now is that it is an idea that lies in opposition to scientific certainty. It is that tiny ghost image, that gnawing doubt about the equation that might be the source of cosmic disruption. One of the reasons I think the Hadron Collidor has purchase on the imagination is because it is almost ALL uncanniness. It is an experiement ABOUT uncanny, about that which fleetingly appears, or not, on the edges of existence. Wittgenstein approached this through language, that lost in the interstices of grammar was a kind of lost unease. Ariane Mnouchkine once said, in conversation, that nothing is really natural. Looking out your window for a minute and seeing your dog playing in the yard is normal. Is natural. But if you look out that window for three hours, it becomes unnatural. There is a sense running through all discussions of the uncanny of homesickness. The theatre is probably the art form must attuned to the uncanny. And I suspect the uncanny is closely aligned with anxiety. And I believe contemporary society, Capitalist society anyway, is awash in anxiety. Now, it is possible, I think, that the societies of the West, today, given a spike in this very particular new sense of anxiety, are finding a particular fascination with uncanniness.

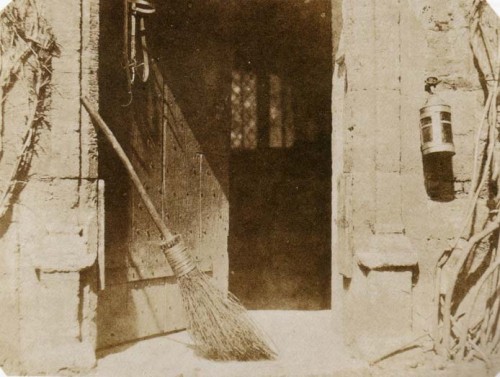

William Fox Talbot, photography, 1843

Roy Andersson’s Songs From the 2nd Floor(2000), is almost entirely a film depicting the uncanny. It is a film that on the one hand was a critique of post industrial malaise in Swedish society. But the dream like quality of its formalist imagery depicts an exaggerated ordinariness. In terms of art I think there is something in 20th century modernist expression that intuitively gravitated toward that which seemed to question notions of certainty. The scientific method relied on a belief in certainty, and that which expressed doubt became very attractive. Now, is there is a connection between evaluative thinking, with language, and the acquisition of language by the young, and this moral outlook that links to community and what Hickey called ‘sibling society’, and with a society of domination that was increasingly producing an aggravated anxiety in people?

But before answering that, there are questions about certainty on an experiential level. If an engineer designs a bridge, and does the requisite calculations, and sends the blueprints to builders who follow the specs, and at the end of that, there is a bridge over the river, then a certain validation of the scientific method has taken place. Those using the bridge, are evidencing trust that the bridge won’t collapse and fall into the river. If you get cancer, but you feel fine, but you go take an MRI exam and the doctor tells you, here, look…see? That dark smudge there, that’s a tumor, well, most of us have to trust this doctor. After all he graduated from medical school, and on and on and on. Trust in institutions. Trust in those priests of medicine. Those quasi Gods of the hospital. So, most of us would go ahead and allow them to enter our body with laser scalpels, and rid us of this smudge. There is gratitude, because now that doctor says we won’t die. But it is all remote from us, on a phenomenological level. There is gratitude, but there is also an oppressive sense of having no control. Science dictates daily life. Specialists know more about everything we do than we do. Unless we are a specialist ourselves. But even then, we must trust other specialists. There is a kind of psychic burden to daily life in post industrial society.

Kano Sansetsu. “Old Plum”, sliding door panels (fusuma) 1646.

Now the uncanny is experienced throughout all these encounters with science and authority. With specialists and with the constant unthinking (usually) trust we just tacitly hand over. Underneath that is a subtle anxiety. The society of control creates both physical limits and prohibitions (don’t walk on the grass) and psychological ones (Excuse me Sir, can you please open your bag). The psychological apparatus of control can be also be invisible. CCTV, NSA wire taps, etc. Someone is watching. Someone is reading, or at least storing away what we wrote or said. And everywhere there are restrictions, bureaucracy, and policing. Nicholas Royal describes the uncanny as that which cannot be pinned down or controlled. There is no mastery with the uncanny. Nor can it be intentionally manufactured. It is outside our technology. It is anti-technological in fact, it cannot me measured or weighed. Now, there is also, as Helen Cixous points out, something performative about the uncanny. And, curiously perhaps, the uncanny can be both an addition, or a subtraction to any given state. If we enter a grotto, an already loaded semi mythical environment and we reach the center or end of this space, and nothing is there…that can be uncanny. If we arrive and a strange albino rat scurries away into the shadows…that is probably not uncanny. It might be strange, or startling, or odd, but that is different. The uncanny is an experience of something we cannot identify. But it is more than just that. It is our narration of this experience. Much like how Freud discussed our descriptions of dreams. It isn’t the dream, it’s how we describe it. How we narrate it.

Sunil Shah, photography.

I suspect that the uncanny, what we label as uncanny, has changed over time. But additionally, the uncanny, as we understand it, is linked to modernity. There is a reason to try and understand more clearly what is meant by the uncanny. There is something significant, and perhaps moral, too, encoded in the uncanny effect. In pre modern society there was no uncanny. For the uncanny is both an oppositional force to modernity and domination, as well as being always a *meta uncanny*. Tzvetan Todorov suggested that the uncanny always takes place in a narrative ‘about’ the uncanny. Here it resembles the *tragic* in the sense that it is performative, and an act of revelation, and not a diagnostic category. But there is another aspect to this which has to do with the appearance of doubling and boundaries and repetition. One of the things that is disruptive about Pollock, is the idea of edges. The painting is not framed. So it is with narrative, I think. Now, when I say the uncanny is a product of modernity, I think I need to be clearer. The ghost is Hamlet is something close to the uncanny, but it’s not. And why not? Because the ghost is a convention we understand, it has an intellectual shape. The uncanny experience is that which escapes the controls under which we live. The uncanny as criminal, then. Transgressive in some respect, perhaps. The experience is fugitive, certainly.

Paolo Verzone, photography. / Agence VU/ Cadets of the Hellenic Naval Academy. 2009

The Industrial Revolution probably altered human life more than we think. By the turn of the 20th century, the implications were being seen and felt acutely, in various ways, across the planet. The uncanny is the return of something repressed, it is the repetition compulsion surfacing in a domain of narrative, image, memory, and journey. In that sense, the uncanny is also always about ghosts of the dead. The voices that didn’t get heard properly. The ghosts take various forms. The unspeaking ghost, even culture specific apparitions and folk beliefs (Chupacabra, et al) are expressions born out of the same psychoanalytic stew. The sense of Freud’s *death drive* is that it is the modern post Industrial revolution version of the same obsessive concretizing of inexplicable experience of death, loss, absence that Pharaonic Egypt ritualized. Ghosts are escaping from tombs or crypts somewhere. The contemporary kitsch Hollywood expression of monsters is the exact opposite of its original psychic purpose.

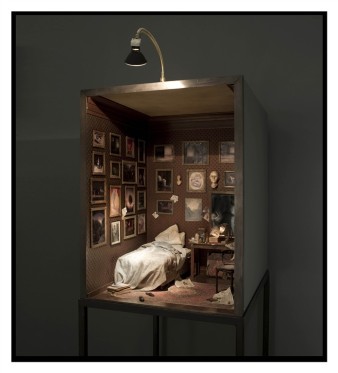

Charles Matton

There is much more to say, which will form part two of this posting, next time. The Death Drive is a very contested notion. It is the ‘across the tracks’ territory for psychoanalysis. It is, however, I think unfairly impugned. For the ideas of a moral outlook being encoded in art, in culture, and in the communal, the discourse of the communal, are also bound together by desire and desire’s rhythm section is always the Death Drive. The ritual pathway — our narrative sense, our narrative and moral outlook, our evaluative development; it is all ambivalent, and it all must both embrace and recoil from our recognition of mortality. Great art always acknowledges the death drive, in my opinion. Pollock’s art did, acutely, and perhaps it was his intuitive closeness to death that makes that great four year period so affecting. Melville, Kafka, Rembrandt, Goya, or Bach, and Beethoven. The Beethoven of Missa Solemnis, the Bartok of the late quartets. Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. All great work. Pinter’s major plays, Genet’s, and Handke. Somewhere in all of these works lurks that battle of angels. The village narrative in which the Chupacabra appears and kills a goat, is much the same village where ghosts appear. But more on that in the next post.

I am glad you quoted Murdoch here. I have been reading a large collection of her essays over the past couple months on art, literature, philosophy and ethics (written mostly in the 50s and 60s); she had a strong voice, bold ideas, and rigorous intellect which I feel is rare these days. I will quote her again in reference to a statement you made….

Steppling:

“So, when one goes back to look at Pollock, say, the validity of his work, and his *success*, if you want, lies in the enormity of his sincerity. And the issue here has to do with language, in one sense”

“Tyrants always fear art because tyrants want to mystify while art tends to clarify. The good artist is a vehicle of truth……..Any dictator attempts to degrade the language because this is a way to mystify.” –Iris Murdoch

Steppling:

“Adorno said arts radical quotient did not reside in its opinions, but in its form. But he also said, art’s radical nature is in its purposelessness. I’ve written this before, and yet, the narrative applied from the post modern perspective is one that demands a flat-lining of difference.”

I have another quote by Murdoch here that I think relates to Adorno’s “form” as “art’s radical nature.” This passage of Murdoch’s (quoted below) also speaks to abstract painting and, I think, to that arrogant notion people have in regards to ‘non-objective’ paintings when they state, “I could have painted that!” What I find compelling about this passage, is the way Murdoch traces the connection between the very unique, individual artist and that artist’s role as a truth teller of the world or the “other” (whether that true depiction of the world be of colour, light, space, people)–and that this honest depiction of “otherness” in the artwork is perceived Through the Form–a form which both reveals and creates its own “standards” of truth which the viewer must apprehend in order to appreciate the revelations. If we, as viewers, can apprehend the standards of truth designed through the Form the artwork takes–and thereby evaluate its truthfulness from this understanding of form, I think, we have here a striking example of empathy–of non-egoistic empathy…..a forgetting of the self (which Murdoch also describes in reference to Shakespeare in another of her essays). Both the artist must do this, and the audience must do this “forgetting.” But through this sort of “forgetting,” I would argue, is a more radical remembering, or expanding, or re-connecting. (I also think this has to do with the MRI machine, but won’t go there now).

And of course this is radical….especially today. Empathy, feeling, caring, noticing things are all dangerous and threatening to the capitalist, consumerist status quo….

Here is the quote….

Iris Murdoch:

“[T]he paradox of art is that the work itself may, as it were, have to invent the methods by which we verify it, by which we test it for truth, to erect its own interior standards of truthfulness. And one might think in this connection about abstract painting which is so often taken as a paradigm of what is happening to literature now, [a] paradigm often used in formalist criticism because here the notion of the object dissolving into something else is most evident. One sees in paintings by Mondrian, for instance, the way in which what in a first painting in a series looks like a tree becomes something much more like a lot of squares or oblongs in the final version. Good abstract paintings are not just idle daubs or scrawls, forms wandering round at random in spaces, they are somehow about light and colour and space, and I think that this is something that he abstract painter is very conscious of, he is not in a state of total freedom, he is relating himself to something else and his paintings exist for us in a world where we normally take colours to be parts of objects. The painter and the writer confront these curious problems about a reality which is alien and at the same time something which they are bestowing meaning upon, which they are related to in this curious internal relation. Formalism draws out attention to the extent to which we are responsible for what we see. Yet, the otherness of nature is a more important part of the image. We bestow significance but we also constantly test it and we incorporate the tests, the tests of truth, in the work itself. This is very evident in a novel where the reader rightly expects, however odd the work may be, some kind of moral aesthetic sense of direction, some indication of HOW (emphasis mine) to read the relation, or apparent lack of relation, to the ordinary world” (Murdoch, 1978).