Cantemir Hausi

“The art world is divided into those people who look at Raphael as if it’s graffiti, and those who look at graffiti as if it’s Raphael, and I prefer the latter.”

Dave Hickey

“This period led me into personal contact with Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, Max Horkheimer, Siegfried Kracauer, and Theodor W. Adorno, and the writings of Georg Lukács and Herbert Marcuse. Strange though it may sound I do not hesitate to say that the new development of Marxist thought which these people represent evolved as the theoretical and ideological superstructure of the revolution that never happened. In it re-echo the thunder of the gun battle for the Marstall in Berlin at Christmas 1918, and the shooting of the Spartacus rising in the following winter.”

Alfred Sohn-Rethel

“Everything that has been and is no longer we call historical.”

Alois Riegl

Contemporary fields of art are all marked by the ascendance of profit as an art form itself, one that supercedes the actual art object. This is true in fiction and journalism, it’s true in music and it’s true, even, in philosophy (or *theory*, the more du jour word). Making correct career decisions (one’s that make you money) is the one single broad stroke of validation that this society provides. This is coupled to the rise of a new career left — the cavalry charge of which is led by Bhaskar Sunkara, but he is hardly alone. There is the desperate clutching at mainstream gigs, those now occupied by people like Natasha Lennard and Laurie Penny (who are creepily and eerily alike in appearance) and those who carry water for them. Sunkara’s recent red bashing piece at The Nation (http://www.thenation.com/article/198529/red-any-other-name) is a typical example of this new trend, which also incorporates the VICE like prose stylings of late-Gonzo. It is so obviously a toadying gesture to the establishment that one is surprised anyone, literally, views this stuff as oppositional in any way to the status quo. Its pro capitalist, anti communist, and it, on perhaps an even more insidious level, aesthetically reproduces that watered down affable faux intimate tone that is employed in a slightly altered way by the likes of VICE and Slate et al. It is additionally, if we take Sunkara’s piece, an example of that inevitable reductive revisionism so popular at places like The Nation. But no matter, because anything that suggests commercial viability is going to be embraced and applauded. Its the model first established by Hollywood. Advertising “Surprise Summer Hit”. Nobody wants to be on the outside of that.

Canaletto; ‘The Arch of Septimius’. 1742

This is what I was trying to point toward in an earlier post; the insider wink at the audience, or readership. *We* know *you* know that this is for you. The kool kids clique. Nobody wants to eat lunch alone. And this notion of mass approval as a virtue is reinforced constantly by Hollywood product. It is The Breakfast Club, version nine thousand six. The Sunkara piece is simply the *theory* version of Harold Ramis or Chris Crowe or John Hughes. For that is the sensibility in play, and it is interesting in terms of both the whiteness of those cultural signposts, and the alteration of race as a subject now subsumed in the faux left of this under cover red baiting one sees in Sunkara (read his back handed obit to Pete Seeger), but in Zizek, too, of course, and in Penny or Lennerd or the laughable Molly Crapapple ( Jennifer Caban).

The name change is savvy branding. Right?

This sensibility matters only to the degree it has infected left discourse over the last ten years. When the NYTimes does puff pieces on you, something is wrong. What does it mean to self identify as a *leftist* or (cough) *neo marxist* when you clearly are not against Capitalism? When you are, in fact, a proto Capitalist. What does that mean? Which side are you on, and all that. Know the enemy. Well, the enemy is the likes of Sunkara or anyone else pimping for the establishment. Period. And when one is openly and intentionally seen as expert in marketing, what are the implications if you are also, in theory, a leftist of some sort?

Here is a quote from the NYTimes piece on Sunkara and Jacobin (his magazine)

“Not that Mr. Sunkara, who is also the magazine’s publisher, dismisses the value of pop-culture come-ons (the new issue includes a radical analysis of the Onion’s online reality-television satire “Sex House”) or good visuals. The sleek design by Remeike Forbes, an M.F.A. student from the Rhode Island School of Design who e-mailed Mr. Sunkara out of the blue in 2011 offering to design a Jacobin T-shirt, has been essential to getting people to take the magazine seriously, he said.”

Define what ‘taken seriously’ means in this context.

Sixteen Candles (1984). John Hughes, dr.

I have written before that the Hollywood films of the 80s, and perhaps the late 70s, too, were creating a sensibility that was in accord with Reagan era revisionism. The Reagan era corrective to Viet Nam malaise was the way the project was seen, I think. Ramis and Hughes and Landis and SNL was all of a piece. It was primarily white, and gave off the message of *middle class*, which was really the selling of a fantasy realm of suburbia that never existed. Speilberg, of course, was the other branch of this formatting of a new sensibility. And it had huge influence on art and culture, as well of course as politics, and of course they all overlapped.

Sunkara, not surprisingly, has ties to VICE, and wrote for them.

VICE is the ideological child of Reagan era re-branding, the co-opting of Hunter S. Thompson, the incorporating of Tom Wolfe, and it was always driven by anti counter culture mentality. The regrouping of the U.S. government, in terms of image control, was in overdrive after the fall of Saigon. Now, this is all fairly obvious, I think, but the more insidious effects, at least in terms of culture and art, has been the ascension of an art market controlled by rich collectors, and gallery collaboration, and museum ceding of authority — all under the guise of a convenient post structuralist grammar that enabled the rise of *irony* to gain full traction as the subject position for the more affluent University educated young. If *camp* was the elite appreciation of junk, then this migrated (by way of post structuralist theory)into the dismissing of genuinely critical thought. Marx became Neo Marx, Freud was so outdated, and thinkers like Adorno, or Bloch, or Horkeheimer were dismissed as old fashioned. The technique here was always to appropriate aspects of these thinkers, and then to repurpose their thought for the opposite meaning. Under cover of acceptable positions such as feminism, or anti racism, or diversity, the very thinkers and artists who were, in fact, anti racist and feminist, and altogether radical (communist and Marxist) were labeled as racist or misogynist or totalitarian. Then carefully the most domesticated of the intellectual outside were vetted and let *in*. There were exceptions to these trends, certainly. Lacan rescued (as did writers like Russell Jacoby) the radical aspects of Freud, and expanded on his most radical ideas. But in the case of Lacan, he was quickly absorbed by writers like Zizek who both turned him into his opposite, and if that didn’t work, simply misread him. Cultural and intellectual table turning has taken place on all fronts from the late 70s through today.

Glenys Barton

Now today, there is another aspect of colonizing and shaping consciousness, and that is the securitizing of reality. Jack Kahn writes…

“For those white subjects who commit acts of spectacular violence, the national gaze penetrates past the skin—explaining violence through a molecularized discourse of the diseased body. Power must search for inscriptions of deviancy on surfaces other than the whiteness of their skin, imbricating their neural embodiment with pathology—rendering disability as a risk to the health of the nation. For example, by circulating the medical diagnoses of neurodivergent school shooters within the media, the nation comes to know the violent [white] perpetrators as diseased bodies, as sick citizens who “fall through the cracks” of the medical apparatus meant to anticipate the development of their disordered embodiments. Unable to attribute violence to infection by racialized outsiders, the media attaches the “autism epidemic” to the phenomenon of school shootings, narrating a crisis regarding the cancerous emergence of dangerous pathogenicity from within the social body.”

Kahn’s essay touches on the role such stigmatizing plays in the field of art and culture, too. There are two things going on here, one is the medicalized stigmatizing of anyone not fitting into very narrow definitions of normal, as well as at large a society ever more infantilized and ever more reductive in how it processes image and, more significantly, narrative. The world of screen experience begins to take on qualities associated with autism. While simultaneously those designated as autistic are employed for the purposes of ratcheting up fear and justifying increases in surveillance and control techniques.

Sammy Baloji, photography, mixed media.

“Within this conceptual apparatus, the racialized school shooter becomes a result of his or her culture, while those who engender the death of white students become emblems of their extraordinary neural difference. In this way, the machinery which make the vitality of the neuron radiant with danger do not supplant racial hierarchies, but further cement them within the fabric of the nation by rendering certain deaths as (extra)ordinary. Neuronationalism attaches itself to already structured social exclusions in order to manage fear among affluent citizens within the nation from pathogenic threats within the social body, a form of risk-management that responds to a perceived insecurity from the aleatory emergence of violence. The purview of national security therefore extends to the surface of the brain in an effort to secure hierarchies already structured by state violence.”

Jack Kahn

The society at large, increasingly infantile, rarely question these definitions. The culture today reinforces all of this with remarkable speed, turning out movie versions of school shootings, or (of course) endless terror attacks, and always with a backdrop that demonizes any nation refusing to go along with U.S. directives on trade or the economy. The public is disciplined to think in very reductive terms lest they be pathologized as *outside the ordinary*.

Peeping Tom (1960), Michael Powell, dr.

It is easy, I think, to discard certain ideas, and authenticity is one, under the aegis of this new kool theory that finds it’s way into most *leftist* publications today. For authenticity is, in fact, a form of resistance culturally. It is that which is not ersatz. However, it is easy to see its manipulated expression as quite the opposite. In a world where everything is a brand, the ideas become reformulated and repurposed, and in the end rebranded. This is the age of disappearance. The search for transcendence, however, is not negated because the spiritual usually fails. Most everything today fails. Most everything evaporates. But then, in a convoluted way that is the message of that 80s project of mystification; where class and inequality were disappeared. Where irony and snark were used in the service of ridiculing sincerity and authenticity. Partly this is the Zizek rhetoric at work; racism is really the new anti racism, misogyny is the new feminism, and so forth. Imperialism is trivialized, and it is easy enough to do that because the suffering entailed is far away and non-white. The childish cultural products of today, from Marvel Comix movies to Lena Dunham are intentional signifiers of the *ordinary*. They take place in a carefully monitored region of white ordinary — the borders of which are as surveilled as any U.S. consulate. Gotham City is ordinary, it is the re-accesorized version of an older fantasy of New York. History is reduced to very carefully managed epochs that feed the master narrative of euro centric white domination as ‘normal’. There never was a high school anywhere in the known universe that was like those in John Hughes’ films, nor a suburbia like that in Spielberg or his imitators. Hollywood as it exists now is increasingly in the creative hands of white men who grew up with enormous privilege and whose tastes run to the middle brow, but a very immature middle brow.

The Hustler (1961), Robert Rossen, dr.

Everything from Boyhood to Breaking Bad, or House of Cards are the legatees of that shift in 80s popular culture that followed on U.S. State Department and Pentagon PR machinery, on Wall Street and the Milton Freidman/Ayn Rand vision of white superiority, and the innate virtue of wealth. The reaction to civil rights, to Viet Nam and the anti war movement, to Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. and to radical social theory, from Laing to Gestalt, and from May 68. A cursory glance at film in the 70s and late 60s is pretty instructive. Two films from 1960 serve as intriguing markers; one was Peeping Tom, directed by Michael Powell, and the other was Psycho, directed by Alfred Hitchcock. In both cases there is a dark psychoanalytic exhumation of the human unconscious. Both are essentially pessimistic and unforgiving. And both were prescient visions of a certain simulacra led life and the derailment of sensuous experience.

It is not too hard to look at any number of films from the U.S. during the 60s and 70s. Everything from Point Blank (67) to Who’ll Stop the Rain (78) which marked the far end of a certain kind of Hollywood filmmaking. But Two Lane Blacktop (71), and The Hustler (61) are only two more that were unapologetically pessimistic, and socially critical. The front edges of this cultural shift, though, could be seen already in the 70s, when Freidkin’s Sorcerer flopped and Star Wars set the template for a new infantilism. Close Encounters of the Third Kind (77) and Deer Hunter were both in their way a kind of recalculation of how to present the contemporary psyche. Viet Nam was now about the suffering of the American soldier, and not his guilt or remorse (let alone the suffering of the Vietnamese), and the new nostalgia personified by Speilberg (for an imaginary past) was coupled to an infantile fantasy about outer space. The Hustler was perhaps the last truly tragic American film. It was Rossen’s guilt that drove the dark vision of human relations, after he named names at HUAC. While himself a member of the Communist Party, his fear of never working again weakened him in his third appearance before the Committee. He never really made anything else of any importance and died three years later. It is interesting that Rossen, who grew up poor and Jewish in NYC had previously made almost only films with working class themes. In any event, looking at TV, the shift came even earlier. The corporate takeover and model for hour long drama took hold, really, in the mid 60s. Probably due to the influence of Jack Webb. The point here though is to survey the contemporary landscape of opposition. The new marketing from the inauthentic left is “how did the left fuck up so bad”? Which happens to be the slug line for a new magazine called Salvage. Firstly, that very statement is so rife with bad faith and distortion as to be risible. What might that even mean? Who is being referred to here? This might be a good place to return to the fashion in thinkers and theory today.

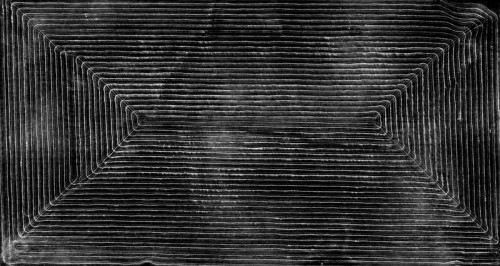

Erich Reusch

“Ideology in class society serves the interests of the class that dominates. In our society, that ideology is held up as the only possible set of attributes and beliefs, and we are all more or less impelled to adopt them, and to identify ourselves as members of the ‘middle class’, a mystified category based on vague and shifting criteria, including income levels, social status, and identification, that substitutes for an image of the dominant class and its real foundations of social power.”

Martha Rosler

Today, culture no longer is approached seriously. Mostly, it is an accessory to consumption, and self branding. Rosler amusingly points out …“Those who aspire to move upward socially are led to develop superfluous skills — gourmet cooking, small boat navigation — whose real significance is extragant, well rationalized consumerism and the cultivation of the self.” Often such fetishized leisure time pursuits ape aspects of the working class (buying industrial restaurant stoves for the home kitchen etc) The fashion for such stuff also links to the Speilbergian version of imaginary nostalgia. This is the faux *authentic*.

“Time and again in interviews and questionnaires one is asked what one has for a hobby. Whenever the illustrated newspapers report one of those matadors of the culture industry -whereby talking about such people in turn constitutes one of the chief activities of the culture industry- then only seldom do the papers miss the opportunity to tell something more or less homely about the hobbies of the people in question. I am startled by the question whenever I meet with it. I have no hobby. Not that I’m a workaholic who wouldn’t know how to do anything else but get down to business and do what has to be done. But rather I take the activities with which I occupy myself beyond the bounds of my official profession, without exception, so seriously that I would be shocked by the idea that they had anything to do with hobbies -that is, activities I’m mindlessly infatuated with only in order to kill time- if my experiences had not toughened me against manifestations of barbarism that have become self-evident and acceptable…”

Adorno

Frank Stella

The model perpetuated in those 80s films is one that is still a mainstay of Madison Avenue. Leisure time is *family time*, and when it’s not, the non family time is sold as an acceptable guilty pleasure. Usually for the man in the family. In a sense, Bhaskar Sunkara is the Sam Walton of leftist publishing. Now, aesthetics is folded into political discussions, and in complex ways. And it is at this point that the contemporary model for what constitutes history is worth examining. Art today is consumed largely as a leisure time activity. Hence the feeling of mimicking a perceived labor activity of the past. Experiencing art for the majority of affluent educated Americans is not unlike choosing which industrial oven to buy for their remodeled kitchen. The ascension of pop in the 1960s was a crucial step in eliminating both the unconscious and in aestheticizing the conformity of daily drudgery. Campbell soup cans contained crappy cheap soup, but no matter, it became art. The rich didn’t buy Campbell tomato soup, trust me, but they did buy Warhol’s paintings.

Pop art, additionally, positioned the artist as collector or scavenger of images, as an archivist for the everyday. Except there is no *everyday* , nor is there any object that does not have an ideological meaning, which is of course mediated by context. Whatever value one puts on pop art, the idea of the *artist* changed. Conceptual art changed it further. A small recouping of dialectical tensions was mounted by some minimalists; the work of Donald Judd for example, or Anne Truitt, Richard Serra, or Tony Smith was almost an attempt to imbue the flat expressionless face of pop with a subtext reaching for the sublime.

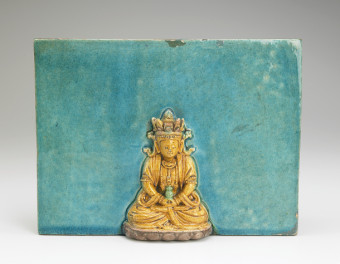

Amitabha Buddha, 16th century, Ming Dynasty.

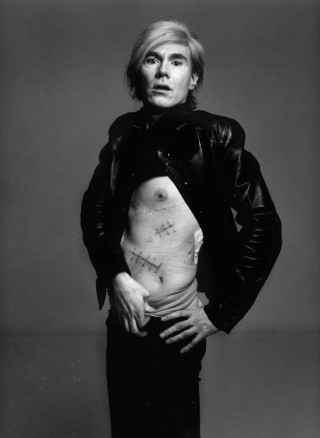

Richard Avedon, photography. “Andy Warhol”.

“[T]he mannerism of Canaletto … gives the buildings neither their architectural beauty nor their ancestral dignity, for there is no texture of stone nor character of age in Canaletto’s touch; which is invariably a violent, black, sharp, ruled penmanlike line, as far removed from the grace of nature as from her faintness and transparency.”

Ruskin

Canaletto was the pop version of Piranesi, in a sense. The Dutch painter Luca Carlevarijs drew memorabilia for wealthy tourists touring the continent, and Canaletto often copied his figures. What were essentially cartoons, but tricked out with a highbrow exaggerated detail. There is, it should be said, a wonderful kind of light in Canaletto, but usually his work is analysed in terms of architecture. But more, perhaps, he is remembered for a fascination with ruins and pleasing his wealthy clients. And this returns to the topic of history. I am hard pressed to think of many contemporary painters who evoke historical memory. And if they do it is usually a cheap or sentimental polemic. On the other hand, the *idea* of ruins are reproduced today in the most trendy interior designs. Retaining stripped brick or cement provides that juxtaposition with superfluous luxury of which the wealthy are so fond.

Ayaz Kala, Uzbekistan (ancient Korezm) 4th century BC (photo courtesy of Hugh Bergin).

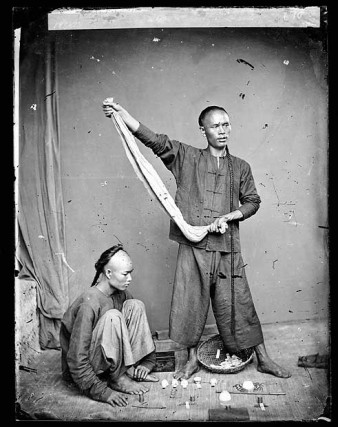

John Thomson, photographer. Manchu 1860’s.

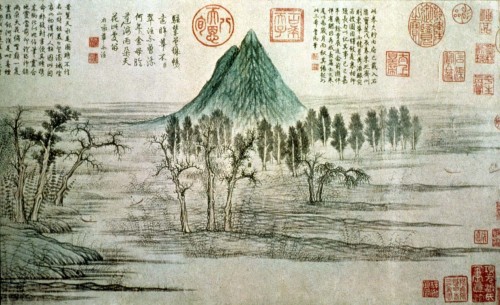

The early exemplars of Chinese painting were not directly creating narratives. They were, however, looking at the tensions of transience and continuity, of solidity and ephemeral, and they were looking at implications of destruction and survival. So in another sense, they were narrating, for mimesis is always a narrative at some level. Still, nothing specific was indicated. If it were Hollywood, the D girl would be asking for back story. In contemporary Western art the inheritance of Pop, but more of course from marketing and PR, from a sense of the Puritanical that never left the U.S. population, there are no such tensions. Or, rather, there are, but they come about vis rather different strategies.

Zhou Meng Fu. 1296. Yuan Dynasty.

Artists such as Toba Khedoori, or Marco Tirelli, or R.H. Quaytman perhaps,…there is an emotional linkage that can only be activated by memory, and memory is about the historical. Jeff Koons is not historical. Nor was Warhol. The point is that here one runs into this discussion about authenticity, again. If I read, say, Rachel Kushner, or Zadie Smith, just as semi random examples, I simply have no emotional tension because I do not believe those writers. What specifically is it that is missing? Or is anything missing? It certainly feels, to me, a good deal is missing. If one reads George Eliot, or even Patricia Highsmith, I am aware of that quality of intelligence, it is clear and radiant (terms used for Chinese painters in the 13th century). But it’s true. The selfless vision. In film, of course, things are much muddier, more mediated. The ruins so popular right now among urban explorers, or hipster speelunkers, are appealing for obvious reasons, I think. There is something triggered internally at the sight of waste and failure, it reminds us of disappointment and our own frailties. At the very least there is a superficial melancholy. But to lament the past, to arrive at huaigu requires more. Is it simply the lens through which ruins are sent, the medium of the artist. It is hard to have conversations today about artists without feeling defensive about the word. The anti art message that denigrated the cult of genius (as it should, mind you, but more on that in a second) took along with that all crafts and skill and simply surrendered to the idea that technology could do everything better anyway, and faster. The entire fabric of such discourse is firmly planted in bourgeois society. Tens of millions in the global south don’t give a shit about Jeff Koons. That however is not quite the point. The autonomy Adorno spoke of, the sense of the purposelessness of art being its radical expression, is under post modern theorizing a kind of target for snark. The so often but still obvious problem today in the art world is that the working class is invisible and mute.

Nadav Kander, photography. Yangtze River (“The Long River” 2011)

There is also the fact that art continues, in the guise of entertainment, leisure time activity, or hobby, to grow ever more stupid, more homogeneous and more childlike. Children have no past. Adults who remain children have no past. The past has no indicators. The false authentic, which Adorno was quick to recognize in Stravinsky’s parodic primal ostentation, is today actually increasingly hard to find. The culture that cant even produce FAKE authenticity, let alone anything approximating the real. But, I can hear people say, what does authenticity mean? What constitutes the authentic. The obvious answer is that there is no answer. Not to those questions. However, as Robert Hullot-Kentor puts it:

“Aesthetics becomes key in Adorno’s thinking, as throughout mid-century philosophy, because aesthetic experience condenses in itself the temporal dimension that is otherwise held out of mind in the mechanical mastery of space.”

That’s a very dense sentence. But art, for Adorno, meant the unconscious transcription of historical suffering. That is really a key feature. If art is not doing that, then it is complicit in the ongoing colonizing of the subjectivity, or perhaps more accurately the occupation of subjectivity. Art we experience as valuable is art that knows more about the world than we do, and more about ourselves. This is what authenticity is, in one sense. The snark reflex today is so breathtakingly acute that often entire days can pass without a single conversation that is spoken with any sincerity. The collective of the western bourgeoisie has forgotten very simple human exchanges. The immaterial corner of labor consumes leisure time (well, it turns it into another form of work) and it allows both anonymity and eliminates privacy simultaneously. The authentic is that which is not serving the society’s masters. There is a deep psychological construct today that is involved in rationalizing service to the ruling class. And as Freud knew, such constructs erupt in irrationality and aggression in other places. Now I quoted Adorno recently to the effect that the stamp of authenticity is *possibility*. What this practically means is that art promises something (Adorno and Horkheimer both wrote on this) and fails to honor that promise. But not from want of trying. This relates to the disenchantment of the world. The authentic then is that which admits failure, submits, and continues on. It is the Beckett world view in a sense. But to be more precise; art, looked at from a certain position, is impossible. Recognizing that means the artist no longer creates work meant to succeed. And if the artist is not succeeding, then he or she is examining the impossible with dispassion and care, with attention. With sincerity. For success is never sincere.

Marco Tirelli

I want to return at the end to those figures in Canaletto. And compare them to Vermeer’s figures in View on Delft (1660). Never mind the Vermeer is now too famous and reproduced to really appreciate, but compare the figures. First, of course, the Vermeer is associated with Proust because of the scene in A la recherche du temps perdu where the critic dies in front of the painting. Second, Vermeer is a vastly superior artist to Canaletto. But it is the evoking of something authentic that the Vermeer holds us, our attention. The light on the roofs, the dark clouds, and it is so easy to imagine that day, what it felt like. And so your gaze turns to the figures. There is such an acute poignancy in those dark robed figures. Why? The answer is that something in that painting knows something very deep and elusive and it is buried in us, too. That is authenticity, I think. Canaletto was a high level hack. He was John Hughes, or David Fincher. He was Lichtenstein. He was Stan Lee. But Vermeer is indeed transcribing something of historical suffering. And that light, on the roofs, on the water, is what we have missed in our lives. It doesn’t matter who we are, we have missed it. We were not there that day. And those figures, the two women, the men in black. Who were they? How did we not meet them? The narrative comes to us in some necessary manner, it is inextricable and certain. And what John Ruskin said of Canaletto is true. There is a violence that accompanies the hack’s work. It is subtle at times, or not. It takes our time without returning anything. Vermeer knows that in a sense, we *are* there that day. Here is the border of the spiritual in art. When the artwork returns our gaze. And when the artwork knows something that we do not know.

Johannes Vermeer, ‘View on Delft’. 1660.

The fascist today cannot bear to look too hard. They must ridicule sincerity, authenticity, honor. Because fascism is about only winning, about domination. And that is a form of blindness.

“The autonomy Adorno spoke of, the sense of the purposelessness of art being its radical expression, is under post modern theorizing a kind of target for snark. The so often but still obvious problem today in the art world is that the working class is invisible and mute.”

As someone who chose a working class profession after a fairly formal education, I occasionally try to bridge the gap of snark and radical expression. This seems to me a near impossible task. For without some education under a teacher or two with integrity, and then self-education, we are in the hands of the spectacle, as most reading this post know. Even when a person is receptive, and some new understanding occurs, they are right back in to the system of polarization, fear, and are re indoctrinated. As you state in this essay John, contemporary art is fully monetized and its values are dictated from high. If I understand you correctly, you say the real value in visual art is historical, independent of these systems and interests that have co-opted it. It seems to me that the values that penetrate its conception and production make this accomplishment very rare, I’ll grant you Theda Khedoori and a few others. I think that the majority of institutionally accepted work that is fully complicit usually swallows these few exceptions. Most can only glimpse this history by going to the institutions that exhibit it, and most cannot really separate the Currin from the Khedoori. Or maybe they can, but what do they do with this brief insight? I can see a case for art that is conceived as only opposition, some graffiti does this, and surely some working in obscurity. Maybe revamped education, taking direction from Friere and Giroux can build a foundation for another path, but we are talking a whole new generation and a long time. I guess the big question is, can art itself be the education and resistance in any meaningful way, or is it at best set up as foundation and history for the next economic system?

@ David G. Very troubling questions. I think that all we can do is to fight and resist to the best of our abilities, and hope that we can find some people to do it in solidarity. To remind each other of our humanity. Fact is, as long as there remains an unbroken lineage, a tradition that remains, no matter how besieged it is, there will still be hope.

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

— T.S. Eliot, “Four Quartets: East Coker”

“there is no repetition in selfmanifestation”

“the horizon of possibility is the real / the imagination”

“yes / no”

ibn al-‘arabi

In the given context I would warmly recommend to consider the above cited – considering the possiblitiy of opposing with sheer perception (his time 12th century syria…) theologians and rationalists clearing away the possibility of an individual imagination… i guess what was called in the 12th century theological or philosophical establishment could be seen nowadays as uncritical believe in civilisation in a sense of technology, positivism and established nihilism or the religion of nonsense arts … in a post post post world /

but dont catch the wrong translation… /

however great article / thanks