Justin Fantl, photography.

“Glacial Wash”.

“Every photograph which exists to perpetuate something becomes its grave and tombstone.”

Richard Hennessy

“Integrity is not only a moral condition, but a pictorial task.”

Michael Fried

“Memory is not an instrument for surveying the past but its theater. It is the medium of past experience, just as the earth is the medium in which dead cities lie buried.”

Walter Benjamin

A discussion of abstraction in art is usually something one has with in-laws, or weird Uncles during the Holidays. It is usually a simple argument about how abstract art isn’t really art, and how anyone could do it, and how modern art in general is junk. Rarely are there serious discussions about abstraction as a history. But it’s a good discussion to have because it forces an articulation of concepts and judgments normally glossed over.

The most convenient starting point (and trust me, this leads somewhere, or at least I hope it does) is Matisse. This is sort of conventional wisdom; Matisse was sort of moving in the direction of decorative and away from impressionism. What is meant by decorative is worth a whole posting, honestly, but for now, the work Matisse did around 1906 was distinctly decorative.

Clement Greenberg wrote, in 1973,

“The word *decorative* is no longer used as freely as it once was in finding fault with works of pictorial art. Too much of the best art of our time was criticized, when first seen, for being too “decorative”. Matisse’s art in particular was criticized for that and it continued to be criticized for that. But if the word is now largely a discredited word, at least in its pejorative sense, it’s Matisse’s doing more than anyone else’s.”

John Gerrard. “Oil Stick Work” installation.

By the 1940s, and especially in his late masterpiece The Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, Matisse was not exactly even painting as it was normally concieved. The Church, which I have always loved, and on a personal level I think it incorporates something of a dream many have in youth, an eternal spring, or early summer. For it is not just the light, the white and bright blues, but it is the careless air, the nonchalance and almost insolence of his design that is so seductive — but the church was a work of decoration primarily. The nonchalance is, though, warm, the insolence sweet. It is irresistible, and of course location is irresistible as well. But, Matisse influenced Abstract Expressionism, and minimalism, both. I think Morris Louis must have felt very close the Chapelle, for example, but clearly Rothko did too, and later, Rothko would paint several triptychs for his own Church in Houston. Anyway, the decorative works of Matisse, and then also of the late Monet (a great influence on Barnett Newman) painting was inching into pure decoration, but also not. It was not just decoration, and the reasons for it not being *just* decoration are what is crucial here.

The Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence . Design and painting by Henri Matisse. 1948

If Adorno was right about society being ‘in’ the artwork, then that entails something of history. Jameson partly (largely?) defined post modernism a schizophrenic inability to separate the past from the present, and hence also an inability to posit the future, or *a* future. The schizophrenic part, of course, was Deleuze’s influence, but what was really being looked at was a loss of historical truth. A loss of history. And I think history is always both social, planetary, and personal. The societal and the personal are reflective of each other to some degree. What I choose to call the planetary is more the secret history of the world. The world of corporate culture, of mass electronic screen focused culture is one in which, I think, something regressive is taking place. I dont believe it is built into the technology, but I’m not sure. Certainly, however, the ways and the means of production, the forces of production, have stunted the audience’s ability to experience awe and wonder (for lack of better words).

Morris Louis

Now, I find that this has a political dimension (or several) that is seen in how many in the West fail to process the idea of, as an example, the torture report. This is too closely linked to mass culture. And the real agony of being chained to a wall on tip toe, while having already broken bones in your foot — this does not register because in kitsch TV people can get kicked and punched and hit with a baseball bat and next scene appear only slightly bruised. One punch to the face, in reality, can break bones that never heal. A fractured supra orbital bone, or infraorbital margin, has happened to someone I know, or just a busted jaw, can damage nerves that never heal. Can have long term repercussions, such as headaches, loss of balance and other inner ear problems, nasal inflammation, and impaired vision. But one rarely sees that in TV. People are supernatural in their ability to recover. So torture has no resonance. We had Bush, a President who chuckled when Tammy Faye Tucker begged for her life, and there is Hillary Clinton, cackling at the idea of assassination. The idea of violence and torture has no resonance. So, I think this inability to experience art, and by extension nature, is additionally a loss of the mythic register of life. A failure to imagine the rapture of secrecy or the hidden. Walter Benjamin said Kafka was the last storyteller. This had to do with those levels of secrecy and hiddeness that narrative, good narrative, operates on. Again, the conditioning to expect the trivial stops the search for expanded meanings. The post modern mass culture obviously knows the word *history*, and people know what it means, but there is no sense of historical truth penetrating daily life today. People, the general modern public is addicted to the *now*. The present is emphasized because the present is when you shop, and also because the present can limit notions of future and past. I suspect the future is now more a risk assessment column in a spread sheet, its predictive, but its not a dream, Utopian, or even sensed in its relationship to the past. And this is where, in this light, that one can discuss artworks, and abstraction.

Alexander Archipenko, 1913

Adorno believed artworks were the unconscious writing of history. That through their detachment from the everyday, they sustained an autonomy and an isolation that resisted the mass forces of trivializing. This is why it is never easy to accommodate populism and aesthetic idealism. But as Hullot-Kenter writes; “…Adorno details the immediate object of aversion from which modern art and Schoenberg’s music withdrew. There he writes that just as abstract art was defensively motivated by its opposition to photography — the mechanical artwork — Schoenberg’s music developed in ‘antithesis to the extension of the culture industry into music’s own domain’.” As Hullot Kenter points out about Schoenberg, here was music you would never hear in an elevator. Now, it is worth noting that I don’t think its possible to discuss abstraction without also discussing photography. And I want to digress just a bit here, for I look at a lot of photography books, at a lot of portfolios, and over the years I’ve come to the conclusion that separating fine art photography from journalistic is impossible. Of course there are the far ends of each, but there is the larger meeting area where they overlap. This month Ive looked at maybe sixty photographers in some depth. Of those there are maybe, MAYBE five who are special. There were mostly new photographers. There is just something ineffable and very delicate in those five. There were good photographers I saw, professional, with great technique and knowledge and care, but that additionally rare and, I think, hidden or secret quest wasn’t there. Awoiska van der Molen has that nearly religious quality. Perhaps it is partly found more in landscape photography, I dont know. Sugimoto is my favorite photographer, who is living anyway. It is a different sort of hidden you find in Sugimoto. It is more linked to his mimetic re-looking — and that’s an odd sounding phrase and idea — but if one looks at Sugimoto’s landscapes, or seascapes, it is hard not to feel the probing eye of the photographer, but at the same time the quality of almost monastarial quiet and respect. Van der Molen, a much younger artist, is also quiet. She waits. She waits and hardly breathes and eventually things emerge from out of the dark. Jason Fantl’s color photographs of remote landscapes are surgically examining the materials, the feel the sense of space and time. For that is the history embedded in artworks. In photography there must be a sense of history, and almost always expressed by that awareness for time passing.

Simon Harsent, photography.

Simon Harsent’s book of photographs of icebergs is majestic and disquieting. The subject matter itself carries with it a foreboding and melancholy. There have been several photo essays on the arctic and icebergs, but none as good as Harsent’s. Kevin Cooley’s photos of Iceland and the arctic also carry that strange wounded beauty and it is perhaps our awareness of climate change that enhances this feeling of the temporal. Of places one naturally equates with the eternal, with time distanced from the present, but one now fragile and suddenly so impermanent. Joel Tettamnti, too, has some remarkable photographs of Greenland. But this is a particular anxiety being expressed, as climate change and industrial polluting of nature imposes an additional layer of meaning.

But there is another aspect of modern photography, and it has to do with how photography agitates that feeling in all of us of having missed something. This can be seen in the anxiety of people checking their e-mails every five minutes, of people looking around at trendy restaurants to see if anyone notable is there, too. But it is in photography in an acute way. In painting, as Richard Hennessy wrote, details do not break down. In photography they do. And here is yet another meeting point in this discussion between representational painting and abstraction. Hennessy’s remarkable essay from 1979 (Artforum, Vol.19, no.9) suggests that the allure of painting resides primarily in its touch, the fact that it is hand made. In a photograph one can compose but not construct (per Hennessy). The real issue though, raised in this essay, and which I have touched on before, is the decline in taste. That the educated classes today learn of art in the classroom. Today, more, on the laptop. The sense of scale experienced in Abstract Expressionism, for example, is lost. It is hard not to approach art as design if all you know of it is what you glean from the screen of a laptop. This problem is compounded by the ascension of advertising. The non stop production of image, photograph and film and TV. But I disagree with Hennessy on a several points, but with caution. The difficulty has to do with looking at the body of work from, say, Durer, or Goya, or Velasquez, and wonder at the impossibility of such expansiveness today. Or, even in literature, though this gets trickier. But the impossibility of tragedy today would seem a directly related topic. Now Hennessy uses the example of Rodin’s sculpture at the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia. There were (are?) photographs of some of the sculpture occupying the same room. The comparing and contrasting of the photos with the actual sculpture lands, finally, on the fact of the materiality of the sculpture. As Hennessy says, “It is here.” And that presence, that undeniable fact raises questions about the *not hereness* of screen culture.

Misha de Ridder, photography.

Today, there is a sense of, indeed, schizophrenic space. Only it is, in urban areas, a militarized schizophrenia. And additionally, perhaps it is being processed increasingly in ways that mirror the autistic’s processing of place. But this also intensifies the class divisions in Western society. The access to such contemplation resides in the educated white audience. Here I will mention Irish artist John Gerrard’s Oil Stick installation. http://simonprestongallery.com/?gallery_exhibition=oil-stick-work

There are striking images in this piece, no question. But the *concept* is more than a little problematic. First off, the catalogue bothers to note that the farm worker is a ‘Mexican American’, for reasons unknown. So here again we have an elite class extracting labor, paid or not, without really addressing the implications of this contract. In any event, the labor is in the interests of extracting image which is to be shown at various galleries for an audience with time and money to view it. There is something perturbing in this. It is part of the class segragation at work again. The artist who hires interns or assistants to help with his or her project seem rarely to grasp for whom their work is being created. But more, to return to Durer or Rembrandt or whoever, there is a question of comprehensiveness in play. It is hard to imagine Durer writing out a conceptual explanation to accompany his painting or etching. As if somehow the materiality of the *thing* wasn’t enough, there was the fact that it would take *time* for the piece to be complete, and etc etc etc. Now photography is part of this question. The reason I value the photographers I value is that their work seems to approach this question from another direction. Contra Hennessy, there is something uniquely linked in the best photography to our sense of the irretrievable past. All photos suggest a temporal desire, a searching for the past, even if only momentarily past. That is what a photograph is, memento from the immediate past in a sense. Mass culture siphons off this desire to create kitsch anecdotes, vacation postcards and this has the effect of soothing the anxiety of amnesia. In this sense in the subjective is organized the nonidentity of the universal and particular (per Adorno) and it is given expression not as domination but as freedom, but this organization is what mass culture destroys, or is always working to tear down. So, all the manufactured images of mass commodity culture work at eroding the transformative potential of autonomous art. Or, in other words, the forces of capitalist production are always at work to prevent that subjective organization that authentic art creates. One of the negative influences of mass culture has been its granting permission for a fake populism to be embraced by left and right alike, for different reasons, but also for the same reason — it is simply easier.

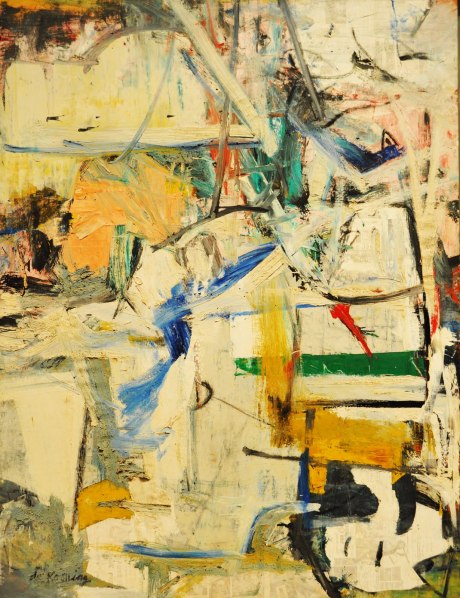

Willem De Kooning

Karl Lowith noted that in the 18th Brumaire des Louis Bonaparte, Marx says the bourgeoise had passions without truth, and their truths without passion. There is a sense that he saw their world as one of constant repetitive borrowing and discarding, and the only development was the growth in tension that came out of each cycle of the same. *Indecision* was the defining element. I was struck this week with just far down the road of infantilizing and dullness today’s culture has traveled the last sixty years. A friend I know, a playwright, and a quite good one, wrote me to describe the process of application for this fellowship in theatre. She didn’t get it, there were a couple thousand entries. The finalists all had MFA’s, three of the four were white, all went to expensive universities and all had been workshopped at either Yale, Brown, Colombia or Harvard. Nothing of any quality has come out of this system for twenty five years. Nothing. This new professional class of artist is, like John Gerrard (who at least has, I believe, talent) looking at the world from the vantage point of their superiority. Kierkegaard saw the same culture Marx saw, but through his own Christian filter. And he clocked what he saw as Europe’s spiritual decline. Adorno’s first published work was on Kierkegaard. He wrote “…there is only an isolated subjectivity, surrounded by a dark otherness.” Another of Marx’s insights is that we are essentially acting not as ourselves, but as agents of ourselves. Everyone is manipulated or coerced by history, both collective and individual. One does something, say, pay a gas bill. That is coerced; you are tasked with the reality of the gas bill. Today, the accumulation of empty activity has grown, in fact has grown so far as to be almost the totality of waking life, and hence it has become the culture as well. If art and culture were once antagonists to social coercion, today art is the replica of social coercion. The most experimental *art* today actually IS social coercion. This is what Marina Abramovic has perfected as her brand. Of course there are artists making great work, and experimenting, but they largely remain on the margins. I don’t think ever before has there been such a clear divide between commercial entertainments, regardless if labeled as something else, and serious work.

Adorno in his early writing on Kierkegaard, but also again at the end of his life in his lecture notes, emphasized that these social necessities are in a sense what forms the borders or boundaries of what is called the ‘individual’. We are shaped, deep in our psyche, by the trauma of entering the world, and by this coercive socialization process. So, that *indecision* Marx noted was echoed in “Either/Or”. The spiritual decline was, in crude terms, exemplified by a gulf between ourselves as agents of ourselves, and ourselves as a subjectivity hidden and even secret.

Giorgio di Noto, photography/video. From Tunesia 2011, “The Arab Revolt”.

“The sphere of psychology in which we imagine that we are ourselves is also the sphere in which in a certain, obscure sense we are furthest from being ourselves. This is because we are performed by that being-for-others to the very core of our being.”

Adorno

Lecture 8, History and Freedom, 1964

The coercion of socialization, that performing of the role of yourself, which is necessitated by material conditions, is what captures the last corner of autonomous existence in the human. It is also the historical process at work. And a forgetting of history, a denial of this coercion, eliminates any chance for transformative consciousness. Put another way, today, mass culture, the hegemony of giant corporate electronic screen harvesting of attention is the last incursion of the last assault on being human, or more precisely, on the human capacity to mature into adulthood, and establish the preconditions for genuine awareness, of spiritual growth. Everything in this assault is advertised for its humaness, as help, and asks for conciliatory submission in the individual. The individual as audience. Mass audience. One is instructed to see this role as mass audience as actually the zenith of individuality — the public is told that this is what they ‘want’. So the last remaining corner of old growth consciousness is clear cut. And this is, honestly, for me, what the mass public psyche feels like today. The resistance to this is coming from those most exploited by these forces. And there is much to feel encouraged about in the protests this week coming from both the Michael Brown and Eric Garner murders. But nobody escapes this psychic intrusion.

Reich’s term *emotional plague* (of which I was reminded in the last comment thread) is amazingly pertinent today. I knew an old Reichian, someone who had studied with a man who was an early student of Reichs’. I find myself referring back to our discussions probably more than anyone else in my life that I can remember. And often the idea of sexual fascism came up, of the emotional plague. Americans today are astoundingly angry. And this is part of what one can track in Hollywood film and TV. It is a nastiness, a pettiness, a selfish snarky bitter resentment that surfaces under guise of one abstraction or another. Adorno, in those great late lectures in 1964 and 65, writing about the colonizing of consciousness, said: “We are not dealing with arbitrary subjective processes that can be avoided as long as you have a modicum of insight, self confidence and critical spirit. A necessity rules here and you can count yourself lucky if you can keep your head above water long enough to recognize it and give it a name. But no none should imagine that he is immune to it or that a fortunate intellectual disposition can make him independent of such mechanisms.”

Kano Sansetu. Early 17th century, painted screens.

Adorno was speaking to his University students. I always read his lectures and am surprised at the enormous affection he has for these students, and warmth, and it so flies in the face of the popular conception of him. But then of course this is the time of the emotional plague. Adorno added in that lecture, as an afterthought to his class, for his topic was not social psychology, that if humans today were to be able to really grasp the extent to which they are imprinted by the Universal (the untruth that is the whole) they would likely not be able to bear it. Their self esteem and confidence being so severely crushed, would not be resilient enough to recover.

Today, the striving for profit among the ownership class, and the striving for survival among the working poor, yield the deformities of character Reich spoke of, and really that Freud wrote of as well. The peculiarity of 21st bourgeois character formation resides, I think, in this compulsion to both be meaningful and important historically — this deep identification with the Universal — and the refusal to grow up. The adult children of the West are, today, increasingly strident, hysterical, bitter, maladaptive to any procedure that includes cooperation and sharing. The infantile selfishness of American society is making it the most unpleasant place to live perhaps in the world. And that is not really an exaggeration.

Humberto Rivas, photography. ‘Barcelona 1980’.

The coddled privilege of white people is true enough, but this same educated class suffers the deepest psychological impairments amid their relative comfort. This is what sublimation really entails, the sacrifice of a certain inwardness. Today, there has perhaps never been so many echos, the constant reiteration of some trope, some meme, some assumption or position that is granted acceptance because of clever advertising or propaganda. I cannot believe in the history of the world that any society has so had it’s citizens parrot each other to this degree. Once something is in the cycle, it must be iterated several billion times, in cyber space, at home, in public, anywhere until the perfect crystalized but empty symbol remains. But to bring this back to the history of abstraction.

That mass public taste today tends toward the infantile, the question of abstraction might seem beside the point. And perhaps in one way it is. The infantilized U.S. viewer, or audience, gravitates toward the cuddly, the fluffy, the inane. Telly Tubby art in a sense. Jeff Koons is more or less an example of this. In narrative, the current abysmal “Showtime” series The Affair (now predictably nominated for awards)is writing that, in its sentimentality and distance from reality, serves as a teddy bear might to a child. Comforting, real but not real. One holds it close and sees in it something wonderful about my family and friends, or in the case of The Affair, and not the teddy bear, about my class; it is quintessentially middle brow, but worse, it is this pretend gravitas that is, in reality, just the talismanic teddy bear of white superiority. Abstraction does have a history, and it is in that historical self awareness, that is, the artworks self awareness (in a sense) that the working out of the ultimate implications of what came before take place. Another way to say this, to look at Matisse is to examine the implications of his technique and touch. Of course it is easy to see why Matisse meant so much to DeKooning. And then why Monet meant so much to Newman. It is not simply technique though, it is social history too. The world is reconstructed emotionally by the artists touch. For Ruskin, a history of abstraction might be hard to imagine. For John Berger it might be far easier. And the same for Robert Hughes, and Donald Kuspit. If Arshile Gorky was working out his childhood exile he was doing it by way of Kandinsky. Still, for all the first generation Ab Ex painters there was certainly an awareness of a history of abstraction. And part of that was to reduce or eliminate references, quotes. I never believed this meant that so called ‘action painting’ was ever about action, OR surface. But it was about the renewal of the spiritual. By the time of the Chapelle, Matisse was no longer searching for technical answers, he was a sort of Zen priest who surveys the world, acceptingly, resignedly, but always sensually. Matisse was among the last of the genuinely unrepressed artists of the century. At least in his work. Summer ended, I think, at Vence.

Alia Malley, photography. ‘Los Angeles’.

The cultural climate today is one that would rather laugh at the Whitney Biennial winners than to experience them. Of course, the Whitney winners are only there to BE sneered at. This isn’t serious work, this is marketing. It is the extraction of attention from a public increasingly hostile to culture and art in general. Without mock controversy there is fuck all to say about the crap usually put up at Whitney Biennial. If public opinion is not ridiculing the work, the Biennial has failed miserably. Those fellowships in theatre, as rigged as the Ferguson Grand Jury, that parse out monies to elite students at rich universities, working with *star* professors of theatre, are no different from any corrupt illegitimate institution. But the idea of Abstraction in painting is not the removal of a story, it is the expansion of it. The very existence of work that defies conventional historical quotes, or that conveniently tells the viewer the *concept* behind the work, is work whose lack of purpose is actually its autonomous unreconciled tension, the non identical Universal and particular. It is also work, at its best, that is a corrective to the emotional plague. It is the anti Puritan relfex.

A final note here. I wrote a piece that will appear at Truthout soon. It was about urban space, freeways, and in particular about Los Angeles freeways. This in light of the protests, and it touched on class divisions marked by this traffic arteries. As I was researching it I came across some photos by Alia Malley. I recognized immediately that they were of LA. I even knew pretty close where in LA. But what I liked was that this was an El Lay that I know, and its an LA that is never seen in Hollywood film or TV. It is the evocative spaces of the far east of the county, Irwindale to Fontana, and Duarte and beyond. These are the empty industrial spaces of a very neglected lumpen Los Angeles. I was born in St Joseph’s hospital in Burbank. I grew up in Los Angeles, in Hollywood actually. The space of Los Angeles, the hills, the deserts, the freeways are ingrained in my vision, and now being away, in the near arctic Norway, it is very powerful to see and so instantly access that imprint on me that are these images.

Alia Malley, photography. ‘Los Angeles’.

We never forget the space of our birth. Of childhood. It always is retained in a secret location in our memory, sometimes not accessible even to ourselves. But this is always a conflicted memory trace, for these memories also are part of the mechanism that chains us to this unsolvable unreconciled idea of life, and is closely attached to mimesis. In one sense, it is directly linked. For *I* am *that*. The curve of those hills, right there. This is, however, an identification premised on a reductive psychology. But this is that coercion, for I am most myself in those photos, and I am also least myself. I am become most vulnerable at this moment to the ideology that created this entire model of experience. The past is what is always being broken with, if you read art critics and historians. What they mean usually is this is art that is NOT breaking with the past. For if it were, we would not be calling it art. The nostalgia for home is a profound myth for the 20th century, and the 21st. Forced migration, the exile, those who never return home. There is no more horrific image in contemporary life than Israeli settlers wantonly cutting down Palestinian olive trees. This they understood, the occupier knows this is how to destroy memory. The looting of the Baghdad museum was another example of removing even the possibility for memory, and then, logically, for culture. In the United States today, there is little memory. There is jingoism and the somnambulant screen culture of a constant now. The somnambulant texting as he sleep walks, while the state continues its practices of waterboarding and rectal feeding. Genuine art is a refuge (Adorno) of mimesis, and this refuge has unmistakable monastarial connotations, but this is almost an inner symbolic enactment (or vice versa) of some Thai and Japanese monasteries in which monks sat in rows facing each other, or sat in rows with their backs to the ‘other’. Either/Or.

Awoiska Van der Molen, photography.

Abstract art is not a Rorschach test. Nor gestalt. And this touches on the ways in which the artist works out his own logic of mimesis. Until mass culture today is eventually stripped down to allow a painstaking excavation of the ideology of Empire.

I find in U.S. society today a strange paradox as it relates to both culture and politics. The snide infantile narcissistic petulance co-exists with a sort of pseudo positivist need to agree, a compulsion for agreement. The result is this parroting of cliched agreement undercut with an equally hysterical need to be special, to hold special opinions, to own these opinions like one owns a new Mercedes or new Nike trainers. The approach to artworks tilts far toward a positioning of agreement, and this feels like the blowback of the unreconciled. Nobody escapes, but it would be a sign of transformative change to hear critical ideas that were not about ‘winning’ or owning. That were more about simply a kind of distrust. Western society needs far more distrust in the same way it needs a new ability to listen. The white population certainly needs to listen. To shut up, and listen to people of color, and to the poor. Listen to those that the media label losers. Just be quiet and listen. Distrust winning in all forms, but mostly, just listen.

“The coercion of socialization, that performing of the role of yourself, which is necessitated by material conditions, is what captures the last corner of autonomous existence in the human. It is also the historical process at work. And a forgetting of history, a denial of this coercion, eliminates any chance for transformative consciousness. Put another way, today, mass culture, the hegemony of giant corporate electronic screen harvesting of attention is the last incursion of the last assault on being human, or more precisely, on the human capacity to mature into adulthood, and establish the preconditions for genuine awareness, of spiritual growth.”

—

“The world is reconstructed emotionally by the artists touch. […] Still, for all the first generation Ab Ex painters there was certainly an awareness of a history of abstraction. And part of that was to reduce or eliminate references, quotes. I never believed this meant that so called ‘action painting’ was ever about action, OR surface. But it was about the renewal of the spiritual. By the time of the Chapelle, Matisse was no longer searching for technical answers, he was a sort of Zen priest who surveys the world, acceptingly, resignedly, but always sensually.”

—

I’ve picked these quotes because they touch on a topic (or set of topics) I’ve been turning round in my brain for months now trying to get straight. This idea of maturity – what it means to be mature – in life, in art. What is it to be self-aware? To be self-aware and refuse to lessen the burden of it through irony or obfuscation, but to stare one’s self (both then and now) full in the face. How do you even do that if, as Adorno says above, when we imagine ourselves to be most like ourselves, that is when we are most distant from ourselves. There is so much of this around today, the extension of self-consciousness only as far as an awareness of how one is supposed to be. Which of course is not any kind of self-consciousness at all – practically the opposite in fact; it is a purely social consciousness. A reflection.

I’ve been working on-and-off on a Feldman essay (with much talk of Rothko too) and this is what it has circled in on, the links between abstraction, expression and maturity. And, of course, spirituality. The sense that, by focusing purely on the sound – rather than any impression of what the sound represents – one is least capable of “authentic self expression”, because, if done honestly, it can have nothing to do with your idea of you, only your feeling for the material you’re working. But it is precisely here, at the point of complete self-negation, that one finds a remarkable sensuality, a sensitivity to the world and to the human, that is positively religious.

This is, I feel, close to the secret (“The spiritual decline was, in crude terms, exemplified by a gulf between ourselves as agents of ourselves, and ourselves as a subjectivity hidden and even secret”) you talk about here, particularly as it relates to home and childhood:

“We never forget the space of our birth. Of childhood. It always is retained in a secret location in our memory, sometimes not accessible even to ourselves. But this is always a conflicted memory trace, for these memories also are part of the mechanism that chains us to this unsolvable unreconciled idea of life, and is closely attached to mimesis. In one sense, it is directly linked. For *I* am *that*. The curve of those hills, right there. […] The past is what is always being broken with, if you read art critics and historians. What they mean usually is this is art that is NOT breaking with the past. For if it were, we would not be calling it art.”

Feldman’s work breaks with the past, for it is not nostalgic. It is full of memory, or mimesis, but never nostalgia. In refusing to trivialise the past, or escape into it, Feldman wasn’t so much “remembering the future” – not pointing a way forward – but remembering a time outside of time. A time when time stood still. A time when there is no “forward”, there only is – no matter what. Very Zen, though he’d hardly approve of me saying it.

There’s a particular pertinence to this piece in the UK – coming in a week in which the Guardian’s declared photography to be not an art, and a cafe selling £3plus bowls of cereal opened in one of the poorest areas of London (too massive queues, exclusively adult).

The cafe, course, is called The Cereal Killer and is decorated with alternated images of children’s mascots and famous pop culture mass murderers.because how could it ever not?

Something else came to mind too https://www.vfiles.com/shop/products/8844

Thanks for those comments. I read about Cereal Killer. Its such self parody that its not. And it does speak to this post. The idea of photography not being an art goes back to the 70s. Hennessy’s essay is very perceptive, really sharp, but he was pretty much saying something similar. And I think this has all sorts of implications. But at the front of those is this idea that one cant have art until you have *great* artists. That somehow only as an extension of personality does art become relevant. Its very regressive but it no doubt connects to the eroding idea the bourgeoisie has of *identity*. But there is more to say on that.

My comment is just general. Your blog is a steady light in the swirling chaos and noise of the time we are living in. I write, and I know that I have been shaped on some deeper level by your thought since I first came to the blog, by your thoughts on the problems faced by art in this moment of cultural malaise bound up in geo political imperialism. I discuss this blog with a friend and I know he feels the same way about it. Long may you continue to share your writing. Thank you John.

Darragh McCausland

Karla Faye Tucker?