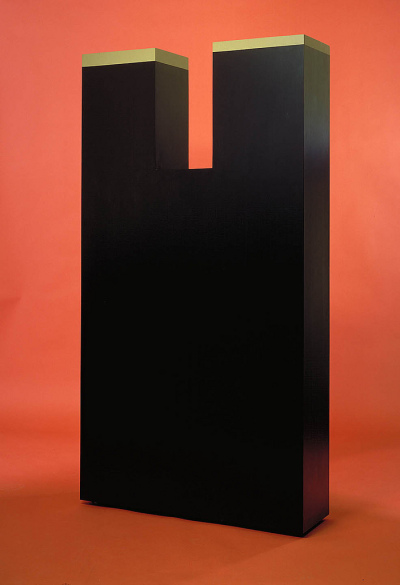

Anne Truitt

“In the late ’60s, Guy Debord—who was a situationalist—he looked again at the work of Edward Bernays, and saw that now what we called the media was starting to be joined by governments and by financial banking systems. And he called it the “integrated spectacle.” So we’re all living in this completely false reality that doesn’t really exist. The thing that’s so funny is that we’ve become the mouthpiece of this consumersism.”

Penny Arcade

“The sage, holding onto the left half of the tally

does not demand payment from others;

the person with potency {de} takes charge of the tally;

the person without potency looks to collecting on it.”

Lao Tzu

“On the other side there are doubts about whether the reality of such features of our world as consciousness, intentionality, meaning, purpose, thought, and value can be accommodated in a universe consisting at the most basic level only of physical facts — facts, however sophisticated, of the kind revealed by the physical sciences.”

Thomas Nagel

There was a moment, about half way through David Fincher’s new film Gone Girl when I started to ask myself why Fincher had chosen this material. Perhaps its an homage of sorts to Vertigo, but the question remained for me throughout. Nothing Fincher did suggested a desire to reach beyond the clever or derivitive. That sense of intellectual pillage seems to fascinate Fincher. One could argue, well, that’s what genre partly is, always. Maybe, maybe this is just borrowing from Brian DePalma, and Hitchcock, and from himself even, and maybe in a sense that is just post modern sampling. But I happened to watch Vertigo not so long ago, and there is something in that film that is linked to deeper questions of memory, and conformity, of how we rewrite our own histories. In Gone Girl there is none of that, there isnt much more than the working out of a puzzle. But this is not, probably, entirely the fault of Fincher. Or rather, he is an artist trained in another era, a director borrowing image and story from another world. An imaginary world.

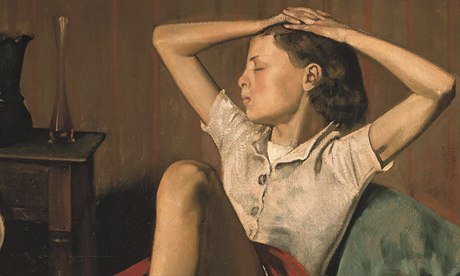

Balthus

Jacques Ranciere, in a new book on cinema, suggests three branches of approach to film: theory, politics, and art. The cinephile’s love of cinema is something I remember, and on a personal level was something I learned from my old departed friend Terry Ork. I think everyone probably had a conflicted relationship with Ork, but I have never learned as much from any single person as I did from him. The cinephile’s passion for film was linked to the idea of mise en scene, something very hard to define, but as Ranciere put it, something that inevitably led to a kind of wisdom. Mise en scene was that quality of establishing a relation to the world, that was expressed in that ineffable frame, and sequence. Certain directors seemed to have an innate ability to create a film vocabulary that allowed for a deeper engagement with the world, and with one’s own memory. Take Vertigo, for example; a film that has haunted and disrupted audiences since it was made. But why? Seeing it again I found myself just as transfixed as I had been the first time I saw it, and the ten times in between. There is something quite independent of the narrative (it seems) that triggers an emotional reverie. In some peculiar way, that I hope to transcribe here a bit, it has is a strange mythic rhythm and sense of image that seduces the viewer. It is a secret cinema.

“Cinema is also an ideological apparatus producing images that circulate in society and in which society recognizes its own stereotypes, it legends from the past and its imagined futures.”

Jacques Ranciere

Terry Ork

Gone Girl (2014). David Fincher, dr.

Over the last forty years the cultural landscape has changed dramatically. Media consolidation is one factor, and the continuing ascension of marketing and PR. The world that has been constructed by mass culture is far more intractable, it is more homogenized, more white, more pro military and more pro Imperialist as well. Take a show like The Blacklist. An amusing enough genre piece with a very effective James Spader in the lead. But the most recent episode, as an example, features a Mossad agent fighting a nefarious Iranian terrorist cell. These are the paradigms of mass culture. And it would be easy to almost randomly select other network shows and find the same manufactured political model. Less obvious are the deeper implications of film as an art form. For in this approach are to be found deeper political meanings. Ranciere quotes Michael Mourlet: “Cinema substitutes for our gaze a world in accordance with our desires.”This is true, up to a point, but the more significant question is what shapes our desires. Fincher’s film is an expression of a shallowness of desire, and to compare it to Hitchcock is to feel, on a primal emotional level, a lost world of other desires.

The Bad and The Beautiful (1953). Vincent Minnelli, dr.

The sense of film as mechanized Utopia has fallen away, and the bombardment of image, the circulating of image and mini-narratives, ad copy really, has now so saturated daily life that our perceptual processes are unavoidably linked to this machine, but it is an oppressive and intellectually debilitating machine now. Watching Minnelli’s The Bad and The Beautiful (1953) is to access another time. It is also a very early *meta* film. A film about the business of making films.

David Hall and Roger T. Ames have written several excellent books on Taoist thought and on Confucius. “It is the word picture as experienced by the celebrant of the poem and not (necessarily) the private experience of the poet, that constitutes the image. In fact, the most productive manner of discussing images is in terms of their communally experienceable character. Only such images are directly efficacious.” Thus, for example, the I Ching (Book of Changes) contains particularistic images, that are activated by a social memory based on traditions, rituals, practices and literature. As Hall and Ames put it, these images are ‘ritually protected’. In the West, at least since the Enlightenment anyway (but almost certainly in a different way, before) language has privileged the literal, the instrumental, the denotive. Metaphor is secondary, or parasitical (Ames and Hall), and this is worth noting here because of the extraordinary influence of screen image and more particularly of film and TV.

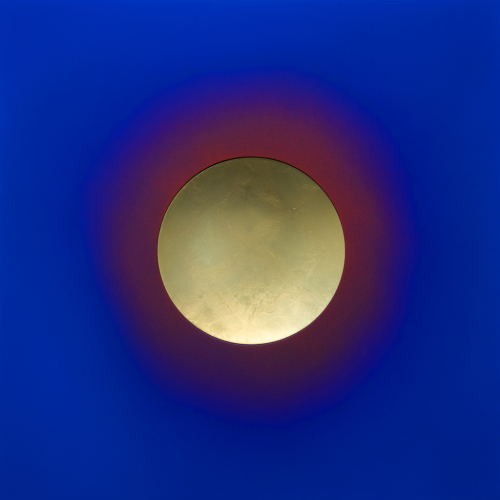

Lita Albuquerque

In the Minnelli, the quality of adulthood is a sort of background. The idea that making movies is for the immature. And yet the fictional producer Jonathan Shields seems to the world of 2014 remarkably adult. There is no snark. No sarcasm in the entire film. There is forgiveness, but not amnesia, at the end. And Minnelli was, of course, among the more elegant movers of the camera. It helps to have Kirk Douglas, when Fincher had Ben Affleck. The coiled sexual energy in Douglas is palpable, and like James Stewart, Douglas was able to get angry and take it to the extreme very quickly. That was the energy below the surface of Douglas. And it was in his body, and it spoke to something that relates to class. John Garfield had a walk that was not dissimilar. James Cagney, too, in a more exaggerated fashion. If sharks could walk, that is how they would walk. But there was never anything sadistic in Douglas’ eyes. He could portray a villain (Out of the Past for example) but there was never wanton cruelty in his eyes.

Now, there is another aspect to technique in film. Fincher is always cited as a technically masterful director. From one perspective he is, but from another, he is not. The quote from Lao Tzu at the top is a relatively obscure passage. But the short version is that *de* is short hand for authenticity. The man or woman in possession of *de*, the zhenren, is the one who is capable of having gone past mastery. He or she is master of the mastery. Hence, not in need of mastery. This idea runs very deep in Confucius and in Taoist thought. The zhenren, the authentic person, is transformative by virtue of having deferred to nature, and then incorporated nature. That deference is hard to translate, but it’s relational, and it negates by erasing the oppositional, through allowing it. It is actually very close to Adorno.

Ad Dekkers

“A work of art that fails to become its own most enemy remains the imitation of the muteness of history.”

Robert Hullot-Kentor.

Kentor quotes Wallace Stevens: “Art must be a violence against the violence; but if this violence is to be more than violence, what history presents art with must be returned to it pacified in form as memory.” I believe that is a paraphrase, and partly Hullot-Kentor’s commentary, but the point is that negative dialectics demands that art be impossible, and that it destroy itself in a sense. That sense in which it destroys itself is in mimesis. This is that sense in the viewer or audience or reader of the artwork that feels a helplessness. For memory is humbling. The cheap techno violence of most modern cinema is not just de-sensitizing, for it is that also, but it is there to create a sense of class hierarchy, and the illusion of power. For this pop-violence is not violent, it is fun, it is stimulating, and it is therefore allowed to be ideological. Maya Lin’s Viet Nam Memorial is the distillation of all wars, of mass industrial scale murder. The passage downward, to the underworld reminds us we are journeying across a dead zone, a killing floor of the soul. This is the Tao of violence in a sense. One of the most exquisite moments in The Bad and The Beautiful is when Jonathan Shields plays the recording of the actress’ father reading a monologue from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. There is nothing in the least portentous in that scene. The father is dead, there is only his voice. Reading a scene about death and fleeting existence. In the violence of today’s Zombie films or war movies, there is only camouflaged plunder, there is an unmistakable echo of the domination of the surplus population today. For all of it, from The Walking Dead to Homeland, there is the camouflaged pillage of Globalization. The latent meaning lays there disguised as aliens or viruses or Muslim terrorists, or vampires or zombies, all of them operating in their own slightly different register, but all of them reproducing the essential violent dynamic of this society. A violence directed from the privileged few against the disempowered many.

Homeland, 2012 (Showtime).

The fundamental unreality of this pop-violence allows a distance from any particular violence, and in that unrealness lies the smug condescension of the ruling class, of white supremacist Imperialist thinking. The increasing casualness with which this violence is depicted also reflects the indifference of those in power to those without power. Shooting hoodie wearing black drug dealers is simply and actually quite obviously the drama of colonial murder. The mistakenly released super weaponized bio-agent is the reproduction of smallpox blankets handed to Native Americans. And so forth. The unrelenting lack of compassion or, especially, forgiveness in characters in mainstream TV and film is the posture of the overlord dealing with a runaway slave. The unreal level of revenge in husband and wife stories is, again, simply reproducing the guard on horseback watching over the chain gang. Take your pick.

“The gesture draws on a vernacular nominalism that amounts to a procedural dismissal of whatever aspect of an object might lay claim to the universal as the objects own autonomy; this is rejected as fraudulent and an injustice for presuming to acknowledge anything that could come between the object and those uses that might be made of it.”

Robert Hullot-Kentor

On Adorno’s aesthetics

So, the technical facility of a Fincher is one that only tells the same story, yet again. It is almost intentional (if unconscious) in its superficiality. When Rosamund Pike murders her billionaire boyfriend in Gone Girl, there is only set design, and choreography, but no real violence. Nobody is upset by that scene. Nobody. The facade violence then serves as the plaster for the shape of movement which is reproducing this familiar sub textual story of class placement and social hierarchies. It is plastering over a skeletal frame that leaves only the contours of domination. Without that sexualized titillating violence the architecture of oppression lears back at the viewer undisguised, a grimacing death’s head.

Donald Judd (1968).

Of course there is also an ideological layer, the obvious one in which all Arabs are bad. So the Arab shooting the U.S. Marine is also, though, the plaster that allows a pattern recognition in which certain kinds of people are sacrificed to maintain order (power, property etc). The plantation owner becomes then, inversely, the Arab terrorist, and then they can easily reverse these roles in the next scene. For that violence is not real, it is carried out in sequences highly familiar, scored in the most familiar ways, and acted as if in an advertisement, a commercial. But in the end the raised fist is always the slave owner’s fist. Again, let me quote Hullot-Kentor on Adorno’s aesthetics: “By structure of law, we do not permit equality to be pursued except as a fulcrum of inequality.” So, since liberal *equality* still allows extreme privilege, homelessness, starvation, denied medical care, it therefore becomes the club with which to beat those not living up to this *equality* ideal. The white liberal has never forgotten that tolerance and equality were ideological weapons to protect his class interests. The mass cultural narrative is always telling stories of domination, even and especially if presented as stories of liberation.

The culture industry today, mass culture, hides its authoritarianism under masks with labels such as “human rights”, “equality”, and “anti violence” (or the Hollarback video etc). This is true, too, for celebrity left journalists from Penny to Danny Gold to VICE. All claims of barbarism (again, via Hullot-Kentor) or of brutal regimes, or of repression of rights, are always just echos of Lord Kitchner, of Empire, of King Leopold and the Raj. This structure and this grammar migrate easily enough to stories about Vampires or Zombies or super viruses. The entire Ebola narrative is one cooked up in some Hollywood office forty or sixty years ago. It is torn from the pages of Hollywood script labs, not biological warfare labs.

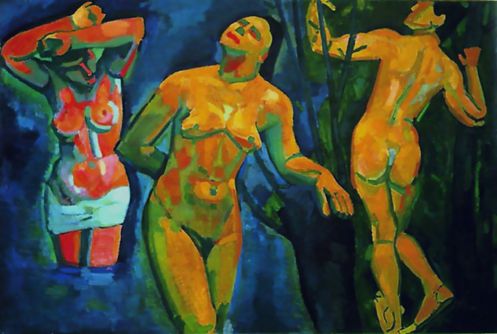

Andre Derain

The idea of equality also is a structure of grammar and linguistics. And of instrumental thought. Yet, there is still another aspect buried in this; the expectation of a climax, a denouement, and a resolution. The financialized invisible, the economic underpinnings that allow for an elite group the ability to grasp or to *see* equality etc etc etc, also exists only in exchange value, spread sheets and ledgers and accessed by those ‘free’ enough to devote time to ‘self improvement’, to ‘working on themselves’. The bourgeois balanced checkbook is the model of restrained critique, fairness, reasonableness.

Adorno of course was fascinated with the disenchantment of society. Today, the news, the left and right paid journalists, all decry the evil of ISIS, the barbarity of Russia, and the ruthless dictators of the South America. Molly Crabapple can write a sentence that includes “…the brutal Maduro regime”. The white mask of smug superiority — and this is the same mask worn in narratives like Homeland, but also is the same plastered wall crack that provides white men in costumes (ideologically and aesthetically speaking) acting out The Walking Dead‘s fight for survival. Reducing mankind to the level of primitive, as is the narrative of all zombie or post apocolypse films and TV, is really an understanding that we ARE primitive, and that maybe we desire it. The problem with all science fiction evolutionary tales of super minds or AI stuff is that we are actually heading in the opposite direction. Capitalism and corporate science is not reaching for the stars (except literally to strip mine them) but rather enslaving and holding society back, reducing it to a primitive state of dependence for shelter, food, and warmth. Education is destroyed, so that sci fi future of brainiacs is only a few white brainiacs on private jets served by indentured slaves. Evolution for the few.

The Man With the X-Ray Eyes (1963). Roger Corman, dr.

The West’s desire to conquer Nature is the antithetical stance of Taoism. The authentic person, the zhenren, dominates himself the better to defer to Nature, and merge with it in synthesis, and a mastery of mastery. The West’s idea of dominating nature starts with its acceptance of dominating man. In the false Missouri of Fincher’s Gone Girl, I was reminded of James Wright’s poem, Autumn Begins in Martin’s Ferry Ohio.

“In the Shreve High football stadium,

I think of Polacks nursing long beers in Tiltonsville,

And gray faces of Negroes in the blast furnace at Benwood,

And the ruptured night watchman of Wheeling Steel,

Dreaming of heroes.

All the proud fathers are ashamed to go home.

Their women cluck like starved pullets,

Dying for love.

Therefore,

Their sons grow suicidally beautiful

At the beginning of October,

And gallop terribly against each other’s bodies.”

It is one of the greatest of American poems. This is everything that Gone Girl was not. It was not Vertigo, it was not Minnelli or Ray or Mizoguchi, or Bresson or Godard. It was another Puritan cleansing of meaning and depth, of deep emotions. Adorno saw the truth of artworks in their form, and saw in their form the transcription of the history of human suffering. Instead, today, in mass culture the form transcribes only the history of domination, from the pov of the dominator. This was the message of Pasolini’s Salo. Today form is, in mass culture, the stern schoolteacher, ruler in hand, and in this interrupted gesture (per Adorno and Benjamin both) lies the latent sadism of all its meanings. It is not the violence of exploding zombie heads that should trouble us, but the violence of colonial plunder and conquest expressed over and over and over as the screeching tires of a cop car chasing a “bad guy”, or the nicely turned out woman lawyer working as DA, or the avuncular Uncle who makes funny comments in the latest sit com: for the really emancipatory in art is found in that which formally removes these meanings, and strips away the plastered holes. Art must negate that which is the whole, for, per Adorno, the whole is untrue.

One of the greatest of all science fiction films is The Man With the X-Ray Eyes, directed by Roger Corman. The dialectic of defeat has never been more clearly revealed. It is a modern Book of Job, and still, a sort of meta narrative recounting the history of micro budget B films.

James Wright

For Adorno, the negative dialectic meant turning violence against itself. The domination of nature, or conquest of nature, was the pre-history in ourselves, those archaic traces of the irrational. And only in negating it can come reconciliation. In The Man With the X Ray Eyes, the future of science is a nightmare of seeing that we cannot stop.

Titan missile silos, decommissioned. Location undisclosed. US midwest.

There is a whole discussion to be had around the dismissing of Freud by a society ever more dependent on, and linked to, an artifical landscape whose signposts were written in televisionese. The giant telecoms with advanced algorithmic analysis and data mining via the ever more invasive spy system of US/NSA/corporate controls has removed the personal choice in how to create ‘desires’ and ‘needs’. It is inching toward a total domination of data, applied in a weird logic of instrumental thinking to the individual shopper. Machines operate independent of human judgement. This marketing research, for that is in a sense what it all is, is now applied to most cultural product. Certainly to most TV and film. The fact that it is deeply flawed hardly matters because all outcomes are wins for the corporation. So, watching David Fincher’s latest film I couldnt help but realize that in a sense Fincher was accessing the reality as it is experienced by millionaire directors, who work for billion dollar studios, where marketing is based, largely, in the same machine logic as facebook or the NSA. The flatness, the loss of affect, that seems to peep back at the viewer from Gone Girl is the world as Fincher experiences it. Or rather, the world as Fincher ‘doesn’t’ experience it.

“Another way to describe the artwork’s masking of truth is to say that, instead of having or containing the truth, the artwork ‘reflects’ the truth, so long as reflection is here understood as a mode of mimesis.”

Tom Huhn

Introduction to Adorno

James Ensor

As a sort of thought experiment, it’s worth looking at talented director, a Cronenberg, and examine his early work in comparison with his later much higher budgeted work. Cronenberg felt creatively exhausted around the time of Spider. Now he makes bloated literary adaptations with high brow pretensions, and free of anything like his individual stamp — assuming one believes he had one. Videodrome certainly still feels like something special, and maybe Dead Ringers and Naked Lunch even. How does this relate to his ever increasing budget? Or fame? I don’t know. And its hardly a worthy experiment in the terms I’m making it. But my point is that Fincher is still making Nike commercials, essentially. We live in a society in which language has been altered into consumer-speak. Terms like ‘the private sector’, or ‘corporate family’, or any of the military jargon applied by the US press secretary, culminating in ‘disposition matrix’. These Orwellian terms are appropriated for entertainment purposes. Now, how does this link to film art? I think it’s partly linked by how difficult it is to make films such The Bad and the Beautiful today. There is nothing that is not connected electronically, and yet superficially. Text messages, twitter, social media, and just cell phones themselves have created a constant never stopping surge of information that people process quickly, in emotionally limited ways. Disposable information. Space is in flux, place is fluid, and I increasingly suspect that this quality of being ‘plugged in’ has very high psychic costs.

Thomas Eakins

It is worth remembering that Adorno’s criticism, in fact much of his writing, was not intended for the University. Benjamin as well, wrote for radio and newspapers. Peter Uwe Hohendahl points out that by 1959 Adorno was at a stage of acute disillusionment with the University, and the state of philosophy. He was aware of the shrinking sphere of public discourse of an intellectual or philosophical, or critical nature. The counter culture that appeared in the sixties was more complex than, I think, has been understood by many commentators. But in that interview with Penny Arcade, from which I pulled a quote at the top of this post, she reflects back on the Bohemia that existed in New York at that time. It existed in Los Angeles, too, and in San Francisco. It existed in London certainly, and in Paris. It does not exist in any of those cities now. There is no sense of an avant garde, and I find people in general to be very cynical about this topic, about the loss of an avant garde. The young tend to think nothing was really lost. And this is linked to the dissolving or end of modernism. The changing of New York, or at least Manhattan, from Bohemia to Mall took place over about twenty years. Certainly the New York of the 1970’s, when I lived in Chinatown and saw movies every day, is long gone. The post modern has come to feel increasingly like an advertisement for passivity. Mass culture feels increasingly like fascism. The forgetting of what radical aesthetic practice meant is costly, for in place of the avant garde one gets increasingly trivial comic books, or one gets David Fincher.

Artworks, and here we are talking more specifically about film, are not mimetically negating the world, or reality per se, but are negating the spell that is cast upon us. It is not reality but the spell — and this is crucial in understanding work that isn’t opposing this spell. This is a central tenant for Adorno, that the society of domination was in the process of destroying subjectivity. This is also where Adorno borrowed heavily from Freud; for he saw all artworks as illustrating the history of subjectivity. This is also why Ranciere saw the concept (if that’s what it is) of mise en scene as inevitably leading to a kind of wisdom. For the spell of reality, or the spell of an artwork, both exist only by the subject’s submission, or embrace, and this is the truth of mimesis. To express without reification, or in another sense, without objectification. But this expression is both fleeting, and historically mediated.

“The unity of the system derives from unreconcilable violence.”

Adorno

Zoe Leonard

Adorno believed that “legitimate works of art must without exception be socially undesired”. Now, the emigre psychoanalysts and artists who fled fascism, arrived on the cusp of McCarthyism, and their already well developed paranoia meant that they, at least superficially, tried to adjust and assimilate to life in the U.S. Psychoanalysis turned to adjustment, and artists looked to avoid overtly political statements. Even Minnelli, born in Michigan, was descended from Sicilian radicals and revolutionaries who were forced to flee Palermo after the uprising of 1848. The sense of exile ran deeply in all these emigre directors; Lang, Wilder, Siodmak, et al. The history of European culture and education was linked with oppression and flight. Tom Huhn makes a profoundly perceptive comment in his introductory essay on Adorno, when he makes mention of Freud’s aside that the history of civilization might be written using a chart that indicates the ever increasing use of soap. This also connects with Theweleit’s study of the German Freikorps; sexuality, fascism, moisture and dirt. Huhn adds that soap is the anti-mimetic, psychoanalytically speaking, and that Soap Operas were so called for a reason.

Syd Soloman

Soap then is a controlling mechanism for the psyche. And mimesis is stunted by the *too clean*. The point here is only that the work of these emigre directors, and their children (Minnelli) was mimetic in a sense that much later work was not. Mimesis is always in process, and must not stop for explanation, for that rigidity in form is, I think, akin to Reich’s ideas about repression and the rigidity of the body. The sensuality of Kirk Douglas vs the rigidity of Ben Affleck. The moist mise en scene of Minnelli and the dry and arid in Fincher. This is, no doubt, pushing this idea in a far too literal way, but it helps explain something of what has changed culturally over the last half century. The truth content of the artwork, to follow Adorno again, is reflected — and today, the unceasing production of kistch, and pop-violence, and reactionary work is reflecting back the already destroyed subjectivity of a culture of commodity fethishizing, conformity masked as individuality, and domination as freedom. The post modern expression, in mass culture, is repreating the same story, the same callus condescension and the same interrupted blow, the overlord poised to beat his servant while chatting to the cook.

I’ve noticed again and again when the vast majority of my community college students from other countries are shown Vertigo or The Bad and the Beautiful, Imitation of Life or The Searchers in my film classes, they react to scenes where emotion is expressed very differently than middle class white students from geographical areas that operate under under the thin veneer of supposed tolerance. These are the enclaves in the East Bay, places like Lafayette or Orinda or even Oakley. Any way, middle class students who grew up in such places almost always laugh, chuckle, or downright sneer at scenes where passionate emotion is expressed. Students newly arrived from Afghanistan, Central and South America, Russia, Turkey, etc or Muslims, Central American Catholics, however, rarely laugh and often show surprise at the students who do. Scenes of emotional violence are clearly painful for them to view. American middle class students for the most part can not process emotion in film, they need it to be snark or they convert it to snark or dismiss it as kitsch. Such students will tell me publicly they wish I would show current films, films more “with it”. But the rest of the students often in private conferences talk about seeing another world through the films and are perplexed why films they see in theatres today are so different from the films I show them. There is such a huge gap between the two groups that is superficially bridged only by discussions and further investigation by students into this question. I don’t tell them; they eventually, some of them any way, figure it out on their own when they begin to make their own connections to socio-political movements, such as labor, finance, the US military industrial complex etc. And then, of course, to capitalism, the destruction of their own countries by US imperialism, and advertising. I wish there were some framework for teaching such a vast amalgam of cultures in community colleges without trivializing either the content or the discussions.

@thanks joanna………..

very interesting observation. It really is. I think even very bright students, at university level, avoid an emotional framework that does not allow for a snarky escape. And i couldnt agree more about teaching. It really is time to stop such specialized instruction. Long overdue.

re SOap http://qlipoth.blogspot.com/2005/10/god-on-surface-of-skin.html…good stuff by the way on this in Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather

We watched Fincher’s Girl with the Dragon Tattoo recently. Such a strange sense of toying with a mimentic+symbolic chunk of stuff — sexual torture. The director gives us several scenes of torture presented unabashedly as entertainment, two surrounded by perfunctory disapproval that’s not suipposed to interfere with your pleasure (when the heroine being shackled and raped there is no suspense even laid in with the hope of her rescue, as their is with the hero;s torture) and one which revels openly in its pleasure-giving spectacle in which the deck is stacked so the audience is licensed to openly enjoy it (the torture by the heroine of her rapist social worker). Only the crude apparatus of narrative justifications distinguishes the presentations of torture…the style is the same, the appeal to sadism in the audience obviously the same. The director is definitely an adept — the film is expert technically, no longeurs, handles exposition easily, condensed storytelling — and that skill consists precisely of ways to feel audiences spectacles of torture for their enjoyment while managing their ambivalence about this pleasureable, and for many addictive, consumption.

ways to feed audiences these spectacles of sexual/eroticized torture that should say

i know the novelist was a real red and had a political motive here (to respond to the racist discourse in sweden associating violent misogyny with immigrants b y showing the violen t misogyny is linked with hatred of immigrants, that violent misogyny is homegrown and Nazi) and in the novel I expect these tortyres are not presented as candy for the beach readers infantile senses, but the FIncher film is nothing buit banquet of obvious emotional stimuli the piece de resistance of which is eroticized torture served in three courses with stuff between to enhance the delectation

@molly:

yes, the author was famously a Red. Also the swedish film is quite different in tone and intention. The girl is a far different creation, and her alienation is seen in a social context, rather than as just an eccentric *genius*. Her inner torment is central element in the narrative. The book even more so. FIncher turned it into a strange sort of cliche romance almost. But Im really struck of late with how homogenized are the values of US TV and film. The compulsive repetition of certain themes, certain political assumptions. And i think the white centered pov is becoming more pronounced. Since the films are so often about other films, the white center, the Imperialist center, seems a given, and its treated with more worship almost. It all feels, in tone, oddly Reagan era.

It’s a form of Mannerism, really — an ever increasing range of localised effects being used for an ever narrowing set of prescribed themes and ideas.

Thank you for the recommendation on David Hall and Roger T. Ames. I’ve just ordered their philosophical translation of the Dao de Jing.

Just to add a bit to Joanna’s experience, I used to go to a Buddhist temple that have their home base in Japan. I went to Japan several times and was also close to several Japanese people at home as well. When I would watch Japanese TV (and I don’t understand a lot of Japanese), I was struck by how emotional it was. Proper melodrama in a sense. Nothing ironic about it. In particular, men cry, especially older men. It isn’t a shameful crying. It is a sorrow from the depth of the soul – a real sense of humility and love. The women cry along with them out of sympathy and compassion. I also saw this regularly at the temple – I had never felt such real emotion in the US. It was in Japan that I learned to feel.

The older I get the greater difficulty I have in watching news programs, “comedy” programs, and any of the various brainless dramas. There’s no emotional content only empty forms; no contextual understanding, only “clean” (and therefore boring, trite) images. No questioning, only conformity.

@ m and Exir both.

great definition exir. You oxford guys. 🙂 And M, this is an interesting topic. I cant watch comedies. I cant do it. Comedies made say in the last thirty years. At least twenty years anyway. I cant do it. I get anxious. It makes me deeply uncomfortable. This sound of nervous laughter, and the sort of high pitched hysteria that is embedded in it, and if you see it in a theatre, that surrounds you in the form of audience hysteria. Its this barely suppressed hysteria. I think there is something very revealing in contemporary comedy. And Ive not quite figured out what it is. But i can feel it almost.

But there is, you’re right, a connection to feeling, to expression of feeling. Reich was right mostly. I have written of the gestural at times, the tense stiff bodies that seem to be the ideal now. For both genders. There is nothing of submission ….everything is aggressive and dominating. Body armoring. And the mannerist definition is correct….it is cinematic mannerism. And perhaps not even that. There were painters considered mannerist who i love….Joachim Wtewael for one…..but it is a kind of ossifying of relations in the image, or narrative. There forms sort of signifiers, placeholders, for where once there was a clarity in the relationship of the parts. It is replaced with effects, that indicate where a relationship is meant to be. They become sort of blueprints or prospectus for making art. Painting or film, anything. The localized effect is also a code. So a Fincher is operating this code, with great skill…..he is the Pontormo of mannerist filmmaking (this could get fun actually)…….but that trends toward emptying of deeper meaning, and of mimetic reading.

interesting related piece by brad evans. http://www.blackagendareport.com/content/why-barack-obama-more-effective-evil

Interesting essay and commentary. Not a style of discussion that particularly appeals to me but I do share the view that we need a good social critique of subliminal messaging in the media. I look forward to other such postings.

thanks peter.

I do have to say that there are problematic aspects to that Evans piece. Brad’s analysis is sharp, but the Rwanda material is horrifyingly wrong, and amounts to propaganda. And Jaar’s work is quite white paternalism. But thats for the next posting. The talking points are very relevant however.