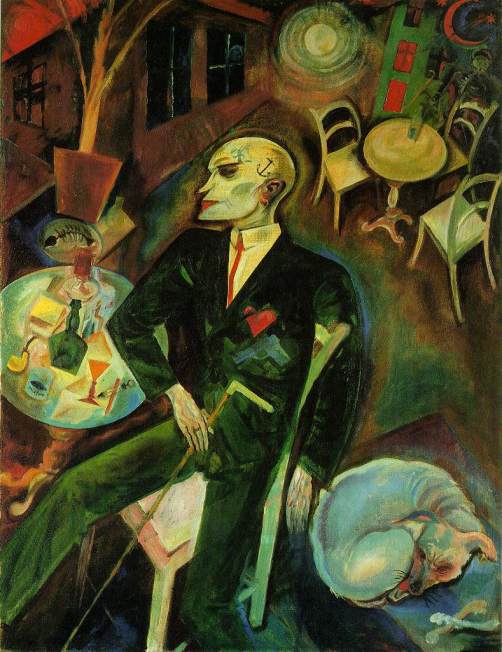

George Grosz

“Challenged, the coherence of myth became the myth of coherence. Magnified by history, the incoherence of the spectacle turns into the spectacle of incoherence (eg, pop art, a contemporary form of consumable putrefaction, is also an expression of the contemporary putrefaction of consumption). The poverty of ‘the drama’ as a literary genre goes hand in hand with the colonization of social space by theatrical attitudes. Enfeebled on the stage, theatre battens on to everyday life and attempts to dramatize everyday behaviour. Lived experience is poured into the moulds of roles. The job of perfecting roles has been turned over to experts.”

Raoul Vaneigem

“…let’s assume that there is a cinematographic modernity and that it confronted the classical cinema of the link between images for the purposes of narrative continuity and meaning with an autonomous temporality and the void that separates it from other images.”

Jacques Ranciere

Film is no more of a dream than theatre, it is only another kind of dream. It is the vast influence of film and TV today that has caused endless writing on the subject. I have said before that all discourse, or almost all, is now enclosed within the metaphors of film. More, people’s ideas today are shaped from within a cinematic framework, employing the narratives of film and TV. There is also something about the flickering lights on a large screen in a dark room, although they flicker less now due to digital technology, and I suspect there is a real oneiric loss in that.

Mario Schifano

Actors are doing something very different in film and TV than they do on stage. The reality of film’s effect has no doubt altered the dreams of people. The film actor is not even an actor, quite, if compared with the actor on stage. Certainly different directors have made quite different use of actors. Ozu rehearsed until there was nothing left of performance, and Bresson hired non actors, untrained at all, and moved them like puppets. Godard managed several things at once, often in the same film, and Melville had a knack for creating a distance between an actor’s persona and his performance. Elia Kazan treated acting much as one would in a certain kind of Stanislavksi based (by way of Stella Adler, Lee Strasberg, and perhaps Harold Clurman) theatre frame. Sidney Lumet was working out of that same method acting model, but working it out differently in terms of cinema. Pasolini worked in ways not unlike Bresson, and probably Antonioni was pretty close to Pasolini, and Fassbinder was working out of a model linked to Antonioni and Pasolini, but by way of Sirk. And that is a fascinating linkage here. Douglas Sirk, the most enigmatic and difficult of major film directors to talk about. One famous essay was titled “The Impossible Cinema of Douglas Sirk”. And it’s true. Sirk actually used the most dreadful of Hollywood stars and starlets (by necessity) and transformed their wooden emotionless beauty into the appearance of grace. I always think of Von Kleist on marionettes when I see Sirk. But Sirk was not unlike Hitchcock in that sense. There is a subtle form of irony nipping the edges of each frame.

The idea of the performance on stage is implicit with a direct relationship to the audience. Everyone is in the same room. There is ritual space created, an unconscious looms off stage, and however that ritual is played out (and I’ve written of this before) whether in Noh, or south Indian dance, or in Pinter and Beckett, the actor is both spiritually naked (as Artaud desired) and reciting a memorized text aloud. He or she is performing a text, from memory, in some sort of *performance*, some deep relationship with story as allegory. In film, the actor is not present. He or she is rarely really reciting any complex narrative. The ritual does reside within a special space. Film is image, it is the ritual of the camera. The camera documents something.

“This space and time peculiar to the image is none other than the world of magic, a world in which everything is repeated and in which everything participates in a significant context.”

Vilem Flusser

Harold Hausewald, photography.

The audience for film (and photography in another way) creates temporal relationships. The memory of rehearsal in theatre, of memorization, becomes a recurring process of mimetic re-narration in film, the actor’s job has migrated to the viewer. Flusser points out that in photography, which is meant to be a map (partly anyway) the actual role has become a screen. This is even truer, I think, in film. People project movie screen images outward, and life becomes a movie. Flusser suggests amnesia is linked to people forgetting they created these images, and they created the technology that creates images. The result of projecting a screen world outward is that imagination dries up. Flusser says imagination has become hallucination. Now one of Flusser’s ideas is that the invention of linear writing was born of the need to create comprehension of the sensory world. The circular world of pre-history became the linear world of modern history.

There is a complex set of relationships still being worked out between language, technical image, and traditional image (say painting). If one believes Flusser the invention of technical image signaled the start of post linear history. I’m not sure that’s quite right, but it has certainly mediated conventional processing of memory and what is thought of as history. And the hegemony of film and TV narratives have replaced the de-coding of everyday images with the de-coding of technically produced images. A new magic that valorizes the technical which created the process. The constant flow of images is so great that that, per Flusser, the dam (his metaphor) starts to overflow. This is also related, I think, to Beller’s idea of a surplus unconscious. Humans can longer process images fast enough. Now in movies, the narratives are imbued with this new sense of magic. I think that the resistance felt to ideological readings of films and TV has to do with the sense that the technical image is self justifying. It is accurate. This reproduced *reality* is more real, more historical, more truthful that linear language based reality. Except of course it’s not. Mass culture is digitalized memory mush.

Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980). Rainer Werner Fassbinder, dr.

What interests me here is less the philosophical implications of technology, but how films have served to manufacture consensus about certain things. Or maybe, more accurately the ways that film has shaped discourse and consciousness, and the role of art in destabilizing this.

Brad Evans recently posted in social media this quote of Ranciere, and I think it speaks to this:

“We have to revise Adorno’s famous phrase, according to which art is impossible after Auschwitz. The reverse is true: after Auschwitz, to show Auschwitz, art is the only thing possible, because art always entails the presence of an absence; because it is the very job of art to reveal something that is invisible, through the controlled power of words and images, connected or unconnected; because art alone thereby makes the inhuman perceptible, felt.”

The democratization of creating technical images has also trivialized the role of narrative, of de-coding the world. The casual indifferent photographer sees no responsibility in creating images. But movies are created in a way that mirrors theatre in a sense, or the creating of any art. They negate the everyday indifference, in theory, and present special moving images meant to be received as narrative. Now the amazing volume of film and TV narrative however has come to be almost as incomprehensible as the numbers of cell phone photos. The ritual has been worn down. And more significantly the vast majority of film and TV is manufactured by corporate entities, by the ruling establishment and it’s lackeys. It is recreating over and over again a picture of a false reality. It is ratifying and validating a very specific set of illusions. But it also in the truest sense fetishizes images. Images are narrated. They are given codes. The current NED sponsored demonstrations in Hong Kong are sold to the U.S. public who has learned the narrative for ‘crowds in the street’. If there are crowds, it must be an organic protest to fight injustice. Same as Venezuela when right wing students, a minority, agitated and made sure to photograph it. Same in Georgia, and Ukraine. The narratives are the narratives of coded imagery.

The Film Sufi blog wrote this about Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac:

“Similarly Bresson tends to avoid establishing shots from an “objective” perspective and instead presents fragmentary, impressionistic static shots of body parts or other objects that reflect mechanical operations. They are the kinds of odd images that might be stored in one’s memory, like mental snapshots associated with a remembered scene.”

This is a very astute observation for that is exactly the experience for the viewer of Bresson’s work. One remembers. But what does one remember? That is the enigma.

L’Argent (1983). Robert Bresson, dr.

Bresson was one of the three directors Paul Schrader singled out in his now quite well known book “Transcendental Cinema”, along with Ozu and Dreyer. It is possible that Bresson remains the most complex of these three. Dreyer is probably the most austere, and Ozu the most reconciled to the tragic in life. Its also possible none of that is true because in each of these directors there is an infinite amount to experience and re-experience. A student asked me once for my favorite Bresson film. I wanted to say Pickpocket, and many people would, or A Man Escapes, or Au Hazard Balthazar. Few would pick any of this late color films. However, as time has passed it is quite possible that in differing ways both L’Argent and Lancelot du Lac have emerged as just staggering masterpieces, but ones that it takes years (decades?) to find affinity with and fully appreciate.

Incineration plant. Roskilde, Denmark. Erick van Egeraat architect.

Now this incineration plant is of an architectural design shaped by film. This is movie set built to mask the actual plant. Its decorative, though rather appealing, but the message is filmic. Its kitsch architecture. Hardly the worst by any means, but the vision for this incineration facility was one born of Hollywood’s apocalypse themed movies.

Magnificent Obsession (1954), Douglas Sirk, dr.

One of the realities of the new magical post linear narrative is that it justifies white supremacism and erases class.

“This produces racism. Racism isn’t just a bad feeling in your heart, as a liberal believes when she insists that she isn’t at all racist. It’s a force that emerges from the pressures of maintaining one’s own position, and the resentments that spring forth from this process. It produces fear and hatred of the poor for being poor, for having any pretense of being on equal footing with the propertied. It is a hatred for the potential threat to the property values which underpin a tenuous future among the professional middle class: blackness.”

Gavin Muller

In mass cultural product, and I’m thinking here of corporate news, Hollywood film, and TV, those manufacturers of technical image, the narratives have coalesced around the selling of fear. This is logical since the people who own the means to make and more importantly to distribute technical image are very wealthy and almost always white. They create a magical story that connects fear with the poor. And especially with poor black men. They spread it around though, for barrio neighborhoods are increasingly used for variation, but function much the same as black ghettos have for thirty five years. It’s not hard to de-code network cop shows for example. Now increasingly there is the creation of imaginary landscapes of white stability. It is interesting and instructive to watch the UK mini series of a year ago, Broadchurch, and compare it with the U.S. remake this year titled Gracepoint (starring the same actor, Scotsman David Tennant). The UK series was really about the malaise of a dying seaside town. The frustrations and pathologies of those deprived of hope. The mystery was far less important than the personal struggles of the populace to keep their sanity. It wasn’t brilliant but it was intelligent genre television. The U.S. version — of which it has to be said only the first episode has aired — is set in a fantasy small town the likes of which exist nowhere in the United States. The rhythm of the editing, the camera’s creating of artificial tensions, and the sense of mechanical rote storytelling all serve to register this small town as ordinary. The culture industry loves this faux ordinary. It’s not ordinary. Its dishonest and a fantasy. The characters are dishonest and unreal. There is no such town or any town that resembles it. It is supposed to be set halfway between San Francisco and the Oregon border. You know what towns are like up in Humboldt County? In Mendocino county? Where the ONLY prospering industry is illegal marijuana growing, now encroached upon by cartels and policed by private security firms (i.e. mercenaries).

Abandoned NWP train yards, Eureka Ca. 2002 (photo courtesy of History of Fortuna.)

The towns up there are paranoid and economically marginalized, they are culturally narrow and intolerant of outsiders. Is Gracepoint a version of Fort Bragg? Where one could visit ‘glass beach’ the site of decades of dumping by residents and small business, on land owned by the Union Lumber Co. Where garbage is so high its often burnt off. Georgia Pacific shut down their mill, terming it a ‘non performing asset’. Median family income in Mendacino is around 37,000 dollars a year. In Humboldt over a third of the economy is pegged to marijuana, so statistics are unreliable. Maybe Gracepoint is supposed to be a version of Eureka? The mean family income is 27 thousand a year, and the racial make up is 80% white. The lumber and fishing industries are dead. That leaves….mostly marijuana again. Roughly a quarter of the population of twenty five thousand live under the poverty line. Maybe its meant to be Del Norte county, one of the smallest and poorest in California. Mean income 28 grand a year. Notable for *Bigfoot* sightings and home to Crescent City, a town routinely devastated by tsunamis due to the peculiarities of the its coastal geography. Speaking personally, Crescent City remains among the most depressing places I’ve ever passed through. But Hollywood doesn’t investigate reality, not personal, not social, not political, not anything. This is a world based on other movies which were based on yet other movies. Every show reflects the schools, dinner parties, clubs, and streets of the creators of these shows. Ergo the streets of affluent white people. Women who have a fair amount of plastic surgery and time for a personal trainer. Men who have a fair amount of plastic surgery and time for a personal trainer. Both can afford shrinks. Most make use of them. Anytown Kansas looks now like Brentwood or Pacific Palisades or Santa Monica. The entire story of Gracepoint is washed away because it takes place at Disneyland USA.

Broadchurch, created and directed by Chris Chibnall, ITV, UK, 2013

Now it is worth pondering why, say, a Sirk, a director who transformed trite melodramas into something surreal and unsettling feels so different than shows like Gracepoint. Imagine Sirk shooting the opening episode of Gracepoint. Even in the hands of Todd Haynes the difference would be substantial. But Hollywood works off copies of copies of copies.

This takes us back to Bresson and the enigmatic. For there is something very different in the eternal recurrence of myth and allegory, which is housed in deep memory, and that endless loop of mass mush that is the product of corporate owned film and TV. Those narratives that repeat, compulsively, the same unreality are there to destroy imagination, and to make the viewer forget. Image is now circulated as a marketing tool.

Fra Angelico (detail).

Thinking however, of great film acting, means looking at Brando in The Fugitive Kind, at George C. Scott in The Hustler, or Peter O’Toole in Lawrence of Arabia. These were performances that defied the camera. But in both Scott and Brando there was always the sense they were acting in a different movie from everyone else. They did something that posed a negation of the camera’s tacit role in memory. Today I think, if asked, the two greatest living actors are Rory Kinnear and Jeffrey Wright. Both have certainly done a good deal of crap film and TV. But both have, at times, in places, captured that fleeting magical sense of deep memory. But both are technically brilliant actors. I am not sure that this, in the end, means very much. At some point, at least in film (Kinnear did a now nearly legendary Iago a couple years back at the National Theatre, in London) they must reach past whatever it is HBO or Showtime is offering. But these are the contradictions of film, and they can be traced back through the economic aspects of film, and the very origin of it. Photography is different. And perhaps worthy of an entirely separate discussion.

George Shaw

“Cinema revokes the old mimetic order because it resolves the question of mimesis at its root.”

Jacques Raciere

Ranciere quotes Jean Epstein from a 1921 essay, saying that in effect film is a form of mind. I think this isn’t quite right. I think theatre is a form of mind, a form of thought perhaps. Film is a form of memory. And this Ranciere would probably agree with. For film is also inherently about nostalgia. It is, in its technology, part of a civilizational moment of promise, the instrumental dystopia of progress and with that, of conquest. Film was bound to quickly turn to stories about film. But film is, like theatre, connected to dreams. The audience does not dream film, film dreams the audience. The audience is snared, in a sense, caught in the spell of the apparatus and its documenting, for the film camera is a machine to which actors sacrifice themselves. They do it both in career, but more interestingly they do it before the illusory alter of the apparatus. The screen *performance* is one of abjection and supplication. I suspect Brando knew this better than most. Nobody was beaten up more convincingly than Brando. Nobody sensed the ways to counter the documentary machine quality of the camera, and appear to it as a surprise.

A Man Escapes (1956), Robert Bresson, dr.

There are directors today, Bruno Dumont, Amat Escalante perhaps, Guiraudie, maybe Michael Haneke, that I think are aware of and trying to work through the possible disruptive techniques of the camera. Dumont is an obvious legatee of Bresson. Jacques Audiard, and maybe Lawlor and Malloy, and a few others, are working through the sense of text more. Of mainstream directors its possible David Fincher deserves some credit for at least a semi formalist approach to making junk. Paul Thomas Anderson is another conflicted case. The Master was elegant, both cinematically and textually, even if the whole was less than the sum of the parts. He has made dreadful stuff like Magnolia, and then made an operatic somewhat de-politicized adaptation of Frank Norris’ novel Oil (There Will Be Blood). But even here the film is working off the *star* doing some version of a *star* performance. Its effective. But it diminshes what might have been something more. Fincher and Anderson are astride the commerical world of technical dreams and the world of deep memory and allegory.

But, if one sits back and watches Fincher’s films again, something unpleasant takes place. For these are the films of a man who graduated from advertising, and directing commercials (Pepsi, Sony, Nike, etc) and music videos. He is the very talented child of regressive consumerism. Fincher will always be a bourgeois filmmaker making bourgeois films. Anderson seems far more intriguing, and in fact, with The Master has made a pretty memorable film that is working off the ideas of subverting the false present. The Master is about memory. It is a movie about failed memory.

Party Girl (1958). Nick Ray, dr.

Still, compare to Bresson. Ranciere wrote that in what defines Bresson’s cinematographic art is that which is found in theatre in the *third character*, or unknown, or inhuman. I wrote recently about the idea of what defined theatre, and why one-character plays were missing something crucial. This is a closely related topic. For Ranciere has touched on a profoundly important aspect of creating film (or theatre). That is the unknown voice, or the off-stage, or in film, more specifically, a reconciliation with the camera. The camera is the voice that doesn’t speak. If you do not understand that, you can only make elegant commercials like Fincher, or inelegant commercials like Tarantino. The voice that is mute, or refuses to speak, is that same force of memory and the uncanny that one experiences from the off-stage.

Sam. P.K. Collins, writing in Think Progress:

“Americans are more depressed now than they have been in decades, a recent study has found. San Diego State University (SDSU) psychology professor Jean M. Twenge analyzed data from nearly 7 million adolescents and adults from across the country and found that more people reported symptoms of depression — including sleeplessness and trouble concentrating — compared to the 1980s.

Twenge’s findings show that teenagers in the 2010s experience memory trouble 38 percent more often than their 1980s counterparts. Teens are also 74 percent more likely to have trouble sleeping and twice as likely to see a professional for mental health issues. College students in the study reported feeling overwhelmed by academic and personal demands 50 percent more often than their 1980s counterparts.”

Now this is admittedly not exactly the most scholarly of journals, but one thing is interesting. Teenagers with memory problems.

This is the generation of the screen. The generation born of a generation that was half screen. Of course they suffer from dysfunctional memory, mass culture has seen to that.

Now, one other aspect of kitsch film today, at least of Hollywood film and TV, is the glaring narcissism of the white world. I cannot remember a show where someone did not have hurt feelings. Deeply hurt feelings. I cant believe there has ever been another culture in the history of the world in which any peoples have so enjoyed and desired and luxuriated in feeling affronted, or insulted, or shown insufficient respect. Hurt feelings are ready to pounce at every turn, same as those serial killers/rapists/child molesters/aliens/zombies that are around or behind every pillar or car, or in every shadow of the parking garage or stair well. Any part of the urban landscape in which the poor might have access is treated as hostile.

Max Klinger

The white liberal class today deems the world inadequate to it. And this finds expression in the racism that haunts daily life as well as cultural production. Narratives reflect this larger feeling of the world’s deficiencies by making it personal. Stories are about others letting you down. Father, mother, brother, sister, husband, wife, friends; they come to stand in for the sense of dissapointment the narcissistic white West feels today. The poor are disruptive wherever they appear in this world. Class segregation is mandatory. The appearance of the poor, especially black poor, disrupts the sleepwalking daily life of the affluent class. Running alongside the sub-text of the inadequate world is one that seeks to create menace lurking in the marginalized masses. The disruptive effect that occurs when the poor become visible is narrated as a disruption having justification. The Ferguson Missouri resistance is narrated by suggesting “outside agitators”. The implication is both that the poor black community could not organize themselves, and that no doubt some form of dissident outsiders have infiltrated the protests. This is a narrative with a long history in the U.S. Either way, the fact that poor resist is an affront to white sensibilities. That alone is enough. (See the Manyfesto blog here: http://manyfesto.org/2014/09/05/red-baiting-as-the-cliff-approaches/) The emphasis in mainstream cultural product, in TV and Hollywood, is always on individual accomplishment, and it discourages any idea of community. I’ve also noticed that the most popular villain in mainstream material is one now labled as ‘eco-radical’. Environmental extremists. Its pure fantasy, but it creates yet another excuse of police power. Driving these fantasy story lines is the desire to believe, to keep in place, the constructed movie screen being projected on the world.

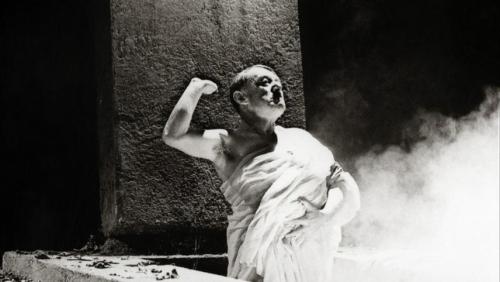

Our Hitler (1977), Hans Jurgen Syberberg, dr.

The role of aesthetic education is to start deconstructing these thematic issues, but also to question the form. The constant non-stop bombardment of amnesia producing kitsch. If the most critically acclaimed film of this past year is Boyhood, then it is clear that only the most glaringly superficial depictions of white virtue are going to be disseminated. The endless stream of hyper violent cop shows feel ever less meaningful in terms of conditioning. The educated class are being trained to evaluate art in terms dictated by the corporate ownership class. By business directed criteria. There is nothing in Boyhood that is not regressive. Performances take place in a fantasy landscape borrowed from earlier films, it is the SAME landscape as Gracepoint. This is a more insidious and pernicious film than even Zero Dark Thirty. It appeals to an educated audience, and it is validated and described in ways suggestive of serious art. This brings me back to the Ranciere quote. There is no depth to Boyhood. There is no memory, and yet it is a film *about* memory, and the 12 year shooting schedule ‘proves’ this. There was an understandable but small rejection of Zero Dark Thirty (or Lone Survivor et al) but it only has served to soften the response to stuff like Boyhood. At least its not violent. My argument would be that such craven sentimentalizing is every bit as violent; it is a violence that erases dreams, it extinguishes memory, and obstructs mimesis. People today do not want to be accused of ‘hating everything’. Of being ‘so negative’. There has never been a time in which to be more negative. There will be a predictable response to saying this, the inflated ‘reasonableness’ of the educated white liberal will denounce such talk as exaggerated, as sweeping generalizations. But this is exactly the sound of characters in corporate entertainment. They are speaking lines from their favorite TV show. Aaron Sorkin doesn’t write dialogue like people talk, people talk like Aaron Sorkin writes dialogue. They talk like Michelle and Robert King, like Joss Whedon, like Dick Wolf staff writers, like Bochco and Milch, like Howard Gordon.

Francesco Furini, 1640.

But there is plenty of stuff not to hate. Only it requires effort to find it. Mister John is not an easy film to see, as an example. Neither is Stranger at the Lake, not even Blue Caprice was widely seen.

When one looks at the films of directors like Nick Ray, as an example, it is easy to miss just how strange and disquieting his images actually are. Ray himself probably didn’t quite realize the extent of his cinematic gifts. To watch, anew, the strange poetics of Ray’s films is to suddenly see the potential of film art. I cannot even remember the plots of most of Ray’s films. I do remember my emotional state when viewing them, however. The west today is taught not to look. If I take a moment and sit and look at Francesco Furini’s paintings, as an example, I see what somehow feels as if it should be familiar, but it is not. The viewer is gazing from an indeterminate location, and the atmosphere feels exotic, though nothing specific suggests the reason. A student of Caravaggio, Furini is the toxic shadow to Caravaggio (if that were possible). His paintings suggest an erotic distress, if not morbidity. Something is not as it should be. Certainly his paintings do not suggest happiness or joy. I’m not suggesting Ray is the filmic Furini (though thats a sort of cool idea in a way) but just that in his films, things as not as they should be. This is a negation of the standing world, but it is not explicit. The banality of Linklater’s work is acute. It is mentally paralyzing. Hence, he will be critically rewarded. It is important to teach how to *see* Ray. And Straub & Huilett, and Bresson, and Godard, and Pasolini and Fassbinder, and Tarkovsky, and Antonioni, and Syberberg, and etc etc etc.

Art is not the only thing possible, but it is one of the only things. The atomizing, snitch centered, shame driven and punitive culture of white America is eating its own brains. It is a vampiric Ouroboros, a soul killing culture of blatant racism and fascist sympathies and it is in flight mode, like a mad King backed into a corner.

Thank you.

I recently watched Boyhood, and it was pretty abominable for sure. I was almost downright offended by it for more reasons than one. In film in general today I often sense a cinema of ‘non expression’ embodied in France by the dreaded triad of Assayas, Desplechin, and Ozon, with Kechiche an offender as well. Summer Hours is about as reactionary a film as I’ve seen in recent years.

@remy………..yeah, I *was* offended I think. Sometimes i sort of ‘get’ why certain bad films are popular. Its predictable, they cater to various notions of ‘seriousness’ etc. But Boyhood was such terrible filmmaking, firstly, and so mind numbingly regressive.

“The emphasis in mainstream cultural product, in TV and Hollywood, is always on individual accomplishment, and it discourages any idea of community.” As soon as I read this I immediately thought of/applied it to Alex Perry’s piece in Newsweek on George Clooney and South Sudan. I find it somewhat galling how much emphasis is put upon, and embraced by, an individual with regard to a country that has suffered so much from war and imperialism. The fact is that Clooney’s fame & fortune were generated via Hollywood (which serves empire and promotes a western lifestyle) and he now lives in a way that is supported by the same forces that are tearing countries apart. The “product” he sells (and Clooney is actually a sponsor of Nestle’s Nescafé) is itself destroying the world he wants to “save”. As always, the focus is on one person, the individual waging battle against…well…what? A system from which he has benefitted and is sustaining? This meme of an “individual savior” is one that has not only become worn thin, it detracts from the larger sense of community and what could be accomplished working in unison. We accept this cliche since it has been pummeled into our brains since we first sat in front of a TV. But it is not real even though it appears so. It is a fake script for us to emulate and the results are catastrophic.