R.H. Quaytman

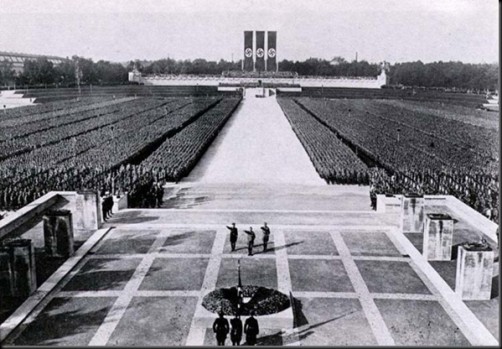

“In the 1970s, I met Leni Riefenstahl and asked her about her films that glorified the Nazis. Using revolutionary camera and lighting techniques, she produced a documentary form that mesmerised Germans; it was her Triumph of the Will that reputedly cast Hitler’s spell. I asked her about propaganda in societies that imagined themselves superior. She replied that the “messages” in her films were dependent not on “orders from above” but on a “submissive void” in the German population. “Did that include the liberal, educated bourgeoisie?” I asked. “Everyone,” she replied, “and of course the intelligentsia.”

John Pilger

“If place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which can not be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place.”

Marc Auge

During this week of Israeli ethnic cleansing, its good to be reminded that the those trying to resist occupation, or invasion; those fighting against colonialism and Global Capital are usually portrayed as villains, as malcontents, as terrorists. They are the trying to expel the West, after all.

In 1948 a letter was sent to the New York Times, signed by a number of Jewish intellectuals including Albert Einstein (who is seen as the main creator of the text) and Hannah Arendt.

It begins:

“Among the most disturbing political phenomena of our times is the emergence in the newly created state of Israel of the “Freedom Party” (Tnuat Haherut), a political party closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties. It was formed out of the membership and following of the former Irgun Zvai Leumi, a terrorist, right-wing, chauvinist organization in Palestine.

The current visit of Menachem Begin, leader of this party, to the United States is obviously calculated to give the impression of American support for his party in the coming Israeli elections, and to cement political ties with conservative Zionist elements in the United States. Several Americans of national repute have lent their names to welcome his visit. It is inconceivable that those who oppose fascism throughout the world, if correctly informed as to Mr. Begin’s political record and perspectives, could add their names and support to the movement he represents.”

Ordensburg Vogelsang. SS training center, built 1930’s.

La Vele di Scampia, Naples. Tobias Zielony, photography.

Tobias Zielony did a fascinating photographic essay of La Vele de Scampia, and I use two of his remarkable photos in this posting, but the accompanying text, by Shauna Thompson reveals the problematic interpretation of such failures.

“Zielony’s photographic series, Vele, alludes to the legacy of this place: the failure of a utopian architecture that has literally and figuratively crumbled into a dystopian reality that is at once both nightmarish and banal—the hubris of a government that would insist upon an architecture with social goals in a place where social problems were largely unaddressed. A nine-minute photo animation of a combined seven thousand single images offers a shifting, hallucinatory portrait of the place and some of its inhabitants, while a parallel series of photographs depict still moments of the same.”

The failure is not with Utopian architecture, or rather not per se. The failure is very precisely with government failure to address social problems. There is a subtle implication (and I’m being overly harsh with Ms Thompson) that a government with social goals is deluded. Most readers and viewers of this exhibit will come away thinking, oh, another naive Utopian dream doomed. And they will no doubt assume it is more proof that what is needed is a free market, where the poor can become rich and build their own ugly McMansions. Except that never happens. Today there is a tacit cognizance that society is indifferent to your wants. That society is cynical. But it is true that most Utopian model cities have come out of architects themselves not sensitive to historical formations of community.

That said, Zielony’s photographs are quite compelling and haunting.

‘Scampia’, Naples. Tobias Zielony, photography.

Here from the catalogue to Zielony’s show in Naples, at Galleria Lia Rumma Naples: “If you’ve seen the movie Gomorrah, you won’t have any difficulty recognizing the location of Tobias Zielony’s photos: Le Vele (The Sails) in Naples. Denatured by modifications to the original plans, obstructed by management failures, excessive housing density and insufficient services facilities, the monumental buildings are to be demolished. Three of them have already been razed to the ground. The remaining four “sails” are in an advanced state of degradation. Only about a hundred families still live in buildings which have now been reduced to ghostlike ruins”

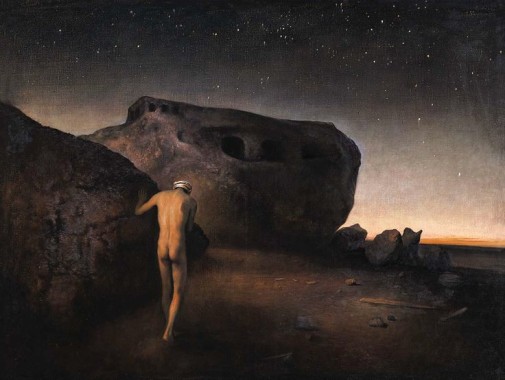

Fritz Stern (and Hobsbawm) saw the early 20th century as period where the past was being re-imagined, and viewed as (in Stern’s phrase) as a “springboard to the future”. History was being invented, posited, as an era bathed in amber light and with Volkish medieval style codes. The final expression of this was National Socialism.

Odd Nerdrum

“I begin here not with a French apartment tower but with the Bauhaus, the school that was founded in Weimar, Germany in 1919 by Walter Gropius. The Bauhaus can be looked upon as the fountainhead of the modern movement in Germany and in the Scandinavian countries. I show … the cover of the first Bauhaus Manifesto, from 1919. It is a cathedral. It is actually a Romanesque cathedral. The text that accompanies this image talks about a new architecture, which is going to create new ideas of community. In fact, the cathedral itself was described in Bauhaus publications as the “cathedral of socialism” or the “cathedral of the future” or the “cathedral of freedom.” Here and in other places at the same time Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus, summoned contemporary artists to join in the “cooperative work” of “kleinen fruchtbaren Gemeinschaften, Verschwšrungen, Bruderschaftern . . . . BauhŸtten wie im goldenen Zeitalter der Kathedralen!”, to join, that is to say, in small communities or brotherhoods such as those that built the medieval cathedrals. So the “cathedral of the future” in the Bauhaus Manifesto was a metaphor for a temple to secular regeneration after the war, for the creation of small new communities, led by artists, that would then be the basis for spiritual regeneration.”

Barbara Miller Lane

Now, as I’ve said before, I think LeCorbusier is often misread, or read reductively. Pre WW1 architecture in Germany, and really, in all the arts (though in different ways and to differing degrees) was linked to Protestant symbols borrowed from Medieval building and painting. In Scandinavia, there were various threads from Denmark, Norway, but perhaps most important were the Finnish art nouveau architects like Eliel Saarinen, and painters such as Akseli Gallen-Kallela. There’s was a northern mythology of primitivism and pagan kitsch and this was possibly as influential to German design as anything in German speaking countries at the time. All this is just to say, The Bauhaus and the Russian Constructivists (and the Russian Revolution) radically altered ideas of the relationship between communities and space. What they had rejected so concisely was almost as significant as what they created.

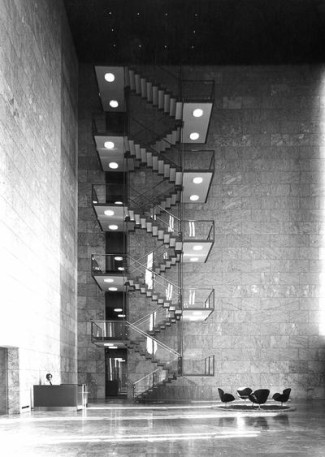

Danish National Bank, Arne Jacobsen architect, 1966

The erasing of Utopia is both cause and effect of the rising authoritarian values and an increasing acceptance of pure fascist politics in the advanced West today. When there is nothing in this imagined future but the false memory of cheap national chauvinist mythology, then the badly educated populations of the West are finding their only consolation to dreary emotionally nullifying wage slavery by dreaming in images of a false memory. The new Albert Speers are cybernetic, and the Spectacle is immaterial, and Hollywood continues to manufacture false memory. Perhaps it does that before all else.

Helsinki Central Railway Station. Eliel Saarinen architect. 1919.

The real problem with Utopian city planning is that it often, or perhaps usually, neglects the historical and the relations forged in daily life between the populace and things like buying food or clothing, access to health care, etc. The problem is often that Utopia is a-historical. But why is that? Partly, it is the Spectacle itself, the entire vocabulary for architects has been cleansed of alternative thinking. Past a certain point, history is torn down in the same way the slums are cleared away. For the shanty towns and favelas and ghettos of giant global cities are the repositories of history. History and memory live in these places.

Carel Willink

“If we try to apply these thoughts to the fields of architecture and urban planning, it seems that the speed and spontaneity of our changing societies makes a programmatic determination of spaces practically impossible. Thus we have to fundamentally question the idealised condition that architectural practice takes as its starting point; this neurotic tradition that has been passed on from generation to generation of architects. Instead of reproducing the institution’s spaces of control, we have to face the absence of expectation of programmatic control.

One example: we know already about the demographic transitions taking place in Latin America, where a very significant decline in the nuclear family is generating a need for a much broader diversity with respect to rooming schemes. But architecture just keeps on reproducing (on a large scale) homes and housing for traditional nuclear families. And at an urban level, public policies, governmental structures and developers are continuing to define our production of space.”

Michael Rojkind

In a sense, what Rojkind describes in architecture is true in narrative, in film, in all art. The reproduction of tropes of control, of spaces of control, and the imposing of norms for behavior, and setting of values. The narratives for Hollywood today are simplified to the level of Dick & Jane readers. And the kistch War Gods of Nazi mythology are completely at home in this programming of the people, and in the most basic vernacular. This is the Hollywood template, and the new worship of the military and police is always in service to these Gods. Now, what Marc Augre called “non spaces”, in his view of super modernity, is really most public space today, at least in the U.S. Airports, highways, malls, sports centers, even super markets. In each case, history is absent. The airport, or train station and bus depot are all expressing temporality. You cannot stay past your travel date. Your shelf life is short. Nobody waits at any travel hub for more than 24 hours. You are given a ticket number, a seat number, and a time. And you are watched. In the U.S. the effects of automobile orientation is profound. And the gas station is now an iconic and even romanticized symbol of an ersatz freedom of movement. And indeed, at ground level, the gas station possesses something far less controllable than airports or train stations. I suspect that part of the American pathological love of the car is linked to the very real, albeit small, sense of autonomy that driving provides. Yes, the roads are often just blasted space between check points, but the sense of vision that driving provides is real.

Pat de Groot

These non spaces however reflect something inner as well. The interior non-space of the post modern citizen. The gaping maw or hole where the shrinking ‘self’ used to be is compulsively filled with electronic gadgets and activity, and programmed leisure time, and ‘entertainments’ of distraction, repeated at a hyper pace. Only in the inner landscape featuring deep cavities of a black nothingness, can the War Gods come to rule. The non-spaces shorn of history, and where every single wall is filled with advertising, is an ahistorical non-memory. You have nothing to remember, no relational history. Only the possibility to purchase. Buying is conquest. If I can buy that iPad, I can eventually buy a person to run it.

The corporate mainstream media today are like the town criers in their kitsch volkish villages for pagan war gods. The level of depravity that accepts the death of infants and children is hard to calculate. Most Americans defense of Israel is not an expression of love for Jews or Zionists, its a hatred of Arabs and Muslims. This is the culture you get when all that is left of Utopian dreams is Disneyworld and a trip to the Super Bowl, or the belief that maybe one day I can become like Donald Trump. The mind of today’s Israel is shaped by thugs, Avigdor Lieberman, the former Baku radio personality and Moldavan nightclub bouncer, turned racist demagogue leader of the Yisrael Beiteinu, a secular nationalist party, a man who at different times, has suggested bombing the Aswan Dam, Beirut, and Tehran, and asked for the expulsion of all Arabs from the Jewish State. The problem is that Lieberman is actually pretty much dead center on the Israeli political spectrum. Bibi Netanyahu, the also thuggish Prime Minister, a ruthless pitiless and crude man, whose vulgarity is only matched by his arrogance, no longer even pretends to struggle with questions of peace. Israel intends to implement the final act of its ethnic cleansing of Gaza and the West Bank. They care little for International sentiment (I mean as long as the Rolling Stones still perform in Tel Aviv, and Jay Z and his wife fraternize with these fascists http://blog.4ziononline.org/uncategorized/music-mogul-jay-z-invests-in-israel/#.U8U2Hvl_tA0) because they are the sub contracted goons for U.S. power moves in the region. They have immunity from any repercussions. They are much like the New Orleans police department after Katrina, or the Albuquerque PD all the time, or Sheriff Joe in Arizona. The U.S. media, Hollywood, has glamorized Israel for decades now. The very word ‘Mossad” is spoken in hushed tones.

Pilgrimage Church interior. Neviges Mariendom. Gottfried Bohm architect. 1963

The destruction of community, at both micro and macro levels leaves the individual in the role of outcast. In the era of global capital, everyone but the ruling elite is a scapegoat. The outcasts wander in search of survival. The culture of surveillance, where everyone must think like a criminal, where the only rewards offered are to be snitch or to shame someone else, has become institutionalized.

http://www.truthandaction.org/ny-dhs-will-pay-500-rat-fellow-citizens-buying-legal-goods/

In a sense the art of today that has value is that which demonstrates an integrity that defies consumerism and commodification. For this quality is the building block of community. It is important to think dialectically about this, however. The problem with almost all confessional art is that it privileges the creator in opposition to the group. The fact that an artwork becomes a commodity is really beside the point. The crucial factor is more in the potential for liberation that art provides, and that means liberation from the prevailing values of the Gods of War, the totalitarian and authoritarian vision that is most immediately traced back to Leni Reifenstahl.

Triumph of the Will. Leni Riefenstahl, dr. 1935

“Spontaneity is a relatively rare phenomenon in our culture” wrote Eric Fromm over fifty years ago. The cultic deification of the artist as seer is the shadow side of creativity. The valorizing of fake Shamans (Abromovic comes to mind, with her endless re-enactment of submission and obedience rituals as natural) and the constant reinforcing of conformist thought, of group-think, is all too prevalent. The best art is one that taps into lost memories, the real archaic traces of what has been forgotten. Again, of course, there is the imitation memory at work. The creation of false memories, where in a sense the entire culture is participating in a recovered memory show trial or 12 step intervention. There is a constant tendency toward breaking apart the group, and replacing it with a unified collective ‘self’, not a collective, but a collective mind of one. And now, with almost no community left, the struggle is to navigate through the resentments and pettiness of the privileged 20%. For as Reifenstahl said, the intelligentsia are the vanguard of conformity. Of adherence to the War Gods. The new Volkish primitivism might be electrified and computerized, but it serves the same purpose it always has. It is the idealization of an imagined primitive purity. It is self help and new age and organic tempeh burgers. It is the ideological means to actually ridding the world of the actual breathing people in those areas of privation and struggle. It is a false memory. How happy are the faces of those poor black village children. They have nothing, but they are so happy. Le Corbusier wanted to purify the eye but build toward equality, while Netanyahu wants to purify his country, period. So does David Duke, and so did Adolf Hitler.

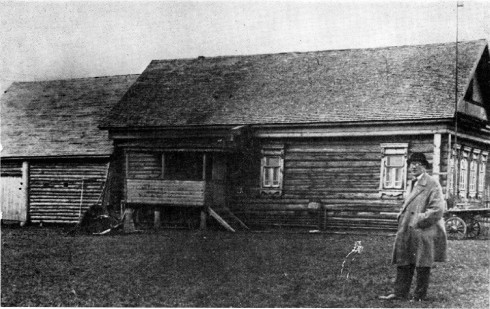

Le Corbusier, Russian peasant house, 1928.

The town center, as Jacques Goff suggested has been re-purposed as the re-ordering of time. This new sense of controlling time is critical to the experience of these non-places. I am reminded of what Adorno said of Kafka: “Only that {Kafka’s oblique perspective} allowed the writer to deal with a monstrousness that would have struck his prose dumb or driven it mad if he had looked it straight in the eye”. The horrors of this weeks assault on Gaza is beyond words, and even the graphic images of dead children is a crime too extreme to allow for conventional processing. In a letter to Benjamin, Adorno said the ‘web of space and time is incompatible with what is expressed in Kafka, and other great artists’. However, it is through them we are able to return to nightmare of fascist war Gods, to retrieve the memory of suffering. Barthes cited Kafka’s own comment in answer to a question about image, in which Kafka said “My stories are a way of shutting my eyes.” This is one of the paradoxes, or the negative dialectics of culture. There are several ways of not seeing. The mass culture that allows a form of numbness, of sleepwalking, and then there is the third eye, the one that sees most deeply when eyes are shut.

Akseli Gallen Kallela

You quote Michael Rojkind as he talks about designing spaces that are to address “the absence of expectation of programmatic control” (by which I think he means embracing and even enshrining the randomness of undesigned life, new ways for people to live together not as “families”, and life that has come about in unplanned and unregulated spaces.) In actuality, Rojkind’s design oeuvre is quite successful in being socially conscious and as sensitive to local culture and existing social structures as a big commercial architectural firm can be. He is saying that the norms of the institutions are often tone deaf to the needs and concerns of the regular people, poor or affluent, for spaces that are inclusive and humanizing; and that people have needs for friendly spaces that do not seek to control them and provide a welcoming and opening. The norm in most newly built spaces is non-human in scale(totalitarian intent) and privatized; surveilled, and oppressive, not to mention toxic; and planning access and egress especially for pedestrians is generally clumsy, inefficient and thoughtless.

Architects dream of physical structures that will express esthetic vision, enclose AND liberate, and are all irrepressible Utopians and optimists. I haven’t met or studied a single one who is not. (Except a friend’s father who designed prisons and was also part owner of what became a major S&L on the east coast.)

As for eradicating history: much as one may romanticize about slums and favelas being repositories of “history”, aren’t certain aspects of history—itself a fiction created mostly by privileged institutions—erased to the great benefit of human welfare? There is a history of defecating outside in India (big article about this in relation to childhood malnutrition in the NYT today). And the people in India, it is implied in the article, “like” to shit outside and walk around in feces as part of their culture!! Just like all those Muslim girls in Sub-Saharan Africa “like” to have their clitorises cut off, the ultimate act of cultural history.

But big positive social change—or lack of it–is in the hands of war gods as you say, and so people who dare to insist on Utopian visions will always need to struggle. The idea that failure is a given will never discourage the true Utopian.

@rita

Listen, i dont know what gave you the impression I wasnt supportive of Rojkind, because I am. I really like his firm and what they do. Which is why I quote him. What he describes is a criticism of most existing architecture and the disregard for what the reality is. I think you need to re read the quote and what i say following it. He works in Mexico City a lot, and most of his designs are quite good. And nobody is romanticizing slums, but the reality is that there are relations formed in even the poorest communities that are usually destroyed when slums are cleared….and slums are only cleared for economic development, not to improve the conditions of the poor who lived in them. So yes history is being destroyed when those areas are cleared. Not to say they shouldnt be cleaned up and social services improved etc. That all goes without saying. Still, the usual social improvement disregards the relations and human infrastructure of poor communities when they are cleared away. And they are then replaced with housing designs that totally ignore the needs of the people meant to live in them. Which……….is the point being made here. So yes, that tone deafness is all true……and its exactly what is true in other areas, other mediums of expression. Its strikingly similar in fact, the same tone deafness.

But additionally, no, not all architects dream of liberation or have utopian intentions. They may pay lip service to that, but usually the economic imperatives far outweigh real consideration of needs. Not that this is always the fault of the designers. Its the entire system of profit ……such large scale social planning, as those being discussed here, involve huge amounts of financing, and when that is the overriding concern, other matters become of little import.

To be clear. The Utopian designs in city planning are often quite good in certain ways…..thats where i started with this. They get blamed for failures that reside with government. There is a lot of bad architectural planning however, that i dont see as Utopian at all. But my point was that that project in Naples and its disintigration wasnt the fault of the design. At least not totally. The government abandoned the people, and no allowances were made for population density, which had been mis-projected, not to mention the crime syndicates and drug problems. Its just becoming clearer that fewer and fewer large social planning projects are really designed with social change in mind. And the failures in the past of many so called Utopian city plans is being laid at the feet of the architects and designers and it shouldnt be.

Speaking of utopian architecture and space… I wonder if a theatre is, de facto, a Utopian space. I was always fascinated by that aspect. I mean, like Peter Brook says, you can take any open space and call it a stage. It’s the only art that’s truly egalitarian — all can participate, all can watch, and you don’t need a special space — you only have to bring yourself. And no matter how much business interests try to commodify theatre, they’re never truly able to — they can try, but the only thing that actually gets commodified are the trappings: red velvet curtains, tip-up seats, glossy brochures, fancy sets, big name Hollywood actors; in short, the inessentials; what is essential (and austere) must remain untouched, because the performance and the act of watching can’t be commodified. That makes it different from film, I feel, because film can still be commodified to its core: its key material is the juxtaposition of images, and that juxtaposition of images is used all the time in advertising and MTV, so much so that the current generation of Hollywood directors all come out of MTV. But theatre can’t be colonized the same way — you just can’t do an advertisement in live theatre. If you do, it becomes something else. The reenactment of the function of a town-crier, perhaps. But it’s no longer commodity.

So maybe by definition theatre HAS to be a utopian space? By definition? ALso, what do you think of the various ways that you can seat an audience, besides the conventional layouts of theatres? I feel like there is a lot of untapped potential in the interaction between architecture and playhouses, somehow…

@Exir,

I don’t know about what you’re saying, Exir. I mean, I’d like to believe it, but I think that it is pretty rare to see theatre that isn’t commodified—at least what I’ve seen in North America. I think it is possible to build theatre spaces that are “non-places.” I also think that both those producing the “theatre” and those watching it, are becoming more and more capable of willfully ignoring history in space. This ‘history in space’ is something which I believe creates a certain presence in emptiness, that can give one a sort of chill. I sometimes worry that people are becoming immune to being moved by a space, or by another body moving in a space.

I’m still having trouble with the word “utopia.” It isn’t a word I ever really use. I guess utopia in theatre to me would be the ability to be moved by watching a body moving in space… Utopian because it is beautiful to see a body moving in space and time while it is also heart wrenchingly clear that they/we are dying. Theatre is so different from film that way in that it can open us to experiencing the impossibility of being alive when death is immanent. (Er… and when I use the words “alive” and “death,” I do so with the realization that I have a sort of complicated understanding of what those terms might mean and contain. So, in short, I mean something a bit more complicated than being in the coffin or out of the coffin… but of course, I mean that too…)

I also wonder about space in theatre. It seems to me that there are several spaces in operation. What are the cultural expectations and politics of a conventional theatre space? I think some people might fear that these spaces can be authoritarian (proscenium stages), but I also wonder if–when a play really starts to work—if that authoritarian sensibility begins to break down. What is there to say about a certain striving for emptiness in building a space for theatre productions? I mean, creating a space within which other spaces/places might exist? I think that spaces can haunt us. What about the character haunted by a space? How might that space exist within the physical architecture of the theatre? How might traces of it exist or be extinguished long after the production has been played out?

As to various ways to seat an audience besides the conventional layouts of theatre… well, I’ve seen audience arrangements done many, many different ways. I think there can be value in re-thinking audience-performer orientation; however, I think that it is relatively rare for theatre practioners dabbling in re-configurations of spectator to action to really ask themselves WHY they are doing it. Sometimes the piece requires a new configuration and this can be powerful, but I think we must be careful that if we re-configure the audience, we are constantly asking and re-asking what purpose this has for the piece. How does it serve the piece? Are we just doing this because it is “cool” or different? What sort of disruption are we creating in audience expectation? Is that disruption serving the piece? The space? I really do think that audience orientation is powerful, but it think it depends on the context of the production in question as to how it is done and whether or not it is useful.

@ Steppling

I could probably contemplate for a long time on much of what you have offered here. Thinking especially about North American car culture in what you say here: “I suspect that part of the American pathological love of the car is linked to the very real, albeit small, sense of autonomy that driving provides.” I do wonder though, if that autonomy is not just “small,” but false…?

I’ve been in a bit of a rage these days about how limited my freedom is if I decide to buy into car culture. I try to explain to my co-workers and people around me that I want to live somewhere with access to public transit, or at least a city where I can walk wherever I need to go. Otherwise, I am a slave to car culture, and I will even need to work more hours at some horrible minimum wage job, just to afford the car, insurance, parking, gas, maintenance–and then, I might be working so much that I won’t really have time to drive anywhere anymore… Not to mention that having a car is socially and environmentally destructive. I don’t want my “autonomy,” however small, to exist on the basis of someone else’s oppression.

I was talking to a girl about train systems at work and she told me that she would never use public transit because it is too dirty and “people pee on buses.” I was really upset by this comment. And again, it ties into some of your thoughts on hygiene and cleanliness and class consciousness. I mean, I was shaken by how she spoke about people that use buses. I just… I mean… there are REAL people on the bus! And this kid wants to go to school for nursing…!

Eh, I guess all I can say is, “good luck dealing with the pee during your nursing career!” Astounding.

But you’re right. I’m near LA in the Inland Empire right now — a.k.a. the most hostile desert for pedestrians anywhere in the world. I have to admit, like a desert, it does have its cold and austere beauty to it, especially at night with the lights on, but it is also pretty hostile, in a sense, to everyone who doesn’t have a car. The “autonomy” one gets by having a car is complemented by the removal of all true autonomy in the space around you, because building the perfect “car-friendly” space necessary to allow car-autonomy (which is the entire philosophy of city planning here, it seems to me) must, inevitably, involve the very kind of space usage that reduces people-autonomy when you’re not in cars. The car-autonomy is literally built on the foundation of the sacrifice of people-autonomy in a natural, humane, communal relationship with the environment. There is no community space: the space becomes a collection of atomized destinations, almost, or terminal stations… which you pass, either in your metal container or by yourself… but there’s no space BETWEEN terminal stations. The journey from one destination to another is connected by an interim where you’re suspended in a void, in a long holding-of-breath. I dunno, that’s the best way I can describe my visceral, physical feelings as an outsider who used to live in a city where I can walk everywhere.

@all of you above:

There is really a lot of excellent thoughts here.

Let me try to touch on a few of them. First calla……the question of car culture is huge…i mean its a huge huge topic. I grew up in southern california. I grew up in the center of car culture in the world. So…i just say that by way of preface. Now….yes on one level its an illusory autonomy. But before i answer that, the environmental aspect….choosing to drive a car or not is not an option for the poor. Many people cant afford cars, and others HAVE to drive to make a living. Those driving cars are not really the problem. But…putting that aside for a second; there is something connected, in whatever fragile way, to an experience of freedom when driving. Ive driven all over the world. Across europe, across the US several times. I have always felt a certain sense of escape in these experiences. Its not really escape, but the experience provides a certain poetry of movement. And access to places often hard to get to. Train travel has its own poetry, and i love train travel. I traveled across the US and Europe and India by train. Its always its own sort of wonderful experience. One can read on trains for one thing. So Im speaking in a sense about aesthetics. The horizon, the way space is ordered when in movement. Walking has its own poetics too. I love walking. But growing up in LA, as exir pointed out, the pedestrian is truly an outcast. And vulnerable.

And yes, of course, to the economic oppression of needing a car.

When i first came to europe, i was in Paris, and i remember the liberating sense of not *needing* a car.

I do think however, that in certain contexts the car has afforded a kind of creative construction of cognitive mapping, and i think its important to recognize that. Im not even sure why.

But theatre………this is something I have spent most of my adult life contemplating. And ive written a lot about it (read my dialogue with molly klein in the archives here)…..because i think jan kott when he wrote about King Lear and Beckett, in that famous essay of his, touched on something very significant. Peter Brook’s The Empty Space did too, as did Herbert Blau in Blooded Thought, and Artaud. Theatre space, the empty stage, is a ritualistic space, a ceremonial space, and it only exists in a dialectical relationship with the off stage. Ive always said the stage was the ego, and off stage the Id. The best plays always take place off stage. Now molly said something sort of important when she was interviewing me…..and that is that there is a sort of aperture in which one can become the other…..sometimes. In greek tragedy the messenger comes from off stage ……the action is off stage. Its true in a different way in Shakespeare, too. Because the play is impossible. I wrote about that here too, in a posting called The Impossible Playwright. Its ever more important in a way because of the ascension of film culture. There is no offstage in film. Certain directors construct an approximation of offstage…Pasolini does…Fassbinder did think, and Mizoguchi perhaps. Antonioni too. But however these strategies are employed, the theatre remains unique. But of course, yes, yes yes yes theatre has been co-opted largely. It has been in the business of, exactly, destroying the ritual (and at times replacing it with a kitsch ritual). And narrative intersects here, as well. The enclosing of the tragic potential takes place in several registers….narrative, performative, and even in the physical location — which impacts the sense of audience and attention. All of this is to say that the potential in theatre remains vast. Ideally, it is a more radical art form than film, or probably anything else. Blau said even in theatres where there is no curtain, the theatre remembers that a curtain was once there.

But you, calla, said something else very interesting. And that is this idea of audiences having lost the capacity to watch, to experience bodies in space, on stage. I see the degrading of acting, too. Its very hard to find actors willing to risk something….actors not turned into automatons , whose gestures and physical presence is not mediated somehow. Everything is designed now to kill off the emancipatory aspect of live performance. Ive always hated performance art, or monologues, or whatever…..the one man show….because i feel its not theatre. Its closer to a sermon or something. There is still something very meaningful in an empty stage space, and in that moment when a play *begins*. Something has escaped the stage at that instant and the play pursues it until it recognizes it cannot catch it……and it is that moment that melancholy or even the tragic takes place. All plays that are any good must be melancholy. What is it that has fled? Well, thats a whole several volume discussion, but its what calasso talks about, that fleeting sense of something we have forgotten. The real memory we have, and have forgotten. And if not we, not the individual, then we the species. Theatre is allegorical. To really be theatre.

there is a good deal more to say here…..so i will return.

First, on Cars

Exir, I hear what you’re saying about how the existence of car culture reduces the availability of a community space, or a place where people can connect with the environment… and also what you say about there being “no space BETWEEN terminal stations.” Although I see what you mean, I am not sure that these issues are the most dangerous part of car culture, as long as there is always the option of walking, or biking, or busing, etc. I guess I am more wary about the incredible resources required in order to produce, ship, sell, and maintain cars and car infrastructure. This includes political and cultural resources.

As for the “in-between” spaces in transit, I think that there is A LOT to be said here. I actually did a fair amount of what might be called “ethnographic” research, and “skytrain poetry” on the space of public transit (light, high-speed rail in this case). I have a lot of unanswered questions about that research, and I think some of them could apply equally to car travel too. One question is that of space—i.e. what is the space of the train—is it everything in the train car, or does it include what you see out the window? And what can we know about a building, or a tree, say by passing it by quickly from afar, or pausing in our walk to inspect the texture of its trunk up close? A different orientation, but perhaps, no less valid?

And on to Steppling’s thoughts:

I think it is okay to like driving, and I do understand that feeling of autonomy and freedom when driving, but I still think that it is… well, maybe I’m just paranoid, but I still feel that my autonomy is outweighed by the sense that it is an illusion. As for my personal context with cars, I have a license and do borrow people’s cars to drive; however, I do not own a car and do not foresee this being possible or desirable anytime soon. I live in a small town with no public transit or car sharing service, and a heavy reliance on cars to get anywhere. I have spent a few years living in cities with public transit, or where things were close enough to walk to—nowhere as big and bright as LA though… Anyway, I hear what you are saying that some people can’t afford to have cars, and that others must have cars in order to work (in a way, I fall into both of these categories). But don’t these very facts support the notion of an economic/social enslavement to vehicles? (I guess you haven’t really denied this possibility in your response, I just happen to be stuck on this point).

That the “car has afforded a kind of creative construction of cognitive mapping,” is, I think, a valid statement, if I understand it correctly… (not sure if I do). But don’t you think it is true to recognize this creative construction of cognitive mapping through various other modes of transit, spatial orientation, and action? Like you say, there is a particular poetry of movement, of train travel, and of walking, and I would say there is a kind of poetry to car travel too. But the problem I feel is this enslavement to owning a car. I probably COULD own a car, but I would have to do too much stuff that I don’t agree with, or don’t want to do in order to own it. Also—there’s the trouble with the architecture of a car—of how you have to Sit. They’re physically restrictive spaces—this may sound trite, but I think it is really important—when you are driving, the configuration of your body is limited. I mean this in a Grotowskian sort of way—that our bodies ARE inextricably our emotions, our psychology… What does the car do to my body? What does it do to the bodies of people who manufacture car parts all day? Does this have anything to do with “creative construction of cognitive mapping…?”

Next, on Theatre

Have read some other dialogues on here, but not the Molly Klein one yet. Will read it before I comment further (if I sense that further comment on my part is necessary…).

When I say Theatre can’t be fully commodified, I don’t mean that business interests haven’t already commodified much of commercial theatre within an inch of its life. What I mean is that the *core materials* of theatre can’t be commodified and by definition must evade commodification. That sets it apart from other forms of art: for example, when the visual arts is commodified, it borrows a vocabulary from advertisement and such which *actually uses the same raw materials* as the visual arts. Same with movies: advertisements and MTV uses the exact same raw material as a movie, which is images and sound juxtaposed using cuts. But whatever business interests try to do with commodifying theatre *can’t* use the same material that constitutes theatre. They can only commodify the periphery, as it were. Now I do agree that ways of seeing, and ways of engaging with space, can be colonized. People perceive in a commodified way, as it were. But it’s different, somehow…

quickly…..but i hope to expand on this later……….but I think, Exir, yes, that one of the reasons theatre exists as a marginal medium now is because it so resists commodification. Sure, Cats or Les Miserables…etc…broadway…..is a commodity, but then it barely can be called theatre. As I said above, the turn in theatre has had the effect, exactly, of erasing the things make theatre unique. Broadway is imitation cinema. Or often TV. The entire style and narrative of much theatre, most theatre today, is borrowed from TV film and madison ave. Its just sentimental, or silly, or jingoistic…….and usually it erases the off stage. The entire idea of doors on stage is something I am sure must have arrived in the 19th century. I dont know, i have to look that up, but a door doesnt belong on stage. The stage space itself is a door.

So, yes, theatre is today about 99% awful commodity junk. But….theatre itself , when allowed to be practiced, remains the most radical of mediums.

Exir,

Thanks for clarifying what you mean about commodification and theatre.

On Theatre,

So, I read the first two dialogues with Molly Klein. As I suspected, I am a bit… uncertain as to what I can say. Those dialogues are quite rich. I mean, I could contemplate forever several of the ideas/images both of you bring up: narrative, space, audience, x-rays, MRI machines, records, childhood photographs, absence, pre/sub/unconscious, on/offstage, the forgotten…

Reading this makes me remember a lot of things.

On Acting

Steppling, you said in your comment, “And that is this idea of audiences having lost the capacity to watch, to experience bodies in space, on stage. I see the degrading of acting, too. Its very hard to find actors willing to risk something….actors not turned into automatons , whose gestures and physical presence is not mediated somehow. ”

I have a question about this (for anyone). Have you ever seen… or, maybe, do you know what happens to an actor who takes this risk but they… FUCK! I can’t figure out how to say it!

(very long pause)

Okay. let me try again… What are the conditions necessary for risk to take place?

Or,

Can theatrical risk ever happen alone, or must it always happen in relation to the other?

Or, maybe this gets at it better…

How is the actor to deal with the shame of believing in an audience, and then the uncertainty of realizing that the audience did not see, or might not have seen the shame, the beauty… the existential struggle… the impossibility of the actor’s reaching out to pick up that glass of water…? I mean, here is the actor, reading the stage directions that say something like, “picks up the glass of water,” and the actor is thinking, ‘I can’t do that.’ But, they have to do it, anyway. Is acting somehow about the impossibility of acting?

that’s all I can say right now.

@calla………..its really much more complex than this. If you go back to Kanter and polish theatre in the 80s, you saw this remarkable level of commitment from actors. And then you see it in Peter Brook’s companies. But they have created a context, and you have to do that and its the single most important thing required for significant theatre and the single hardest to do. I know, Ive failed at it a number of times. I think i created very good theatre…..i do, but i also was far from satisfied in the end. And part of it was that i felt mediated by a system, by ticket sales and marketing and PR. Its very hard, and to think about keeping a handful of actors around, making chump change, for a decade…well, today its impossible. When I did The Shaper in LA, in 1985…….we sold out, SOLD OUT, for six months. Thats impossible today. When I think back, i wonder at how that was possible. The Padua festival, which i was part of for 14 years, is impossible today. So its a very complex thing. Read that Herbert Blau book because he addresses some of this. The brook is great, but it was written fifty years ago.

Alright, I think I can get my hands on the Herbert Blau (incidentally, it is located in a library an hours DRIVE from here). I have read Brook ages ago, so could brush up on him too. My most recent examinations of acting have been Grotowski based.

I may or may not know what you meant about “creating a context.” Sometimes I know or understand things but don’t articulate ideas in the same way as other people because I discovered the ideas through different vocabularies or experiences. I can’t comment either way about this ‘creating of context’ being “the single most important thing” or the “hardest thing to do.” I mean, I don’t know how one could do anything meaningful without a context or awareness of context but I’m not sure that’s the entirety of what you’re referring to here.

As for “commitment” in actors–or any sort of artist–that is another huge topic. I think this is directly linked with the question of “risk.” I mean, on a very basic level, it is appalling how many actors come late to rehearsal, or don’t learn their lines, but even when they do devote many hours in the rehearsal room (even for no monetary reward), there is sometimes a lack of curiosity there, or a decision to resign oneself to boredom rather than to explore it. For most wage labour jobs today, all that is required is one’s time; the theatre requires one’s soul. Back to Exir’s comments about commodification of theatre… we’ve got zombie theatre today…

I concede that all of this is extremely complicated which, in part, is why I am frustrated about trying to articulate the complexities here; I can’t find a way of doing justice to these problems/questions of art, theatre, acting, humanity… I mean, the internet is great for finding people who are asking interesting questions, but I’m ambivalent about how to use the medium. And then I wonder if I would say as much by just not saying–but that’s the thing about the internet, and blog posts and forums—there’s a limit to what we cannot say.