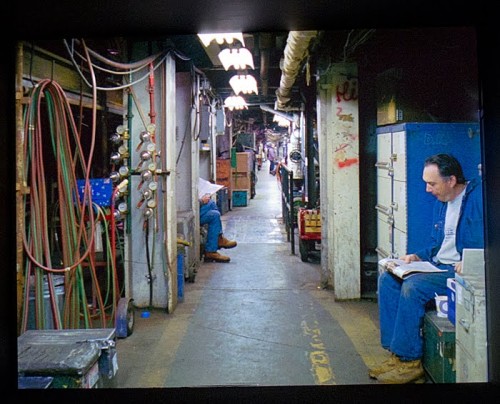

Per Bak Jensen, photography.

“‘Yugen’ as a concept refers to mystery and depth. ‘Yu’ means dimness, shadow filled, and ‘gen’ means darkness. It comes from a Chinese term ‘you xuan’ which meant something too deep either to comprehend or even to see.”

Donald Richie

A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

Philip K. Dick

“The soberest conclusion that we could make about what has actually been taking place on the planet about three billion years is that it is being turned into a vast pit of fertilizer. But the sun distracts our attention, always baking the blood dry, making things grow over it, and with its warmth giving the hope that comes with the organism’s comfort and expansiveness.”

Ernest Becker

With the rise of Capitalism, the Industrial Revolution, and the Imperialist project that accompanied this, western consciousness took stark turns away from that of the rest of the world, and from its own earlier history. Aesthetically this is most obvious in architecture, or at least the interiors of homes.

Beatriz Colomina has an essay; The Split Wall, Domestic Voyeurism, in which she examines the vastly underappreciated Adolf Loos and his interiors, but also the idea of the home as another expression of this new basic point of view of control. In Loos, the window was always opaque, or situated so furniture, such as a couch, was situated beneath it. The window was to let in light, not to look out. The eye is turned inward in Loos, and really in most Bauhaus interiors as well.

Moholy-Nagy home, Bauhaus, Dessau.

In a sense, it is the detective novel. It is the re-enacting of crime. It is the originary guilt story. But part of the mystery is the unseen story of domination. The impossibility of escape. Nature was not the primary enemy, but the creeping powers of control by the state. Fascism, in a sense, had begun to the enter the dreams of mankind.

Colomina makes an interesting observation, though one I might contest partly. She writes; “In Loos’ interiors, one is given the impression someone is about to enter, in LeCorbusier’s the impression is that somebody was just there.” So the drama, the theatre narrative has shifted. I think this is true, but I would view it somewhat differently. The detective, the viewer of the interior is now chasing someone, as Colomina observes, but I see this as less as a detective searching for clues as I see the site of societal control exercising security checks. The detective is not exactly a detective. Now Le Corbusier I think is often misread, and I’m not sure that his demand for transparency was driven by what critics usually ascribe to him. For Corbusier the home was the seat of a movie, not a novel.

John Divola

The drama is always unsettling, which is partly the missing ingredient here. But Colomina is correct when she points out the inhabitant is more actor now, more film actor. But we are always actors, as Shakespeare well knew, the only change was the kind of play, and the evolution into film. I wonder if, in one way, the work of certain architects today does not become TV more than film. The interior of houses reflect the set up of a 3 camera sit-com. Desi Arnez as architect of domestic dwelling. The rise of the tract home post WW2 was a televised dwelling. It was an ideological architecture of banality, and of propaganda, and it was gendered as well. The house with a garage for the car was calibrated for a world of pre-ordained destinations. If the windows framed an outside world, it was as a TV screen. Additionally there were sliding glass doors, and other prefabrication methods, which seemed to go along with the prefabricated neighbourhoods of post WW2 America. The home was the site of a half hour sit-com, and work space was the site of drama. The office and factory became the defining space for psychological narratives of patriarchy, and the home was a gendered environment that, in a way, had erased, or tried to erase, narrative. This is the Disneyfication of American dreaming. The rise of a kitsch sense of space in which increasingly trivial mental stories are played out. Never mind these are not the actual stories of daily life. Never mind that control was inscribed on all private spaces, as well as public space. The glass doors, the picture windows, implied a view that didn’t really exist.

Deception, 1946, Irving Rapper dr. Anton Grot set design.

Out of the Past, 1947, Jacques Tourneur dr.

The spaces of domestic life in the houses of the West are produced less by architects than by the entire culture industry system of image control. Architects are responding to the same style codes as the people living in the houses. Still, class intersects here. The corporate building industry responded a bit differently than people buying, or certainly renting the post war house. The archaic traces of the monastery one feels in Loos or Bauhaus work is gone by WW2. Suddenly decoration became a defining aspect of class, and of ideology. But there is something else that can be found in narrative, and that is the idea of memory. And memory is linked to our mimetic re-narrating of space. This is what theatre is, and what film is not.

When remarking on the idea of transparancy in architecture, Benjamin said; “Discretion concerning one’s own existence, once an aristocratic virtue, has become more and more an affair of petit bourgeois parvenues.”What was the modern middle class owning exactly when it bought a house? Like the American suburbs in which the working poor move, by economic necessity, there is no community memory and hence the tendency to create faux memories to fill in the empty spaces. The role of transparency, I think, has been talked about in the wrong way. Nothing is really transparent for one thing. Architectural transparency inscribes the opaque, and reflectivity. The post modern urban landscape is not one of just fear and control, but also one of anxiety. The shiny facade reflects back your own image. One is stalking oneself. One may fear the police and CCTV, but the tensions of amorphism and the sense of there being only surface, have created urban spaces that kill off mimetic reading. They are anxious space. The interiors of apartments and houses are narrated by owners or renters along the lines of shopping. I got this last year, and oh, over there is the couch we bought on sale in Delaware, etc.Never has so much useless non essential junk filled up living space.

Kirk Lybecker

The ideological aspects of architectural transparency immediately bring to mind Freud, and Lacan both. The mirroring effect and our estrangement from ourselves. The inside becomes the outside, and vice versa, according to Freud on the Uncanny, and space then, in these landscapes of anxiety and alienation, transform into depthless surface barriers to inner life. And this in turn brings us back to Adorno on depth. It also touches upon control in another way. Leisure time was accompanied by the buying of recreational commodities. The post war American house is consumed with ‘stuff’. The very idea of clutter, I think, must be American. The tendency to accumulation of junk is a kind of covering over of uncertainty.

“…the sphere of immediacy that we are all concerned with in the first instance, and which we are accordingly tempted to regard as a matter of absolute certainty, is actually the realm of the mediated, the derived, and the merely apparent, and hence of uncertainty.”

Adorno

But this is a necessary illusion in a sense, as Adorno points out, that society produces the contents of our minds, while at the same time ensuring we are blind to the fact of mediation. The post industrial hyper branded landscape is always in the process of covering up, and often covers up by pretending to lay bare.

It is this false simplicity, which in architecture is often brutalist or even minimalist, seems by its nature to parenthesize ‘effects’, in an effort to communicate its own message. This is a culture of ‘effects’, a hallmark of advertising, and the facades of many post modern buildings are like the faces of poorly trained mimes, forever pretending to a generic ‘idea’ of neutrality, but in fact are presenting something closer to the un-rented billboard, a palimpsest of earlier manipulative messages, now forgotten or interrupted.

Sharon Lockhart, photography.

It is important to remember, given the state of new age pop psychology, that to simply retreat from the world does not equate to depth, or a deepest knowledge of the foundations of the universe. Adorno repeated this several times in his notes for his lectures on Negative Dialectics. Only by intellectual and aesthetic opposition to the ‘sheer power of the existing state of affairs’ that erect the ‘facades that resist the incursions of our minds’ can we provide a non ideological meaning to our ideas. Philosophy is the search for the right expression (Hegel). And so, in aesthetics, is to be found the expressions of thought that extend beyond what we can systematically grasp. But rigour and expression are not mutually exclusive. No philosopher is not also a great writer. So it is in art. No convincing artwork is without rigour and there is no rigour without, first, the material world. The rigour of expression, in language and in image is the ground zero of mimesis. There are dangers in rigour, too. There is a lurking authoritarian dimension to rigour that is akin to discipline.

Leave it To Beaver, CBS TV, 1957-1963

So, to return to the modern house, and today’s fortress city, and to the layers of commodified kitsch bric a brac that occlude an engagement with space, the untruth of surface is part of a psychological fortress. Post WW2 saw a boom in planned suburban communities. There was the representation on TV, in film, in magazines, of younger white couples buying their own (detached stand alone) pre-fab tract homes as part of a manufactured myth of the American dream. It was Norman Rockwell-like, and was reinforced with Boy Scout troops, PTA meetings, and the assorted new necessities of middle class life (lawnmowers, dish washers, etc). These new commodity fixations existed in an architecture of planned banality. But of a specific sort; the sliding glass doors, the picture window, the back yard, and the loss of attics and basements, replaced with the auto-pegged garage. There was a horizontal emphasis. There was also a slightly schizophrenic dimension to notions of private and public. There is a lot written about the rise of plate glass and the intentional blurring of inside and outside. While this may have been the intention, it was, I suspect, subsumed by several other factors. One was the racial red-lining that kept the ‘burbs white. But not just white, for the secondary aim of these communities was to cleanse these new communities of urban dirt, both real, psychological, and ideological. No communists in suburbia (was part of the idea). No crude immigrant dialects, no moral lassitude, no class antagonism. The rise of TV played no small part in this, and the screen as center of private family life became a fixed paradigm. The representation of immigrant city life rarely included TVs, but in the images of suburbia everyone had TVs. And they all had cars. And there was a defined role assigned to each gender. But especially for women. And the culture industry focused enormous energy on creating iconic ‘housewives’ as characters, as well as creating daytime shows targeting female audiences (Queen for a Day, etc). And narrative began to focus on certain structural elements; the episodic quality was usually also folksy in tone, the stuff one chatted about over the back yard fence. Ozzie and Harriet, Father Knows Best, Leave it to Beaver, Burns & Allen, etc etc. There were certainly contradictions in all this, for I Love Lucy featured a Cuban musician in Desi Arnez, and there was no shortage of Jewish actors, many veterans of vaudeville. But the germane point here is the intentional shaping of narrative to reinforce certain values. The values of patriotism, family, wholesome recreations (this was the time of the selling of the idea of vacation and films relfected it), and marriage. The values that increasingly were, noticeably so, absent in people’s actual daily lives.

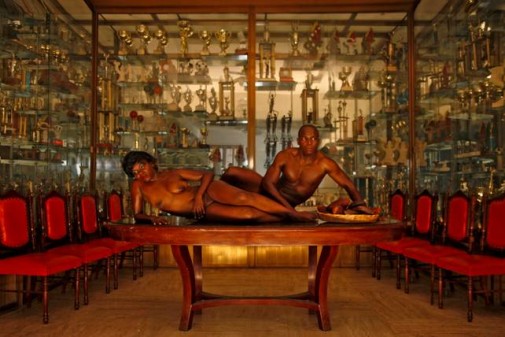

Philip Pearlstein

The rather rapid erosion of pre fab suburbs was one of the first massive contradictions in how life was portrayed by Hollywood. Nobody lived like Father Knows Best. Husbands didn’t wear ties to the dinner table. People drank, cheated on their spouses, and beat their children, children who were living in culturally arid landscapes of almost planned boredom and vacuity. The HUAC hearings, the hysterical drive of government paranoia and the growth of very consciously constructed programs of control for a populace not performing as Ozzie and Harriet did, layered the entire post war decade as one of cognitive dissonance, of white America’s first panic attack. And it was also the decade that gave birth to exponential growth in marketing and advertising. Doris Day and Rock Hudson in Man’s Favorite Sport sort of ecapsulated an idealized white dream, the accumulated signifiers of the earlier decade all wrapped up into one strangely creepy Howard Hawks comedy. Of course there were multiple narrative and marketing lines in all this. The Ozzie and Harriet vision was middle class, at least largely, and others, like Sirk, were commenting on the emotional horror of bourgeois pretension; and this included the Ayn Rand psychotic ideal of callus Darwinian personal superman fascism. Throughout, it is interesting to compare the decades of the second republic in France, in Hausmann’s projects for Paris, and the reinventing of the American suburbs after WW2. A specious comparison for many reasons, except for one point, and that is that the sense of living space, the scale of apartment life, the actual social sensibility of the French builders is antithetical to the coercive distillation of duty to authority, and the psychically divested sense of life in most of planned suburbia. The conformity and repetition. Just compare the French door to the front doors of most mid century American houses. In one, the door is expansive, larger than life size, and possesses something of grandeur, and even a certain sound of warmth. In the other, the door is pinched, and too small for more than one to enter, and yet pitched to evoke nothing so much as an resentful scowl. Architectural neurasthenia. It is here, too, that the role of the automobile enters the discussion. The xenophobic American provincialism one still feels is connected to the constant selling of jingoistic propaganda about foreigners. The car culture fostered, further, a sense of personal isolation. A man and his horse became a man and his Chevy, or Cadillac. Where Hausmann’s wide boulevards allowed for increased height in those neo classical Parisian buildings, and more living space, the wider auto friendly streets of America created more space *between* people. Between people and between classes.

Alexander Apostol photography.

The grid has certainly been written about as a defining characteristic of how urban space is perceived, but I suspect that if one looks today at the DiStijl architects, one is more conscious of the human than the dualistic construct imagined by Rosalind Krauss. My point is that for American builders and city planners, the house was a de facto tomb, and the suburbs a containment encampment. For Lacan (and it precisely here that 2nd generation Lacanians wildly mis read his texts) the schizogrphy was evidence of a disorder, not an imaginary mystical design principle (ala Peter Eisenmen or Coop Himmelblau, or Koolhaas, et al.). The designing of American cities and suburbs has expressed something morbid and psychologically regressive. It has created denuded spaces where only cars can travel, through an open barren terrain, unprotected from sun and rain, and the increase in homeless-hostile design is only, really, an extension of currents already in existence. The drive was from home to market or mall, but really, it was emotionally from checkpoint to checkpoint, and through a no-man’s land. The space, the manufactured space of white america has always felt emotionally inert, frigid and stoic. For this is the real narrative of white america. And you see it in the return of the privileged hipster to the city, to displace again the poor and working poor, minorities and the vulnerable. White flight didnt work out, lets go back to the urban core, which feels increasingly humanized because of the actual life that exists there. The American house, from mid century onward, with some rare exceptions (like Krisel, Frey, Neutra etc) were conformist colorless voids, built on a scale that was experienced as suffocating, and with materials going out to the lowest bidder. My personal memories of childhood, of being very poor and on welfare often was of things not working. Nothing worked. Windows didn’t work, shower heads broke, garden hoses leaked, and floors got mildew. The paint peeled and basements grew fungus. The home as tomb and petri dish. Anthony Vidier points out, the ‘idea’ of home as somehow comforting was actually “At once the refuge of inevitably unfulfulled desire and the potential crypt of living burial, the womb-house offered little solace to daily life”.

Detail, Palace of Music, Barcelona. Lluis Domenech i Montener architect

This is the haunting of America, in a sense. And it suggests interesting ways to see technology intersecting, going back even to Mary Shelley and Charles Maturin, and onto the computer brain, from automata and marionettes to a model of the human brain as just software of some variety or other. There are dozens of associations one can make vis a vis the house and the human body. The Catalan movement associated with Gaudi, Montenar, and Modernisme Català, or the Glasgow Style, and assorted Jugendstil architects such as Odon Lechner, Karoly Kos, and Gustave Strauven, and within all these threads, some more and some less dialectical, there is a tension that creates that sense of ambiguity to the Industrial Revolution. There was a sensuality that spoke to delirium as well as suffering running throughout. By post WW2, in the U.S., something else had happened. Nothing ever travelled west from the cities of Europe, whether Barcelona, Glasgow, Ghent, or Prague, that wasn’t homogenized somehow when it arrived in the U.S.

A distillation of the same Calvinist punitive mind set that pushed along Manifest Destiny, and participated in the slave trade, was the same psychic structure that would deny darkness ever exists anywhere. The suburban tract home is the very essence of denial.

Finally, the Disney fantasy was not true. Rockewell was not true. The disturbing darkness of Hopper and Ault and Sheeler was far closer to the psychic core of U.S. society.

Walter de Maria

And a final note on film:

This last year or two, there have literally been only three films (that I’ve seen, and I see a lot) that I thought deserved mention. One was Blue Caprice, a Dostoyevskian re-telling of the DC sniper story. The criminally neglected second film by Irish husband and wife team Joe Lawlor and Christine Malloy, Mister John, with a brilliant central performance by Aiden Guillen, and now Stranger by the Lake (L’Inconnu du Lac), written and directed by Alain Guiraudie. An eerie mesmerizing study of sexual intoxication, and the fatal implications of today’s addiction to the manufacturing of identity. Critic Michał Oleszczyk wrote:

“Guiraudie’s directorial assurance is stunning: the entire movie is a master class in audiovisual storytelling, as well as an exemplary case of immersing the viewer in an environment.”

The environment is a gay cruising beach at a small French lake. It follows for ten days in summer a small circle of men, one of whom is a killer. It is sexually explicit (very) and there is a great deal of male nudity, but one, in a sense, doesn’t really notice this because there is such an acute and precise sense of character, and in the pared down mystery, which is no mystery at all, really, the subject of the film is a kind of blindness brought on by vanity, and more, by desire. The greatest achievement of this film is the clarity with which sexual lust is presented, and the ways in which sex is fetishized, and linked, for some, to violence. It is a remarkable film. Jonathan Romney, at Film Comment, wrote of Guiraudie and Stranger at the Lake:

“The film, his first to receive a U.S. release, represents a fascinating new development from a very individual figure in French cinema—a professed militant and member of France’s Communist Party, an eclectic cinephile whose influences include Straub-Huillet, Samuel Fuller, and Tintin comics, and a director who, over some 20 years, has created an imaginative universe entirely his own.”

Stranger at the Lake, 2013, Alain Guiraudie dr.

On the subject of film, have you seen Neighboring Sounds, a Brazilian film that came out a couple of years ago? I haven’t seen it, but based on the description I’ve read it seems like it deals with some of the same topics as your last few postings. The fortress city, middle/upper class spaces, etc.

Great article, touching on a lot of points that I’ve felt when I was walking around in American suburbs. It’s so pervasive and so invisible, the way the space controls behavior and restricts them to a narrow range. There literally isn’t any space where you can do anything — the proportions are all wrong.

This, BTW:

“The post modern urban landscape is not one of just fear and control, but also one of anxiety. The shiny facade reflects back your own image. One is stalking oneself. One may fear the police and CCTV, but the tensions of amorphism and the sense of there being only surface, have created urban spaces that kill off mimetic reading. They are anxious space.”

reminded me of an excellent piece of music by the band Arcade Fire.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6iHk6f6vvS4

Also, if you’re interested, their album “The Suburbs” is quite excellent as a whole, and they treat similar topics to what you’ve addressed here.

This piece addresses the deterioration and disfunction of what was actually a utopian idea, radical in its inception at the time, and like most utopian ideas, destined for failure. …Just to cite a couple of examples…The New Deal proposed planned communities, the first of which was built near where I grew up: Greenbelt Maryland. It was a planned village–suburban– around a lake, parkland, with apartment buildings, duplexes, single family homes, and a community center (with a big socialist realist mural). The idea was to have a mixture of different social classes. The apartments had black floors as I remember (a friend lived in one) and were almost brutalist in design, and were very spartan about amenities. The duplexes, mean for families, had common backyard spaces with the streets flanking the houses, so there was green space that was to be shared and not fenced accessible to all the residents. But most development was “unplanned” and zoning almost as bad as Los Angeles. It was the late fifties when out suburbs started to see the Levittowns…as in Bowie Maryland, horrifying, banal and barren. By the sixties in Greenbelt, of course, many more single family houses within view of the lake were built –beyond the means of most folks. As the 60s boom in government spending (on the Vietnam war) affected D.C., more upscale planned communities, along the Greenbelt model but NOT, went up close by, like Columbia, Md….and of course there was a racial dimension to all this development, as D.C. was 70% African American from the South.

…Neutra, whom you cite as an exception of sorts, based his architecture on a theory of health which held that by having light and easy access to “nature”, i.e. the outdoors, people would have better physical health. The sliding glass door was built to that end. This past weekend I sat on the meadow in Silver Lake across from Neutra’s famous VDL house, which was built for a tiny amount of money (under 10,000) and is the humblest of beautiful modernist houses, built with simple materials, and, like much of his friend Schindler’s work, a model for people of modest means to be able to afford a home that would have plenty of air and light, as opposed to the claustrophobic spaces that were common in the old country…or in many places where the weather made big windows impossible and impractical. These seemingly compassionate concerns of the utopian architects and social engineers of the 30s never “worked”, just like the neglected windows and dysfunctional showerheads of your childhood. So my question becomes, how does utopianism inform the downfall of utopias?

@Rita…

I think all these social experiments, from Unite d’ habitation, to Brasilia, to Belmopan, and a dozen others all suffered from the forgetting of memory, as it were. They were built at once and had everything except history. leCorbusier’s unite in marseille is now occupied by upper middle class professionals, and quite well liked. But the point is that social engineering always runs into this problem of people coming to live in a place they have no history with. Of course there have been experiments to tear down and build anew with the same inhabitants, but this always confronted the problems of any urban or even suburban center, and that was the wider issues of unemployment and class segregation and racism etc. It feels as if these wider issues subsumed the utopian dream which was always narrowly proscribed, and hence doomed. Of course place such as Belmopan were riddled with corruption, and just bad planning and design. The Neutra narrative is interesting, because in a sense he was a bit of sui generis. But the brutalist, what is termed brutalist, isnt inherently authoritarian……..in fact I rather like a lot of it. Same as I think LeCorbusier was misunderstood, at least now. Mark Wigley has written good stuff on this. —The problem was the actual social authority. In the US of course, planned communities suffered from the cultural myopia of the society at large. And the early onset of policing and this fear of the masses. I think few of them were very idealistic or utopian. Looking at them now, it feels like social manipulation. The right wing, the capitalist class will argue, oh, see, these silly dreams arent practical. The reality has nothing to do with practicality. It has to do with how this punitive mind set in the US felt the need to always extract max profit while making sure privileged communities stayed separated.

Yes the utopias are reactive but perhaps not so a-historical, in the sense of reacting AGAINST history, in the sense of wiping clean the slate, forcibly opening up to new ideas or drawing on new mixtures of ideas grounded in [someone’s reading of] history–and it must be said that history is a moving target not existentially fixed…Koolhaas had an interesting show (New Museum in Soho) a couple of years back critiquing historical preservation because of its institutional and philistine values (but mostly because he was lobbying to clear the way for new projects for, um, big firms like his.) The forcible opening can either be counter to dominant power or in league with it–or sometimes a blend…hence countercultural utopias like Hog Farm or the weird science/theater project of the Biosphere of the 80s-90s

Well……..but wiping the slate clean is wiping the slate of history, or memory. In terms of community, Im not sure thats reacting against history, so much as just ignoring history. Yes, one can introduce new social organization, and an effort to improve certain things…and as i say, Unite in Marseille is very nice, its very human. But in a sense, you have to have a relationship to the people of the area…and if the idea is to import an ad hoc sort of community….it needs social support, and thats what never happens. If you look at north african souks, or medinas, you see no signs, no streets or alleys marked…….its this chaos to the outsider. But it functions beautifully. Kowloon..,.,when china finally tore down kowloon, the people there didnt want to leave. And part of that was because life under the triads, without police surveillance or intrusion, was much better for almost all of them. These are sort of fascinating facts to plot into all this.

As for Koolhaas,….he just curated this thing at the Venice bienelle…..i think thats where it was……….that was just astoundingly trivial.

Alright, rita, I’ll take a stab at this one… I spent a while forming my “stab” and in the intervening time there have been some additional thoughts that I don’t directly address, but here it goes anyway…

How might utopianism inform the downfall of utopias…? Well, because we become slaves to a vision that the utopian ideal suggests… we become robots… we try to create a utopian state (whether this is a physical state, or a state of mind), and we attempt to control or to shape instead of trying to really see what is unfolding all around us. I think the dangers of utopianism are linked to the dangers of making a “dream come true.” It could possibly be the difference between learning to listen, rather than striving to tell. I think I may be able to use a quote from this particular post to illustrate this idea:

“But this is a necessary illusion in a sense, as Adorno points out, that society produces the contents of our minds, while at the same time ensuring we are blind to the fact of mediation. The post industrial hyper branded landscape is always in the process of covering up, and often covers up by pretending to lay bare”

There is always the possibility and problem of our own blindness to the very violence we perpetuate by fulfilling ideals without really questioning what these ideals entail, or where they come from, or what they might imply. It seems to me that all sorts of institutions have been set up to mediate our experience of reality, to distance us from the humanness of the other by carefully structuring our interactions. Sometimes this works out “okay,” but when ‘shit hits the fan’—or as I like to say, ‘when reality hits you in the face,’ you could be faced with the possibility of utter loneliness, or the overwhelming need to repress and deny an honest reaction to the experience.

I’m still not sure what a state of utopia might be like… it seems like the cliche visions (the community-minded, spiritual hunter-gatherer; the hot sun sparkling over cold drinks and bare bodies of fit, smiling people on some turquoise sea; a disneyesque castle in the clouds, with faeries in leotards feeding crumpets to a populace of “equal” citizens with no illness, birth defects, history of trauma… I mean, what would we do all day? Perhaps the new Utopia is a complete loss of consciousness, or an inability to converse with the physical world through our bodies).

I think that “perfection” is an inherently fascist sort of notion. If I were to describe an actual state of utopia that Might not be fascist, I think it sort of has something to do with what Steppling refers to as the “process of covering up… by pretending to lay bare.” This “necessary illusion” is the tension that we are perpetually trying to reconcile. Perhaps “utopia,” would be an energy, a curiosity, a consciousness that is willing to risk Uncovering that which has been covered up—to risk knowing too much—to risk un-knowing everything—to risk confronting existential uncertainties… There’s a certain “aliveness” in a struggle to become aware, to see possibilities in things beyond what they appear to be (a sort of defamiliarization, if you will). But I suspect that, as soon as we think we have found the “answer” or the “truth,” or even The Definitive “problem” (i.e. sliding glass windows, people who are homeless), we hit a sort of deadness, and that is where utopia starts to crumble… It also seems to crumble if we don’t bother asking questions and are indifferent to our ignorance—I suppose that would be the loss of curiosity, and agency.

I don’t know, sometimes I feel like I can DO utopia better than I can explain it… and it isn’t exactly painless… it is sort of like remembering and forgetting at the same time… never mind… fuck it.

I was thinking about this the other day, and asked my friend what she thought about it, and she concurred, that when people lose the ability to process suffering, they lose the ability to see beauty.

@calla & rita:

there is an interesting idea that was born out of LeCorbusier’s obsession with white…which is complex, and then revised by his followers in a sense. But this was that the “new” architecture was stripping away the 19th century to reveal a new Spartan and sleek shiny body underneath. The fact that white had to be applied was ignored in the pictoral aspects of the narrative. And this is what is so interesting…because it links to a variety of things, the volkish fascism of national socialism (reflected in certain ways in Heidegger) and the futurists, and is linked, as is everything in the 20th century, with psychoanlysis. And fears of contagion, and so there is almost a doubling of the early feudal communities of greece and north africa and spain where whitewash was a community project, for hygiene. But everything is also something else. And its important to try to tweeze apart the fashions and corporate manufactured image from their historical roots etc. So uptopia falls into this too. As Cala says, there is something puritanical about almost all utopian projects. Thats the dialectic. I had this debate the other day about women taking their husbands names when they marry. Both names are patriarchal….so its perhaps wiser to search out the dialectics of this, and perhaps in some ways TAKING the new name is more radical. In other ways, its not. In a third ways, its not either. … its all about finding the narrative and figuring out who wrote it.