Ivan Kliun

“The meaning of this parable is not easy to define. But one thing is clear: this type of parable is not to be thought outside the theatre, or rather outside a certain kind of theatre. In narrative prose Edgar could, of course, lead the blind Gloucester to the cliffs of Dover, let him jump down from a stone and make him believe that he was jumping from the top of a cliff. But he might just as well lead him a day’s journey away from the castle and make him jump from a stone or any heap of sand. In film and prose there is only the choice between a real stone lying in the sand and an equally real jump from the top of a chalk cliff into the sea. One cannot transpose Gloucester’s suicide attempt to the screen, unless one were to film a stage performance. But in the naturalistic, even stylized theatre, with a precipice painted or projected onto a screen, Shakespeare’s parable would be completely obliterated.”

Jan Kott

“King Lear or Endgame, Shakespeare Our Contemporary”

“At he unknown beginnings of the world, gigantic monsters embody chaos and emergence, in Babylonian myth as well as in the fabulous classical zoo that Hesiod set down; he traces our anthropomorphic forebears—the Titans and Cyclopes and Olympians—back to terrifying gorgons and dragons and sphinxes. John Boardman has argued in his book The Archaeology of Nostalgia (2002) that the Greeks were attempting to make sense of dinosaur bones they found in the landscape, and he convincingly compares the bone-white sea monster on a vase, lurking in a cave and ready to pounce on Hesione, with the fossil skull of a Samotherium, or Miocene giraffe, such as was found around Troy.

But rational conjectures of this kind, however entertaining, don’t explain the whole activity of the monstrous imagination, which revels in excess and assemblage; tricephalous and multilimbed, with arthropod and reptilian features such as ruffs, tusks, fangs, tentacles, and jaws, many of these primordial monsters are hybrids defying nature. They belong to dark places, those underworlds under land and sea—volcanoes, ocean abysses—because they embody our lack of understanding, and mirror it in their savagery and disorderly, heterogeneous asymmetries of shape. For this reason, at the same time that Olaus Magnus was making his marine map, artists conjured extremes of physical monstrosity to convey spellbound states, in which perverse desires are spoken and thrilling moral transgressions follow.”

Marina Warner, New York Review of Books

Reviewing Chet Van Duzer’s Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps

“There shall no stranger eat [of] the holy thing: a sojourner of the priest, or an hired servant, shall not eat [of] the holy thing.”

Leviticus 22:10

“Then Satan answered the Lord, and said , Doth Job fear God for nought? Hast not thou made an hedge about him, and about his house, and about all that he hath on every side?”

Book of Job 1:9-10

Ive often used the example of sixteenth and seventeenth century maps and the monsters at the edge of the known world as a metaphor for the off-stage. In times of expansion, but more, of psychic eruptions and disovery, of awakening, there are evident also anxities and dread. The changes in Attic Greece that helped form classical Greek tragedy, or the late fifteen hundreds in Elizabethan England, where a number of profound writers appeared and worked in a revived sense of the tragic. This also links to my last post about space, and architecture and theatre.

On these maps were images and ideas born within a world that had to deal in intimate ways with the danger and power of the sea. And of land. Storms were not satellite predicted. A high percentage who went to sea, never returned. A north wind or a following sea; these things were dealt with in intimate ways. Smells and sounds carried weight. Knowledge was traditional.

The Kott quote is seminal. Kott’s two major works, Shakespeare Out Contemporary and Eating the Gods, changed perception and practice for modern theatre. Kott gave Shakespeare an added political compenent. The Stasi were Shakepearean. As was the CIA. Kott most influenced, I think the perception of the History plays.

Jan Kott

The sea evokes the deepest of fears, and anxieties. One feels helpless in the face of the scale and power of the sea. I’ve always sensed that the horizon, more apparent in deserts and on the sea, connects us to one path, one allegorical journey, and forests and grottos another. The Grimm Brother’s sensed acutely the aesthetics of the deep forest. I remember in Poland, in deep forest (a country by the way, with very underrated and wild national parks) that quality of space and air that occurs where sunlight never reaches the ground. So dense and tall are the trees, that light sifts down, bouncing off needles and leaves and at the bottom is the fecund moss covered undergrowth. Reproducing through spores, growing slowly. It is the slowness that defines the meanings associated with deep forest. In deserts the horizon is clear. The dry air keeps things preserved. Things seem at a standstill. Plant life is defensive, and also quite slow. Things happen in the limited shade, quietly, privately. The desert is eternal. It is linked to death, to embalment. Things do not suffer mold, or infestation, but are baked and preserved. The forest is quiet too, but a different quiet; it whispers, and its moist. And decay occurs. The moist and the dry. The horizon and the grotto. Rock or moss.

Helmut Federle

All narrative is given birth out of primary landscapes. There are urban grottos, urban deserts, and our sense of enclosure is always linked to the anxiety and ecstasy of these spaces, the narrative is oriented in relation to the horizon. And from this space there is the figure in the landscape. The human. The stranger. This is really the bedrock stone floor of all narrative. It is also the origin or foundation of the scapegoat. In Leviticus the goat is slaughtered, blood spilled, while a second goat is sent out into the desert, to “bear the guilt away to some desolate place”. This is the scapegoat. So we have pure and impure, known and unknown, friend or family and stranger.

The Dionysian genealogy of tragedy obviously intersects here, and links to these primal anxieites. Human sacrifice became animal sacrifice, but this meant some sublimating. But the essential anxiety remained.

“Time after time one witnesses the role of scapegoats reverting to human figures known variously as Canaanites, Gentiles, Jews, heretics, witches, infidels and after the discovery of the new continents by colonial empires, unregenerate savages.”

Richard Kearny

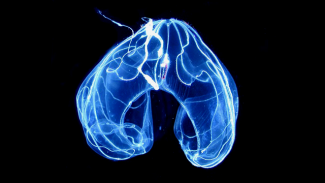

Bathocyroe, in deep water (NOAA photo)

Danielle Delnero

One could analyse color here, too. For yellow was the symbol for Jews. Yet it was also associated with sunlight. Yellow is the one color that both represents illness, God, and light. The contradictions are many. But my point here is that a basic anxiety fueled much of the symbolic response, and imagery. In the Garden of Eden, the tempter was the serpent. Now reptiles, cold blooded and seemingly unfeeling, were also worshipped for exactly those same characteristics. The serpent crawled on his belly, and his submissive posture links to sodomite imagery. There was a collective response to the anxiety of uncertain space, to a fear of non-being. The fear was of that which could not be defined. The Inquisition became sexual frenzy and all scapegoating tribunals since have expressed this terror of what can’t be seen or defined. In darkness things happen that we don’t know about. And what we do know about we feel guilty for. The stranger then, remains the architype of anxiety. Burning witches meant the mythic register of life had become confused with daily material existence. The anxiety was too great. Now, the presistence of monsters in narrative speaks on one level to the return of the repressed. One cannot feel holy without the scapegoat. The cycles of purging though have become condensed. Acts of symbolic purification dont hold for long today. A new monster appears immedietly. Today’s mass culture has essentially found a need for a non-stop supply of evil. It would be worth considering the eruption of school shootings, suicides, and workplace slaughter as an articulation of a new fusion between primordial anxiety and a society predicated upon domination and control. As actual engagement with the natural world becomes increasingly mediated, the surplus of bureaucratic malaise grows larger. The empty rituals of daily life are now little more than obligatory chores. The sense of sacred space more controlled and the society of punishment hovers above all of it. Today’s U.S. prison population expresses the excess of scapegoating and its failure. There seems today a narrative cul de sac in which purgation cannot operate.

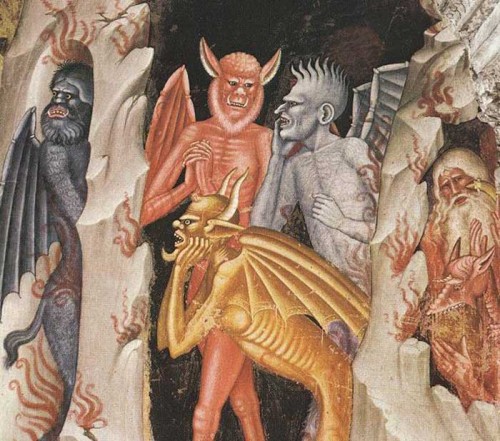

Fra Fillippo Lippi

Richard Kearny points out that in Beowulf, the hall is a refuge from mauraders. From the dangers of the *other* that savage the countryside. The enclosed space of safety. Grendal roams the border lands, and is described as a fiend from Hell.

Helen Bennett on Beowulf and the hall:

“Adding to the semiotic ambiguity of the hall in Beowulf is the use of hall words to describe structures other than large man-made communal buildings. Both the mere in which Beowulf pursues Grendel’s mother and the barrow of the dragon are called “halls,” simultaneously invoking contrast to and commensurability with Heorot through the qualification of the type of hall (e.g., niðsele, “hostile hall” and eorðsele, “earth hall, cave,” respectively). These qualifications stress the contrasting antagonist roles of Grendel (anti-thane) and the dragon (anti-king), while still conceding to them a common structure of habitation. But Grendel’s mere, termed a niðsele (1513) and a hrofsele (“roofed hall,” 1513, 1515), is all the things that Heorot is not: dark, watery, below ground, surrounded by monsters, and not “constructed.”

The creation of “border realms” is intriguing here, too. I’ve said before that for the U.S. today, Mexico looms as this necessary south, or land of darkness. It is the border to the white world of privilege. South America is beyond the border realm, a land of eternal darkness. The Puritan memory, the slave trader memory, the Indian killer memory. The fortress U.S., an enclosed hall of protection and cleanliness. American white myths always create a morally clean house at the heart of their world. And this obsessive need for monsters means the obsessive need for enclosing them. Prison America is a material expression of colonial anxiety about ‘catching something’ from the natives. Those overflowing prisons mean no amount of scapegoating is going to work. It is not working. No matter how many seasons Hannibal surivives (or how many versions of Dracula are produced, etc etc), no matter how many serial killers are created, the mechanisms now fail. And one might see the proliferation of franchises in mass media, copies of copies, as another version of this failure. The culture cannot recycle its repressed materal fast enough any more. Narratives are not really narratives now; they are reflexive spasms or fragments that recycle code, particles of meaning. Popular culture just brands everything; history is a brand. DaVinci’s Demons, Salem, Copper, etc. Shows that create the signifiers for history, the style codes, but leave out the history.

Andrea Bonaiuto

One of the recurring themes in pop cultural narrative today is the enemy within. Someone pretending to be just like *you* but who is really an enemy agent or an alien or a carrier of plague. This feels a lot like the paranoia of the ruling elite being played out in the kitsch narratives of Hollywood TV and film. Like the dragon in Beowulf, who comes from below, but not from outside, these stories of various trojan horses seem to fit seemlessly into this anxiety about exactly who one’s neighbor ‘really’ is. The stranger is the fulcrum upon which all narrative operates. But the stranger gradually became the scapegoat as well. Perhaps it always was, really. But today so precarious is the perception of the social order that the political radical is demonized outright. All dissent is terror. Some of this feels linked to the fragile nature of the collective identity of the ownership class. Those white men who make the decisions in boardrooms most certainly feel the invasion of minorities and women. Impotence anxiety is triggered. Health phobias. Civil rights and feminism are both akin to the Dragon from below. And increasingly there is a problem of external identity. How can we tell who is a secret agent? Skin color is one thing, but even that feels fractured and after all there is black President now. Its no surprise that the police crackdown on black youth has intensified for the fear of losing control is now being projected more intently onto the most visibly *other*. In pop culture today, suspicion is valorized, it is the hallmark of responsible adulthood. This suspicion is naturally really an interrogation of onself, too. Characters in almost all corporate drama today are suspicious and surly. The white privileged class who manufacture popular product feels uncertain of their own identity. And increasingly the narrative includes masochistic elements. Perhaps *I* am an enemy agent and don’t know it. Julia Kristeva is right when she suggests that many now project their own feelings of difference onto the *other*. The outsider, the alien. What we see in ourselves as not conforming is projected outward. The other HAVE to be different. The strangers to ourselves idea is part of what Freud described in his essay The Uncanny. Part of the experience of the uncanny is a recognition of familiarity in the strange and unusual. The mandate for familiarity in the culture industry is predicated upon the need to assure the ruling elite that nothing uncanny is out there. And if it appears, it can be quickly and effectively eliminated. Culture industry narrative does not want friendly strangers. It wants the threat.

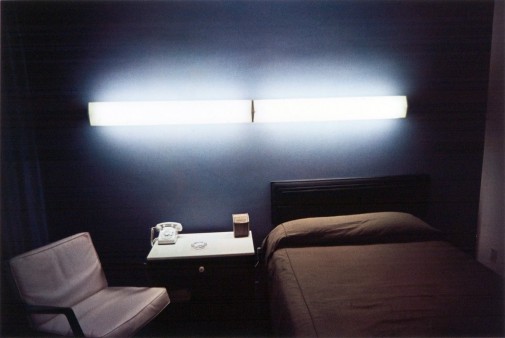

William Eggleston

I want to return here, though, to theatre, and the nature of stage space. For all this anxiety is both cause and effect of amnesia. And of the willfull blindness today of a population conditioned to accept the mediation and control of daily life and even of perception. The compulsive repetition of kitsch one dimensional plots is not done in a way that forms the memory that is an architype, but rather is done the better to not wake up. In Kott’s analysis of Macbeth, he writes: “A production of Macbeth not evoking a picture of the world flooded with blood, would inevitably be false.” Almost the entire play takes place at night. The nightmare is that sunrise never comes. I used that image in fact in a play but I dont recall anyone recognizing the allusion. But the night in Macbeth is a sleepless night. The nightmare occurs while awake. This is a very modern play, in fact. The world in which we live today is one in which the Spectacle insists on *now*. The *dead now* I wrote about before. The usable consumer populace is placed within a giant corporate run Casino and forced to stay awake. Kott says of Macbeth: “All the faces have the same grimace, expressing the same kind of fear.” The modern society of domination can be seen in the precursor landscape of Macbeth. Mud and phantoms. Nature is again a space of shadows, great empty halls, and primal anxiety.

Macbeth

Into the air, and what seem’d corporal melted

As breath into the wind.

There are witches in Macbeth as there are ghosts in Hamlet. In these tragedies the enclosures fail. Castles cannot be protected, horses break out of stables, and falcons circle the dead. The purging of guilt occurs when, as Kott says, there is awareness. Without awareness, there is only compulsive repetition. There is the failed scapegoating mechanism.

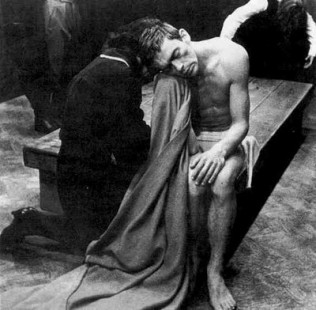

Jerzy Grotowski production, Constant Prince (Calderon), 1966

Freud pointed out that repetition is the worst kind of forgetting (per Kearny). The culture industry forgets in the worst way. For, as Kearny says, it has forgotten its own forgetting. But there is another kind of repetition, that of myth. The mythic ritualized alter of memory in which a community or collective memory is evoked. Under advanced Capital, as a system of exploitation, memory is annilhilated. The community has been destroyed in the name of the ‘individual’. Amnesia is fetishized. Forgetting is branded. And when this happens, nature is only a manufactured nature, and space is erased, and narrative becomes the repeating of lies. Today’s television and film product largely narrate the values of the ruling class. But such narratives betray additional meanings not intended.

The ghosts in Hamlet or witches in Macbeth are vehicles of memory. The monsters at the edge of early maps are expressions of anxiety. The monsters in Hollywood film are the *other*, the fear the establishment feels from what they see as a surplus population. Those zombie hordes are both repressed material and the demonized masses. But these symbols take on characteristics common to all monsters; they rarely sleep, they never die, and they finally cannot be kept out because, really, like the Dragon, they arrive from within the enclosure. Perhaps this is connected to the sense of nightmare in which no enclosure can hold.

It is important to remember that cutting across all of this is our embedded bias in bourgeois thought processes. Jameson called them “superstructures of psychological or lived experience and the infrastructures of juridical relations and production process.” These are the textual points of reference for bourgeois identity, and they infect our language at every level. And they reproduce, or help reproduce our interpretation of the world. Part of what I hope to point toward in this post (and others) are ways out of the suffocating banality of the stories we tell ourselves as a society.

“The process of adjustment has now become deliberate and therefore total…The individual’s self preservation pressupposes his adjustment to the requirements for the preservation of the system.”

Horkheimer

He added: “Adjustment in our times involves an element of resentment and surpressed fury.”

Horkheimer saw the pragmatic intelligence that came out of the Enlightenment as force destroying an ability to experience nature. What he called its qualitates occultae. Instrumental reason has erased narratives that contemplate nature with awe and wonder. The diabolical aspect of this (and Marcuse wrote him about this after reading Eclipse of Reason) was that under a society of domination the remnants of objective reason would be criminalized and eventually return to a purely irrational and destructive ethos. Bataille, Freud, and Benjamin all saw the first World War as a product of the negative force of the instinctual. And for them fascism was only going to continue under the dynamic in play. The deforming of the instinctual under a society based on control was inevitable and no return to an undialectical version of an imagined past was advocated. The thrust of Horkheimer’s thought in the 1940s, was similar to Adorno’s, that culture must be dialectical, and must negate the negation of the status quo. The rise of a cultic worship of the individual has led to the prevailing belief today (in the U.S. anyway) that poverty and inequality are the result of individual shortcomings. That a failure of personal values, or personal responsibility is to blame. And from this one can see the blindness and abridged ability to contemplate the physical world. Narratives give no meaning to nature, only to man. Descriptions of the concrete material world are embraced so long as no deeper meaning is given to what is described. A footnote to this is that Horkheimer believed the truest picture of the world would be found in the vision of criminals and those labled insane.

The violent conservatism of today’s ruling class includes vehement racism and intolerance for difference, and a hatred of the poor.

James Turrell

I wanted to add a sort of footnote here. The empire of faux left and faux intellect is alive at Mother Jones, Jacobin, In These Times et al. Mother Jones just published this http://www.motherjones.com/media/2014/05/24-live-another-day-jack-bauer-politics-torture-muslims-liberal-tv-show

This is rather stunning, except I’ve come to expect it from places where Bhaskar Sunkara has a hand. To be clear, 24 is the realm of white supremicism, Imperialism, and sadism. It is violence porn. It is also, additonally, PURE fantasy. It is propaganda but this new version, which I took it upon myself to watch includes demonizing of Serbs and Russians, the heroin dealer is an Arab, and every single character is an asshole. How is it a culture embraces a show with only unpleasant and ill mannered people? Somewhere the idea of professionalism is now equated with just being offensive. This is white male violence being valorized, of course. It is the wet dream of the American white male. But as an odd final coda, Suebsaeng once worked for the Bangkok Post. Oddly, so did I, but only for a week or two. This is, like Jacobin and In These Times, an actually reactionary corporate press masquerading as progressive… a word that has probably never had meaning but most certainly now has none. In a week of Donald Sterling, it is worth remembering who pays for what one sees and reads. With net neutrality soon gone, this blog may be as well. I’ve never advertised anything on it, and I won’t. But stuff like this review of 24 will continue to be the norm and further train the western populace in racism and torture as valid practices and beliefs. History is a brand; shows like Salem or DaVinci’s Demons, bear exactly no relation to the past, but a character named Cotton Mather appears, and that’s all OK, because amnesia is fun, and fidelity to some version of historical truth is so five minutes ago. Of course expecting anything else is naive, and the very idea of anachronism is itself anachronistic.

https://www.commondreams.org/further/2014/05/05-2

The above link is not a story told by Hollywood, the stuff Suebsaeng validates, it is a story that will remain occluded because there is no white center to it.

NBA owner Donald Sterling was a known bigot for twenty years. David Stern helped Sterling when he, Stern, ran the league. He helped the likes of Clay Bennet, too, Reagan admirer and fracking king, and Brian Roberts who is CEO of Comcast (speaking of net neutrality) who owns the 76ers. And the league is now slapping itself on the back for taking out a dottering cancer riddled old bigot, mostly because he is a vulgar one and Clay Bennet a more presentable one. Herb Simon owner of the Pacers is a real estate speculator and strip mall builder (with brother Mel) and another rabid Republican, Micky Aronson, Israeli gangster…er…businessman and yacht lover, and Peter Guber, Hollywood schlockmeister, former partner of the grotesque Mr Streisand.. er…Jon Peters (full disclosure, I had the misfortune to have worked on a film project of Peters, a man of bottomless ignorance and crudity). Rich white men own sports franchises, and none of them are not just as bad as Sterling. If one really needs an example of how corporate ownership of both the public mind and its funding, there is this: http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2014/02/06/stad-f06.html

Yutaka Takanashi

This is why I admire the great tragedies of the Greek and Elizabethan eras. There are no “Others” who are monsters/scapegoats. In Oedipus, the king atones for his own sins. He imagines the sin must lie elsewhere, and that fatal ignorance — the inability to consider that the taint might actually be within himself — becomes his downfall.

In King Lear, the king has to reach the depth of human degradation before he can actually understand what it means to be human. It is a wonderfully ambiguous depiction of the outcasts. The significance of the King and Edgar (as “Mad Tom”) in the storm is that being an outcast does not make you alien to human experience — in fact, you are more human than the civilised villains who shut you out.

I like the way you talk about the Greeks. This idea of trying to make form of the unknown makes sense. There be dragons.

I have a strong suspicion of Greek tragedy and yet I can’t stop studying it. Within the scapegoating frame, tragedy seems like the form of the 1% – a wonderful instrument for communicating the values of the state (restoration of the status quo), of purging people of undesirable urges (catharsis) and valorizing empire.

These are fascinating comments. I’m not sure I agree with either, but Im not sure I dont fully disagree either. Talking about greek tragedy is very complex, and its hard to discuss it in short form. The truth is, we are guessing at what really went on, what the collective experience was based on, and what these festivals looked like. Benjamin remains maybe the most valuable critic, and his German Tragic Drama book is pretty useful. Now Shakespeare is complex in another way. And I think what Exir says is both true and not true. This is why The Tempest is my favorite play. But maybe i need to do a whole posting on tragedy soon.