Fra Angelico, Last Judgement, detail.

Today’s audience for mass culture deserves some observations. At least a brief historical perspective. It is most interesting, perhaps, to start with a few thoughts about the bourgeois, the evolution of this class, at least as it effects culture and narrative. If the remote beginnings are traced to the 11th century, the more conventional idea of the bourgeois class dates to probably the 17th. But already by Victorian times, there was, as Moretti points out, a sense of compromise. Already there is a sense of fatigue with the institutions of power, and already the bourgeois resist the use of the designation.

In the United States, without a traditional nobility, the economic reality still demanded a middle. And Americans have always embraced the idea of a “middle class”. And middle class seemed to promise a class mobility denied those under the heritage of peasant, proleteriat, and nobility. Nobody ever wanted (in the U.S) to be described as working class. Still, as Sarah Maza points out, ” …the existence of social groups while rooted in the material world, is shaped by language, and more specifically by narrative; in order for a group to claim a role as an actor in society and polity, it must have a story or stories about itself.”

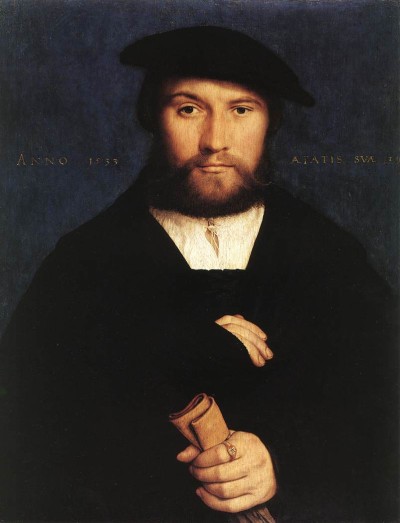

This is perhaps only half true, but it is still relevant. And for Dutch merchant bougeoise the portrait was the story they wanted told. The privilege of paralysis in a sense. The under class had to move, and use its hands, and make noise. Portraits are silent. The hero of antiquity; the warrior and knight were gradually being replaced by business. This was not uniform, but in general the class divides were in locked in a tension of perception. The reality of repression became a topic of narrative (as Moretti, again, points out, in Mann’s novel Buddenbrooks). The language of economic domination then becomes ever more stolid and tedious. There is a resentment of the vigour and energy in the prose of the marginal classes that began in the late 18th century I think. The final outcome of this economic language is the boring and inpenetrable political language of today. The legal and political prose of the ruling state.

Pieter de Hooch

The prose of the 19th century novel was already laying out a grammar and style that would later prove to be so useful to the culture industry of the post modern stage of advanced Capitalism. Adjectives, not nouns. The description of feeling, and the subjective sense that often reality was created by the author. The American middle class solidified its self image after WW2, with a quick acceptance of consumer culture. The commodity was the new expression of bourgeois identity. Now, this is, of course, over simplified but one can see in many 20th century U.S. poets a reaction to what was being heard as mushy language, and from William Carlos Williams to Hart Crane, to Cummings and Pound, the search was for the concrete. The critical edge of writers early in the century cast a long shadow.

“the viper stirs in the dust, the blue serpent glides from the rock pool

and they take lights now down to the water…”

Canto XC

Hans Holbein the younger

There was intuited an approaching century of messy and tortured syntax, of marketed ad copy and a de-linking of sensual experience from words. There was something in those poets that longed for the cold earth, even if damp and chilling. There was a distrust of comfort. The new middle class of the 1950s American dream was to be all about comfort. The various branches of poetry; many heavily influenced by Pound, but on up to the Beats, as well as figures such as Charles Olson, and Louis Zukovsky were ascetic, at least in language. For all the drugged excess, personally, of many beats, much of the writing was disciplined, contrary to popular mythologizing.

“By the road to the contagious hospital

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast—a cold wind…”

William Carlos Williams

Spring and All

There was certainly a shift that occured after WW2, that is attributable in some part to the escalation in advertising, and then the advent of marketing science. Looking back at this idea of the U.S. middle class, the post war climate was relentless in espousing a pseudo-clinical sense of health, an anti bacterial almost hospital like cleanliness, that was coupled to the new consumer addictions. The era of branded cleaning supplies (Tide detergent was developed in the forties, and was the first ‘heavy duty’ laundry soap, and released in 1946 it became within a year the largest selling detergent in the world, and so popular that for a while stores in the U.S. limited it to two boxes per customer) and work saving technology for the housewife (which is rather large topic and worth a post all by itself). Interestingly, the fifties saw an extraordinary spike in toothpaste and toothbrush sales, and a public interest in oral hygiene. What this oral fixation suggests is unclear, but I can remember that teaching of how to brush occured even in schools, and the idea of mouthwash use everyday (as an aside, Listerine was originally invented as a surgical antiseptic, floor cleaner and for use against gonorrhea).

The sense of the middle class was already hugely anti-intellectual, and while the pursuit of technical matters was seen as logical, and a future source of income, the study of arts and humanities was suspect. How the middle class saw themselves, as an ideal, is less clear to me. Moretti points out the similarity to Victorian bourgeois, and I suppose that is correct, but the American middle class of the fifties was also all about activity. Productive leisure, hobbies, and sports. The rise of spectator sport is probably something in need of a definitive study. Baseball had already been established as “the national pastime’, but after WW2 the National Football League and National Basketball Association were both suddenly of great interest (though hoops lagged behind a bit, only taking off when the black inner city embraced it). Idle hands are the Devil’s Workshop. Americans had boys take wood-shop, or as I had to take, metal shop. Girls took home economics…and there is a good piece here on the loss of home economics in public schools.

http://www.alternet.org/how-fast-food-industry-destroyed-home-ec-hook-americans-processed-crap?paging=off¤t_page=1#bookmark

There is an interesting note at the end of this piece on the basic mystification of daily life by corporate marketing, and by extension education. From the dropping of finance to auto repair to cooking, schools stopped teaching anything practical, nor do they now teach anything demanding of serious focus, and god forbid they actually teach critical thinking. They teach science, but under the aegis of corporate or military research. What they do seem to teach most is how to self brand. Creative writing and any cultural appreciation is mostly about the writer and not what he or she writes. It is about how the subject ‘feels’ about the artwork, not the artwork and its meaning to society, or its role historically. Pop psychology and the culture of therapy masks the training of good consumer expertise and the reiteration of obedience. But I digress a bit here.

Pat Steir

From the 50s on there was a split in the U.S. middle class. The marketers were selling fashion. And fashion became a dream of the upwardly mobile. As Moretti says, the second side, ‘comfort’ was more related to the lower end of the middle class. But cutting across this were two other factors. One was the raging militarism and anti communism of the state, and the second was the rise of youth culture and the narrative created by youth culture. The “sixties” being the fulfillment of this.

There is a book Im going to have to read soon on the history of stimulents (by Wolfgang Schivelbucsh) that discusses the morphing of tobacco and coffee from luxury substances to medicinal to pleasure items for the masses. But on the one hand, the early stages of state prohibitions on intoxicants (not of course alcohol) and narcotics was a morally driven attack on pleasure, but the marketing of minor stimulents escaped due to the fact that they aided the worker in working longer hours. Like beetle nut for Rickshaw pullers, the rise of tobacco and coffee served to prolong the work day. Heroin made people stare at the top of their shoes for 8 hours. One was banned– the anti work ethic drug (it had formally been legal and sold in elixors for women, as was cocaine) and the other marketed. One could become a connoisseur of wine or brandy or even beer eventually. The ‘sixties’ however cut across a good portion of this narrative. And for the middle class the hostility directed at hippies and anti war protesters was really about their refusal to sign on to the narrative. The beats and rock and roll rewrote part of the script. Not all of it, of course, and the easy assimilation of sixties radicals into the status quo is proof enough of this.

At lunchtime under Black oak

Out in the hot corral,

—The old mare nosing lunchpails,

Grasshoppers crackling in the weeds—

“I’m sixty-eight” he said,

“I first bucked hay when I was seventeen.

I thought, that day I started,

I sure would hate to do this all my life.

And dammit, that’s just what

I’ve gone and done.”

Gary Snyder

Hay for Horses

If one looks at the nature of this rewriting, the disruptions of the final real avant garde movements (though the late 70s up to the mid 80s provide a coda in a sense) was expressed in a disdain for both the tedious prose of the Dental Clinic and law office, and the complexities of the 19th century novel. Again, from Lukacs to Moretti and Frye the analysis of the 19th century novel has been extensive. Sentences of multiple clauses, of gerunds that move along to meet past tense, to then conclude with infinitive. The pulp fiction of Thompson and Cain stuck to one clause sentences born of newspaper reportage. The effect however, of both Beats and pulp novelists has probably not been good for future MFA writers. Or at least some of the Beats. There was also born the literature of urban paranoia, and the literature of de-mythologizing America. And one sees elements of this in everyone from Burroughs to James Baldwin to Pynchon. The rise of institutional teaching of the arts also served to extinguish the radical voice, or rather to bury it out of sight. By the 70s the sound of American fiction had already started to feel neutered. As Flannery O’Connor said, when asked if she thought MFA writing programs discouraged young writers, “not enough” she answered. Now one can always find exceptions, but it is interesting to see in American film the watershed occuring in the late 70s with the rise of blockbuster culture in corporate studio strategies. Institutional storytelling. And so the launching of narrative intended for children but sold to adults.

But back to this idea of comfort. The bourgeois portrait, and the sense of realism in Dutch landscape painters, implicated the viewer in a certain narrative even if the painting itself had stopped narrative for a moment, frozen it. In France the middle to late 1700s saw a shift in the narrative that also included the viewer, but in a completely other way. Michael Fried’s remarkable book Absorbtion and Theatricality, Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot points to (among many other congent and stunningly perceptive observations) that the work of Chardin and Greuze set in place figures lost in thought or absorbed in some focused activity. They were not paying attention to the viewer. The work in the Netherlands of Vermeer and De Hooch almost one hundred years earlier, were raising questions related to this. The bourgeois lost in thought, in a world of acceptable comfort. In a world of frozen narrative. For the right to freeze narrative is purchased by hard work and the cunning of the rising merchant class. The portraits of the Dutch painters are never fun.

But back to this idea of comfort. The bourgeois portrait, and the sense of realism in Dutch landscape painters, implicated the viewer in a certain narrative even if the painting itself had stopped narrative for a moment, frozen it. In France the middle to late 1700s saw a shift in the narrative that also included the viewer, but in a completely other way. Michael Fried’s remarkable book Absorbtion and Theatricality, Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot points to (among many other congent and stunningly perceptive observations) that the work of Chardin and Greuze set in place figures lost in thought or absorbed in some focused activity. They were not paying attention to the viewer. The work in the Netherlands of Vermeer and De Hooch almost one hundred years earlier, were raising questions related to this. The bourgeois lost in thought, in a world of acceptable comfort. In a world of frozen narrative. For the right to freeze narrative is purchased by hard work and the cunning of the rising merchant class. The portraits of the Dutch painters are never fun.

Now it is true also, at least to a degree, that the Dutch golden age of painting was achieving this stoppage by instinctively turning to still lifes and landscapes of distance. But this probably exceeds what I am trying to get at here. The world of Vermeer is the world of middle class comfort. At a time when comfort and fashion rather overlapped. It was also the foreshadowing of what marketing sold in post war America. A clean scrubbed kitchen floor, children in clean clothes, adults groomed and neat and with tranquil expressions. Now, the capitalist sensibility sits like a lacquor atop all these representations of reality. Or narratives of reality, really. There is always a narrative. The French painters after Chardin, or into the 18th century in England with both Gainsborough and Reynolds were hired to paint property. The former, Gainsborough, being the outlier in a sense. For Gainsborough was one of the original modernists. I may be slightly alone in this opinion, but for Gainsborough, the narrative included him. Was the viewer considered? Of course. But the viewer was partly an insider. Reynolds was the formalist. In a sense the problem with Reyonlds was that time froze but seemed likely not to start up again. In all these variations came questions of the viewer and of what story the patron was asking the painter to tell. John Berger, who I think did see Gainsbourough as ahead of his time, said, of the painting of Mr and Mrs Andrews; “…(they) are not a couple in nature as Rousseau imagined nature. They are landowners and their proprietary attitude towards what surrounds them is visible in their stance and expressions.”

By the late 1800s, there was an urban underclass, and the mirgration of rural populations.

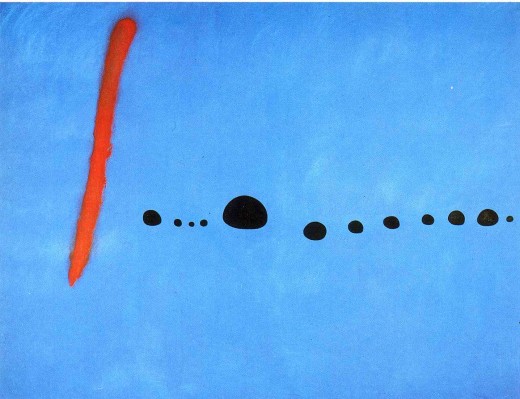

Thomas Gainsborough

British industrialization was imitated by other European powers, and it travelled to the U.S. as well. The classic age of Imperialism, and its effects on narrative are maybe beyond the scope of this short posting. What I am trying to suggest however is that a lot of factors had multiplied in the hundred years between 1810 and 1910. The first world war was probably even more significant for western narrative than the second. The second was only a hideous logical coda to the first. But in both painting and narrative the reaction to this complexity was multi-faceted. The avant garde in both narrative and painting, and in theatre as well, was partly a reaction to the shocks of industrial scale death. The notion of home, or place, and of identity in this ‘middle class’ (if speaking of the U.S.) were intensified. ‘Going home’ became a trope for all narrative in a way shorn of its earlier mystical ornamentation. Home meant those scrubbed floors and comely family, and leisure time. It also meant, however, after WW2, the need to be seen as an effective consumer. The avant garde by the fifties, in painting and sculpture had come to ignore the viewer. It was also the final chapter, generally speaking, of sincerity. How the rise of irony fits in with all this is worth thinking about. One response to the work of Tony Smith and David Smith, and Serra and to Abstract Expressionists was to privilege surface, at the expense of depth. The fallout from this, which in itself is perhaps valid, though I’m far from sure about that, was to valorize surface. And soon, artworks as commodities, as ‘things’ that one didn’t have to explore in any way. The audience was the same audience as the shopper at the supermarket. The action painters, the color field after them, and in general all the abstract painters of the post war era were oblivious to the viewer. The abstraction was a defiant act, and it was frustration as mystical gesture, as a Sufi like dance frozen in time (again).

If the capitalist sensibility values the instrumental, and a fixed universe and set parameters for story, then comparison becomes crucial. Like shopping, like the manufacture of “choice”.

The emphasis over the last thirty years on originality, and innovation, is only a smokescreen. The reality is that nothing original is actually allowed into the cultural landscape at all. The best work in theatre, since mid 20th century, have been radical extensions of previous models (Pinter, Kane) while a regressive movement toward the most stable kinds of bourgeois narrative is validated by the establishment critics and the commercial and academic experts. The idea of entertainment is, of course, linked closely to the idea of “fun”. And fun has very little meaning beyond its negative implications — those things which are ‘not’ fun.

That culture favors the idea of entertainment (fun), and it results in a strange alienating effect, for nobody quite has a handle on what fun actually means.

Are we having fun yet?

Model train town

Fun is not really either quantifiable nor is it qualitative. How much fun did you have? Fun is just a catch all designation without any real meaning. Its not wholly different than when people say “lets party”. There is a general sort of notion of what that is, but it is meant to be vague. It is a filler, a place marker for experience. Or for non experience. Fun is inherently anti intellectual. It is another way to say ‘not work’. But it is active ‘non work’. It is part of this middle class emphasis on movement and activity. Hobbies are something now derided as being un-hip. Stamp collecting or building model airplanes. In a sense such things are too productive. They result in a material thing. Now you have a balsa wood airplane. Now what do you do with it? There is no destination to hobbies. But they still demand productivity in some fashion. “Fun” requires nothing but a kind of passive ersatz participation. Terms like “popcorn movie” are only another way of saying fun movie. Which in turn is another way of saying disposible. Forgettable. The narrative that haunts the viewer or reader cannot be disruptive. Melodrama, especially sentimental melodrama, is OK, because the emotions are false. They are borrowed. The seriousness demanded by the tragic is disruptive. It is also an interrogation of emotion, and it posits the collective in some way that is decidedly discouraged by Madison Avenue. Serious artwork demands a focused attention, and it costs the viewer something. Presumably that cost is worth the experience.

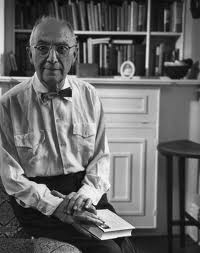

William Carlos Williams

The hard boiled crime fiction of the 40s and 50s, in the hands of Jim Thompson, David Goodis, and the rest of the Black Mask writers, as well as in the classic detective stories and novels of Chandler and Hammett, served as ‘low brow tragedy’. Thompson is not fun. Chandler is, in reality, amusing, but not fun. The spectre of the rotten soul of society is too present. This work was hyper masculinist, and often misogynist, but it was moral, it introduced questions of society, and more importantly the prose was shorn of the natural rhythm of the 19th century novel; this was the prose of newspaper reporters. Hemingway made use of it, and later Carver (at least after Lish got hold of the manuscripts). This prose quickly however took on mannerist pretensions, and added almost effortlessly a sort of ‘loss of affect’ style. Theatre and film began to resemble a style introduced, really, by the Chiat Day ad agency. And as an aside, its quite possible that the most underrated influence in narrative presentation came by way of Swedish director Roy Anderrson’s commercials, which were much copied by Chiat Day.

Joan Miro

Across all of this, though, has been the bourgeois identity. That identity posits a reality. Visually it is perspective. In narrative it is the cadance and sentence structure of industry and observation. All this has been written about quite a lot, and yet the disintegration of these forms and structures over the last thirty years has been almost willfully denied, if not ignored. The 19th century novel still was a version of the oral story teller. It retained the feeling of night fires, the acceptance of submission to the author, the understanding that this might take a bit of time. But time was there, after work, the time of reflection, and it was a time of not working. The idea that a knowledge was being imparted. Secrets exchanged, and applied to one’s own life, and filtered through one’s own problems. The idea that corporate sponsored TV series, or cable series are doing anything like the same thing is the real problem in criticism now. Nobody seems to want to acknowledge that The Sopranos or Mad Men are not essentially improvised week to week, in an effort to quickly snare Neilson ratings, lest they be cancelled. Corporate money drives the entire thing, in total. Absolutely. Period. In the UK and Denmark, and France even, the pressures are quite different and while creating hits remains the mandate, the sensibility remains qualitatively different. It may still be melodrama, largely, but often it rises above that level. In the U.S. you have a far less sophisticated audience, and you have a far deeper corporate state in media. Shows are not greenlighted because of some inherent quality, they are greenlighted because the sponsors and network trust the hack showrunner or creator or because market research says they need a medical drama at ten p.m. as the lead in to the song contest show at eleven. The storyteller, the oral narrative, and even theatre, required time. The giving of attention over a period of time. Reading Tolstoy requires time. Today, I suspect it would be described as ‘requiring an investment in time’, suggesting a payoff at the end. But today, time is used up. Nobody ever stops working. But it is also a question of the the nature and quality of attention given. Today, as electronic media increases the fragmentary quality of almost everything, I feel few people give complete attention to anything. People have been industrious, at least under Capitalism, but as traders and merchants, for hundreds of years. But they allowed periods of relaxation, and reflection. I am not sure people relax today. And when they do, there is a quality of the compulsory about it. Partly it is the pressure to act the part written for you by society. That part is less questioned today than ever before.

There is now, as labor is deterritorialized, and as global communications never retire for the night, where night and day are only glyphs, or keystrokes, the sense of industry and enterprise and hard work brings with it an anxiety about relaxation. There is always a new text message, always a new email, always an employer trying to send you an SMS or trying to phone or FAX you. For the poor, the anxiety is acute, and frequently reaches despair and panic. There is additionally, the sense of being watched. Mass governmental surveillance is now an open fact. But people have sensed it for a long while. Someone is watching me. The sixties paranoia is now proven to be legitimate fear. The war on youth, especially poor and working class youth, means teaching them anything is pointless.

“Well, water goes down the Montana gullies.

“I’ll just go around this rock and think

About it later.” That’s what you said.

When death came, you said, “I’ll go there.”

Robert Bly

When William Stafford Died

Moretti makes a point about the embedding of the social contract in the voices of many 19th century novels. He says “Are they the narrator’s words, spoken through Emma’s lips? No; they come from the sentimental novels Emma read as a girl, and never forgotten…they are commonplaces, collective myths: signs of the social that is inside her.” He suggests the composite discourse of the bourgeois doxa. The accumulative sensibility of bourgeos society. In a sense this was, Moretti says, the point of Bouvard and Pecuchet. For the society of the West today, there is no way to tell where the ironic joke ends. If Flaubert made those two men debate how to tell a stupid novel from a novel about stupidity, today there is no way to know what is ironic and what is sincere.

James Storm

The recuperation of form is found in unexpected places, and without the creator’s awareness, usually. Stephen King is not recuperating the Gothic novel, or rarely anyway. However, there seems to be an increasing number of kitsch TV series in which paternal ghost figures haunt the narrative (Dexter, The Tomorrow People) or ghosts of other loved ones (Sleepy Hollow, and The Walking Dead). In a sense these devices are just expedient in a creative culture where imagination has largely dried up. In another sense, there is something sort of in these shows that feels drawn to forms that remain, frustratingly opaque. Or it is possible that Hamlet is the ultimate template for post modern corporate narrative. Whatever the analysis, and I’m just sort of skimming the surface for now, looking to find clues to how the a middle class or bourgeois class has had to face its own demise, or recognize its own fictions. Its own history, even if by accident, as it often seems. And to ponder the nature of what is seeping in to the fill the void.

Paragon Park, Nantasket Beach in Hull, Massachusetts.

Anthony Van Dyke

As a final sort of addendum to all this, I think that one of the lingering problems with a lot of people, both on the left and the right is that somehow there remains a deep distrust of the metaphysical in art, and this then extends to abstraction (and to other things, of course). And I was reminded of this when the discussion of Freud’s more speculative and anthropoligical and philosophical writings came up recently, but also just a sense that many will recoil from any, absolutely any, universalizing theories about culture. And mostly this is a sound policy, but not completely. This came up listening to Vilayanur Ramachandran, who is a neuroscientist, and writes a bit about culture as well. He tells what is now a well known story about the seagull mothers feeding their chicks. The chicks peck, instinctively at the mother’s beak (which happens to have a red dot on it in some species). And experiments were done replacing the beak with a disembodied beak, and finally with a white stick that had a red dot. The chicks always got excited and expected food. But when the researcher painted the stick with three larger red stripes, replacing the dot, the chicks got hyper excited. The beak was special, and fetishized. It was a super beak! There are a host of other pretty fascinating ideas lurking just in the field of neuroscience and visual processing. And in autism. Since this topic came up in the comments last time. For this is about focus. And the autistic savant who can draw exceptionally detailed images, for example. This savant-like ability has to do with removing the non essential, though while highly “practical” in some sense, it suggests that in visual aesthetics there is a pursuit of something, some form of recognition, that links to primordial operations in our brain. In the metaphoric reptile brain (call it what you like). And perhaps it is a form of primal practicality. That the imposition of domination, masquarading as practicality, has poisoned that word and idea. I wonder though if the increase in austism (if that is actually, in real terms, true) in the society, and if the general cultural mimicking of autistic symptoms, isn’t some strange adaptation to over stimulation, to saturation of image and sound. Burroughs used to think so, in a sense, when he spoke of ‘word virus’. The idea of of a society bombarded with information, hyperbranding, sales copy, manipulated message, ubiquitious print ads, meaningless and pointless noise pollution, hasn’t started in some fashion to devise self protective mental mechanisms. It also makes a certain sense as a response to the destruction of community, of acute isolation, the cultural and social envelope of electronic media replacing human socializing. The constant repetition of solipsistic stories and essays. One can watch couples absorbed in their texting while eating dinner, often even at movies, or out walking. The draw is toward this electronic reward. If once the problem solving of visual processing produced an instinctive reward of recognition (deciphering camouflage for example, or foreground\background puzzles, etc) in man’s early evolution, and which isn’t now used for any concrete purpose, has been replaced by the hyper stimulation of screen reward, coupled to the anticipation and consequent anxiety of electronic ‘results’. I suspect the urban landscape of CCTV plays a role in all this, as well. I tend to avoid these anthropoligical models because they elide a lot of social and political factors, and become used as excuses for more repression and social domination.

But back to aeshtetic acts of discrimination. The primordial brain I suspect does have structure, and that structure, or those structures, are replecated in all visual processing. The other problem with these models, though, is the exclusion of narrative from the discussion. Everything, all image, is part of a narrative. And even abstract artworks require mimetic engagement. And it is exactly on the point of intersection that I think important things are to be learned. As for consciousness, or the mysterious layers of the reptile brain, whatever you choose to call it, I do tend to think at least on one level the role of awakening to mimesis is related to or attached to those reptile traces of instinct that still remain. And I know few writers or artists of any sort who don’t instinctively believe this. And it is why I have found that creative people (and god knows I hate such descriptions because it’s been part of marketed new age self branding these days) have trouble getting along, often, with non creative people. There are certain types, insurance salesman, military lifers, and politicians, prison guards, etc, who have stunted that aspect of their brain. They live in the real reptile world all the time. These are very often those suffering under that emotional plague Reich describes. And that plague is what Capitalism spreads. Control breeds emotional disfigurement. Surveillance is a form of violence. The entire society, save for the 1% at that top, are suffering degrees of intentional emotional deprevation. The system kills the creative, it kills that part of the primordial brain.

Ad Reinhardt

There was a series this year put out by BBC2, created by Steven Knight, in six episodes, Peaky Blinders. Knight wrote the screenplay for Dirty Pretty Things, one of the more supportable films about immigrant life in the UK. He also wrote the script for Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises. A good script, if a less good film in the end. I only mention this because of the exceptionally good acting, which remains something the British do as well as anyone, and because one has to say, it is very well shot. Not just well shot in the sense that production values are high (they are, but not as high as most US hour dramas) but because of a basic intelligence at work. The anachronistic music (including the Nick Cave theme which was also used on an old Aussie show, ‘Jack Irish“) somehow is evocative and not troublesome. Perhaps because this is not a realistic show. This is post WW1 Birmingham as a semi-Biblical landscape, an old Testement dream of societal horror. The flames of furnaces dot the background of almost half the exterior set ups, and the endless coal black streets and Patricidal fantasies of the shell shocked men returned from the fighting in France all give a slightly purgatorial texture to the narrative. And then there is Sam Neil. If for no other reason, it is worth watching this show for Neil. His Northern Irish cop, replete with an exagerrated accent straight from nightmares, his repressed homosexual rage, his puritanism, and his sermons to roomfulls of cops are just indellible. The penultimate episode features an IRA man, played by Tom Vaughan-Lawlor, who’s appearance achieves something like a small film within a film. Cillian Murphy and Vaughan Lawlor mostly sit and talk, pushing money and weapons across the polished table tops. It is a strange disturbing drama of repressed rage and impotence, of feverish patriotism and the delusions that accompany such obsession. And it ends as it must in an irrational violence. If one wanted to point to good genre television, this would be it.

Sam Neil, Peaky Blinders

Thanks for the recommendation, I’ll go check the series out. Always love BBC stuff, and Sam Neill is a particular favorite actor of mine. Hugely underrated — probably because he doesn’t go for all the emotional pyrotechnics that Academy Awards love.