“Cretto 1”, Alberto Burri

“…the certain realization that Kafka’s entire work constitutes a code of gestures which surely had no definite symbolic meaning…”

Walter Benjamin, On The 10th Anniversary of Kafka’s Death

I want to continue on fromn that last post, and also to incorporate some of the long comments thread, and also try to more specifically look at this idea of violence in the West, and its cultural expressions. The link below is almost a daily occurance now.

http://www.commondreams.org/further/2013/09/12-1

The new theatre of violence is this temporary stage on the side of the highway.

This mini drama encapsulates the thrust of the white male system of domination. The beating of a woman, who’s crime was (in theory) driving while intoxicated (though she seemns to have passed the sobriety test). Against this bit of psychosis, is the bigger psychosis …a ratcheting up for war in Syria. Which of course has actually been the creation of a conditions under which it is suitable to ratchet up for war. The projection of U.S. power globally is the raison d’etre of the militarist state. The U.S. has always been a war culture. It is founded on extermination. Six hundred tribes, millions of people killed. And killed with chemical weapons (small pox blankets, etc) among other things.

This was the week of the anniversary of 9-11. Now, I often wonder that anyone believes 19 mostly Saudi nationals, coke snorting lap dance buying ‘religious fanatics’ somehow highjacked planes and etc. But you see, the narrative is a movie narrative. That a film was in fact made specifically about the phantom flight 93, that self vaporized over Pennsylvania, is not surprising. The public will believe that which is most like a movie. “Lets roll!”. At the same time, the public loves to have the fairy tale version of U.S. power presented repeatedly. So, against this Florida cop beat down of a small pretty and non threatening woman, the world the US public wants to believe in, seems to exhibit two characteristics simultaneously. One is U.S. military perfection, starring a white (preferably) male star, who will be steroidal and cute, and a narrative in which everymen come to realize the importance of the cog like role in the great patriotic project of US supremacy. Stallone and Tom Hanks.

This (Hanks) is the Aaron Sorkin version. The affluent everyman.

The buff action star is sort of the Bourne Pretzel or whatever type of franchise. *White House Down*, which sort of story works in harmony with *fear from without* version, which includes zombie films and virus films. What you cannot have is reflection. What you cannot have is maturity, the maturity to listen to the echos of the narrative as it happens.

And lest you think somehow that the political class is not simply an extension of the new filmic reality, there is this:

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/2013/09/nsa-director-modelled-war-room-after-star-treks-enterprise.html

Here is a quote from the article: “”When he was running the Army’s Intelligence and Security Command, Alexander brought many of his future allies down to Fort Belvoir for a tour of his base of operations, a facility known as the Information Dominance Center. It had been designed by a Hollywood set designer to mimic the bridge of the starship Enterprise from Star Trek, complete with chrome panels, computer stations, a huge TV monitor on the forward wall, and doors that made a ‘whoosh’ sound when they slid open and closed. Lawmakers and other important officials took turns sitting in a leather ‘captain’s chair’ in the center of the room and watched as Alexander, a lover of science-fiction movies, showed off his data tools on the big screen.”

He had doors made to go “whoosh”……seriously? Well, as the culture is strip mined by corporate media and telecoms, and as the under class and poor around the world have their stories stolen, their culture appropriated and usually then destroyed, it makes sense that the creative vacuum of the ruling class would turn to bad sci fi movies. I’ve actually not ever trusted science fiction buffs, its a particular sub phylum of fandom that seems to harbor a very fascist sensibility. That said, there is even more to be seen in this small news footnote. It is the authority of movies, the sense of authenticity is greater in film, then in real life. This is, again, the failed sociological, and bureaucratic, risk averse managerial mnind set. The specific inherent qualities of direct experience are pawned for the ones that resemble movies.

There is also the need to aestheticize violence. In shows such as Sons of Anarchy (more on that below) violence is very quickly recovered from, as it is in almost 99% of Hollywood film and TV.

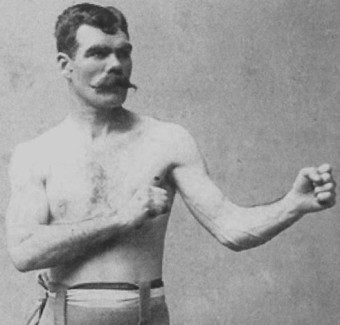

Christina West, after police beating

Nobody suffers lasting scars, dizziness, concussions, nerve damage, even missing teeth, from violence. Either you are shot at, amid close up blood splatter, or at a safe enough distance the death is signified by a fall. This was the style code of the 50s western. *Indians* falling off their horses as ricocheting bullets were fired non stop. Codes for death. Western culture has created little space for the ‘idea’ of death. And in a sense, there is very little idea of violence. Humans are fragile. If you look at boxing, the history of boxing, the invention of the padded glove changed everything. The impetus was for increased safety but what it did, really, was allow for more punches to the head (and more ring death). In fact, prior to the use of gloves, there mostly were no head punches. Why? Because the head is hard bone and will break your hand if you strike it. Now, in Hollywood…if you see prize fights from the late 19th century, you see bare knuckled fighters hitting each other repeatedly in the head. You cant do that. Those old fights went 70 rounds because they were much closer to wrestling, with a lot of body punches. In fact, one the things that not infrequently occured was liver and kidney damage from prolonged blows to that area. This damage often changed the complexion of those fighters. Their skin darkened, often turning a blueish hue.

Sullivan was actually, apparently, in his youth a rather remarkable physical specimen, a bit like Jack Johnson, and Dempsey many years later. I think the point here is that the violence of bare knuckle fighting was directly linked to a sense of codes and honor and male potency. As the regulartory bodies imposed rules, gloves, and as sport took on increasing economic importance, the sense of business eclipsed these codes. This digression was really to point up the damage of getting hit. Especially getting hit by someone who, as Mike Tyson used to say, had bad intentions. People can survive a good deal if prepared, but even the best prepared can crumple in a heap if a baby finger gets broken. Violence is always contextualized. And perhaps the most horrific acts of violence are actually the most premeditated. I think this is why capital punishment is felt in the deep and blackened corners of our psyches. It is dispassionate and rational.

Enzo Traverso’s excellent book, which I’ve mentioned before, Origins of Nazi Violence, suggests WW1 as the watershed for state violence, for it marked the start of anonymous industrialized death. It was organized and planned. And it was on a massive scale. The experience of WW1 on the entire population of Europe cannot be overemphasized, I don’t think. For the experience of this violence, the perception of it as well, retained a certain directness. It was unmediated to a large degree. The physical cost of the War was rexperienced with the return home of soldiers, many with horrible disfiguring scars. Even by the time of the second world war, there were some mediating mechanisms in place. And WW2 also marked an escalation in technological warfare, culminating in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

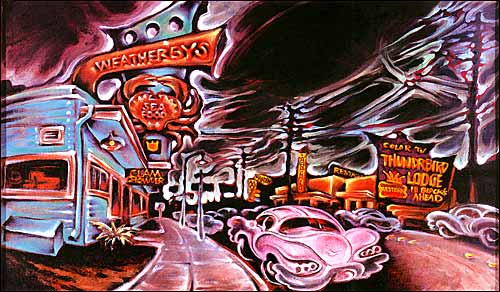

Martin Wong

World War 1 though, signaled another shift. The enemy became invisible. And invisibility meant the enemy was dehumanized. As Jean Norton Cur wrote, warfare became an organized slaughter carried out with an “absence of hatred”.

Traverso wrote ” Warfare against these ungraspable enemies introduced an anthropological break, reveling a new perception of human life that essentially paved the way for the genocides of the future”.

The industrial level death machine now merged the soldier with the factory worker. It was Fordist warfare. And it was the start (intensified with WW2) of a normalizing of mass death. The experience of hand to hand battle, the heroism of the individual soldier, the warrior, was transfered to the manager and planner, the designer of the machinery of slaughter.

Engles said that so long as the proletariat uses the state, it does so to hold down its adversaries.

“It is clear there is no freedom and no democracy where there is suppression and where there is violence”.

Lenin

The de-personalizing of death and killing that began in WW1, and grew in WW2 has now reached an apex with introduction of drone assasination and bombing. If in WW1 the enemy was unseen, he was still close. Those soldiers treated for trauma after the first world war would speak of the closeness of the enemy, but a closeness shrouded in mystery. They were fighting ghosts, and spectral figures, often in gas masks. The drone “pilot” is not close to his target. The enemy is far away, and only a blip on a screen. No ghost haunts the air conditioned control room in Nevada or Utah or Guam. The violence has no double now, no stage on which a tragic drama can be played out. There is less and less sense of individual heroism or sacrifice, there is only extermination, bullying and a sense of unreality. The enemy is unseen , you the joy stike operator is unseen. The bodies of those targeted (or the hundreds hit by, sort of, accident) are seen, but only seen dead. And not seen in the West. Most military personel, of course, do things other than direct drone strikes. Still, the KFC, and McDonalds, the milk shakes and bowling allys, create an atmosphere of a vacation share/rental, not a foward operating base. If soldiers and factor workers merged over the course of WW1, todays solider is merging with a sort of high school athlete, given amphetamines and roids from his coach and encouraged to go out and give it up for the Gipper.

Except there is no set of formalist constructions to walk into, psychologically, or morally. John L. Sullivan and Jem Smith aren’t there. A military that once ran on a vague pretense of moral codes, the playing fields of Eaton, and West Point or Annapolis, are now just clubby business schools for sons of Generals, or those with a weird psycho-sexual character formation.

Christina Cordova

There is a sense now, also, of the crushing of community awareness throughout the U.S. Lenin had said that the small commodity producer would linger around the edges of the worker’s communities, creating a petit bourgeois atmosphere, corrupting and distracting. Its an interesting remark seen one hundred years later, almost, the revolution having run its mostly dissapointing course. The sense of meaningless distractions, of commodity addictions, and of banality is a description of life in the Spectacle. Those young soldiers who navigate their joy sticks for better angles on groups of Yemani men, or Pakistani, including children, can take a break after launching a few hell fire missiles, have a Big Mac, an order of fries, and chat with some friends at the Px. The solemn and visceral rituals of mud and blood and lack of sleep that transfigured the WW1 trench soldier, provided the gravitas that death had heretofore naturally accepted as its right, are gone. The young killers are not haunted by the screams of the dying, they have no gray black lines beneath their eyes, eyes sunken deep into their gaunt faces.

But the ghost lives on somewhere. The ghost is, the doppleganger that looks back at you, a part of the organic mimetic process, must now find expression in camcorders mounted atop police cars. The greek chorus is the low resolution documentation of pointless almost arbitrary violence. Though, clearly, it is NOT arbitrary.

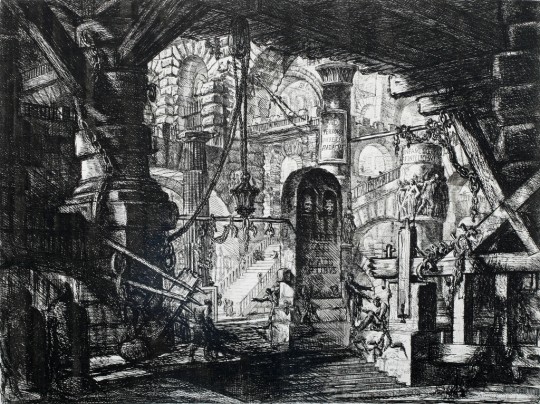

This distracted quality, a partial engagement with the world around one, is in a sense the post modern embrace of the trivial over the mysterious or enigmatic, of shock and pornography over the sacred, and of cleverness and irony over, perhaps, tragedy. In the last post, and the comments, there was much debate about Heidegger and his writings and analysis on the Pre Socratics. The issue though, for me, gets lost in arguing about Heidegger, because the issue is this failure to engage with culture. Marguerite Yourcenar in her essay on Piranesi, wrote that a century before Piranesi drew his tragic ruins and fantastic prisons, Poussin and Gelee had come to Rome, fascinated with its grandeur and with its deteriorating structures. But for them, it was all background for some personal reverie on nobility. It was all a bad stage set. For Piranesi: “…he has explored the remains in person, in part to unearth the antiquities he makes a business of, but above all to penetrate the secret of their foundations…”. The texts of the distant past, whether Greek or Tibetan, or Indian or Mayan, require some kind of trembling and fear. And if not, then the world is just a bunch of Safeway receipts and parking tickets. Perhaps it is spiritually good to sit a ponder a single word for a weeks.

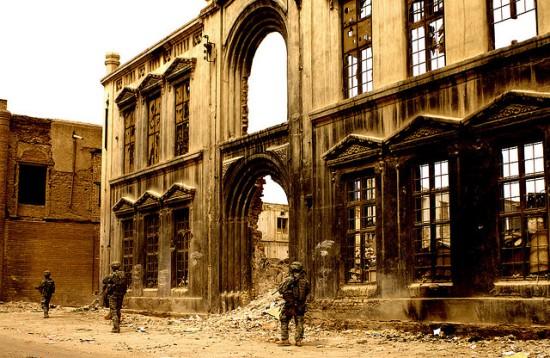

U.S. soldiers in Baghdad

Piranesi in the end created a far more imaginary allegorical landscape than Poussin ever dreamed of, and by his almost deranged obsession with the details of the material, with the ‘opaque identity’ of the stone and granite, and with duration rather than instability, he prophesied a coming world of control and punishment. It is in the opaque identity of the texts of Sophocles, rather than in the condescending European canonization. The history often asked for has of necessity to be a false history, at least until more of the enigmas of sacrifice are revealed and pronouncements of the oracle deciphered.

Piranesi matters for another reason, too. As Yourcenar insightfully points out, the Prisons are much like Goya’s “Black Paintings”, works of secret knowledge. These are also dreamscapes. The strange pessimistic dreams of one reconciled by a dark transcendence. The resolving of an impossible space with its echoing and doubling in a unconscious space that prefigures everyone from Kafka to Beckett, to Freud and Man Ray, Bacon and Kiefer. If the terror of drone violence feels more nihilistic even than shock and awe did a decade earlier, it is because space has been further erased. There is less oxygen. And sure, its not going to matter much to those on whom the bombs fall, but it is an indicator of cultural negation that horrifies by its sheer banality and stupidity. The culture of Obama era America is the commodity TV series which those 20% educated (mostly white) audience treats with greater affection and concern than they do their parents or children. The culture of Breaking Bad and Jenji Kohan, of Homeland and Game of Thrones.

These are the new Delphic prophecies. High end culture remains a well marketed side bar to all this. Dmytri Kleiner has an amusing (and correct) riff on Dave Eggers here…

“Here’s one self-described genius, Dave Eggers, describing the work of another, David Foster Wallace:

“[Infinite Jest] appeared in 1996, sui generis, very different than virtually anything before it. It defied categorization, and thwarted efforts to take it apart and explain it. […] This book is like a spaceship with no recognizable components, no rivets or bolts, no entry points, no way to take it apart. It is very shiny, and it has no discernible flaws. If you could somehow smash it into smaller pieces, there would certainly be no way to put it back together again. It simply is.”

It’s hard to image a more blatant or wretched example of mystification. As a description of Infinite Jest, Eggers’ words are simply meaningless. They’re better understood as a prescription, telling us the proper reaction to the book, which is slack-jawed incomprehension. We should contemplate Infinite Jest as our ape ancestors might have contemplated an alien monolith, or a Catholic peasant might have contemplated the Holy Trinity: an object of wonder beyond analysis or understanding.”

And this is right. Its the world of Rachel Kushner, of James Franco art critic, and of Marina Abramovic. Kleiner adds this ….

“artistic genius has stayed with us, getting more rancid by the day. Today, “genius” is mostly about disguising the process by which Great Art enters the canon — the privilege, the nods and winks and manoeuvres, the sheer luck. (Behind every great artist you’ll find stories almost as sordid as those behind every great fortune.) Today, as dissatisfaction with high culture rises and wonder declines, “genius” smacks of desperation: a cultural elite trying to prop up its sagging moral advantage by appealing to mystic forces.”

Paddy Slavin, late 1890s

And this is right, too. The problem is Kleiner inches rather too close to the cynical in all this. One can appreciate Mozart without buying into the Peter Shaffer version of kistch bio. And appreciation does not fall from the sky. It is not granted without some effort being expended. Which brings us back to the trajectory of violence over the last century. The erasure of allegory, of history over all, and the trivialization of the human. If Benjamin (as I wrote last time) could point out that after WW1, the value of life had seemed to decline slightly, today it has declined through additional forces, working out the increasing suffocation of creativity, the ridicule of compassion or altruism, and the absolute eroticizing of violence and murder.

Now again, it is far too easy to get all PTA about this, and sound like the Christian Family network wanting to censor rap records and bare breasts. Our own constant mimetic life dialectically stands up against the primal trauma of the splintered self.

Enrico Castellani

Every story is a crime story.

The problem arises when there is no story. There are only the indicators for where a story once was. As Big Julie puts it in Damyon Runyon’s Guys & Dolls, when he takes his own dice, which have no spots …but Julie says, “it’s ok, I had the spots removed for luck….but dont worry, for I remember where da spots formally was”.

We remember where the narrative formally was….sort of. Except not really. The new cynicism is that which feels most comfortable in snark and ridicule. And it’s about the easiest thing to do given how vapid the new Oracles of HBO and Showtime really are. One cannot seperate the addictions to comforting junk TV from the growing totalitarian state. Breaking Bad is a hit because (in addition to being well shot, mostly) it offers the salve of mild but correctable horror, to the real horror. The police arent so bad. The ATF in this show are not the same ones that torched and burned to death screaming children and women and adults during the Waco siege. An ATF so savage and emotionally dead that even while knowing babies were living inside, they manufactured a conflagration so intense that people were barbequed in tens of seconds. Dying, shreiking in agony.

No, not on Breaking Bad. In this show the villains are really drug users in the end, and Mexican drug cartels. The underclass. Not the nice white families that agonize over a lot of white people issues. Oh sure, the white high school chemistry teacher goes rogue…but only for his family. So, there are crime stories and there are crime stories.

Hans Kohn wrote, in 1939, “The racial theory, as evolved by the National Socialists, amounts to a new naturalistic religion, for which the German people are the corpus mysticum, and the army the preisthood.”

Today, cable television is the new Church, celebrities a sort of rotating preisthood, but the religion is militarist realism. If the Nazi’s created a naturalistic sort of volkish cultural spin on what was already a sort of 19th century bourgeois demand, today the realism is corporate military realism. It is the manufactured surveillance state reality TV show. When Truman Show came out, the horror embedded in the idea didn’t resonate. This season it’s Speilberg’s (by way of Stephen King) Under the Dome (which title pretty much explains the show in total). How I came to love my big glass prison where I’m watched 24-7. The screen of the CCTV feed is in a sense the new mystery, the goat entrails of the 21st century. Only, the diviner is a minimum wage high school drop out who dreams of promotion to the local sheriffs dept.

Kent Bellows

Adorno said you could hear the traces of the cafe fiddler, still, in Shoenberg, and Yourcenar says, even in Piranesi’s most formal Prison images, the faint echo of an aeolian harp drifts up from the ruins just out of sight. But without community, or rather with only your new Samsung Galaxy to provide community, the modern day citizen either embraces the Truman Show the feel good 1984, or they join in watching the Academy Awards or Super Bowl, and treat bombing raids or “humanitarian interventions” as special episodes of their favorite military franchise. Anyone who really thinks the audience watching Obama speak is not hearing a TV show has simply not been paying attention.

Into this new sanitized narrative framework comes the spike of increasing violence, both in severity and in frequency. There is no horror, really, seeing what was done to Christina Harris. The violence of drone impersonality, of the masked world war one infantryman, and the high flying bombing raids of World War 2, to the napalm of Viet Nam, and the various cruise missile exercises since (from Pakistan to Somalia) all sort of arrive at the joystick in the Nevada desert, then it is also true that the destruction of dreams, and of the unconscious mimnetic and mostly the limited mimetic of any kind, is resulting in a frozen steroidal ideal, an identity shaped by video games and reality TV and a constant barrage of Pentagon advertising, where ever less educated, less socialized, and seemingly less intelligent white men are attacking the citizens they are paid to protect (and who historically they never have). If there is to be some form of engagement with and formation of, a new culture of opposition. An aesthetic resistance, it is going to probably contain within itself any number of contradictions. This was something Adorno was certainly aware of. Zuidervaart wrote….”To be reconciled, culture must reflect on its own tendency to repress nature, particularly that which is internal to the human subject”. Self reflection then, must be able live within some sort of originary mimetic dialogue. The greatest danger for a cultural existence is simple obliteration. The Fukushima, shock and awe drone death we may all face soon enough. The second danger is in the educated classes split between white male liberal fellowship with militarism, and the equally destructive white leftist snark of those convinced either that bad art is good art is the message is right, or that art is too dangerous, too unpredictable, and hence tacitly to be ignored.

Piranesi

The formalism Adorno saw in Hellenic classicissm, and neo classicissm, was, as Zuidervaart points out, for him the epitome of mythic beauty. Now, there was an aesthetic violence at work, just as there was in Dionysus and Apollo on the Tragic stage. The dismissal of art’s history simply furthers the barbarity of the current fascist state. The non-identical, the tensions of the failed reconciliation is the real force of aesthetic resistance. The resurgent racism of today’s shrunken theatre of violence is a recreation of the ‘first encounter’ of colonial journals, circa 1810. These slave narratives, the savage and the white god, are now in play in close to all cultural product out of Hollywood. The young who sense the bankruptcy of the society they were born into and now are feeling the boot heel of the system in more and more acute ways. The war on the poor is now particularly the war on the young. And even more particularly the war on the non-white poor. So, it is increasingly important culturally, to seek the alegorical, even if one finds strange bedfellows there. The instrumental logic of vulgar Marxism can be as dangerous as the provincial bromides of the liberal white class. The sensibility of the Tragic myth, as it appeared in Shakespeare, in Milton even, and up through Beckett and Growtowski and Kanter, is one in which the rational scientism that backgrounds all snark, left or right, is subsumed by something we recognize in those first texts of Greek thought. It is not even (though it is, clearly, also) just the recognition of a mimetic origin, that sacrifice had allegorical dimensions, and that finally, this was the raising of the value of the human, not the devaluing. In Dimytri Kleiner’s good and amusing piece, he also adds, again pretty correctly the fetishizing contours of European high culture:

“Genius”, like gymnastics, has its roots in early German nationalism. German nationalists wanted to resist all that French talk about reason and universal brotherhood, which they saw as cover for French imperial ambitions, and assert something mystical and folkish and distinctly German in its place. They wanted to install figures of national worship, figures that could define and unite a culture, figures that could precipitate a moral and spiritual awakening of the German people. They were holding out for an artistic hero. What Shakespeare supposedly did for the English, they hoped Goethe and Schiller could do for Germans.

These ideas helped to seed other, rival nationalist movements, and to this day, genius is closely related to nationalism. New nation states are always anxious to establish a pantheon of hero-poets who embody the mystical national spirit, and established nations are always on the lookout for another genius of the national culture. You can see this in the quest for the “Great American Novel” and the canonization of national laureates.

The stature of artistic genius further increased in the 19th century, in the Romantic era of European culture. Romanticism was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, and the Romantic genius a way of asserting the values and education of old money against an upstart industrial class. As high art became accessible to nouveau-riche industrialists, it became important to emphasise that its leading lights had an innate mystical quality no merely talented clogger could attain. Artists became full-fledged heroes in their own right, and to attain the status of artistic genius became the highest aspiration of any sufficiently cultured and sensitive young man. Then as now, “genius” was a category largely reserved for men. Women could at best aspire to be muses: inspirations for male genius.

Like a lot of bad ideas floating around today, artistic genius was not all bad in its original context. German nationalism, hard as it is to believe today, was once a positive political force: in the divided German states of the early 19th century, it united the common people against their feudal rulers. Even the Romantic movement had its good points, working to preserve the value of the emotional and natural against the rational and mechanical, and emphasising that the numinous and sublime still had their role in human experience.”

The Romantic movement had more than a few good points, in fact. And one of them was to see in early Hellenic thinking, and in tragic drama, the source material for mimetic enrichment. The spiritual if you like. From Holderin to Novalis and Lessing, the Romantics reclaimed the Dionysian energy of the Tragic dramatists, as well as the idea of an ideal aesthetic form, as well as developing the idea of a modern tragic. Schlegel said, Shakespeare wrote interesting tragedies, Sophocles wrote objective ones. The difference was, for Schlegel, modern man was concerned with his subjectivity, not with fate. But the point is that to form any aesthetic resistance means to digest that moment of shift, from oral to written, and from daemonic to rational and ordered. Within that mythos there is something of the potential for rupture with the growing police state, the new slave culture, and an intoxication with volume violence. The violence has no specific purpose individually, but it serves to make clear there are no limits on this. It normalizes fear, and it noramizes the behavior of those who are always scared.

Ashurbanipal Palace, Nineveh, 640 B.C.

The Italian Alberto Burri is among the few contemporary artists possessed of, at least partially, a tragic sensibility. Burri’s most emphatic and convincing work has been his land works, but his story goes back to pre WW2, in Umbria where Burri was born and raised. He came from a working class merchant family, not destitute, but hardly affluent. He became enamored of fascism and signed up to fight. He was assinged as a medic in Libya. The experience of death and suffering changed the young man. He surrendered at El Alahmein to the British. He spent the last year of the war in a camp in Texas, of all places. Burri was seen as uncooperative. He returned to Italy after this, and took up his passion for drawing. His second passion was to study Ancient Greek, both language and art. New York Times critic Souren Melikan wrote of Burri in 2012, at a retrospective:

“By 1949, it was as if Burri had never considered painting figural subjects. Small compositions in tempera on cardboard or paper would fall within the category of Abstract Expressionism if they were the work of a New Yorker in the 1950s. There is a Willem de Kooning fury about one of them, with erratic curves jotted across color splashes, but the scale is tiny in contrast to the New York artist’s large canvases.

Another small composition is a patchwork of irregular blue, red, black, rusty brown or even white panels reminiscent of the Paris school abstractionist Jean Bazaine.

In 1955, the restless Burri changed tack yet again. There is a violently Expressionistic mood about his abstract picture “Drips,” painted in oil on masonite. Rusty brown and black shapes interlock, making part of the picture look like a large jigsaw puzzle in which bird-like cut-outs can be discerned. Dark horizontal lines from which short strokes go up or down like dripping paint are set off by an orange background. The picture is vigorous — and sinister.

Total blackness triumphed a year later. The gleaming surface of “Black T” done on wood in tar, oil and pumice stone signals the beginning of the end of Burri’s strictly abstract phase. It is as if the painter sensed that this was a dead end. In one more abrupt about turn, the artist switched to different means to express destruction and deprivation. He picked up scraps of discarded sacking that he glued on wood panels painted a uniform black.”

Gebellini, Alberto Burri

Burri had rejected his youthful ideological beliefs, he had rejected all beliefs in a sense, and looked to the stone and cuniform writings of Mesopotamia, and even earlier Summarian tablets. Burri had seen the horror of war as a medic. His paintings were convincing in the way only those with certainty can be convincing. Burri is also a romantic. And it is from this romantic core that his most important work seems to spring. Burri created a huge cement land art in the abandoned town of Gebillina,Italy. An earthquake had leveled the town and the townsfolk moved eighteen kilometers away. Burri covered something like 130,000 square meters with cement, into which he created crevices and cracks. There is little point in describing this work. It has to be seen, and seen in the context of Burri’s entire career. It is really a sort of extension of the Cretta pieces, which are among my favorites. Burri had studied tropical diseases in medical school in Perugia. He didn’t discuss the war much, and the prison camp in Texas even less, except to say he became aware of Pollock while there. Burri’s vision is informed directly by the engimatic nature of ancient texts. And his work is infused with tragedy. But it is not melodramatic, nor is it self consciously dark. It is simply what can be said, with the materials chosen. The same as Piranesi, his countryman. Same as many of the post war Italian painters and sculptors. But Burri is also not a propagandist. The land works conjur up Pasolini’s same love of the Italian hills, and of Jean Marie Straub’s Moses and Aaron, in the timeless sense of figures in a wide landscape, austere, a sun light bleaching all things. It is the sun in Godard’s Contempt, and it a sun of warmth, though. It is warm, and it can be blinding, and it insists on distance, its privacy, its enigma, but it nourishes.

Unless the artist trembles before the solidity of the material, even if, and perhaps especially if, that material is text ….then the results are trivial.

Family, Detroit 1962, Elliot Erwitt, photog.

A final footnote on Sons of Anarchy. This is the story of two shows. Kurt Sutter’s show, and the show after Kem Nunn was brought on board. Now, Nunn is a favorite novelist of mine. One of those unrepentent genre writers who transcribes something truthful from a specific region, and culture. Nunn never tried to do more than tell the truth about a part of Southern California not usually seen. What Nunn brought to this show …and in startling fashion… was a certain feeling about the working class. About the raw edged crappy apartment buildings, welfare, and bikers, and more, the fatalism of the underclass in America today. It’s still basically a kistch sort of macho biker fantasy, and at times it veers into camp. It is also a pretty curious Biker club, and of course relatively sanitized. But if you listen carefully, the cafe fiddler here is Kem Nunn. There is a beating heart of darkness and a feverish sort of anti rational spin in the scripts now. And, perhaps most importantly, at times there is an honest picture of working class life in the US.

Alberto Burri, 1947

Speak Your Mind