” Mediation is no less to be inferred from the relation of art to nature, than from the inverse; art is not nature, a belief that idealism hoped to inculcate, but art does want to keep natures promise. It is capable of this only by breaking that promise by taking it back in to itself. Art is inspired by the negativity, specifically by the deficiency of natural beauty, in the sense that so long as nature is defined only through its antithesis to society, it is not yet what it appears to be. What nature strives for in vain, artworks fulfil; they open their eyes. Once it no longer serves as an object of action, appearing nature itself imparts expression, whether that of melancholy, peace, or something else. Art stands in for nature, through its abolition in effigy. All naturalistic art is only deceptively close to nature, because analogous to industry, it relegates nature to raw material.”

Adorno

I wanted to just talk a bit about painting in light of the endless discussions about film and TV. And I want to think a bit about what I said last time regarding the false optimistic. The false hope that destroys narrative in a sense, and derails the potential for awakening in art. But then I got to thinking about how art is taught. All art. From theatre writing and acting, to painting and filmmaking, to prose. Normally I’ve not included poetry. For I think (until recently) that poets were the most keenly aware of how form works, and of the non-identical. But, in fact, there are now such tsunami after tsunami of just dreadful poetry washing up on the psychic shores of the West, that one cant seperate them from the rest.

And I have no intention of doing a definitive survey or overview. But one of the things that is always problematic in film, or almost always, is that the studio work is mediated by economics, and all TV suffers the same tensions. There are some indi films, though usually they financed the film with corporate or studio money. Not always, but very often. In painting the broad issues have been in existence since the Abstract Expressionists, the acceleration of movements since WW2, and the destruction of the avant garde has all rendered the art world succeptible to many of the same issues of reproducing the false consciousness of American capital.

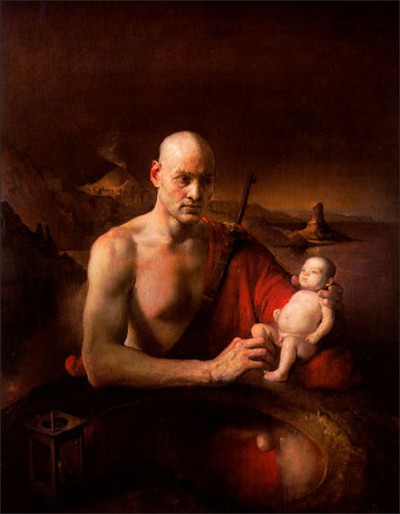

Odd Nerdrum

The Odd Nerdrum phenomenon is a good starting place in one sense.

One reviewer on Nerdrum:

“His repertory of New Old Master showmanship camps in full feather past the footlights. Nothing here supports its own publicity as a Rembrandtian critic of modernity. Mr. Nerdrum is a parodist. That his parodies are mistaken for prophecies is a testament to P. T. Barnum’s grasp of public credulity and appetite for spectacle. In the end, failed prophecy is a form of nostalgia. It is dispiriting to see technique lavished on an art running on empty” (Mullarky 2004).

Nerdrum is not uninteresting, however. His self promotion and persona aside, I think at the least one has to take his position seriously enough to analyse it. His manifesto “On Kitsch” (and he uses the word pretty differently than I do) has garnered a whole movement and quite a few imitators.

“Kitsch is passion’s form of expression at all levels and it is not the servant of truth. On the contrary, it keeps relative to religion and truth. A well-painted Madonna transcends its holiness, and Kitsch leaves truth to art. In Kitsch, skill is a decisive criterion of quality.”

Odd Nerbrum

So maybe it’s NOT that much different than how I use the word. There is no question that it is appealing to attack the art market, even if it is by valorizing some of the very tendencies that are used to create that art market. Define ‘skill’ is the obvious first question. Skill in this sense means duplicating the world we see around us uncritically. Skill is joined in the mind with realism. You duplicate the parts accurately, a bit like a camera. Of course for Nerdrum this means duplicating the world as Renaissance painters saw it. And really, that is sort of the problem that starts off almost all discussions of art. Nerdrum decries truth as belonging to art. Kitsch (Nerdrum’s kitsch) is not about truth. It is a sort of comforting idea borrowed from a self created ‘past’. And skill is a narcissitic valorizing of technical virtuosity that reflects more the training of the artist, and institutional conservatism than it does anything transcendent.

But the problem is really this, as Martin Hielscher puts it, in an essay on Adorno:

“The task of aesthetics is not to comprehend artworks as hermeneutical objects. In the contemprorary situation it is the incomprehensibility that needs to be comprehended. It needs interpretaion, calls for a philosophical response. This interpretation often speaks of suffering of the false life, of the how the administrative world people are constantly betrayed by what is sold to them as product, as entertainment, as language, as easily accessible cultural event or object. “

And allow me again to quote Adorno:

“Yet something frightening lurks in the sound of birds precisely because it is not a song, but obeys the spell in which it is enmeshed. The fight appears as well in the threat of migratory flocks which bespeak ancient divinations, forever presaging misfortune.”

There is a need, and Adorno was for his entire lifetime, working to analyse this, for culture and art to access an archaic stage of our being. That he was never satisfied with such a description, is beside the point here, but it was closely linked to this quest for understanding the non-identical in the artwork. The enclosing of life experience within the great industrial instrumental system of domination, of the racist un-freedom granted through the constant selling of entertainments and aesthecized propaganda, creates the obvious need for a rejection of the administrated world that is packaged on a nightly basis for TV consumption, and in film, and in painting and literature. The non identical is antithetical to commodity exchange. The artist is not expressing “some-thing”, but is involved in a mimetic dialectic in which the artwork is not describing something (i.e. instrumental positivism, the ruling ideology of scientism and capital) but is itself an expression of itself. It’s not a theme or a message or a subjective position. It is a form of thought.

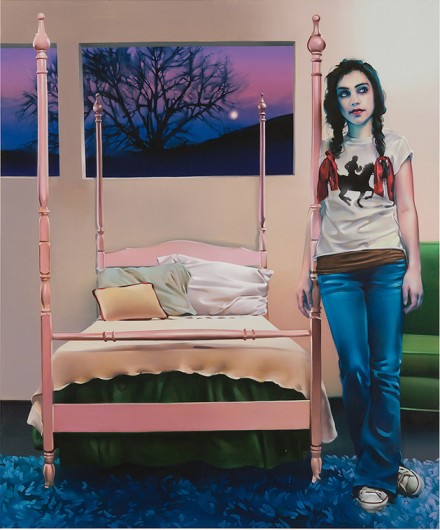

Rebecca Campbell

There is an enormous difficulty, in what is now an advanced stage of The Spectacle, of the administered and dominated totalitarian world of modern capital, in discovering this thought. The erasure of experience is a primary artery of the capitalist system of the 21st century. Art is quickly absorbed into ideology. So, there are areas in linguistic art forms, in image and in those mediums that combine both with movement, and in works of technological reproduction. Mass reproduction, in which only those works in which form negates the first layer of meaning, the communicative layer, survive as non-disposible. Or put another way, in which the form works oppositionally, somehow, to the thematic structures of the narrative and image.

The hermetic and difficult core of aesthetics here, following on Adorno and Benjamin (and to a degree Heidegger) is that this form of thought, the non-identical expression that does not “communicate” is also indecipherable. It is this riddle, this mystery that consitutes the meaning in a sense. Or rather, more directly, the experience. Here is where one runs directly into this contested and difficult notion of archaic truth content. It is both individual, in a partial or limited (but still significant) way, and it is historical.

“The true language of art is speechless” Adorno.

It is maybe clearer to think of it as undecipherable. It is a confrontation with the artwork through a recognition of the form that negates the top layer of meaning, and which privileges the non-communicative narrative of the archaic. I have always sort of thought that “narration” was the missing element in Adorno. For image narrates as well. Music narrates because the subject is a mimetic creature. And while language reaches the non-communicative, so often does narration. It is just that this non-communication is always part of a process. It is the narration that piece by piece discards meanings.

Matteo di Giovanni, detail, 1452

“”it is as if art works were re-enacting the process through which the subject comes painfully into being”” Adorno.

In a culture so driven by notions of identification, and by the artist’s intent –and intention is the cornerstone of almost all creative writing programs as well as painting and performance, this is a uniformally rejected idea. One’s intention, as artist and as audience in a way, too, is paramount. I intend to write a play about the plight of the homeless. It doesnt matter what the artist intends. The artwork that survives the ideology making process of consumption is the one having little to do directly with the intentions involved in its creation. The appearance of the artwork, its phenomenological being, links–by way of its non communicative self — the individual with the collective. This is the memory traces Benjamin writes of. I believe that in the narrative, the mimetic is directed by the contours of the form of the artwork, to the collective memory that is so antithetical to consumer capital (shopping is best done in a state of forgetting). Benjamin saw mimetic memory reconciling the individual with the collective. I think it is the narrative mimetic activity that actually does this. Today, as language is increasingly reduced to glyphs, and sound patterns, and to reductive commodity associations of tone and child-like feeling, the speechless is inert. Marketing tells people what feelings to have. Today, the refuge for experience is in cultivating the mimetic narrative. That cultivation is found in radical form.

Vincent Desiderio

In novelists like Peter Handke, for example, the narrative as such evaporates, and the mimetic engagement is forced, or directed down into sub-categories of story, or fragments of story, and the truth experience is in this struggle, which is always also a failure. The reader is left to examine ‘where’ he or she is left. This is the incomprehensible that must be taken in by the subject. Lost is a rediscovering. Today, the degrading of language is found in social media, where cliche and abbreviated thought is a given, and in propaganda from the state, and in the officially validated best sellers and hit movies churned out by the system. You cant get lost if you never go anywhere. Violence is the short circuiting of narration. Violence is the short circuiting of everything. The constant intensification of violence provides a stoppage, a blanketing of the experience of engagement.

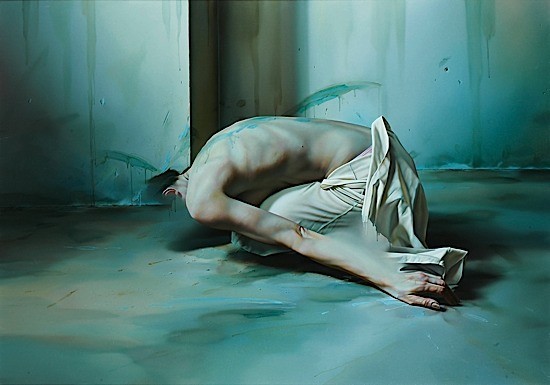

Istvan Sandorfi

So an Odd Nerdrum IS in fact just what he says he is. He is Thomas Kinkaid impersonating Velazquez and Rembrandt and Goya.

Taking collective shelter in the “realistic” and the “hopeful” or “optimisitc” is a form of surrender to the dominant smiley face totalitarianism of global Capital. Art that privileges the non-experiential is the art that is rewarded. It is either propaganda for the state, or the art of good intentions. The art of correct politics, and of correct ideology even. The song of the birds is a siren’s song unless one hears the shrieks of the predator behind it. For that shriek is a warning. Nerdrum though, is taking the idea of crap seriously. And for that, something has to be said.

For the predator in the animal world is not a false promise, but a truth. As a part of nature it is wholy unsentimental. It evokes the mortality of the subject. It bespeaks the narrative, ineluctable and inevitable, of archiac realities. The shriek is a threat and it is a fatalistic recognition of suffering. That life is suffering. That no rewarding resolution lies at the end of a yellow brick road (painted by Madison Avenue). Archaic mimesis is dis-enchantment. It is the negation of the Bowdlerized kitsch story telling of advertisiments, and the false shrieks of formula drama that pretends to seriousness of intention, or to the post modern renouncing of experience, in favor of cool indifference of surface reflection. Archaic mimesis is dis-enchantment as the precursor to re-enchantment.

The dilemma is that none of us can (easily, anyway) access a world outside commodity capital, outside the reified world of social domination. Our own dreams are colonized. Our own psychic formation obscured and re-packaged under a new label of therapy or individualism, or inner children, or some other kitsch creation that emphasizes a childhood that nobody ever had, but that many now feel guilt or resentment for having been denied. The material pain of poverty and racism and violence are all part of a vast apparatus of domination. For the priviliged class discourse includes substitute targets as enemies. The false collectivity of scapegoating is resurgent again. The master narrative pushes mimetic narrative from our dreams just as the return of the repressed does.

Bo Bartlett

Mimetic narrative has no message. It is a form of thought that reconciles subject and object and that produces authentic enigma. The cryptic mysteries of collectivity and history. Our own and society’s. Artworks meaningfulness is in proportion to their not being understood completly. And to their ability to avoid pandering, and cheefulness and its mirroring of the sales pitch form. But there is also the false incomprehensible. It is comprehended as “weird”, far out, or just as novelty. As innovative, sui generis, or just a catalogue of effects that signify strange. Such work always finds the expression of domination in one of its parts; in the rhythm of the voices, the repetitive beating on certain consonants, or the evoking of heroism in framing — even if this reactionary part never becomes the sum of the parts, or the whole.

Artworks are always events to a degree. They are actualizations of enigma, but not of the cheap kitsch UFO variety, which is the commodified story of sexual repression tricked out a tale of frustrated longing. Tabloid mysteries are only repressed sexual longing being re-branded as human interest or social investigation, but that only serve the sublimated pressures of life under the sign of the Spectacle.

The artwork must not sell anything, for selling is anti mimetic, and the reverse of mystery.

I started by mentioning Odd Nerdrum, and with some thoughts about figuration in painting today. With the inevitable fatigure that comes from an art scene that is really, just a niche market for financialized capital. There was an essay from Steven Shaviro, over at E-Flux, and count on Shaviro to embody something of what is so very depressing about theory and arts today.

“…Kant says, that I can enjoy sublime spectacles of danger. Beauty in itself is inefficacious. But this also means that beauty is in and of itself utopian. For beauty presupposes a liberation from need; it offers us a way out from the artificial scarcity imposed by the capitalist mode of production. However, since we do in fact live under this mode of production, beauty is only a “promise of happiness” (as Stendhal said) rather than happiness itself. Aesthetics, for us, is unavoidably fleeting and spectral. When time is money and labor is 24/7, we don’t have the luxury to be indifferent to the existence of anything. To use a distinction made by China Miéville, art under capitalism at best offers us escapism, rather than the actual prospect of escape.”

Why does beauty presuppose a liberation from need? The most needy cannot handle beauty? But wait, lets continue on a bit more…” Aesthetic experience is not part of any cognitive mechanism—even though it is never encountered apart from such a mechanism.” Well, here is a genuine problem for a lot of this brand of neo-leftist. The experience, call it aesthetic experience, is in fact congitive. It is processural, too, and this is why leaving aside the mimetic, and the narrative results in the post modern meltdowns of Hardt and Negri in a sense. At least applied to aesthetics. To art. And I do not see how those two are seperated. Now, it is true that financialized capital, in the current neo-liberal fascist incarnation, extracts value from everyone all the time. Social-capital, the shadow of this subsumption hangs over consciousness. However, there seems a rather significant flaw in Shaviro’s thinking on aesthetics, and it is this; the aesthetic is not only or just imprisoned in the commodity. It is true everything is gets bought and sold (all the more reason to resist as much as possible) but when one suggests moods and feelings are being capitalized, the truth is that only manufactured moods are. That is not to say our lives are not colonized by Capital, but it is only to the degree that one transfers these feelings to brand affinities. The point of view of this thinking is almost that of those who manufacture commodity junk.

Shaviro’s accelerationist aesthetics seems to be suggesting, lets make bad art even worse. If we can revel in the sheer magnitide of the violence and lurid exaggerations of pure exploitationist banality, then at least we won’t be dissapointed by the false hope of the idealistic work of quality. . There is an odd sort ecumenical posture in this. Somehow, there is the suggestion that such extreme junk may grant us a Kantian dispensation of indifference.

Let me be clear. The false optimistic fails, but not for the reasons Shaviro (or others in this edition of E-Flux) suggest. Again, the narrative is ignored, and the mimetic process as well. The idea, as Patrica McCormack puts it, that capitalism is consuming and digesting the “now” only begs the question…. What is the “now”? I mean these are sort of word games. And these essays all describe an area of elite white art making. It is geek culture in a way, the privilged version of Star Trek conventions. It is the institutional pov. The world of galleries and institutions and museums. And, of course behind all this, like the great wizard of Oz, are movies. The world of movies is the final frontier for critical thinking on the arts, it seems. But what I find most problematic is the equating of utopian, or a work whose ambitions extend beyond the idea of just describing cultural decay, with seriousness defined as ephemeral. False optimism leads, actually, to the same betrayal of the experience as does the validating of junk as somehow a political gesture. Beyond that, the writing of this stuff is self parody. Go ahead, and tell me what this is all about:

http://www.e-flux.com/journal/greyen-a-history-of-local-operative-criticism/

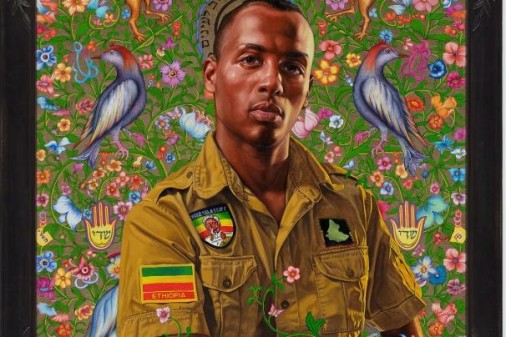

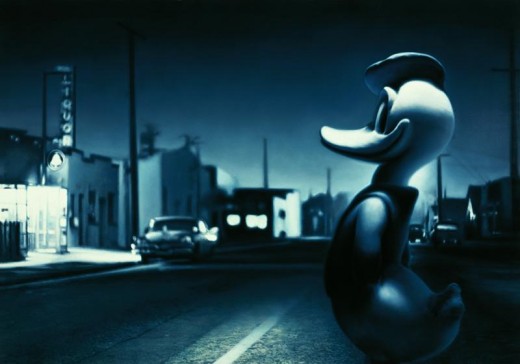

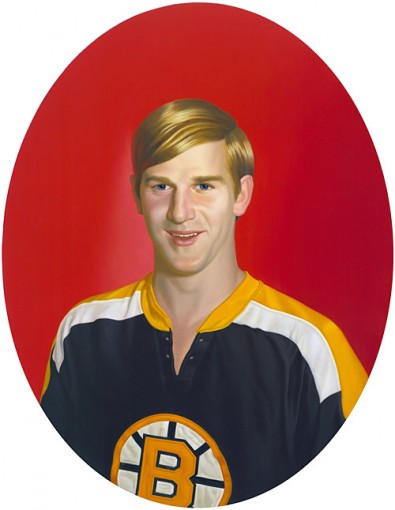

Kehinde Wiley

Now, the rise of a new traditionalism (realism) in painting should have been predictable. What I find curious is that it seems to be taking two paths, or perhaps three (actually, like twenty but….). One is the Nerdrum strain of a self conscious aping of the “great masters”. The second is the cheesy glossy and highly ironic illustrations of a Kurt Kauper. And lastly there is a sort of new classicism…Antonio Lopez Garcia and the redemption of realism. Now, I am not trying to lump everyone into these narrow defintions. A Jenny Saville, one of the Young British Artists, is well aside all this and perhaps really finding a valid practice, albeit rather limited. But there is also a very conservative and suffocating quality to a lot of work I see in the new figurative painters: Bo Bartlett, or Brad Kunkle, or Graydon Parrish, or John Currin (who is acutally not even trying to be anything more than sarcastic). Nerdrum has at least the virtue of greater technical facility than most, and a kind of carnival barker mysticism that imbues his work with a genuinely unsettling quality. Nerdrum can most certainly capture something uncanny, but one doubts if this intuition leads further. What seperates Nerdrum from a Garcia? The former’s technical facility is asking for response. Garcia is avoiding the response. He is asking (if he is asking for anything) for restraint. For time. This sort of monastarial quiet is far different from the noisey attempt at ‘quiet’ in Nerdrum. Garcia’s gravity though, finally, is imperious. And it is that slight tremor of disdain that haunts his work, both in the sense of awareness, of Goya, and in witholding. The witholding is something Nerdrum might learn from. A Rebecca Campbell is by intention a very modest painter of very minor work — but in some of her better painting achieves a bright sort of removal of feeling, like a shot of novacaine.. What a Adrian Ghenie will look like in twenty five years is unclear. Right now, it feels like a scavanging of other, earlier, artists and all thrown together with a set of effects meant to distract from the basic emptiness of the work. There is the white guy posturing of a Gregory Crewsdon, whose photographs serve as imitation hyper realist paintings in a sense (and oh, quelle surprise he lists David Lynch as a primary influence). The work of LA’s F. Scott Self is like a lot of this work, essentially illustration tricked out with “weirdness” effects. That said, at least Self is a good illustrator. And at least he has genuine humor. There are others, however, that are discovering a questioning of the realistic, Vincent Desidorio, and Istvan Sandorfi, both deflect the obvious sense of realism, and rather look to subtract anything corny or sentimental, and discover the fragility of what is just taken for granted. It is not always successful, but it is usually compelling. There are also a host of painters not strictly realistic, but figurative, doing conclusive authoritative work: Luc Tuymans, Martin Kippenberger, Daniel Richter, Michael Borremans, Marlane Dumas, Neo Rauch, and going back to Anselm Kiefer, and Gerhard Richter. All of these artists resist the idea of the real, of realism per se (and not a few are shown at David Zwirner’s gallery in the U.S.—along with R.Crumb). But there remains cross fertilizing with neo expressionists and a lot of *almost realists*.

There are dozens of others. One quick mention however on film. I saw Paul Schrader’s new film, The Canyons. Now, I found only one good review and that was in the New Yorker. What accounts for the highly negative reviews and audience reception to this film? How is it that a Terrence Malik is greeted with such reverance but Schrader’s new film with such anger and disdain? How does this relate to ideas of realism that Nerdrum raises? Well, one must always start with realism, the construction of an ideological ‘real’.

Dan McCleary

Again to return to Adorno — if we can access the particularity of an artwork, then the approach by definition has by passed the concept of the artwork. This becomes sort of Adorno’s specific anti Kantianism but it does relate to both Heidegger and Benjamin (and Freud and Lacan) in that it is the “unfamiliar” which allows for a mimetic engagement with the particular, which is, if it is particular, is also engimatic. It is also linked to the “uncanny”. The processural aspect, the sustaining of a tension, the duration of the mimetic, is obvious in theatre, and perhaps a bit less so in painting and photography. However, again, the mimetic IS partly a processural engagement everytime it occurs. For without that duration, the enigma is left inert. Without the narrative to hold duration, through an unfamiliar form, the enigmatic becomes cliche or formula. And formula is by definition familiar. And it is here that the uncanny, either in performance or form or color, or shape, creates a particularity. And that paricularity is the path to collectivity. In a Malick one gets a concept of the ‘real’. And further, you get a concept of a ‘serious real’. The world of a Malick does not draw one in, as it draws one to the concept of inward going. The experience of that *place* is missing.

Art imitates itself — is a paraphrase of Adorno, and I believe a misreading. This imitating, so various critics say, provides itself with autonomy by refusing to reproduce the mediated reality of domination — it provides ‘possibility’, a suggestion of an other potential. It is in that sense Utopian. Now, I believe the Utopian part. Art’s ‘message’ is always reactionary. If there is a message, it is reactionary.

In Schrader’s new film, the narrative seems to be secondary to the sense of meditation, of an almost religious perversity that pervades the narrative. The technical side is almost naive (in the sense Bresson is naive). By hiring James Deen and Lindsay Lohan, Schrader essentially brought semi trained performers for the camera. The “acting” draws attention to itself by not participating in this ‘real’, which is less the real of the film but the ‘real’ of studio product. The acting is anxiety about acting. Malik’s real is the same real as 60 Minutes or Breaking Bad, or Nike commercials. Those constructed ‘reals’ might all contain their own visual vocabularies, in terms of editing and camera placement, etc, but they are all from the same manufacturing schematic. When one watches Schrader’s film, the sense one has is that the text (Brett Easton Ellis) is not the focus, but rather the sense of place. The sense of a historical cultural place being dissected and laid out on specimen plates for later viewing. It is as if a Botanist were doing field work for white Southern California, and more narrowly the world of middle range film producers. It is, however, not really anything like The Player, although in one way it resembles Day of the Locust, in the sense that a sort of delerium accompanies the pursuits and dreams of everyone. The chimeric sense of fame or the desire for adulation. The scene when James Deen, as Christian, sits with his analyst (played by Schrader) is almost the perfect psychoanalytic dialogue on making a movie. And yet, its not about making a movie. It is about the anxiety of those reaching for approval. What is it to be a star? Deen, a porno actor making his serious acting debut, is reaching for the respect of art. Schrader is the almost Mabuse like puppeteer.

The Canyons, dr. Paul Schrader, 2013

In fact, that desire is really Schrader’s subject matter. For it is joyless and so reified and still born in all it’s expressions, and the film lingers long enough for discomfort to congeal in almost every single scene. It is not a film with a message (such as The Player), but a film that cataglogues what “message” might really mean anymore. And if all messages are put in turnaround? You end up with this. And the violence feels purely psychic. It is in this that the film’s particularity resides.

The melodramatic that one finds in a Nerdrum, or in a lot of figurative painting, even if its tricked out in pseduo ‘blankness’, is the same set of conventions that Sirk worked with, and later Fassbinder. The sense of narrative is that of reduction, simplification, and this is largely the world of Madison Avenue, and of US politics. Reagan and Nancy, Barack and Michelle, these are controlled melodramas predicated on the manufacture of a specific emotion at a specific time.

Bush Jr.’s melodrama was more a Western. Clinton a sort of rom-com, but etched against the backdrop of elite schools and an overcoming obstacles story.. prestige achieved for the bumpkin from Arkansas. That Hillary was always so almost grotesque probably made the Monica story a necessity to reach the level for melodramatic. In Sirk the melodrama is given the same sort of X-ray treatment that Schrader gives to the careerist autopsy report of The Canyons. But Sirk was never really part of the manufactured ‘real’. Nor is Schrader. I might argue, again, that nothing is accepted as commodity by the public if it deviates from the manufacturing code for real. The most common complaint from the provinces, about movies or theatre is “that wasn’t believable”. Nobody even knows what they mean when they say that. Believe what? That it’s a movie?

Wittgenstein said an interesting thing, that ‘understanding’ is not just a mental feeling. That other feelings like confidence or familiarity are present….as “more or less characteristic accompaniments” to understanding.

Gottfried Helnwein

I believe a good deal of the problem with aesthetic criticism today is that it is non-experiential. Culture is read to prove points, or stake out positions. This is true on both the right and left. The difference is that the left recognizes that the status quo is a ruthless system of racist inequality. What seems missing though, is the potential liberation within art. That liberation is cultural, personal perhaps, but by extension it is the development of sensibilities that then learn compassion, awareness of the world around them, and the value of the human. And that critical reaction, when reflexive or un-experienced, will often fail to hear the echo of jack boots or the slamming shut of detention camp doors that hide behind the song of birds, for the song by itself is sentimental. Within many good intentions often lie bad art, and bad in very totalitarian ways.

Antonio Lopez Garcia

The level of aesthetic criticism today, even in what are thought of as leftist journals or sites, is stunninglly STUNNINGLY childish and ahistorical. But I addtionally wanted to mention that I came across a number of articles on film and film writing. The subject of auteur criticism came up and almost without exception there was a hostility toward the Cahiers critics. I think this is mostly due to, firstly, that aesthetics lag behind other critical writing and theory, and that secondly, because of this there is a marked reductionism and political conservatism being expressed.

Here is a quote from John Hess on the climate of French film culture in the early 1950s.

” It also took the form of a radical advocacy of art for art’s sake, a forceful return to the standard bourgeois conception of art as autonomous and out of time. For example, Eric Rohmer praised films such as Hitchcock’s STRANGERS ON A TRAIN, Renoir’s THE RIVER (1951), and Rossellini’s STROMBOLI (1949) because they were “out of their time enough to date less than others, but thereby better able to express the malaise and hopes of their time” (26, p. 18). Truffaut saw Wilder’s STALAG 17 (1953) as an “apology for individualism’s and asked his readers to praise all films which show that “the solutions are in us and in us alone” (28, p. 54). These four films’ told the story these critics valued—that of the individual’s personal salvation which consisted of a rejection of social values and concerns in favor of spiritual insight. Obviously these critics identified with these heroes and heroines who, in effect, rejected the world—they too, as disfranchised intellectuals, were painfully aware of their own solitude morale.”

Civilian observers, A bomb test, early 1950s.

Edward Hopper, 1960

This isnt quite right. Rohmer aside (because who knows what Eric Rohmer thinks, or thought), the Cahiers critics were NOT de-politicizing but quite the opposite. They were however, trying to think dialectically. And even withhin that quote there is the sentence that ends…”…of their time”. Meaning, it is not by direct means that symbols and allegory aquire their power. But it is through the concrete and not the generalized. A symbol does not begin as a symbol, it only becomes symbolic within a narrative. But for the early Cahiers writers the focus was on “film”. On how narrative worked on film. Bazin was indeed an old fashioned Catholic follower of Mournier, and I’ve never thought he really exerted much influence after a certain point. But for Rivette and Godard and Truffaut, the question was in what ways did the camera comment — or capture something — by montage, by tracking shots, by deep focus, or just the essential framing choices. The mise en scene. And partly, the auteur theory was stating that every performance was about the actor’s choices and every film was about the director making his film. But, it was never not clear that every film was also lodged in concrete reality, and that objects and people were being filmed in an historical moment. My basic point here is that when Rivette or Godard write of Elia Kazan as almost unique in his ability to direct actors in a manner that will reveal their nakedness, their own drama, under the character, they are not suggesting the usual mis-reading of Stanislavski, in which empathic identification if the highest goal for the audience, but rather that the uncanny and transcendent ONLY occurs at a stage after the performative is recognized as performative. So once again, the assumption that drives these misreadings is “realism”. It always always is. It is assumed that somehow, film (and theatre, and figurative painting etc) are there to render “reality” as well as possible. While in fact, what Godard knew and Rivette (after Artaud and Dreyer and Rosselini) was that film is a ceremony, a ritual, not a documentation. And that, the paradox is in a sense, that to perform that ceremony one must perform the role, on stage or on film. That performance is not attempting to be ‘like real life’.

‘Oh that wasn’t believable….’. Nobody knows what is believable. WHAT is believable? Is it believable that the US military dropped TWO nuclear weapons on civilian Japanese cities and incinerated hundreds of thousands of people? Is is believable that King Leopold decimated close to half the population of the Congo while enslaving nearly 100% of it. Or that he cut off the hands of the children of those slaves who tried to escape? Is it believable that the US has a prison complex larger than any in history? What is believable? That a plane flew into the Pentagon? That DARPA is developing secret climate weapons? I mean, modern society runs on an engine that constantly reiterates the idea of realistic. Of believability.

The ‘role’, a part, is a ritual enacting of text. It is not pretending to be in ‘real life’. What IS real life, anyway? The daily existence of life in this system of humiliating and dehumanizing labor is the control of existence. It is actually the destruction of life. Is standing and refilling the soft ice cream machine behind the counter at McDonald’s, wearing a dorky uniform with a name tag pinned to your chest pocket, is that real life? Is sitting inside Florence Colorado’s super max joint without the lights ever being turned off, in a tiny soundless cell, is that real? There is a puritanical masculinist sound to the very term ‘real life’, and it is expressed in the theatre of humiliation and stigmaitizing that is reality TV. Telling people to ‘get real’ or the demand for realism is all the same. It is the sound of the Marine drill sergeant, the patriarchal Church elder. There is only life, and it is less real all the time.

Aesthetically, in a film or on a stage, the ceremonial works out a logic that is related to but not identical to the material world around us, as each of us experiences it. And collectively, as a society, we know certain things. We collectively know them. It is simply the undeniable agreement we share with a large convincing number of others. An in a sense, it is our ‘collective knowledge’ that is attacked first by this system of capitalist domination. The collective has its underpinnings kicked out by the destruction of traditional learning, but the encouragement to trust in the atomized knowledge of research science, and by the dismantling of community. In an ever more reified culture, the individual is left to shop for who to trust. Or just to obey orders. One used to trust neighbors, and strangers in public places easily enough could stand in as neighbors. Today I think people trust the TV and media and they trust movies. And increasingly they obey this media apparatus. Even if they claim not to, they do. What once society knew collectively, and shared, they now no longer trust.

But back for a second, to the idea of auteur theory, realism, and the misreading of aesthetics today. And to the Adorno theories of aesthetics. The backlash now against auteur is because it demands too much filmic knowledge. Ergo, its a bunch of cheese eating surrender monkey bullshit. Realism is the dominant construct. It is part of the identity construct. Ideas such as ‘identification’ have to be articulated against the given backdrop of realistic. And, finally, I happen to believe that Adorno’s life project of working through the difficult terrain of mimesis and how to splice in Marx and Freud, ended with his unfinished masterpiece, Aesthetic Theory.

“Emphatically, art is knowledge, though not the knowledge of objects. Only he understands an artwork who grasps it as a complex nexus of truth, which inevitably involves its relation to untruth, its own as well as that external to it; any other judgement of artworks would be arbitrary.” Adorno

One must understand Lopez Garcia’s sober gravitas as possessing grandeur, but only fully if one sees an imperious arrogance lurking at the edges of each carefully worked canvas. In the painting above, the oil and dirt stained street is foregrounded. It is rendered with such conviction, greater than anything else in the painting. The untruth of the arrogant authoritarian restores a gravitas to realist painting by squeezing out a grace that is this humility, to work out the stains before all else. Hitchcock’s untruth was a deformed misogyny which was transferred to male characters as often as female, and an often pandering desire to be liked in his embrace of formula narratives, but which only served to more starkly reveal the uncanny and troubled sense in his films of both individual and collective anxiety. What is popularly called suspense in Hitchcock was a secret torturing impulse that is born of sexual repression. It is revenge on the form itself. In Hitchcock the sane society is a lie. There is an untruth to theory itself. The appeal in aesthetics to realism is akin to the appeal in philosophy to universal thought. Realism is also, always, the echo of hygenic denial and repression. It is a sensibility for tough and virile, like black coffee and working on car engines.

Kurt Kauper

If art is cut loose from the intention to objective truth telling, to the material world around it and to history, it then becomes simply what you have in most corporate product. A simple stimulus inducing amusement park ride. Albeit one that has propagandistic uses. You have only films about other films, and about other films revisionist presentation of history. I saw an episode of “Copper”, in which a black character (in post civil war New York) speaks of Lincoln. What he says is lifted almost totally from the Speilberg film. And so movie *history* begins, and becomes *history*. In a recent several episodes of Magic City, set in 1950s Miami, the Cuban revolution is treated as if Castro had STOLEN the island from Cubans and drove them away to Miami where they had to work as dishwashers at big hotels. The constant claim “oh its only a movie”, or “its just entertainment” is always applied to film and TV. Nobody says, ‘its just a painting’. *Oh its just a photograph’. Why is this? It is because distraction is sacred in this culture and film and TV are the mechanical priests, or the alterpiece for distraction. Distraction is carried out in realistic terms, however. The better to believe in your distraction. History is now a sampling of distraction.

It is important, I believe, to sharpen the critique of artworks beyond either moral instruction of the left, or the solipsistic crytpo fascism of most post modern infantilism, or the naked deaths head degeneracy of offical Pentagon propaganda.

Henry Giroux wrote recently:

“The American public needs more than a show of outrage or endless demonstrations. It needs to develop a formative culture for producing a language of critique, possibility, and broad-based political change. Such a project is indispensable for developing an organized politics that speaks to a future that can provide sustainable jobs, decent health care, quality education, and communities of solidarity and support for young people.”

Empty activism is just the imitation of an industrial Fordist repetition of movement. The development of this culture as Giroux suggests it, the development of a language for critique that is not the private solipsism of post graduate programs, or the infantile mush of so much post modern gonzo babble, means taking aesthetic resistance seriously. It means culture is to be treated seriously. Organizing and demonstrations could take on the vision and quality of a raised awareness, or historical knowledge, of dignity, and so begin the formation of community and shared life, that has been stolen by the fascism of the US state.

John, so much to process here, I don’t know where to begin. I’ll start with The Canyons. Watched it on the big screen yesterday at the Sunset 5 and was immediately taken by the images of the run down, abandoned theaters across the country featured in the titles. Uncanny all on their own, they warned the audience that this film hails from a style of cinema that no longer exists. The titles announce to the world that there is no theater where a film such as this would run, unless somehow it is “sold” as something else. Interesting that you bring up Bresson in relation to the acting. The anxiety of acting, very interesting observation. James Deen’s pouty tough-guy put on. Lohan wanting to be likable and sexy. The anxiety. That’s what comes through in an unsettling way. The acting is so affected, so self-conscious, that it strips itself of all realism and achieves something spectacular. I was affected by it and I still don’t know why.

The film gives off a quality that reminds of me shooting day for night. It’s not that the scenes were dark themselves, but the quality of the video somehow dimmed the luminance of the picture, flattening out the space to make everything off-kilter. The scene that comes to mind is when Lohan is lunching with the assistant on the Sunset Strip and the big brown UPS truck comes toward them in a terrifying way, flattened against the space, so it seems that the truck is only inches away. I bring that up because the naive techniques of the film reflect the flattened lives of these characters, the acting style, and the quality of light.

By the way, the shrink was played by Gus Van Sant (not Schrader – although a stand in for Schrader), whom I actually sat beside at an Italian restaurant in Los Feliz two weeks ago… which adds to the whole strange experience of watching The Canyons. I recognized all of L.A. in it, but here it was different. It possessed that dream-like quality, uncanny almost, as if I had been there once, but maybe not. I think the same goes with James Deen and his career as a porn actor. To intertwine this “actor” within the narrative, an “actor” whom many of us have “seen” before, usually naked, on smaller screens, on the internet, late at night, and now he’s obsessing over Lindsay – it’s kind of a mind-fuck. And you’re so fucking right about Ellis’s script – the text – being the sense of space, especially compared to Malick’s whispered platitudes (and I don’t dislike Malick’s films).

haha, thats so funny I did this weird brain glitch about Van Sant. I mean i know what van sant looks like…as i once hired tim streeter for a play…the star of Mala Noche.. In a way you’re right, he was playing Schrader, though. Funny too that i remember that lunch scene on sunset and the UPS truck. The scene passes without comment, although for a second the audience thinks of some other genre, of catastrophe. That the truck will collide with the two women calmly eating lunch. The entire film is unsettling in that way. And your comment earlier about it being a B movie thriller isnt exactly wrong…that is the subject of the film, the climate for raising money for these entertainments. And the desire for recognition, for applause. It makes sense that critics hated this film. It does nothing to flatter anyone connected with the industry, nor does it flatter fan – audiences to feel reassured somehow about the world. All the perfectly crafted offices, all the exhibition of ‘taste’ and coolness and decor of the moment. Its a memorable film.

and let me add, per the uncanny. Yes, it’s a very dream like film. The conversations in scenes never seem to end, or even begin….you drop in on them, and they all feel oddly disconnected, and yet not. You arent even sure what you just heard. Like a dream the sense of time escapes your grasp.

so much here

just wanted to say its really absorbing

and thanks for identifying the art its evocative

i dont even know where to start but how about here

‘There is a need, and Adorno was for his entire lifetime, working to analyse this, for culture and art to access an archaic stage of our being.’

Hi John,

Just came across your essay (actually through a search of Nerdrum images!). What you write is interesting to me as I’m making a return to figurative painting after years of abstraction. And Odd Nerdrum is fundamental to that return. Why? How long do we have?!

There are some great painters in the world – virtuosos of their medium, with great orchestral instincts and powerful interior vision. There are also many painters who are technical virtuosos, but with little to say. And there are a great many figurative painters who seem oblivious to the riches of their medium and are in fact, in a state of hostage to the photographic and digital realms. They are the ‘hyper-realists’, or those aspiring to be such. Nerdrum, Kieffer, Barcello and their ilk belong to the great painter category. They are formidable on every level. For oil painters they speak a language of substances which only painters can truly appreciate. Far from ‘aping’ the Old Masters, painters like Nerdrum (there are sadly few) master both composition and oil paint (why not simply bask in it?!!). Nerdrum does not simply take from this tradition, he gives it new life, through his own ‘uncanny’ compositional vision (and what more has painting ever done?). This is irrespective of questions of figuration vs abstraction. What is really at work here is the mythos, which the three painters I mention articulate through inarticulate substance, vs the logos, represented by painters of cool, conceptual and hyper-real values, such as Kauper. At least, this is how I’m seeing it! I guess this is where I found your survey incongruent with my own understanding of painting. It is a big subject, with many perspectives I guess. But I think we do a disservice to our art forms if we are not discerning enough: painters simply do not fit easily into figurative and non-figurative categories. And the Kaupers of the world are on a different aesthetic planet to the Nerdrums of the world! It’s also interesting to note that both Nerdrum and Kieffer counted Buoys as a mentor! Ah, the mythos…

thanks 🙂

thanks you !