It’s all the same, just a little bit different. Jean Luc Godard

It’s all the same, just a little bit different. Jean Luc Godard

There seem a whole host of issues this week that are coalescing for me in terms related to my interest in aesthetic resistance…an effort to deconstruct aspects of the cutural production of Empire, for lack of a better description.

The sense of social hypocricy was formed, as we understand it today, in the 18th century. The idea of acting one’s role in daily life pervaded the culture of that time. The viewer or audience and his or her relationship to the performance, or artwork was solidified, in a sense, around the time of Diderot and Goya. Theatre came to focus a good deal on social hypocrisy, and one’s private or inner self came to be seen as more real or authentic than the “role” one played in public. The idea being one doesn’t have to lie to onself (sounds quaint these days).

Questions of mimesis arise here, and I’ve written a bit about this already, and will again, for it’s central I think to understanding how art can reclaim some validity in everyday life.

For Rousseau, the actor was a deceiver, skilled at the counterfeiting of oneself. Diderot however, seemed to argue that in fact, what the actor did was only whatever everyone did in their daily social life. They presented a certain picture of themselves.

Interestingly, Diderot thought that the best actors were the one’s who had no real feelings. Who had trained themselves to suppress real emotion. Quite a bit later Stanislavski would contradict this, and later still Lee Strasberg would form a practice that insisted on actors finding the “real” feelings of their character. It is well to ponder here, how this evolution happened, and why, but more importantly, to gauge its effect in today’s surveillance state, in a world of reality TV and social networking. A world of interrogation and lie detectors.

Its useful to think on Brecht for a moment here as well. The Brechtian principle of performance was to undercut traditional Aristotelian notions of identification, which would simply reinforce a passivity. However accurate this may or may not be, what has taken place over the last sixty years or so with the advent of technological mass culture is to commodify the image of the performance, and thereby double down on its passivity-effect. Political life is now performance. It is also branding. Facebook is self advertising, and self branding (it is other things, too, of course). I suspect that the power of the hegemonic dimensions of mass culture have foregrounded the master narrative in ways never imagined, and therefore sort of subsumed the power of any particular performance. This suggests to me that artworks, films or plays or TV shows, that manage to re-work that master discourse somehow, even if only by finding image and narrative that counter the prevailing sensibility — for its never just story or an individual actor — are the ones that acheive a kind of resonance. I wrote earlier on this blog about the uncanny in performance. Those performances that somehow destablize the seamless implementing of this invented everyday reality.

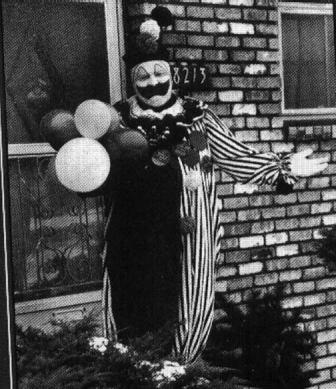

Both Brecht and Beckett loved circus clowns. So did John Wayne Gacy, but maybe that’s not important. Artaud of course wanted to shatter all conventions of the presentation of self. All these impulses are related for they all work toward the effect of the uncanny. The clown wears a mask, a literal one. In Indian Kathakali, the painted faces and masks are codified to express emotional states or feelings already understood by the audience in their familiarity with the known legends and myths being performed. General Petraeus acts out a tragi-comedy of public disgrace that is really only part of his well crafted image as patriotic warrior. His face is its own mask, of course. A clown mask to be sure. His face more and more looks as though it is painted on.

General Petraeus

It stikes me that the advent of film and TV has eliminated the mediator that exists in live theatre. That mediator is the ritual space created by a collective audience seated together, and not in seperate rooms across the planet. Audiences may sit together in film theatres, but the missing live actor renders the attention less acute. Whereas in theatre there is no attempt to deceive the audience that this is reality, the camera subtly implies a documentary versimilitude to all narrative. It does imply a fooling of the viewer. The edges blur between news camera and cinematic camera. A show such as Homeland, ludicrous as it may be, still presents itself as somehow real. As an almost documentary in one sense. This is how it really is. Theatre can never even attempt that for live actors stand before a live audience and quotidian space is transformed by this focused attention into a ritual space. A ceremony takes place. That ceremony may even be a bourgeois narrative about daily life, but it retains some small element of the allegorical anyway. TV and film does not, unless great effort is made by the filmmaker to create alternative readings, an alternative sensibility.

Bullhead, a first feature by Belgian director Michael R. Roskam, glosses several genres but undercuts all them by really narrating the male body as sacrifical steer, a brutal violent beast like victim of the daily abuses of capital. The manufactured masculine. Of that borderline poverty of the usually unseen modern Europe. It is interesting that critics have come away unsatisified often because of their attempts to understand or search for a message that isn’t there. This becomes, almost by default, a deconstruction of bourgoise police dramas. I can think of only a few films in recent memory that do something similiar (Audiard’s remarkable and maybe masterpiece un prophete [A Prophet] or Escalante’s Los Bastardos).

Today the relationship mimetically between corporate entertainment and the viewer has clearly shifted. The sense of identification has changed. For its no longer simply identification, it’s a form of enclosure, of co-opting grammar, gesture, and ideology all at once. If Goffman was right forty years ago that all daily interaction is acting as an effort to communicate a message of sincerity, then the absorbtion of Strasberg’s principles of ‘real’emotions in perfoming a character have come together at the level of used car commercial. Kierkegaard once asked if we can ever know when we are being sincere. Goffman says at one end of the sincerity scale is the con man, who performs cynically, and at the other the US Marine who believes in his duty. It would be easy to imagine a public of con men but in reality I suspect more people “believe” their roles, only they no longer know what “belief” quite means. One also suspects an ever growing number of people living under the shadow of the Spectacle who don’t believe it at all, but have trouble tweezing apart the bounderies of cynicism and sincerity.

The rise of Irony in post modern artworks has provided cover for the anxiety of not knowing. The ideological put down, the cyncical pose of know it all seen it all world weariness, the too hip posture have come to be shelter from the mimetic terror of the real reality which is the reproduction of relations of exploitation. The reproduction of Capital.

The role one is demanded to play at work is a role sanity demands we believe…to a degree. We are, as Goffman wrote, audience and actor at our own performance. There are clues to be found, though, in mass culture, to how tenuous this reality. The trend toward “behind the scenes” segments of fan and gossip film programs reveals the anxiety hidden in the blurring of everyday and TV or film. Come behind the scenes at the lastest James Bond movie. Part of this is the sense bestowed on the viewer of being special, but it’s also the reasurrance that these are just plain folks, workers, who are no different than you or I. It’s all the same —isn’t it?

There is far more to say on this, in particular about how notions and definitions of realism have evolved. The Spectacle assigns roles, and today’s ‘attention economy’, the valorizing of image — in its circulation, and the ever deepening self branding that occurs, at least in the West, around social networking, has bred new anxieties, if not new pathologies. As a genuine post modern police state forms…as the fall out from the giant commercial of electoral politics starts to be felt, real contradictions will inevitably rise up in the performance of daily life. The world is ‘acting’ differently.

Somehow, to learn to recognize the counter narrative, those cultural works that redfine the outlines of daily life, that allow glimpses of rarely seen points of view, those artworks that assault the bourgeois values and beliefs, through their radical form, rather than message or theme, that graft familiar genres to new narratives, and image, will come to seem ever more important for sanity.

Very intriguing. Coming from a family of actors, I was always taught to exploit the most out of a scene emotionally. Especially in theater. But this always felt false to me. The greatest actors withhold their emotions (especially in cinema) and they also seem to embrace the “unknown”. I wonder if strasberg and his ilk are to blame for the current state or devolution of acting? Or is it the fault of an oligarchic media behemoth?

I reckon in the long run, the Strasberg influence has had a negative effect. Some of his disciples were headache-inducing hams (Rod Steiger?). And the most striking – like Monroe or Brando – are still so unnervingly ‘odd’ that I think the ‘method’ routine was a very minor aspect of their greatness anyway.

Particularly since the 80s, the (mostly male) stars who try and ape the ‘brooding, intense’ method routine have been cringe-making more often than not. It seems to have segued into a kind of Wal-Mart Charles Laughton now – endless ‘pretty boys’ struggling to be seen as ‘men of a thousand faces’ with dopey voices borrowed off pop stars and make-up that melts into the CGI. A galling trend now is playing up “ethnic intense” from movie reference points instead of any lived reality (and this applies to all ethnicities – Denzel Washington in ‘Training Day’ sucked as much as much as any Mafia goombah schtick borrowed from De Niro). Or worse – embarrassing themselves as ‘retard/cripple of the month’ in a desperate bid for Oscar nominations. Harold Russell wasn’t even a professional actor – and he conveyed his character with much more skill and conviction than any of these ‘a-listers’.

This is so complicated, Jack . But I do think Strasberg’s influence was unfortunate….it was easily aped in cheap ways, and probably ended up producing its opposite. I think the complicated part is defining what we mean by emotions, vis a vis an audience in this post modern world. I think all of that has shifted a good deal.

@kasper. Totally true i think regards Brando and Clift. etc … I think brando was just sui generis anyway. In all things.

Training Day is an interesting discussion. But too complicated for me to undertake right now …at least fully. I think i liked denzel better in that because he wasnt trying to be so fucking virtuous. That weird presentation of virtue you get with him, and its obviously mediated by his black-star-ness brand. Sidney Poitier became Denzel or something. So to see a mean spirited role actually appealed to me. Same in American gangster actually. But more to the point I think you are really onto something about pretty boy actors……there are legions of them today, and something happened to make them feel accused…..this defensiveness about their own beauty. A collective sense of accusation sort of floats around male stars now. I dont think Tyrone Power suffered that, or Errol Flynn. Its partly the puer eternus thing I mentioned. A general infantalizing of the culture in its images of sex attraction. Sophia Loren became meg ryan or jennifer aniston. There has been a trend toward the hygenic….a de-odorizing of sexual icons.

This in turn is linked to definitions of masculinity. And the uptick in a sexual violence. The role of sexy has shifted a lot….maybe more for men even.

Interesting you mention Power – one of my favorites is Nightmare Alley, where he doesn’t fight against the submerged creepiness (or coldness) of his ‘pretty boy’ persona, but exploits it to the hilt. Quite a few other actors did similar until the 80s (or effortlessly amped up the weirdness, like Brando). Another thing is that they visibly aged. Some could do that brilliantly without any physical change – like Pacino over the course of two Godfatheer movies. Leo Di Caprio still feels like a teenager doing ‘J Edgar Hoover’ or ‘Howard Hughes’ for a school exercise. When he leaves prison at the start of Gangs of New York, he should look (or at least behave) like Brendan Gleeson, not a ‘heart throb’. And Johnny Depp has become increasingly unwatchable the harder he tries to play Pirate of Rochester or Hunter S. Wonka or whatever. I expect the ongoing vogue for British actors is that their faces still accumulate lines, fat etc. (and they’re cheaper). The grubbier expressions or ambiguities aren’t ironed out as much.

But Denzel in Training Day – I dunno, it felt like such a pop-inflected 2-D simulation of “badass black guy” it didn’t convince at all. A performance that wouldn’t be out of place in a Tarantino movie really.

Yeah….@kasper:

the age thing is fascinating actually. And love Nightmare Alley. And Power is perfect for exactly those reasons.

But UK actors today are simply better. I mean across the board…on more or less every level you can think of, and even in a show like Homeland, the only three decent perfomances are british actors. Im not sure what it is exactly, beyond the fact they tend to do theater, because they can make a living in the UK doing theatre. In the 40s, american actors came from other lines of work………….but today you are sort of groomed either at the university, or as child actors, or models.

@Kasper, great thoughts. Man I love Harold Russell in “Best Years of our lives” It seems to also take a great director to be able to allow a life not imposed to come out. I would imagine directors are a great deal different in Europe than out here. Man, it’s really discouraging to see nearly all directors in LA serving the master on set. Especially for TV, a director is the bitch of the show. Wasn’t always like that.