I am noticing something of late, culturally speaking. I cant say I at all fully understand it, but I can offer a few observations.

It seems that US culture, film and TV, is now so influential as to constitute reality. History has become the history of movies. Mention the name John Foster Dulles and it seems, from this present generation, you will likely see blank stares. Mention Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and you see their eyes light up. Mention Pinochet or Lumumba, or Suharto……….you get very little reaction. Mention NYPD Blue, people will have a reaction.

I’ve written on a lot of this already and there is a lot more to say. However, I want to focus on a few specific examples and make a few, brief comments.

Australian film the last seven or eight years has been very impressive. Even before that you have Paul Cox and the early Peter Weir. However, look at Weir’s Australian films….The Last Wave, and then look at his Hollywood work..Witness.

What is the change? What is the difference?

It is to look at these changes that we see something of significance I think (culturally speaking).

Recent films from Australia worth looking at:

Noise (2007) directed by Mathew Saville. This is a favorite film of mine, I have to say. It sort of conforms to most of my beliefs about the practice of film writing. It is also worth seeing what is NOT in this film. A highly elliptical crime film, of sorts, it’s more a meditation on both genre and on the sense of modern alienation. (Interesting there was another film with the same title made that same year, as well as one made in 2004).

Little Fish (2005) directed by Rowen Woods. This is a curious film, but Cate Blanchett with her working class Aussie accent is very good I think, and Hugo Weaving oustanding. As heroin addict films go, this is quite unique. But mostly it captures something of the banality and repetitive tedium of immigrant life in Sydney. Woods did a film of some value in the late 90s called The Boys.

Animal Kingdom (2010) dircted by David Michod. This film developed a following to the point where it’s probably a bit overrated at this point. That said, it contains as powerful an opening as I can remember in recent memory.

I might add The Square as well, Nash Edgerton’s 2008 crime story. Its as if James Cain had written about Perth or suburban Sydney.

Paul Cox, who has made a number of fascinating low budget films, deserves some mention for Man of Flowers (1983) a sui generis curiosity that has stuck with me, however, for years.

Now, what is it that seperates these films from most of US *independent* film? I think the answer lies in a basic lack of manipulation. I recently tried to think of my favorite US films of the last year. One would be Texas Killing Fields directed by Michael Mann’s daughter, Amy. You probably haven’t seen it because it never got a distributor. Soderbergh’s Contagion seemed of some interest, as was We Need to Talk About Kevin and Drive, of which I’ve talked about earlier in my dialogue with Guy Zimmerman. There are maybe a couple others. I can tell you what is NOT on my list, Tree of Life, and Shame. I understand the reception to both those films, but I would argue in ten or twenty years, both will seem hopelessly self conscious and infused with a dopy poeticism and pretentiousness. But no doubt the best work in the US was Todd Haynes HBO mini series Mildred Pierce. Based on the classic James Cain novel, Haynes created perhaps the most complete filmic vision of the year from any country. The fact that the reception to this series was, at best, lukewarm, should come as no surprise. The pace was glacial, but the sense of place indelible and so suffocating in its grasp bourgeois sensibilites, as well as its concrete honesty in depicting working class struggles, that it didnt appeal at all to an audience trained on The Sopranos or Mad Men. The aesthetic judgement of today’s U.S. audience is mediated by this ‘picture of the real’ I have tried to describe earlier on this blog. That picture is expressed via a certain dependency on naturalistic performances and more, on the reinforcement of a landscape created in accordance with the dominant narrative of life as defined by the U.S. state department and Edward Bernays, probably. The police state apologies of network TV for the last forty years, and the erasure of working class realities, an almost religious attachment to technology as the savior for mankind, and a climate where the final solution (as well as definitions of masculinity) reside in violence all serve to define the current state of culture.

Now — before one gets into debates with *fans* out there, allow me to say that if I were to make another list in six months of my favorite films of this year, it might well be completely different. That’s because firstly, one is always in the process of redefining the criteria and re-thinking artworks in the light of societal changes and in the light of subsequent work by any particular director.

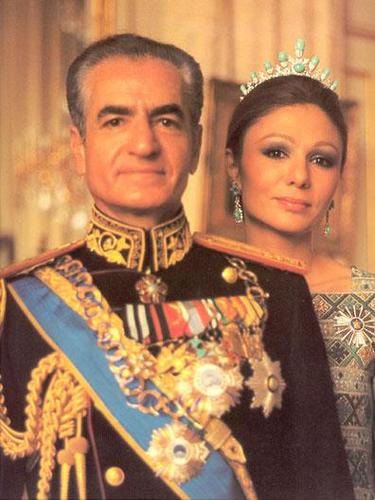

It’s not a question of what anyone *likes* — I suspect we all like weird things because a particular piece of work, a film or TV series, triggers very personal mimetic decodings….and all of that is legitimate in its way. But if one steps back and says, OK, what am I looking at? What is on the screen there? And what does this narrative do, what does it this image do? And then try to examine the prejudices and ideology behind it, the results can be very disconcerting – but also revelatory. I happen to love Lawrence of Arabia, I love O’Toole and I love the cinematography, and to see that film in scope, in a theatre, remains a singular experience. If I have to examine it as a narrative of colonial history, I am met with real contradictions. I wont get into a discussion here about T.E. Lawrence, but I think you get my point. There has been a lot of writing of late on Breaking Bad in the blogsphere…and a kind of blowback has set in. I want to write an entire entry on this series soon, but for me, the crack like addictive qualities of that show seem the result primarely of the way its shot — and it is shot amazingly well. Its almost Wellesian, and it imparts a grandeur on the narrative, it mythologizes banality in much the same way the Cohen Brothers often do. And the dizzying effects of the freshness of its image tend to obscure a highly problematic presentation of race, the DEA, and white masculinity. But as I say, thats for next time perhaps. What I hope to say here or ask for here is to start an examination of why so much US film and TV feels as if it is drawing on ONLY earlier film and television. The cadence of the speech, the archetecture of the shots and the editing, and certainly the depiction of the accepted terms of daily life all feel as carefully enclosed within the terms set out by previous film and TV. The political life of the US populace is now enclosed within these terms as well. Obama is the guest star of a reality TV show set in the White House. History is erased. Political debate is restricted to celebrity talk show topics. Drone deaths, justice department attacks on civil liberties, and the execution of almost certainly innocent men are subjects not breeched. History ….the history of Kissinger, Chile, Central America and Haiti, of Duvalier and Arbenez and Milosevic are not ever brought up, let alone a historical framing of Iran. Do we ever hear of The Shah or SAVAK? No, of course not.

A film I both love, and feel ambivalent about is Escalante’s Los Bastardos (2008).

I saw this film in Trondheim, Norway, at the festival there, and at 11 pm. I left the theatre in an altered state. It is a singular achievment, no matter where one finally decides it belongs in the canon. If you ask me today, I say its a masterpiece. The only other film in the last ten years I can say that about is Audiard’s A Prophet. But there are a handful of directors whose work I am always going to rush to see; Audiard, Dumont, and Escalante. I probably would add Haneke, too, though so far I really haven’t felt the films succeed at all. Yet….I know I will go see the next one because the project Haneke is working on is serious. At the very least.

However, I don’t want to do a favorite’s list here. I want to start a dialogue about what culture is doing and, really, if art is even possible anymore. Adorno said:

“For absolute freedom in art, always limited to the particular, comes into contradiction with the perennial unfreedom of the whole. In it the place of art became uncertain.”

In an ever less human society, in an society ever more under a cloud of mass manipulation, the sense of autonomy once taken for granted has become unclear.

Still, art seperates itself (if it is art at all) from the material and empirical world in an effort to create an alternative. It will always have that capability, regardless of social domination. However, as the populace falls ever further asleep, ever more sonambulistic, questions are (by default) raised.

So, as reality seems increasingly enclosed within a film strip, as the unconscious more resembles a repository of out-takes, and as public discourse contracts to terms laid out by corporate “entertainment” I think it is worth attempting a close reading of film and TV in an effort to provide an autopsy or post mortum reading of the post modern psyche. Why do we react the way we react to certain film & TV? If I suggest that Val Lewton’s best work is vastly superior to Malik’s latest bloated self indulgence, what are the terms in which that can debated?

Today, if you ask me the greatest of all film artists, I would have to say Fassbinder. Of all directors, all filmmakers, he remains the most resistant to co-option somehow. Others obviously come to mind, Pasolini and Buneul, and then those whose importance perhaps exists outside their actual films — Godard maybe. Why does Army of Shadows (1969) seem so amazingly vivid today, perhaps more than when it was released, what are the ways in which that happens?

http://www.criterion.com/films/153-army-of-shadows

Today we must look forward to Kathryn Bigelow’s coming atrocity on the killing of Bin Ladin, Zero Dark Thirty. A double bill with the Melville would be a pretty fascinating evening.

Thanks for this post, John. Interestingly, I watched Nick Roeg’s Walkabout with my daughter recently and I was astonished by how conservative the medium has gotten since the 70s. Just on a formal level so much has fallen away, and it really does echo the general suppression of expressivity and what might be called surplus desire. David Gulpilli is astonishingly young in the film and literally straight from the outback where he was a famous tribal dancer, and Roeg is smart enough to feature a gorgeous dance from Gulpilli. But every movement he takes is a kind of dance – part of a song line, an embodied geological expressivity. Gulpilli became the iconic aborigine, appearing in The Last Wave and The Shout by Skolimowski, for example. Depressingly, he has apparently been through the ringer lately, drinking heavily, putting on weight and appearing in court on charges of spousal abuse. It’s a tragic arc given his great beauty in the Roeg film, one that finds parallels in American Indian figures in our own culture. In any event, Walkabout is wonderful.

You’ve been talking about Los Bastardos for years and I still haven’t seen it. On my list now. In terms of the Haneke, I really did think the White Ribbon had a lot going on, including some of the most uncomfortable scenes of psychological cruelty. If you ever wondered why the Nazi fever seized Germany, The White Ribbon has the answer.

I think things are shifting back to the left now, but such dark clouds on the horizon, no? I went to a Chris Marker retrospective the other night and one of the standouts was his “Remembrance of Things to Come” about the years in Paris between the two wars. A few moments were astonishing including a long shot of Marcel Duchamp gazing into the camera with such awareness in his eyes of what was fast approaching…I’ve been haunted by it ever since.

Guy Z.

Guy, Im glad you mentioned The Shout. Skolimowski was the probably the best graduate of the film school in Lodz…where I taught….yet gets little love from his home country. The Shout remains something special, and when you see it now one can feel the energy of that period. Its a film that defies so many conventions and Bates performance is just pitched exactly right somehow (worth noting that Deep End is very good, too). I cant imagine The Shout today, although Noise is in a sense the descendent of that film, and others from that era. I singled out australia for I feel those B projects are all part of a collective upsurge of creativity there. In a way Noise would be the perfect double bill with The Shout. Noise is The Shout filtered through several decades of rightward lurching…..a fixation on police and their role in everyday life.

The Shout is a film that I would resonate more today than ever. For too many reasons to list.

Hey John, how funny you post this now. I’ve been debating writing about my favorite films last year but haven’t found a way to write about them other than how much I “liked” them. This gives me a some ideas to work from.

I’ve been wanting to email you recently about having seen both Los Bastardos and Texas Killing Fields, back to back actually. The interesting thing – at least for me – about those films is how the shadow of Mexico completely saturates both of them. Both of the worlds in those two films feel like they’re bursting at the seams as they’re straining to keep Mexico-US relationship off-camera. The violence against women in Mexico (all the rape and murder recently) is a topic I’ve become obsessed with since reading Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 so it has obviously colored my interpretation of Bastardos and Killing Fields – but still – the violence is there in those films, lurking, and the great id of Mexico, the dark shadow of the south, infiltrates the repressed lands of the US. Texas, Southern Cali. The scene that sticks with me from Los Bastardos is when the group of rockers throw the can of beer at the younger Mexican boy’s head. His reaction is purely an immigrant reaction – wanting to lash out but afraid.

You and I will disagree on several films (Tree of Life, Shame, Melancholia) and that’s fine. Tree of Life may seem like a self-indulgent affair looking back at it now, and perhaps it is, but I don’t believe it comes from that place. Mallick has turned his back on Hollywood for the longest time, he refuses to do interviews, go to awards shows, even have his photo taken. I think his film is a sincere attempt at examining the fractured state of American men his age and how the idea of compassion affects them. The parents lose the sensitive child in the war, the Oedipal desires of the oldest son are clear against the iron-fisted father, but it’s all so meaningless, a speck, in the lifetime of the planet and God means. Yes, the film has problems. Certain people have a problem with the complete lack of irony in his films, I get it, some of the “poetic” dialogue is cringeworthy, but the cinematic impact of the film somehow balances it out.

I guess this leads me to ask you this: how do we separate the emotional impact a film has from the culture it examines/criticizes? When does the cinematic impact of a film not live up to its content – which is how I felt about Texas Killing Fields, in regards to the how the film was made. The reverse side of that is Melancholia when the cinematic mastery of images obviously carries so much weight that the content of the film can’t quite live up to it.

Good notes, Joe.

First here is a piece I wrote on Melancholia a while back.

http://www.culturalweekly.com/latency-von-triers-melancholia.html

but I would love to hear more of your thoughts on both those films. I think they’re worth discussing. As for Malik……..I know Im probably in a minority position on this. And in some respects I admired Tree of Life. And it wasn’t until about two thirds of the way through it that I began to lose heart. I mean he captues the sense I had…as a boy…of that era. And its resonant…..but somehow it all slowly ebbs away. The narrative isnt elliptical or mysterious, but flat. I began to think, well, shots of dinosauers is an interesting choice….the cosmos made literal in that opening…..but it felt just like bad poetry to me. I dont dimiss malik, although last time I saw Days of Heaven, it seemed a lesser film than even I had remembered it. Lots of “nice shots”….but again, in the service of a very banal vision. I dont get if Malik even thinks of the world around him, really.

Los Bastardos is a difficult film to write about, at least for me. Its operating on so many levels. That Mexico functions as the surplus Id is absolutely true……and what I thought so interesting about that was that it was coupled to an implicit critque about a marginalized class. That coda is startling…..and very moving and disturbing. The film looks at our crimes from so many perspectives. State oppression, exploitation, and the personal drama — the inevitable violence at the heart of all these dynamics. Its very much laid out as an allegory, a parable, too, and a vision of the truely disturbing nature of modern life. And the pathologizing effects of poverty. From that opening long slow shot of the two workers walking in the LA River…to that coda….its a remarkable film I think.

As for texas killing fields………..its not ambitious in the same sense at all, but it does provide this canvas … much like los bastardos……of a pathologized society, one where violence against women has been moved to a position of magic thought…..oh, its just that demon infested region where we dont want to go. The willfull mystification of the police –even the ones who care — as its mediated by religion and institutionalization. I really have to see it again, but I remember being very surprised at how effective it was, and how haunting.

It could be useful to examine both these films against the ‘accepted’ thematic treatments of stuff like the Marvell comix blockbusters, or even some of the more widely accepted indie stuff…..or prestige television….Boardwalk Empire and Mad Men…both of which are period and hence fetishizing set decor — in a way I havent been able to articulate yet. But it does suggest to me how narratives that on the surface resemble texas killing fields (which is not unlike those post viet nam noirs on one level) or los bastardos, how these more accepted mainstream films appropriate the structural fetishizing of mad men, to contemporary landscapes….making of the modern landscape a de facto period landcape.

I completely agree about Los Bastardos. Reading his bio, I actually feel a kinship to Escalante (born in Barcelona to Catalan parents, living in Mexico, studying in Cuba). I think he understands the alienation of immigrants that comes with being a foreigner in his own country. I think Los Bastardos is the more effective film. It knows immediately what kind of film it is and doesn’t strive to achieve mainstream appeal. It feels like an immigrant operating outside of social/cinematic conformity but it holds a mirror up to the culture. The other scene that sticks with me is when the older Mexican goes down on the white woman. It speaks to the fetishizing of the other. To these Mexican men, this huerita is “exotic.” It’s interesting what he DOESN’T do. He just goes down on her, pleasuring her. There’s a reverence in his actions that I find disturbing because I don’t think he would go down on a Mexican woman the same way.

Texas Killing Fields felt like the work of an interesting young woman, despite her Hollywood connections, whom only knows how to operate under certain cinematic norms. The style/form of her film is more mainstream, which I feel prevents her from making the statements that galvanized her vision. Just look at the cast. But that’s why the the film is interesting to me – it’s stuck in a “no (wo)man’s land” between two aesthetic worlds. And that’s the beauty of it, really. But even through that, Ami Mann’s voice as an American woman comes through.

Let’s see what Mann’s next move is. Maybe she’ll succumb to the pressures to make a more mainstream film or maybe she can figure out how to work subversively within the system. Sofia Coppola and her last film “Somewhere” come to mind. I think Coppola realized she’d never break outside of the shadow her family has constructed for her and she wants to destroy it from the inside.

A actually very good submit by you my good friend. We have bookmarked this web page and can are available back again following several days to verify for almost any new posts which you make.

Arika Foxx

I often use Esmokeless myself. My wife like them. They are looking to get more.