Richard Billingham, photography.

“Deep contempt and indifference to the spirit is a trait of the ideal type of the modern bourgeois…”

Max Horkheimer

“Nowadays, the moral efforts of the intellectuals are no longer directed at the owners of the means of production, but at the members of the lower classes, who are being bound against their interest to the whole. This change has meant that influential members of society now treat intellectuals with disdain, regarding them as servants and entertainers whose activity is of no relevance to the lives of the powerful.”

Heinz Steinert

“The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.”

Guy Debord

“Great shame and sorrow of that fall he tooke;

For neuer yet, sith warlike armes he bore,

And shiuvering speare in bloudie field first shooke,

He found himselfe dishonored so sore.”

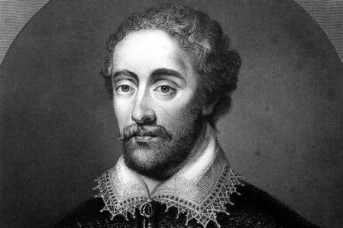

Edmund Spencer, The Faerie Queene

Book 3, Canto 1, stanza 7

The effects of TV, and now of internet, more than film, create an idea of access to an *inside*. Heinz Steinert wrote; “Political journalists have become *insiders*, and they are treated as a kind of courtly entourage.” But it goes beyond this, for the nature of screen image is to establish a world that the viewer can own, and a world that bestows a specialness on this viewer. The viewer is invited inside the residence of this ‘world’. The viewer is a VIP guest. I suspect that this constitutes and shapes a good deal of what is expressed as *populism* today. And as this new *home* has grown, so real homes have shrunk, in concrete social terms. To be invited backstage on the new Mily Cyrus tour is a lot more exciting than being invited to your friend’s house down the block for a christmas party. The growth of ‘Reality TV’ shows is testimony to the fact that there is now a population accustomed to a view of the world set against the backdrop of this idea; in other words everyone can get a backstage pass for almost anything.

The sense of passivity found in large chunks of the population (speaking of the U.S. and parts of Europe) is the outcome of viewing politics as a personal personality quiz. There is a cynicism that results. Politicians are not viewed hugely different than Real Housewives of Atlanta, or Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, or even The West Wing. The endless stream of banality that makes up 95% of reality TV establishes a sense of familiarity for the viewer. Their own lives are full of banality, too. I wonder if people today talk more than in earlier eras? Did people chat this much in 16th century Italy or France? Or in the time of Chaucer? I don’t know, but if they did, their conversations were different. Today there is a kind of chit chat that constitutes a disposible language. It is neither personal, nor work related. Nor is it critical or pedagogical. It is an empty sound intended to echo through the halls of people’s private backstage. But there is, additionally, the endless stream of disposible image that runs from the candid photos of celebrities, to the video of reality TV, to cell phone snapshots. All of it is transitory, and barely really examined in any conventional way. It may be that the lack of deep emotional response to the torture photos at Abu Ghraib, or the various dashboard videos of police misconduct fail to gain traction because they can’t really be differentiated from all the other endless image and noise that is circulated daily in the West.

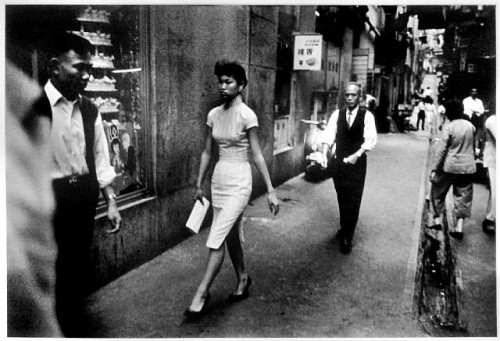

Ed Van der Elskin, photography. Hong Kong.

The erosion of a critical vocabulary, or more, a vocabulary that registers heterogeneity, has seemingly made it ever harder to express seriousness. The rise in corporate media coincides with a growing criticism of the working class. This the right wing pundit syndrome that cites the poor and workers for laziness, criminality, and a host of other character flaws. There is a paucity of answers to this from below, partly because, in the U.S. anyway, of the fetishizing of *individuality*. Rather than answering as a class, and critically dissecting social domination, the answer is too often framed in individual terms. There is hence no shortage of stories about some singular individual who bucked the odds and found success. Those odds are rarely even examined.

Edmund Spencer

Heinz Steinert’s very good book Culture Industry makes the point that, per Marx, that criticism must always work with the conceptual tools of domination. The loss of cultural seriousness is rarely addressed in the post modern epoch. Among the most insidious of the these tools is an unseriousness that has become attached to almost all discourse. The rather admirable Hyperallergic online art magazine made a list of the things problematic in the art world. Its one of those end of the year lists. But there are only a couple of items I might take issue with, the accumulative effects of reading it is to sense the lack of seriousness overall in art today. http://hyperallergic.com/170748/the-20-most-powerless-people-in-the-art-world-2014-edition/

Richard Artschwager

And this is directly related to this manufactured populism. And to capital, as is everything I think. There has evolved an assumption that goes something like ‘this appeals to a very small number of people, therefore it is elitist and conservative’. Well, in fact, this democratization of arts and culture is fairly recent, as ideas go. And I have never been sure that a wide audience is necessary or even desirable for art. Art is not there to foment revolution. Its purpose, as I repeat endlessly, paraphrasing Adorno, resides in its purposelessness. From the autonomy born of this recognition, one can begin to forge an emancipatory vision, and to create works of art that provide experience, stimulate dreams, and I dont know what else. But that is important. However, it is not something the majority of people are going to have an interest in. More people might, under a better education system, but not a majority. Its like martial arts. I’ve known genuine masters. Guys who have practiced for fifty years. Old men. They have devoted everything to this study, and a monk like existence. That is not for everyone. Not everyone wants that, or can do that. But its magnificent that some can. Great artists are rare. Great poets, playwrights, anything. Rare. Valuable. But not everyone wants to read Spencer’s The Faerie Queen. I read it, but I didn’t exactly enjoy it. I appreciated something in it, in its influences, in the language. Mostly in the density of syntax and the sound. You should read it aloud I think, in parts anyway. That sound matters. But it’s also a tedious exercise to pour through this very long book, a poem of 800 pages. But that is part of the deeper reward in work that demands a good deal of the viewer or reader or audience. There are artists that if you asked me do I *like* them, I would say yes. With qualifications, but yes. But what does it mean to *like* an artwork. Someone like Amy Feldman, a very talented painter I think. Talented and facile. Not very deep. Very close to decoration, but I still *like* Feldman. If I lived in a cabin with a Feldman on the wall I would not go crazy with the tedium of it. And that I consider a compliment. If I was to use Alberto Burri, or even Anne Truit, I would say there is something more demanding in each of them, and perhaps especially in Burri.

In theatre, a Pinter say, is not really entertaining. His plays are demanding. But that mimetic journey is the point, really, of all aesthetic discussions. Otherwise decoration serves as well. There is a relationship between artist and critic, and this has changed over the last thirty years. It exists, too, between the political and critic as well. Today, the critic is almost always, in part at least, a media critic as well as art critic or political commentator. Because nothing can be fully separated from the delivery system: media. So this is gradual ascendance of a media reality, one in which the audience, or viewer is flattered and made to feel special, to be an insider, mediates all criticism. Operations such as VICE for example, are pseudo journalism. They are really in the entertainment business. At the other end of the spectrum are the prestige outlets that cater to an educated and affluent class. And even arts institutions, museums and galleries and large theatres are involved in marketing and commodity tie-ins, and celebrity associations. All of this, whatever the principle focus of any particular campaign or event, has a secondary theme and that is self validation. The media critic is validating media. It is actually very hard to critique media without this affirmation taking place. But perhaps that is just unavoidable today in a world where media touches everything…and increasingly touches how we think. This has spawned an *attention economy*. Gradually this has taken the shape of a system that projects the image of a populist trend. Because the goal is sheer numbers of viewers, that which is being viewed matters far less. And work that is difficult, that by its nature is not meant to be engaged with by large numbers of people is more acutely marginalized than ever before.

Amy Feldman

People don’t talk about culture or art, they talk about *cultural services*. Culture has become something very close to a financial service. Ben Davis wrote 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, and in a very cogent review Adam Turl wrote; “What Ranciere does for political art is what Jean Francois Lyotard did for philosophy. Beginning with an exaggerated sense of the subjective–in art and politics for Ranciere, in politics for Lyotard–the subjective and objective are then completely blurred and their distinctions made meaningless. All this is philosophical cover for political retreat.”

It is not just political retreat, but spiritual retreat as well. Ranciere has, I think, a conflicted relationship to mass culture. And he is hardly the worst offender, and in fact often makes very astute observations and criticisms. But it is true that he is doing something not hugely different than Zizek does and that is foster a retreat AND then grant permission to embrace the mass manipulation of this marketed domination. This is why Adorno remains such a crucial thinker, and a target for media experts who decry his elitism. For elitism is now the fall back accusation for anything that smacks of criticism of this system of mass deception. Elitism is anything that rejects accessibility. This leads back to the topic of seriousness. For what I mean by serious is work that looks to overcome the inherent disposibility of most everything today. And it is more than just the appearance of the work, artwork, it means the entire trajectory of the body of work of a particular artist. And there are certainly contradictions in this idea. The first is that the fetishized notion of individual genius has to be both negated, and then absorbed. This is the dilemma of working with the tools of domination. Now, there is another concurrent issue, one of class exclusion. Social exclusion, and in the U.S. the lower classes and working poor, designated as less valuable consumers, are hence less likely to see themselves or their concerns reflected back at them. But this is also an advantage for without, as it were, a backstage pass, the marginalized population has the potential to be far more able to discern the mechanisms of manipulation, but more, to nurture a seriousness of vision. To what degree the poor are less influenced by media is an open question, however.

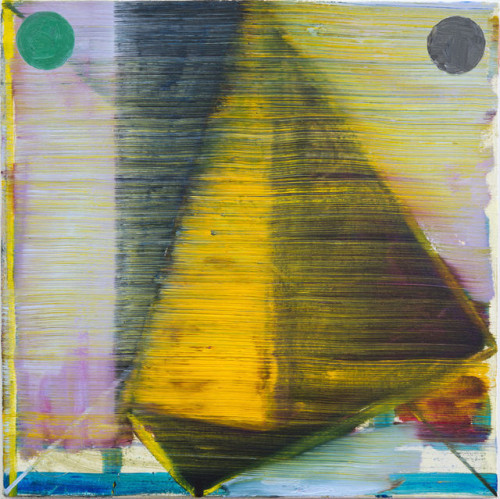

Phillippe Cognee. ‘Brasilia’.

If one sticks to painting for the moment, there has been a good deal of debate about *Zombie Formalism*. This mini-art war was started by Walter Robinson in an essay at Artspace last year. I quote:

“With their simple and direct manufacture, these artworks are elegant and elemental, and can be said to say something basic about what painting is—about its ontology, if you think of abstraction as a philosophical venture. Like a figure of speech or, perhaps, like a joke, this kind of painting is easy to understand, yet suggestive of multiple meanings. (Kassay’s paintings, for example, are ostensibly made with silver, a valuable metal that invokes a separate, non-artistic system of value, not unlike medieval religious icons, which were priced by both their devotional subjects and by the amount of gold they contained.) Finally, these pictures all have certain qualities—a chic strangeness, a mysterious drama, a meditative calm—that function well in the realm of high-end, hyper-contemporary interior design.

Another important element of Zombie Formalism is what I like to think of as a simulacrum of originality. Looking back at art history, aesthetic importance is measured by novelty, by the artist doing something that had never been done before. In our Postmodernist age, “real” originality can be found only in the past, so we have today only its echo.”

Lucien Smith

It is easy to dismiss contemporary painting because so much of it is so bad. But that’s also the response of the philistine. Much harder is to tweeze out the valid work from junk. Lucian Smith, a current darling of the auction scene is junk. It’s simply lazy, intentionally trivial, and wouldnt even make good wallpaper. In Smith though, it may be an end has been reached for a kind of socially adroit user friendly pandering gregarious artist peddling easily branded art designed as commodity first (and yes, useful in contemporary interior design). Smith and perhaps Alex Israel are the in some sense a truly toxic mixture of greed, superficiality, desire for fame. To follow the logic at work here, in the not too distant future a Smith or Israel or Dan Colon or Parker Ito will be commissioned to make *art* works that serve as exclusive head rests on the corporate jets of Goldman Sachs; superior craftsmenship, exclusivity, in shiny pastels and all signed.

Jerry Saltz wrote a piece here, which is quite good and in the discussion: http://www.vulture.com/2014/06/why-new-abstract-paintings-look-the-same.html

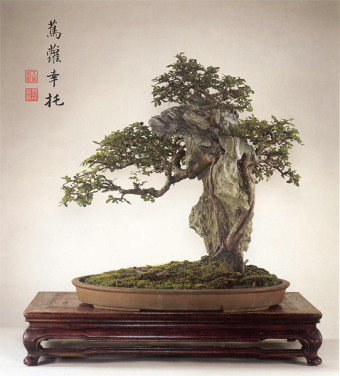

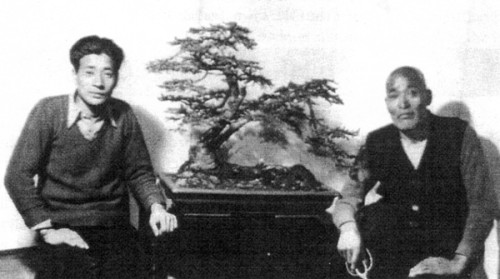

Ulmus Parviofolia. Chinese Penjing (Wu Yee Sun, Hong Kong).

But the Zombie tag is a snide dismissing of Clement Greenberg values, and while I’m hardly going to defend Greenberg much, he still was a man of some seriousness about art. But perhaps the problem with discernment begins with the mediation of galleries and curators and collectors; from Castelli to Saatchi the brahmins of the art market have distorted perception. One can value a Jered Sprecher for example, while still knowing this is the work of a minor artist. But I think its legitimate work nonetheless. The second issue is educational. It is daunting to suddenly walk into a gallery opening, or group show, if you’ve never thought about painting. This is why there is a tendency for many to resort of virtuosity as a criteria. So that Odd Nerdrum might be better received than Thoba Kendoori. Figurative work (of a certain sort, but more on that later) is, on the surface of things, a safer place to dwell, intellectually. The beauty of Marco Tirelli’s work is more elusive than George Shaw. But looking at Shaw, the uneducated eye (sic) is likely not ‘liking’ Shaw for the right reasons. And on the other hand, Nerdrum (and I’m largely sympathetic to Nerdrum on the whole) the lay viewer is likely not seeing what there is to dislike in his caricature of Renaissance masters. Now, the idea of an educated audience for meaningful, or *high art* came into existence, as we understand it, around two hundred or so years ago. It evolved as a sub-category of class marker. The bourgeoisie could claim superiority over the less educated (even if successful). Now there are differing ways to look at the idea of ‘demanding’, and they differ as well if, say, painting is examined as opposed to theatre or dance. That is a whole huge topic, and one that I will return to, hopefully, soon.

Opening cocktail reception; Whitney Biennial, 2014

But all this finally ends begging questions having to do with the society on the whole. That art has value is a premise I adhere to, and which I will try to elucidate here in some adumbrated manner. And I think aesthetic resistance is, in fact, of great importance today. But I continue to believe that the contemplation of the artwork far exceeds what is often a vulgar reductionism from the left, and an even more vulgar dismissal from the right. The right wing defenders of class hierarchy are there to mystify the production of culture in an effort to maintain the status quo. There is in all creative acts of any ambition a sense of search. Tom Huhn, in an essay on Kant and Adorno, says; “The sublime is not itself redemption but the persistent performance of the expectation that redemption ought to be at hand.”

For both Kant and Adorno, art was where a wounded (and repressed) Nature migrated. Or, rather, where the sublime migrated. This is really a dissection of subjectivity in the form of the modern individual, and in a sense this was seen by Adorno as the product of historical forces that *emancipated* the individual’s self awareness. In other words the ‘modern’ idea of self. This can certainly be debated, but for the purposes of this posting, I’m just going forward from that presumption. For the germane issue is the development of a disfigured subjectivity that was prey to the reification of modern life. That beauty (Nature) is the residue of the nonidentity of things that have been destroyed by a Universalizing subjectivity. In one sense this was the dialectic of Enlightenment foreshadowed. There was a promise in nature broken by the reification of the social — that in simply accepting the beauty that is given, we are betraying something not yet possible. In fact, Adorno comes very close to Heidegger when he writes of the subject’s too close proximity to the beautiful in Nature, where Nature will always conceal itself anew. But in truth, that proximity is itself a lie, and art is the realm or activity in which carries forward this tension between particular and universal; it bears the weight of this promise. The dreams and dreamwork of humankind are then embedded in art, and which accumulate historically, and it is in this growth of the autonomous that art realizes something of its impossibility. And this is why one of the discernments between meaningful work and kitsch is a self awareness of the artwork that the artwork always fails. Art that warrants contemplation is always an expression of the impossible. Art’s importance is as the repository of human freedom (autonomy).

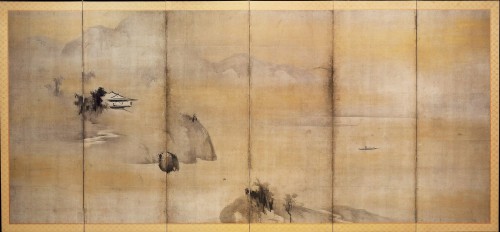

Kaiho Yusho, apprx. 1602

There is, though, the disfigured human. The political goals of genuine freedom require that something of culture (art) has to be included as a ongoing de-briefing of the subject. This is mimesis, or an aspect of it, anyway.

Those early communities of people, twenty thousand years ago in a distant past of great night darkness were looking at things and beginning some tactile and sensual appraising of the particular and this expansive just germinating idea of Universal. It is possible, also, that this germination was far more penetrating as to the great-time-continuum on which consciousness glides than is the contemporary man or woman.

Crypt area, beneath Ripon Cathedral, Yorkshire. (courtesy Angol Saxon Yorkshire).

Chair by Phillipe Hiquily

What needs to be remembered, per Debord and Adorno, is that marketing and PR do not operate in isolation, from each other or society overall. Their most profound influence is in a long term administration of desire and labor. The creation of, and control of social integration — as Steinert put it. But even he doesn’t probably go far enough by saying that. For the long range impact is in not just the creation of this faux reality, but in the erasing of unwanted experience. Unwanted by the producers of media, by the state, by global Capital. It is, also, often a process of substitution. Instead of the mystifications of Church idolatry, you get Kim and Kholoe or Angelina and Brad, or Barry and Michelle. As Adorno put it, the public today is captivated by the myth of success. And it only one of the myths that cast a strange spell on the population. This is, it needs be said, the more affluent workers, the bourgeoisie that have the leisure time ‘for’ captivation. I have found, on a personal level recently, that what I perceive as a desperation in the white population (mostly white men) overlaps with an aggression bound up with a *need* to believe the myth. The white man today KNOWS he is not manipulated, for he is too smart for that. And his success, the success he hopes for and strives for is to be learned by a through familiarity with the world and teachings of mass media.

These believers, of course, in their familiarity, are prone to imitation. For they feel their own image must match that which they are bombarded with 24 hours day. Keeping up with the Joneses means now keeping up with the characters in their favorite TV shows. The fact is that individual commercials or marketing campaigns are not fooling the public, but that doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter because seeing through the manipulation is their assigned role, and hence the great rise in cynicism and snark. It is an encouraged subjective posture. Snide is cool, and makes you …again…an insider. An insider where there is no inside.

350 year old Black Pine bonsai. Kunio Kobayashi, Tokyo. (K. Olson photo.)

The question that I always think is a bit neglected, is how is it that in varying ways, all societies create art. They create artifacts anyway, or shrines, or relics. They paint or draw something. They scratch on walls or invent complex processes to give image another quality from the ordinary. Whatever the ordinary is. It is a way to change reality. Children do it. Children spin in circles until dizzy — as a way to alter reality, an inner reality. Mind altering. Almost all children take pleasure in drawing. They are almost intoxicated with color and shape. I cannot imagine a culture or society in which something of this process isn’t going on. But it is capitalism, or the Church, or basic psychic aggression that changes that children’s impulse for joy into the Whitney Biennial, with underpaid servants scurrying around to refill the chablis, and little brie on bisquits for the rich and contemptuous in attendance. When I have read explanations for cave paintings or those neolithic carved stones, in shapes resembling jaguars or snakes, suggesting animism and religion and how this was crude imitation I am never convinced. It sounds wrong. It is patronizing and schematic and linked to some moronic idea of *progress*. People carry far more complex mental processes than that, and probably most of what early humans created is lost and not yet discovered. The Pharaonic Egyptians had already developed several layers of writings, sophisticated (if perverse) ideas about image and story and symbol, and the relationship to death, to violence and the sacred. Considerably more complex than modern European culture. The seductive aspect of certain materials; gold, and silver, and bronze, carry emotional associations. Gold and lead are heavy, and their weight seems unnatural, while glass both feels a friend and a betrayal somehow. Pottery, and screens, and wood, and endless qualities of wood, and the use of shadow and light on these materials, especially in Japanese and Chinese cultures. The Japanese and south Asian culture valued candle light, and roofs were gold fractyls to reflect the candle light. As Tanizaki made clear, the garish gold and reds and silvers of South Asian and central Asian architecture was meant to be seen by candle light, not electric light. Japanese aesthetics remains in some ways the most multi tiered, with a sense of the importance of not revealing things too quickly. Everything is delayed gratification. The fetishistic character of gold, to pick the most extreme and historically accidental example, doesn’t mean that somehow the artworks use of gold is invalid. In both the progressive and regressive sense, artworks are historically mediated.

Jered Sprecher

There has to be a dialectical aspect to all art, I think. In any painting, there is always a beauty that is dominated in the process of its representation, but which overcomes or transcends that domination by virtue of its objectivity. This is Adorno channeling both Hegel and Kant. That objectivity is, however, also reified, or alienated, depending on a host of factors, and must reconcile itself to this alienation, but then illuminate in its aspiration to the sublime what is otherwise unseen by humans. The paint, in the Sprecher above, in those little circles, is set against the movement of the brush stroke (or sprayed application) and distances itself from the composition in its essential color. One’s eye returns again and again to those circles; one teal and one grey. Now, after that the viewer is essentially activating that inner karaoke, and this is how mimetic process plays out. But it also says something about history, and the allegorical aspects pregnant in any artwork. Sprecher’s painting is not overly complex, nor is it overly emotional, or intellectual or anything. But it retains a kind of elemental integrity, and there is a sly intelligence to the color. An infirm yellow is the central figure here. It is not a yellow of spring or of canaries, but one of pestilent infestation. The teal is, perhaps as teal shall always be, a sort of profligate slightly middle brow color and it serves this painting very effectively. Now, one could go on and try to (and should) look at more of Sprecher’s work. There is a lot to discover. How substantial is this painting? I don’t know yet. Nobody does I don’t think. It is hard, though, to say the same thing about Lucian Smith (or dozens others). There is just nothing there. Its like shopping for bedsheets.

This is where the importance of the uncanny sort of intersects with mimesis.

My point though, is that one has to be able to see what is alike about Sprecher or Toba Khedoora, a 350 year old Bonsai black pine. I can’t tell you, but I know in some transcendent realm of ur-mimetic respect the great one-mind of existence is revealing something and I suspect we just dont get it yet.

Paintings become much like a Maserati or Patek Phillipe watch, or bespoke St Crispin loafers, or a private jet. Lucien Smith or Alex Israel WANT their work to be used in the decor of private jets, in fact. But this value system affects everyone. The artwork becomes a bespoke wall fixture, and nothing more. So I return to the bonsai masters again and it becomes clear that those bonsai projects are not commodities in the usual sense. They are expressions of personal vision, but they are also long term projects often lasting beyond death of the first artist, and more, they are part of a strict set of principles and rules about form. History is incorporated in them much as the crypt at Ripon accrues sacred value. They are a practice and a craft as well, in which the individual is not reified or commodified. The *artist*, the bonsai master, is only the conduit through which something comes into being. And it is in that respect that he aquires a seriousness.

Saburo and Tomekichi Kato with Ezo Spruce. (Photo from Thomas S. Elias).

“In contemporary art, the greatest value adding component comes from the branded auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s…What do you hope to acquire when you bid at a presigious evening auction at Sotheby’s? A bundle of things: a painting of course, but hopefully also a new dimension to how people see you. As Robert Lacey described it in his book about Sotheby’s, you are bidding for class, for a validation of your taste.”

Don Thompson

The professionalization of art is serving over the last fifty or sixty years to neutralize its oppositional character. Art may not exist in a rarefied realm free of class tension, but it exists differently within that class system. That said, the values of the dominant class confer a special character to specific creative endeavors in any particular period. The ownership class not only designates who has value among various artists, but it designates who and what doesn’t. The artist must be amendable to the court, or at least serve as a novelty, but must never *really* offend. The rise of mass electronic culture, mostly in film and TV, has resulted in a merging of this new false populism (which is its opposite, in fact) with fine arts. And all of it increasingly merged with marketing. Through this entire evolution of a marketed reality the autonomous character of all art forms has eroded. This is probably the most pronounced issue with contemporary culture; how to reclaim some portion of autonomy for the creative act. Certainly it wont be found at the Whitney Biennial or at major museums today. Not in contemporary work anyway. And the exceptions to that monopoly, which exist, further blur the ability to discriminate the autonomous. The second issue is pedagogical. If the underclass is to fully sustain the movement toward change, it must articulate itself with the tools of domination, but find ways (and some, if not many) are going to be aesthetic.

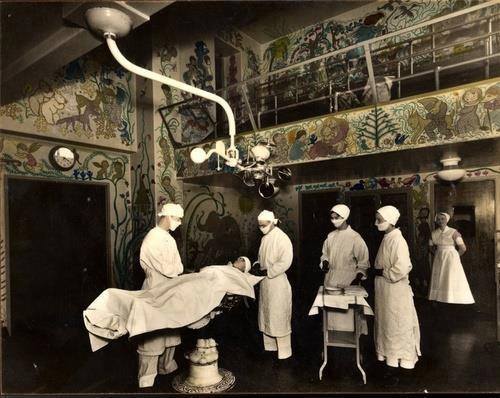

Barnes Jewish Hospital, NYC. Early 20th century.

Kato Shuichi wrote that “Japanese culture became structured with its aesthetic values at the center. Aesthetic concerns often prevailed even over religious beliefs and duties.” This the result of long isolation, Shuichi suggests, but that result was that religion (Buddhist, prior to Zen) became an art. “The art of Muromachi Japan was not influenced by Zen, rather Zen became the art.” This is from Donald Richie’s book on Japanese aesthetics. At the end of which Richie laments Japan’s too great absorption of Western values. The most pernicious Western influence was to destroy the value of solitude and simplicity. Or, of seriousness. A seriousness that aestheticizes the everday. Or rather, more precisely, the concrete materiality of the everyday. For that materiality was invested with attention.

“Well, in fact, this democratization of arts and culture is fairly recent, as ideas go. And I have never been sure that a wide audience is necessary or even desirable for art. Art is not there to foment revolution. Its purpose, as I repeat endlessly, paraphrasing Adorno, resides in its purposelessness. From the autonomy born of this recognition, one can begin to forge an emancipatory vision, and to create works of art that provide experience, stimulate dreams, and I don’t know what else. But that is important. However, it is not something the majority of people are going to have an interest in. ”

Great piece John. I would like to follow up on this point regarding audience. I agree that a wide audience is not necessary, but the nature of art audience in any current regard is problematic. Its not only accusations of elitism that hurt contemporary art, though the significant education required to appreciate so called zombie formalism is counterproductive in my opinion, its the class values that dictate and form the art produced for the small current audience. Let me explain my take, and its similar to your take later in the article. The look, material, and context of almost all art found in contemporary galleries and institutions today has been selected and dictated by those who either consume these products or those who act as court jesters informing the rulers, curators, art historians and dealers etc. For an artist to make any money or be professional you really have to toe this line and the work is fundamentally altered before its even exists. Thus the narrow audience in charge of the owning and selecting of the art has an inordinate amount of input that to my mind nullifies much meaning or potential meaning. You are left with an alternate commodity and little else. The valid or new ideas that have been explored get endlessly rehashed, a few new artists are allowed in the inner circle and everyone else, critics included laments on how terrible it all is. For the viewer out of this loop who hopes to catch a glimpse of this product is like gazing at a trophy case for a moment. One is left with some afterglow that fades rapidly as there is no real hope of living or existing with these objects.

A democracy of audience is a simplistic fix, especially with such a conditioned and subjugated population, but how about art that is conceived outside of these values? Maybe the conception of art needs to find a way to keep the work in a place of low value monetarily as an aesthetically oppositional idea, not just a theory to be taught and never practiced. You seem to allude to as much, but an alternative audience might be what is missing here, no matter the size.

@david:

Good comment. And yes, I mean the ‘crapstraction’ as one critic wrote is now so homogenized and so clearly catering to a certain audience and its needs that its mind numbing in its uniformity. The Saltz article is pretty much correct in that regard. Which is why the bonsai model appealed to me a way, as goofy as that sounds. In other words, the way out of this is by de-professionalizing it. There are a host of questions in that, framed with a marxist pov, but the Saatchis and white cube, and zwimmer and the rest of elite galleries are there to sell to very wealthy collectors. And that might include buying for Exxon even. Its hard to separate exxon from certain foundations and institutions now. Don Thompson’s books are informative on this. So….the de-professionalized artist still needs an education, and training and thats where I think its interesting to imagine more training in fine arts that reflect Valpariso’s open university for architecture. And see, even go back to The Bauhaus……..they were not there to produce artists for the Venice biennial ….they were looking to alter society. So…the real solution is destroy capitalism…but short of that, there needs to be guilds and schools and crafts organizations that are not commodity oriented. If we’re speaking painting per se. Each medium now has its own set of compromises. The performing arts are far different, really…..but just as bad. But painting has to come out of something where the goal is not to be as rich as the people buying you. I want artists to make money in this system, but i want their work to not be so utterly usurped by the hegemony of auction houses and galleries and etc. The ‘bad mural at the community center’ syndrome need not exist. Id love to see more radical form in those murals………and that leads us back to audience again. If someone like , I dont know, ….lelts say just Amy Feldman….a very sort of lightweight painter, but still facile….talented…..or Tirelli or Burri….weighter artists or Kiefer or someone…….painted the community center wall, that would be marvelous……..but the people who run those places usually dont feel much confidence in their taste, and they will want a clear message and realism and etc etc etc. So the solution is to push aesthetic education as important, and aesthetic lay education in particular.

Right, education as a long view, but so many artists are compromised by these top down values which are in turn reinforced in MFA programs. We are talking about integrity mixed with insight, sadly each is few and far between, let alone both in the same person or teacher. For an institution to have this is almost impossible. I have witnessed this very conflict of education vs illusion of career in a faculty meeting as a MFA student. It was one teacher vs everyone else, he actually won the minor battle but certainly lost the war. Art schools and MFA programs are as complicit here as you say theatre MFA programs are. For this to happen in middle or high school would require activists, coming from where I don’t know when most “educated” artists not only buy the company line but will defend it even as it marginalizes them.

My take is that a few artists need to reorient themselves to find breakthroughs that exist in under explored areas outside of institution and quick monetization but can offer something that is not currently on view. Of course there is the eating issue, but planning and hard choices will be required. I am not talking craft posing as art or your usual etsy stuff, but a real long view investigation that could be amateur in nature or an offshoot paid for by professional work. At the very least there would be an alternative provided for the public now and in history.

I just wanted to say how much I appreciate this posting. I am an artist who has no idea whatsoever how to rebel against the endless chit-chat, the rise of corporate media, the degrading of language, the (lack of) attention and marginalization of difficult work, the spiritual retreat, the snideness and polarity of reductionism and dismissal, the myth of success and rise in cynicism, or the neutralizing effects of the professionalization of art. No idea at all, other than to work quietly and seriously. Thank you for articulating all of this.