Malik Sidibe

“Of all the arguments put forward with respect to it {art}, virtually no references are made to music, literature, cinema, dance or photography. Almost all of them bear instead on an object definable as that which succeeds to the place of painting, i.e. the arrangements of objects, the photographs, the video apparatuses, the computers – and sometimes even the performances – that occupy the spaces on whose walls portraits were previously to be seen. It would be wrong, however, to criticize these arrangements for their ‘partiality’. Indeed, “art” is not the common concept that unifies the different arts. It is the ‘dispositif’ which renders them visible. And painting is not merely the name of an art. It is the name of a system of presentation of a form of art’s visiblity. Properly speaking, ‘contemporary art’ is a name for that ‘dispositif’ which has taken the same place and function. What the term ‘art’ designates in its singularity is the framing of a space of presentation by which the things of art are identified as such.”

Jacques Ranciere

I was thinking a lot this week about several questions related to the above quote. Ranciere goes on to posit two strands of, what he calls, ‘post utopian’ art, and the ways in which art impinges on, or is informed by, or itself informs the political. I was struck by several on-line dialogues I read this week, pertaining to the arts, and specifically to theatre, and also when I read the upcoming seasons for a number of major U.S. (like the Guthrie….I mean WTF?) and U.K. theatres. Almost forty years ago, now, Herbert Blau pointed out the lack of theory in U.S. theatre artists. The same today can be said of the U.K. and, really, most of Europe save perhaps Germany and France. What struck me, however, was how utterly tedious these seasons seemed, and how banal are the discussions about theatre by, mostly, theatre artists. I always wonder at why someone wants to become an artist. Today, honestly, it is more opaque than ever. And here I think again about the topic of mimesis, something Ranciere mentions in his introduction to Aesthetics and its Discontents. That mimesis is that which distinguised the artist from the artisan (or entertainer). For mimesis defined something of a special relation between a way of doing, and a way of being which is affected by this doing.

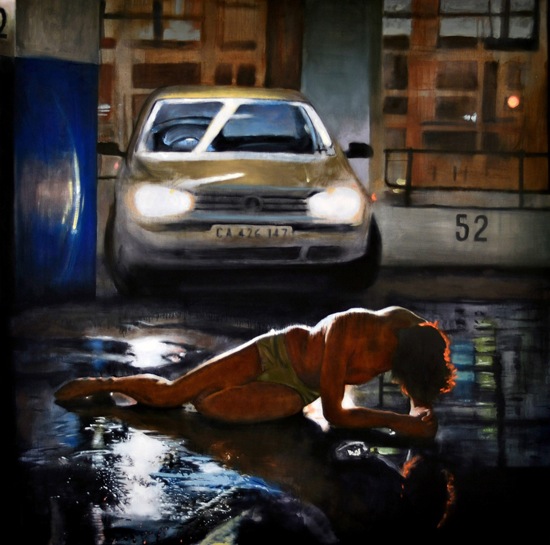

Matthew Hindley

Now, to trace the evolution, historically, of the meaning of “aesthetics” is too complex for a single post, but it is something I hope to return to in coming posts. For, the relationship between representative art and that which in “modern” art came to focus on the presence of the artist, on his materials, and on its own discipline rather than an agreed upon notion of nature. What Ranciere sees is essentially that modern neo liberalism, democratic politics, and modern (especially not representational) art have served to create a new social space. In this space a new redistribution of sensibility, or sense perception has reshaped how people share (or not) their political understanding. The divisions Ranciere posits are often confusing, but he does sort of suggest something like what Auerbach did vis a vis literature, in the first chapter of Mimesis For Auerbach it was Homer vs. the King James Bible. But to bring this to bear on the political…“Art is not…political because of the messages and sentiments it conveys concerning the state of the world. Neither is it political because of the manner in which it might choose to represent society’s structures, or social groups, their conflicts and identities.” (Ranciere). It is political because of the distance it takes from these practices and functions. Here for Ranciere, the aesthetics of the sublime suggests the encounter with the singular artwork, creates a conflict or questioning or revelation between space/time, while the ‘relational’ art is one that constructs an intentionally unreadable or undecided situation and effects the perception of the spectator, and confuses or demands an adjustment between spectator and actor/agent.

What interests me here, for the purpose of this posting, has to do with my sense of how discourse (sort of what Ranciere would include in his regime of art) about culture is forever being narrowed.

“Rancière uses the term police to refer to this compound of entities, institutions,

discourses and practices through which a metropolis‟ or a nation‟s order is produced

and procured.

What is particular to the police is that, according to Rancière, it participates in the creation, legitimization and sustainment of the premises of individualand collective experience and positions within the social corpus. In other words, the police produces, reproduces and operates the hegemonic distribution of the forms of social participation that are available to individuals and institutions within a particular society.”

Ruben Yepes

Robert Irwin

The culture industry, the corporate dominated system of image and narrative creation has not just functioned as a propaganda machine (it does that, too, certainly) but is co-opting metaphor and erasing allegory, while introducing a series of artifical paradigms for social change. As an example, much of the ecology movement feels increasingly generalized and used to manufacture intellectual lynch mobs. Topics such as climate change or Fukushima, or GM food are in each instance presented with a certain specific aesthetic style and grammar. There is a new jargon of ecological authenticity. Or the manufactured distractions provided by corporate media (Pussy Riot, gay marriage, or the ‘quenelle’) which serve as platforms for the individual reader or viewer to express a contained and safe outrage. In each case the story is sentimentalized and the asked for agreement (the lynch mob position) places the reader in an assigned role for which he or she is excessively congratulated. And this sanitizes the scapegoating mechanism and rids it of any dark aggression or rivalry. The untruth of the whole, as Adorno and Horkheimer put it, is obscured, in fact the whole is abstracted in a way, made bland, while atomized violence or injustice is enclosed within a pre-agreed criticism that cannot go beyond the, usually, cyber social media screen form of expression. The resulting dialogue is sharply proscribed and narrowed by this format. For example, to question, say, the background of scientists on all sides of the climate debate is to be met with anger. To wonder at the state department’s manipulation of foreign policy stories, which is highly effective, but their ineptitude dealing with climate stories is, again, to be met with anger. To suggest maybe Fukushima is going to be a pretext for more states of emergency — and people are furious, even though the ocean has been a dumping ground for nuclear radioactive waste for decades, is to be met with anger. The question is not if there is an environmental crisis, but rather to clearly identify the cause or causes, and the remedies, if there are any. Too often it seems people are trusting those who caused the problem. In fact most enviromental discourse is new-age cliche. It is undialectical and seems a remnant of pop psychological mysticism, carefully cleansed of anti Imperialst analysis.

The new civic role is just a branded accoutrement to the rest of daily life, which largely consists of shopping. Ranciere’s value as a thinker is in his insights on modernity: where modernity entails speaking in certain ways about certain things; so that participation demands one follow certain rules. Those rules constitute a poetics, or an aestheticized faux politics.

Zwelethu Mthethwa

Today the “police” are embedded in all consumer activity. Not only is there the NSA, tracking one’s every keystroke, but there is a more infernal shaping of personal expression. This is why there is a need to understand the various tracks or branches of aesthetic thinking. For one of the trends of the Spectacle is limit and abridge and control access to and prohibit the creation of the pre-conditions (ritual space) for processing an image, whether formally an artwork, or just an advertisment.

One of the problems I have with critics like Danto, or Lyotard, has to do with their assumptions about modern art, at least in relation to what they offer up as post modern. If their criticism relies on an idea that the ‘modern’ (and where that starts is never quite clear) was somehow childish in its Utopian belief that art could change the world. Besides being wildly reductive, its also just wrong. It is a strangely patronizing idea predicated upon a secondly reductive reading of Romanticism. There was never really (except in a few cases) the Hegelian belief that art would culminate in the great end of the historical master narrative. There was, however, a belief that art and culture, the experience of artworks demanded and even created a space for engagement that released or constructed (it depended) new awareness, both individually and collectively. The avant garde (any of them, really) were also anti conformist, and critical of state power, and of the bourgeoise. The desire for social change is, so the script goes, an unsophisticated and immature indulgence. This is really a problem, for to use the Bauhaus again, such descriptions and categories make something simple minded and naive, if not retarded, of the work of a school founded on a belief of revolutionary potential. The de-fault position of many art critics today ends up reactionary. So that in fact, what critics like Danto are doing is to write from within the new enclosure of advanced hyperreality and hyperbranding. And this is itself an intellectually denuded and infantilized consumerist, and revisionist. More, it is to write from a vantage point that is state/corporate created and with a vocabulary also vetted by institutional authority.

For Ranciere, in fact, what he describes as an aesthetic regime, cannot exist unless a disruption occurs, unless the established sensible distribution is altered. What this model allows for Ranciere is to suggest that the kitsch corporate culture industry is not art because it is so seamlessly constructed from within the prevailing sensible organization.

Charles Saatchi & Nigella Lawson, pre choke.

The aesthetics of politics or the politics of aesthetics. In the end, this is a somewhat false distinction, for usually one cannot really seperate the experience of culture in this way. Both, as Ranciere admits, spring from a common impulse, and that is the way of being of the community. And this begs a disgression here…

Jasper Johns

Warhol

Gerhard Richter

Bruce Nauman

Roy Lichtenstein

Robert Rauschenberg

Joseph Beuys

Ed Ruscha

Francis Bacon

Lucien Freud

Cy Twombly

Damien Hurst

Jeff Koons

Martin Kippenberger

Donald Judd

Willem De Kooning

Murakami

Peter Fishli, David Weiss

Richard Serra

Antoni Tapies

Maurizio Cattelan

Andreas Gursky

David Hockney

Richard Diebenkorn

Basquiatt

These are the top contemporary artists according to an informal survey conduced by Don Thompson, whose book, The 12 Million Dollar Stuffed Shark is an engaging and perceptive study of the art market. The survey particpants were mostly dealers and gallery owners, a few auction house experts, and a couple agents. The definition of ‘contemporary’ is vague, and certainly the definition of ‘important’ is even more vague. Thompson himself quotes Walter Sickert’s 1910 comment; “Have they so wrought that it will be impossible henceforth, for those who follow, ever again to act as if they had not existed”.

Rinko Kawauchi

Its not a bad place to start, that remark. I have often used it when discussing Beckett or Genet. A playwright today cannot write a play without addressing the shadows of Beckett and Genet, and probably of Pinter as well. Now Thompson also asked a few, specifically, a consultant at Christie’s auction house, and got a similar list only with Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince added, and I think a couple others. Personally I find Sherman’s inclusion absurd to the same degree I find Abramovic’s fame absurd. Now, why De Kooning is on this list and not Rothko or Pollack is unclear. I would say, take off Lichtenstein and Ruscha, take off Nauman, probably, and take off Murakami and Cattelan. I mean I sort of like Cattelan, but he feels a second or third tier sort of artist. But this is the problem with lists, which I loathe. Hell, I’d take off Kippleberger and Basquiat, too. Just off the top of my head I would think Burri belongs on here, and Helen Frankenthaler, and obviously Rothko and Pollack, Twarkov, Kline, and Newman if go back to WW2. More recently, Luc Tuymans perhaps, or Michael Borremons, or Lupitzky, or Kiefer, and there are a host of photographers I think can be thought of seriously…far more seriously than a Damien Hirst. Say Lewis Baltz and Stephen Shore, and the Wilson sisters, and Hiroshi Sugimoto, or Sammy Baloji. I mean the list Thompson created is based on the “art market”. The selling, and more, the collecting of modern art. If one thinks of South Africans David Goldblatt, or Pieter Hugo, or the Angolan photographer Depara, or a favorite of mine, Malik Sidibe, from Mali, just for openers, you suddenly realize for a variety of reasons that these artists are not marketable. Maybe after their death. Or Zwelethu Mthethwa, or the great Cameroonian photographer Sammy Fosso…none of these artists comes out of fine arts programs. All of them are significantly more serious than Jeff Koons…and I don’t even hate Koons. Or take Seydou Keita, another truly significant photographer from Africa. I could list ten Japanese photographers as worthy as Gursky, but they don’t create work for dealers or auction houses or sales agents.

Nandipha Mntambo

Technology made taking photographs quite easy, and affordable. The awareness of African photography, and as Simon Njami says; “The term Africa is a neccessary damage.. I would say that what they all have in common is that they were, for the great majority, colonized by Europe.” remains lodged within an anthropological frame, and THIS is really the role of contemporary colonialism. Andreas Gursky or Candida Hofer, two photographers I think very highly of, are also very conscious of making very large format photos, often on metal surfaces, but in other words, making them imitate paintings, making them museum-ready. And this was a point that Julian Stallabras made about that generation of photography students that came out of studying with Hilla and Bernd Becher. But to return to Berger for a moment, where he echoes Benjamin, in suggesting that technological reproduction has stolen something (an ‘aura’) from the unique work of art, I think it is clear that another current has surfaced, and nowhere is it more clear than in the various photographs from often self taught photographers (in this case I am thinking of the Africans listed above); a current in which that aura arrives via the radical vision of artists working from a place much closer to that shared community idea of the medieval mason. Perhaps it is that one is more aware of an interaction with a stranger, when looking at photographs. The stranger can be the subject of the photo, but it is also, always, the photograher him or herself. Berger has written that a context must be provided, possibly even a text, to give it a place in narrated time. I don’t disagree with this, but in a sense, the photo is an introduction, and if these images are without context, well, that has always been part of the allure of the photograph. They are dreams or memories of a stranger, even if we knew something of who the photographer was. Archival photos, for example those of Matthew Brady, haunt us because we have no narrative. We do not know these people. The mimetic action is hence very pronounced, and this feels almost primal to me. I think only in a culture in which the mimetic is so discouraged, and atrophied, do the dreams of the stranger feel threatening.

Katy Grannan

There is, however, a lingering counter emotion that is linked to the voyeuristic. If Diane Arbus always leaves one uncomfortable because of feeling manipulated, the same cannot be said for David Goldblatt or Malik Sidibe. But I think it is clear that notions of realism are raised with all photographs. Here it becomes a real question how versimilitude is to be treated. A Gregory Crewsdon, or Cindy Sherman, or Victoria Beercroft are parodies of “mystery”, are in a sense intentionally creating an ironic ‘sublime’, and reflect an era where film and TV are paradigmatic. With Crewsdon I feel much as I do with David Lynch; there is a visual sneering. The post modern tendency has been to distrust techonological determinism, but I think that’s probably too simple. I think the technology of all lens based artwork contains a tendency toward both surveillance, but also to authority. But I digress…again…

The absurdity of auction prices for contemporary art is often pointed to when discussion turns to art and it’s cultural value. The reality is that there are about forty five thousand artists in London, and another forty five thousand in New York, right now who are looking for representation, for a gallery or an agent or a dealer who will take them on. Most of them come from University programs, and most of them desire to be branded artists in the same way Damien Hirst is branded. Only a few hundred are shown, and most of those soon return to other work, other jobs, only to be replaced by a new graduating class of aspiring little Hirsts and Koonses.

Pieter Hugo

There are painters like South African Matthew Hindley, who deserve more visibility. Or Austrian Ingmar Alge, or Romanian Serban Savu, one of my personal favorites. But these days, when a Tracey Emin, or Richard Prince are selling for millions, it is pretty hard to keep a straight face. But it is equally hard for younger artists, those outside the New York/London axis to compete, and or course, in the end they don’t compete. Now part of this has to do with the evolution of the art market, the way in which agents and dealers have enclosed the means of access, and the way celebrity galleries have created a brand. Charles Saatchi, the odious London based dealer and gallery owner, is the man who made Damien Hirst. The shark story itself is amusing (first shark rotted due to lack of correct pickling) but more, it is illustrative of something going on regards conceptual art, and the new post post post pop art moment. Hirst doesn’t just do dissecated or pickled animals, he also does paintings. Well, his assistants do paintings, for like Jeff Koons, Hirst is an industrial workshop that cranks out product. His paintings are openly done by assistants (Hirst suggests the best Hirsts are done by an assistant named Rachel). What Hirst is doing, really, is to create a label that reads Damien Hirst. I mean Yves St.Laurant doesnt sew his own dresses does he?

So the community of artists one could have found in New York after WW2 doesnt really exist anymore, or Paris in the early 20th century. There are only University and Art School programs. Last month I wrote about the socialist influence and idealism that informed the creation of the Bauhaus School. I sense today a small uptick in regional movements, but these are artists who won’t ever be auctioned (at least in their lifetimes) at Sotheby’s. One has to remember also that there has been an explosion in the building of museums over the last ten or fifteen years. I would argue that this is in direct proportion to the recession in communities of artists. This growth in museums means there is a need for more product. Enter the industrial assembly lines of Koons and Hirst. And more, enter the assembly line of Art School grads. There is a strange aspect to this institutional training of artists. Nobody expects the work to be any good, firstly. Secondly, even if they did, the understanding is that it really doesnt matter much. Good, bad, who cares, and anyway, what’s the difference. I recently read a thread on a social media site in which someone criticized Kanye West for saying of himself, “Im a creative genius”. A good many comments suggested there was nothing wrong with this. It was seen as simply a form of self branding. Humility? The fuck cares about humility. Get with the program son, this is all about marketing and money. It is fitting I managed to sit through Scorcese’s new film this week; “The Wolf of Wall Street”, which is in one way, the signature movie of the age. Except it’s probably not even good enough to be an advert. Whatever happened to the Scorcese who made Goodfella’s? Now I never thought any of his films were really very good, but at least three or four of his early films still feel coherent and stand up as supportable melodrama of some sort. This one , well, I expected the narration to be handed over to Robin Leach at any moment.

Hans Op de Beek

But I want to bring this back to the discussion at the top and that quote of Ranciere. One of the things he points out is that the property of being a work of art is not given by a criteria of technical perfection, not by any virtuosity, but by being perceived, or ascribed, as or to, a specific sensory and intellectual realm, a ritual space. Now the sculptor or painter or mason of antiquity, in Egypt or Greece, or India, was not authoring an artwork, but was expressing a shared belief, or at least perceptual practice, of the society or community in which he or she lived. One of the points Ranciere makes, and in another way Adorno and Benjamin both make it, too, is the message or opinion of an artwork is not where the political implications are to be found, but in the way all artworks manage to redistribute the sensible (Ranciere) and attention and shape thought. For all ‘art’ that exists in ritual space is going to inscribe something of how to think about others, and in a sense share the individual’s experience of their own history of trauma (childhood), if not share social dreams. Theatre of course IS a form of thought. But this goes back to the very top quote which I find so interesting; that painting has been the ur-artistic form. This is true probably given what is known of Paleolithic cave drawing, and even if those cave dwellers staged “performances” (it is known they had music, and made flutes) which is likely, the paradigmatic form is the permanent image on the wall. And there is always, it seems to me, something of solitude embedded in the artwork. And maybe my distrust of certain work has to do with the failure to provide solitude in the work. For even theatre, if done with rigor, provides solitidue. It is civic as well, but this may actually be the borderline between performance art and theatre. In theatre there is a solitude, even if off stage, and in Performance Art there is none, because there is no off stage.

Ed Halter, in an interview over at Mousse Magazine, wrote:

“I think the somewhat surprising rise of Marina Abramović is telling, here, in the ways that both the art world and popular culture have changed. Her work doesn’t at first seem to be made for mass appeal; she doesn’t play with the codes of popular culture, like artists along the lines of Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst. But remember how photos of people crying at her MoMA show circulated on Tumblr and Facebook? Then there were those images of people waiting in long lines, a phenomenon which had a kind of recursive allure of its own. These close-up and candid moments have now become the currency of a new economy of images that’s very different from the spectacularity of earlier generations, which operated more along the lines of a studio-to-broadcast model. Images people took on their own phones were reblogged along with stuff from the New York Times or MoMA’s own press photos. Abramović and Lady Gaga rose to prominence around the same time, with the same logic, in that regard at least. It’s like Pop Art in reverse: Warhol took the content of mass culture and brought it into art, while they’re using “art” as content and spreading it through contemporary forms of mass media—but really they’re only producing a new form of kitsch, complete with mawkish sentimentality.”

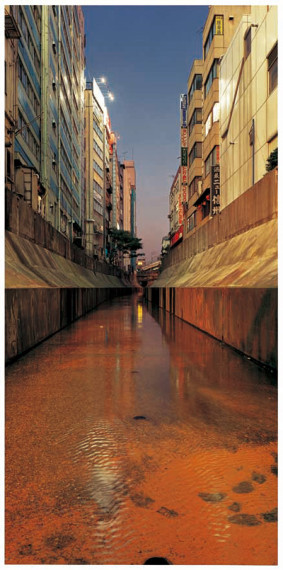

Naoya Hatakeyama

So, the politics of performance are always, with a few rare exceptions (Bob Flanagan for one) is reactionary. For it is by definition, almost, going to be negating “illusion”, and to negate illusion one must conform to what is accepted as “real”. There is the elimination of the sacred in a sense, and there cannot be an off-stage (for Flanagan the offstage was his own death). But Abramovic is the same as Hirst, that is certain, and really, it is not very different from haute couture. Fashion is always about killing thought, and erasing all but the product. The products designed by the Bauhaus, differ, in that that community is embedded, not excluded. Dolce & Gabana are not interested in solitude, nor is Abramovic or Hirst. High fashion has about it the lingering faint odor of death, of decayed meat. Partly it is the unnatural body of the model (and it is interesting that ballet in a sense shares this, but there the death is embraced as sacrifice) and the sense of transgression, which isnt really transgression at all, but only simulated transgression. The rubes buy into this (P Diddy, or Kanye or Jay Z, or Kelly Osborne, or Ryan Phillipe…a handful of athletes) and one wants to tell these people that nothing makes one appear quite so moronic as sitting front row at Fashion Week. It is interesting that when someone recently asked why I wanted to be a writer, an artist, I had to think for a moment or two, and then answered because I didn’t want to ‘have’ to work. So the transformation of untruth, of toil, or domination is the goal of all art it seems to me. Adorno would say “the social function of art is to not have one”, but that is not to say, that the “not having” part neednt contribute to a refiguring of ritual and sensible space. Is there a trickle down effect here? Well, perhaps, but the more optimistic answer is that community coalesces around the autonomy of solitude.

One of the reasons that mass culture, corporate mass kitsch, is about killing culture is that it valorizes the status quo, and that process means valorizing the banalities of daily struggle. In a sense its anti aesthetic actually negatively aestheticizes oppression. The autonomous artist refuses to (per Ranciere again) decorate the mundane world.

“Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln”, Disneyland 1965 to present.

As a final thought, relating to film and TV. I’ve noticed increasingly that a very narrow definition of logic is at work in most Hollywood film. Now, this really means the critical reaction to film is increasingly narrow. There are a dozen good English language films in the last few years (most Australian, but some British, and even a couple from the U.S.), but almost all of them were poorly reviewed. In fact so reactionary are critics that if a film get a positive review, I become suspicious. Films that I initially liked, if well recieved, I go back and re-evaluate, because the ‘official’ establishment reponse is usually so wrong. A film I liked, and have mentioned before, Texas Killing Fields, got uniformally bad reviews. One critic wondered that there was any reason to have made this film? This isn’t going to be asked of Lone Survivor or Captain Phillips, or Wolf of Wall Street. One of the mechanisms working to narrow the logic is to make clear that there is a “reason” for this film to exist. And those reasons narrow. It’s based on a true story. It’s adapted from a book and the book was an Oprah selection. Its patriotic. It’s got a “strong female character”, or gay character, or some other bromide for liberals (strong woman is usually cop or warrior or DA or something). You get the idea. There is another trend at work; the making of ‘working class stories’. These are always made by rich white kids. Its like taking a vacation to Belize or something. Its anthropological. We are studying the rare and nearly extinct blue collar union member…quiet now…they easily spook. There….there’s one….and soon, they have hired Christian Bale or Brad Pitt to play this blue collar dinosaur. There is a clear reason the film was made. Its a study of a exotic flora and fauna. There is so much wrong with how Western culture approaches art today, especially, I think, film. If you look at this season’s TV schedule, you can find a half dozen (at least) new cop shows. Each one an utter fantasy. Each one more dishonest and fascistic than the next. This is basic network stuff. The prestige cable sources will deliever smarter material, and usually in fact, HBO and Showtime provide at least less obvious sorts of cliches. Often in fact they exhibit a good deal more skill in how they deliever the same message.

Fashion Week, NYC, 2012

I have nothing against pulp. But increasingly the critical response to stuff is in the hands of deeply ignorant people. Consumer advocates, as I’ve said before. The effect is that the menu for 2014 on network and cable TV increasingly resembles something developed in the mind of Leni Riefenstahl. Increasingly, and I didn’t know this was possible, human life is even MORE disposible, and violence MORE embraced. Increasingly, the white supremacist trope excludes almost all other pov.

The racism of even the educated left, let alone the liberals, is staggering. It’s on display in all this “entertainment”. Jaw dropping. And when Dieudonne, the Arab/French commedian, starts hanging with various fascists, or anti semites, though also with a host of other strange people, athletes, etc, he is crucified. The problem is, he is crucified for being Arab, not for hanging with fascists. Others have said more objectionable and openly racist remarks (Zizek for one, but half of the leaders of Israel, not to mention the open contempt and racism of a Michael Bloomberg). Nobody has hung with more fascists than the Queen of England. But well, thats treated with a fair degree of “relativity”. I was amazed at the “outrage” of leftists (well, ok, college attending white leftists) at Dieudonne and the criticism Diana Johnstone absorbed over her article on this topic. And it reminds again of the luxury of outrage. Oh dear oh dear oh dear, hanging out with holocaust deniers. I mean for fuck sake, did anyone get killed? Did anyone get beat up? Did anyone fire bomb someone’s house? Rape? Mutilate? No. Mostly, it was about anti semitic jokes. And this gesture which gained a lot of traction through the banlieus. Well, Im sorry, but Im come down on the side of the banlieu everytime (well, not Fontenay-aux-Rose or Clamart, but the Clichy-sous-Bois). On principle. The violence against Muslims and Arabs has been acute, the marginalization and poverty has been extreme. These are the ‘racaille’ Sarkozy railed against. When communities are robbed of hope, they often turn to the politics of resentment. They also do what they have to. And yet again, we can introduce the scapegoating mechanism. Maybe Girard is more right than I think, even. The real point is that when Zizek makes jokes about race, he is joking from the position of a privileged white class (and nobody please tell me how Balkan marginal he is, please) about Roma, or Africans, or Asians. When Dieudonne makes anti semitic jokes, it is the voice of the racaille. That’s the difference. And that difference is significant. The question though is whether it is more significant to attack a comedien for his bigoted jokes, and fall in line with the reactionary right and liberal class consensus of opprobrium, or to defend the comedian, because of his class and culture, and to then oppose the right wing, white, liberals who crucify him. Anti semitism is one expression of the fascist sensibility, but what we are talking about here are jokes, and a comedian from a marginalized class who has been, in one sense, hounded into positions of self defense, but which are, yes, bigoted.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/10562264/France-wins-battle-to-ban-anti-Semitic-comedian.html

If the hypocricy of the above article is not obvious, then I am stumped where to begin in explaining it. If a white French comedian had made jokes about Arabs, obviously nothing would be done. The Israeli government almost daily issues racist slurs against Muslims. In the US Fox news has made anti Muslim rhetoric a staple of their programming, with a healthy second helping of anti Latino racism. Remember that FOX employs Oliver North. Sit back, take a second, and ponder anew the implications of that fact.

Clichy Sous Bois, (Paris).

A final note on art economics. It is a fact that when the Dutch government, in the 80s, subsidized Dutch artists by purchasing their work, that later, when that subsidy program ended, those artists works were resold to the public. They fetched about one fifth the price the government paid. What is the moral here? The moral to my mind is that while I wish for a socialist system where people have their rent paid and health care paid, the role of the artist is oppositional and that opposition cannot be done in comfort, finally. This is not to say there are not, obviously, dozens of now wealthy artists who produce exceptional visionary work. The problem is that economics in a system of mass inequality will create a deeply asymmetrical artistic regime, as Ranciere has it. Artistic value is imprinted on economic value, and vice versa.

Remember when Mary Boone initiated the practice of selling work that hadn’t yet been painted (of Schnabel and Fischl)? This is the assembly line for museums. Every museum needs around a thousand works, and probably more. And museums are now the arbiters of taste, really, more than auctions or galleries, and certainly more than critics. But they all work with each other to manufacture prestige, interest, and value. Billionaires donate or lend from their private collections, or galleries sell at discount to museums. All this interdependence is about money. It is about almost nothing else. Citigroup and Deutsche Bank have created departments to advise rich clients on art investment (usually old Masters, but some modern). They then handle, for a fee, the loan outs to museums. Insurance is bought to cover the transport, and on it goes. This is creating a lot of capital. Meanwhile the rich client of Citigroup has generated a good deal of press for himself or herself, and the priceless aura of exclusivity.

Olu Oguibe

A final coda on the topic of collective guilt. Often one feels a fatigue, a despair even, at the failure of so many in the West to make the effort to learn about the lies of government, and to educate themselves about history. Of course, it needs remembering that the majority of people, the vast majority of people today live under duress and in fear. They havent the time to do more than try to survive, to feed their families, and to stay out of prison. The crimes are the crimes of the propriator class, the owners of media, the Pentagon and death merchants of the defense industry. Those are the criminals. There is no complicity really, but there is a sense, I think, of collective madness. And that madness, the result of a constant buffering and battering by consumerist media, of a background made up of the noises of violence and suffering, tends to effect everyone. Nobody is immune from mass culture, from screen addictions, from poisoned food and the acelerated shaming and snitching set in motion by the educated classes. Let alone the effects of mass surveillance. The colonizing of the imagination has left a population unable to express intimacy, or to find the space for reflection, and for empathy. But the madness of many metastasizes, and even the sane must breath of the collective madness. There is so much mystification, and a society deeply invested in their kitsch definitions of sanity, of adjustment, and the trust that science and medicine can provide cures, pharmacological mostly. And just the mass cruelty to animals is proof of spiritual sickness. The indifference to the industrial level sadism against our fellow creatures is proof of some mass pathology. One must turn away from an awful lot to sustain the illusion. The psychic toxins of mass culture, of marketing and the deforming of desire, has resulted in mass derangement. Proof of the madness is, again, in the infantile vocabulary of enviromentalists. The removal of political discourse from a commodified branded form of faux resistance. And evidence of the truth of this is to be found in the police raids on serious sustainable communities. Buy a Prius, shop for expensive “organic” food, half of which is GM anyway, and buy free trade coffee for twice the price of normal coffee….thats all fine. Just don’t move off the grid and start your own farm, milk your own goats or cows, and grow your own vegetables…because then a SWAT team will arive in a new half million dollar 37,000lb ‘military grade mine removal vehicle’ to take you away. That is where we are. And to survive, it seems that such community organizing must take place. But to take place, there must be a will for it to take place, and a critique that includes identifying the enemy.. I’m not sure there is such a will.

Richard Misrach

I enjoyed reading this one, and with respect to the issues that currently plague the art world and “high culture”, I feel the ‘intelligentsia’ is just as much to blame as the bourgeois establishment, and it probably goes back to the ideas you mentioned were expressed by Lyotard. I think many of the ideas proposed by post modern philosophers were subsequently co-opted by aspiring artists who interpreted it as them being absolved of a responsibility to demonstrate “skill” or also to create work that was mimetic. As for the bourgeoisie embracing such work, well they’ll pretty much embrace any work of visual art, but not necessarily cinema or literature, that the intelligentsia says is important, since a physical work of art carries monetary value a physical copy of a novel or a celluloid reel doesn’t quite hold. If an intellectual deems said work important, then such an object becomes a status symbol in an off itself. This is hardly a recent phenomenon. Art has always been a status symbol for the upper classes. There’s certainly the issue of post-1980 neoliberalism, which I would say is tangentially related to the rut the “art world” finds itself in, although yes, it is directly related to the overall cultural rut we find ourselves in, but that’s too complex an issue to elaborate on in a single thread post.

As for current film critics being reactionary, yes that’s most likely true, but to dismiss a film because it received rave views almost seems needlessly contrarian, at least to me. That’s not to say bad films don’t become critical darlings. They certainly do and often, but I’m personally willing to take each film as it comes. But there are still a few critics worth reading. If Jonathan Rosenbaum isn’t a film critic worth someone’s time, then who is? Richard Brody and Andrew O’Hehir are also okay, as well, but not geniuses.

I think “high culture” had a much wider reach back in the 60s and 70s than it does today largely because the “intelligentsia” had a more focused and centralized agenda they could more effectively deliver to the people, whereas part of the postmodern agenda is that there is no agenda, so you have all these niche communities whether reveling in nothing more than their own idiosyncratic tastes. Now I don’t know how you personally feel about filmmakers like Bela Tarr or Pedro Costa, but I personally feel filmmakers like them would have had a wider audience fifty years ago. Now, of course, I’m sure there’s a neoliberal explanation as to why such figures have an extremely limited audience in today’s world.

hi remy, nice to see you again. I agree regards the sixties and seventies. There was simply, on one level, a better educated, or aesthetically educated audience.

here is a little architectural footnote

http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2014/jan/14/moma-loses-face/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=January+14+2014&utm_content=January+14+2014+CID_0991eadabd8de430a36bfbbdb42de0a9&utm_source=Email%20marketing%20software&utm_term=MoMA%20Loses%20Face

Could you list the Japanese photographers that you found interesting. I was introduced to Hiroshi Sugimoto through this blog and have become a fan.

Sure. Sugimoto is just so great, though. But….shomei tomatsu, Daido moriyama, Shoji Ueda…who I like a lot, and Ken Doman of the older generation. Ikko narahara is very interesting I think, and Miyako Ishiuchi. Bishin Jumonji is more commercial I guess, but still very good. Seiji Kurata does strange almost narrative photography. They are usually single person studies, but in curious circumstances I guess you could say. Yutaka Takanashi is an older guy, very good. tadahiko hayashi is a documentary photographer, who I like. Id say most japanese work in B&W. That’s a whole discussion probably.

and the two i posted above in the post. And…one other very interesting guy is Issei Suda. Also Yoshihiro Tatsuki. But Suda is sort of special I think. And Hiroh Kikai, who does odd portrait work.

I should mention another guy i quite like, who is really more Thai/Vietnamese…but I believe studied in Japan, and that is Matsato Seto. He works in color, and is really terrific.

thanks for the intro to Naoya Hatakeyama. agree w/ the post above that there are some great art intros on this blog.

on a related note, your art posts are in general just very good and really seem to nail something. you might want to consider writing a book if you haven’t already.