Ivan Albright

“The same summer I was on Lewis, a new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary was published. A sharp-eyed reader noticed that there had been a culling of words concerning nature. Under pressure, Oxford University Press revealed a list of the entries it no longer felt to be relevant to a modern-day childhood. The deletions included acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell, buttercup, catkin, conker, cowslip, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, mistletoe, nectar, newt, otter, pasture and willow. The words taking their places in the new edition included attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, bullet-point, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player and voice-mail. As I had been entranced by the language preserved in the prose‑poem of the “Peat Glossary”, so I was dismayed by the language that had fallen (been pushed) from the dictionary. For blackberry, read Blackberry.”

Robert Macfarlane

“…the judgement of taste does not reside in the positive characterization or knowledge of an object.”

Ruth Ronen

There is something strange and disquieting that takes place in season three of House of Cards, for Netflix. The first two seasons of this very well received prestige drama were enjoyable enough guilty pleasure viewing. Based on a UK series of the same name (created by Andrew Davies) the U.S. version was lushly produced, and well photographed, and Frank Underwood was a pretty enjoyable villain. It was a sort of schadenfreude experience, a predatory amoral back room political hack finding his way, almost in spite of himself, to the vice Presidency, and then, at the end of season two, to the Presidency. David Fincher was the creative force behind things, even if Beau Willimon was show’s creator (worth noting that Willimon, a Columbia and Julliard grad, was also an intern for Charles Shurmer, and worked later for both Hillary Clinton and Bill Bradley). It was slick and the supporting cast was mostly quite good. But then Season Three happened. Now I bring this up because it is representative of the way even marginally decent drama will be corrupted. Season three firstly becomes a very different sort of show. It is different in intention, in execution, and certainly in meaning. The writers forgot (?) that the Frank Underwood character (now President) was a murderer and sociopath. Apparently by virtue of becoming President, Underwood grows a conscience. Or, is it just the reflexive impetus to parrot U.S. political propaganda?

Simone Niegweg, photography.

Every bourgeois conceit that one can think of is trotted out. Every shallow bromide about American exceptionalism is restated, and every liberal concern is focused on, to the exclusion of all that made the show rather enjoyable. The need to create a cartoon version of Putin (including the cringe inducing appearance by Pussy Riot) seemed too much to resist. This was a show pandering to the perceived tastes of its target demographic. Couple this to a general lack of actual plot, and to suffocating tedium of having to watch increasing screen minutes devoted to Robin Wright’s one wooden expression, and the result was the poster child for American culture; a relentless presentation of ruling class concerns. One episode, focusing on a gay rights activist in jail in Moscow was perhaps the zenith of tone deafness. From the perspective of a country that leads the world, by a large margin, in torture and incarceration, in military war crimes and domestic repression, it was rather stunning to see the sociopathic Underwood and his now ever more noble wife, looking to defend the rights of those horribly oppressed by the evil Empire (the USSR…er…..Russia). Suddenly the audience is transported to Aaron Sorkin-land. This is imperial propaganda, and also, in a sense equally important, it is sentimental melodrama. But the codes in play remain *edgy*, and adult. It’s simply The West Wing with added nudity. There are only caricatures of class, and race issues. The foregrounding is American political legitimacy.

Kevin Cooley, photography.

There are also wholesale revisionist asides concerning U.S. history (North Korean aggression for example as the cause of the Korean war). But most disturbing perhaps was the way in which the totality amounted to a strange simulacra of drama. Of story. For really, there was no story. Looking back, there wasn’t all that much story in the first two seasons, but least a genuine cynicism distracted from this. There is also in Spacey something oddly reminiscent of Bryan Cranston in Breaking Bad. By this I mean a sort of acting that constantly reminds the audience of the actor. It is smug and self conscious and shallow. But then there is just the wholesale banality. The utter and mind numbing banality, the triteness and cliche, the blandness and lack of basic storytelling coherency. This is what I want to get at here. The quote at the very top is from an article at The Guardian. It’s worth reading here:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/27/robert-macfarlane-word-hoard-rewilding-landscape?CMP=share_btn_fb

Fransesc Burgos

One of the byproducts of technology has been the loss of verbal descriptions. Images replace them, but more and more often it’s with shallow generalized images. The individual no longer has to describe, to employ language. One can technologically reproduce or characterize via scientific (or usually a sort of ersatz science) means, by computer graphs or algorithms. Nature is distanced. Nature is, in a sense, reified. It is made user friendly by a reductive model put in place, or it is simply disappeared. The language of commerce has replaced poetics of description. The only remaining description is one intentionally pared down to emotionless dry technical classificatory measurements. Poetics is no longer associated with precision. To know a word such as shreep is, to say the least, unusual. But those words one doesn’t know, are often looked up, but just as often they are not. I never looked up every word I wasn’t sure about. Still, those sounds, the context, is planted in the brain somewhere. Its like the first time one reads say, Hegel or Kant, or Husserl or whoever. I started Hegel when I was seventeen and thought ‘what the fuck’? I persisted for a while but gave up because I figured after 100 pages that I couldn’t remember any of what I had read. Then, a year or so later it popped into my head. Reading something else. And I realized, ah, it did have meaning. In some remote tangential way, it marinated there in my brain and now auto accessed. This is how I believe learning works. One has to become as immersed as possible in subjects, and also in reading. But very few people read after college anymore. The age of books is over, sadly. I had the wisdom to never attend school after high school.

Leo Stoezel

“Mostly I just kill time,” he said, “and it dies hard.”

“There was a sad fellow over on a bar stool talking to the bartender, who was polishing a glass and listening with that plastic smile people wear when they are trying not to scream.”

“She looked playful and eager, but not quite sure of herself, like a new kitten in a house where they don’t care much about kittens.”

These quotes (first two from The Long Goodbye, and the last one from Lady in the Lake) are quintessential Chandler. In thirty some episodes of House of Cards there is nothing remotely close, that I can remember. There is only the generic blandness of Hollywood hacks. A greater actor than Spacey might know that, might find a way to suggest Underwood’s impoverished verbal gifts, but not here. In fact the bland cliches are uttered as if they were bits of Chandler level wit and poetry. Now, I don’t want to particularly pick on House of Cards, because I can’t think of a TV show that ever approached Chandler. But if one looks at American culture today, it would be difficult to find that vivid sense of writing anywhere. It isn’t what comes out of MFA programs, certainly, nor does it come from Hollywood. There are writers, of course, (though ever fewer in English it seems); Bolano, or McCarthy, whose writing is rich, and poetic. Sebald, Handke, and probably a couple others over the last thirty five years. But the suffocating repetitive blandness is what has begun to unravel the spools of memory in our brains. Honestly, these ersatz third generation dupes of real writing, real acting, real image, have accumulated and accrued to stop up the paths of collective thought. Couple to that the profoundly childish and fascistic politics of this 99% of popular culture, and no wonder the audience processes in a less attentive manner than before.

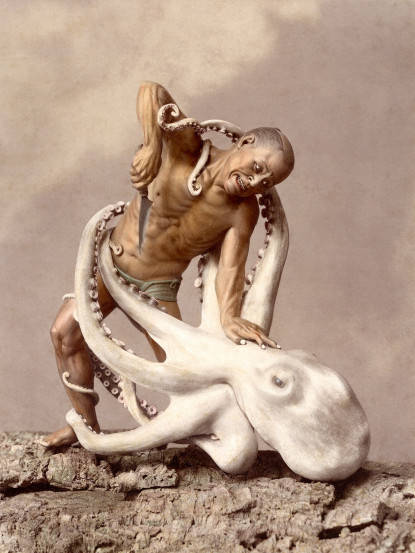

Edo Period pottery, Japan. 1700s apprx.

Marc Swanson

“The first atonal works are depositions, in the sense of psychoanalytical dream depositions.”

Adorno

A crucial aspect of Adorno’s thoughts on the ugly have to do with the false-ugly, which reflects social and political barbarism, and the revolutionary and liberating form of ugly which must not cede to an enshrining of unmediated primitivism. But primitive is a loaded and dubious term. And care must be taken when using it as an aspect of the ugly. Here one needs to see that 19th century aesthetics in Europe privileged a bourgeois notion of European progress and an Orientalist notion of *primitive* African and Asian cult beliefs about totems and religious icons. This is related to the idea of pleasure again, for once one grasps that all art is, in a sense, a cultic practice, then the question of pleasure and beauty can be more easily set aside.

Now the primitive has another meaning which is linked to the return of the repressed. This is partly the argument in Dialectic of Enlightenment. That the subsumption of myth was incomplete and ushered in or created space for the rise of fascism in the form of National Socialism. But let me leap ahead a tiny bit here, for the ugly must be more closely articulated. Too often in contemporary culture the ugly is a celebration of the cruel and barbaric. Of totalitarian logic. Art as opposition to a society of domination includes the ugly not as contra-beauty, but has a formal question. Violent and sadistic TV shows are aestheticizing the violence of society, because of the naturalistic form (even if not at all realistic, the audience has been trained to recognize the codes). This is an eroticized violence, and one that through its form is reconciling societal cruelty with itself. The ugly precedes the beautiful. “The affinity of all beauty with death has its nexus in the idea of pure form that art imposes on the diversity of the living and that is extinguished in it.” In a sense, what Adorno is saying is that the beautiful was historically compromised, that it was false reconciliation with the prevailing society of unfreedom. One cannot, however, simply recreate the archaic, for the archaic has been absorbed, and hence the futile emptiness of all *new primitivism*. The ugly, or archaic, must revive in terms of form, and in that return is found the discussion of pleasure and anxiety.

Christopher Rimmer, photography.

Nobody knows why early man painted on cave walls. But I personally doubt it was because of religion. It may well have been a learning exercise, a cooking blueprint, or teaching aid for hunting. Either way, it was of course also magical on some level for the world had not yet been disenchanted.

The sense of rationalizing away that Dionysian energy that found no contradiction in the magical and unseen with daily life, was the legacy of the Enlightenment. But there is always a process of synthesizing that reconciles earlier aspects of aesthetic practice. The point here though, for Adorno beauty signified a broken promise. In modernist art the expression of the ugly was an echo of the incomplete rationalizing and as said above, it had both regressive and progressive aspects. On the one hand it signaled an embrace of bondage and oppression, and on the other it signaled the opposite. The ugly is a resistance to the false reconciliation of contemporary society. The issue of anxiety then, and pleasure, have to be seen in this light.

Robin Wright; “House of Cards” 2013 Netflix.

Now all art is partaking of those trace elements of the archaic. The ugly is that deeper layer of refusal that had been rationalized by ideas of the beautiful. And in beauty comes anxiety for as Ruth Ronen puts it “In beauty, losing sight of desire elicits anxiety in the observer.” Lacan saw beauty as partly desire and partly agony. This is really not very different than Adorno. I have never understood Kant’s idea of moral feeling and beauty, but in any case it’s regressive. Beauty I think triggers a recognition of that promise which has been broken, and hence the desire felt when looking at the object is not quite the same desire one feels in narration. That is an entire other posting, but this beauty and its containing of desire, produces a particular quality and kind of memory. This is reverie and Bachelard wrote a lot on the subject. He wrote “I am a dreamer of words, of written words. I think I am reading…”.

Bishin Jumonji, photography.

I think that if one accepts the basic outline of Freudian and Lacanian theory regarding the infant, then that early sense of lack drives on the acquisition of language. Of grammar. Of writing eventually. From there the story of the world begins. In the beginning was the word. And contained within that story is both anxiety, and forgetfulness and by extension homesickness. This is all part of the originary script for our consciousness. And so we must dream. Why would the noble savage dream if not because he forgot something? All of this is to say that beauty, and the relation of that concept to society is mediated deeply by the creation of an abstract pleasure. Real pleasure is erotic and sensual. The aesthetic pleasure is tinged with melancholy, which is why entertainment is so fraudulent an idea. Pure pleasure….as in partying and orgies and amusement parks and recreation, all of this is closer to failed tragedy. It is the tragic of the bureaucratic soul. The conceptual beauty is a beauty of disappointment. And it’s hard not to agree with Lacan, too, when he suggests the connection of this conceptual beauty with death. If the primal story formed in our originary psyche is one of lack, of rivalry, and of anxiety — a desire to keep our secret hidden, then the beautiful is the limit of the tragic (per Lacan). The idea of catharsis, and identification, all of that is just the shudder we feel when force ourselves to think of death. And beauty, at least the beautiful object, is most beautiful when it returns our gaze. But today…and maybe I am finally reaching what I wanted to talk about …the deforming impulse in mass commodified culture is one that has absorbed such ideas, and regurgitated them; or like cultural cud, constantly chewed and mashed and redigested and then the returned to be chewed again. An Intellectual/aesthetic ruminant society. The compulsive anxiety driven repetition of the same story, the same camera, the same scenes, all this is cud. But it is not quite that easy or simple. House of Cards, Season 3, serves an example of something more.

Shiva, Chola dynasty, 12th century AD, South India.

Beauty marks the limit of desire, said Lacan. Here one has to separate out a couple different registers of beauty, or of the experience of beauty. Sexual desire may relate to beauty, but often does not. In fact, it often is in closer relationship with the ugly or ambivalent. The individual only identifies beauty from a catalogue of learned associations. The first among which is likely Nature. But the experience of pleasure is not quite directly linked to beauty. This is where contemporary mass culture has altered notions of pleasure. One must consume what one identifies as pleasurable, or, it is only pleasurable by virtue of consuming it. Contemporary mass culture is neither autonomous nor does it care much about beauty or desire. These are narratives to be consumed, and they pander to and flatter their target audience. Part of what happened at the end of modernism, if one can say it this way, was that art became conceptual, distanced from the experience of the artwork, and ideas of revulsion or disgust were introduced as objects of aesthetic consideration. This is all a bit beside the point here, for the point is that commodities were encroaching on aesthetic experience. The commodity preceded the artwork. The psychoanalytic aspect had shifted the focus to the conditions of the audience/subject. Here is it worth a short few thoughts on audience. I wrote before on Adorno’s sense, over sixty years ago, of there no longer being an audience for difficult or demanding artwork. This is obviously even more true today. But I fear it erodes the psychic mechanisms of even those remaining few who do look to art and culture for some sense of Utopian imagination and mimesis. For the sense of I get is that the relentless presentation of the fake has taken a toll on everyone. The anxiety of society collectively is also contributing to this sense of imaginative torpor. Anxiety has no object, but its about something (which paraphrases Freud). I think many people are afraid, too. The most vulnerable are increasingly afraid. The more privileged, relatively, are anxious. Anxiety produces inhibitions, a general slowing down of activity. But it also, as Lacan noted, produces an inverse desire. The desire not to have a desire. In today’s culture there is a desire not to imagine. In a sense anxiety disguises relationships by inhibition. There is a growing sense of fear though fear of a specific kind, a specific psychological use; the fear of anxiety, for occluded behind anxiety is our shriveling desire. We are a society now reaching a saturation of lack, of absence in dreams and imagination; we desire escape from anxiety, certainly, but know only how to further inhibit. The I-desire-distraction, for in distraction comes the ability to compulsively repeat, and compulsively avoid. That primordial mimetic engagement is deflected, again, and then again.

And so, the narcissistic child can retain a sense of emotional primacy, by simply retaining itself as the center of attention. Narratives that produce this shallow identification must be repeated over and over at accelerating rates of transfer. Ruth Ronen wrote that Lacan saw the camouflaged cause of desire serving to block out anxiety. The desire for creativity, acts of creativity and imagination are deflected to the desire to consume, creative shopping etc, and so such *shopping* (or whatever) serves to, short term, block out anxiety. For finally, the subject today is gripped with profound levels of anxiety. People dare not dream, unless the dream is sanctioned. Surveillance wears at the psyche, as well. Do not step outside the boundaries of acceptable behavior, literally. Look at airport security; that space of optimal securitization of person. Strip, submit to xray, to various magnetic fields, and all the time you are watched, and your belongings examined. We live, in one way, in a permanent state of airport passenger stress.

Gus Heinze

Now, a number of writers have taken to theorizing about *theatre* (in the broad sense) and violence. Brad Evans wrote that “theatre is often deployed to describe all manner of events from sporting occasions to forms of protest that display something of the carnevalesque. But how very real deployments of brutal force are framed by consciously appropriating theatrical discourse.” Evans is correct, although I want to look at, again, this notion of violence in relation to beauty and pleasure and anxiety. Theatre, and I’d include film and TV here, in this context (though they are indeed quite different in other contexts) is making ideas of pleasure and beauty obsolete. For the beginning of any narrative marks the raising of a curtain. And as Blau said, even theatres without curtains remember that a curtain was once there. At that moment, with any artwork…from an HBO series to an amateur community theatre production, the audience has signed on for and anticipates a process of dreamwork, of mimesis — that re-telling of something that is both our own story, always, and a story of the *other* always. And in each case History, collectively, is activated as well. There is a great problem in discussions of violence and morality, in artworks, in culture, because this fact is so often ignored. Everyone, it seems, has grown so used to the idea of manipulation and propaganda, that the more fundamental and essential experience of all art is forgotten. Adorno wrote that because of their distance from any purpose, artworks resemble the “superfluous vagrant who will not completely acquiesce to fixed property and settled civilization.”

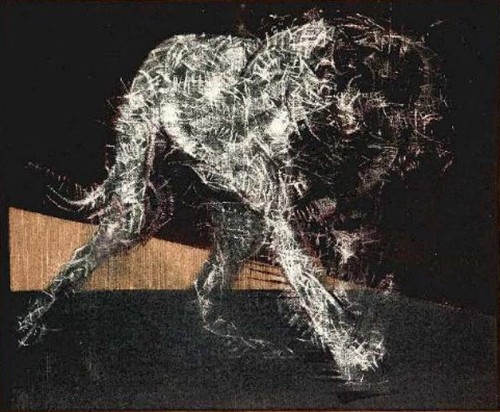

Francis Bacon:

“When talking about the violence of paint, it’s nothing to do with the violence of war. It’s to do with an attempt to remake the violence of reality…We nearly always live through screens—a screened existence. And I sometimes think, when people say my work looks violent, that I have been able to clear away one or two of the veils or screens.”

And this is such a marvelous quote, and speaks to this question of qualities of violence. Representations, in fiction, of violence is part of why humans tell each other stories, why we paint, even compose music. There is, in fact, a great dignity is ceremonies of mourning, of re-enacting the violence. The horror of WW1, as Treverso rightly saw, was that it marked the first war in which rationality had caught up and overtaken the violent impulse to strike out or back. This was industrial death, planned, and efficient. That rationality has continued to develop. From Los Alamos to HAARP, to the new militarized police on main street. Art is not complicit. The artist is not the enemy or the creator of violence. That would be the ruling class bankers and CEOs, the generals and politicians and wealthy elite. When I start to hear that artists are complicit, I worry. But let me return to that Adorno quote above on the superfluous vagrant.

This is an elusive idea, but it is germane to considerations of propaganda and celebrations of domination and cruelty. I asked at the top what society expects from culture and art today. The very question demands more from critique than simply another form of coercion. More than just moral indignation, for the endgame of such logic is join up with the Roundheads and Cromwell. Adorno also said that in all artworks something appears that does not exist. And this takes one back to early man drawing on those cave walls. Artworks encipher and fuse elements that ‘do’ exist, but in service to the inescapable truth of our inner lives. The failure to see the extent of ruling class fear is a failure to include the encipherment of artistic expression, and mimesis. The rich have more to lose, and yet they feel exempted from the various interpretations of mass culture. Pleasure today is the aftertaste of manipulation, and it is only the reflexive guilt born of that preartistic anxiety, and of a realization of art’s antisocial or anticultural character. When those archaic traces have finally been erased, then culture has, as Adorno said, capitulated.

Gertrude Abercrombie

This is the horror of mass culture today. It is the horror of House of Cards, created by a 36 year old former Clinton flunkie and go-fer. The culture has capitulated. The audience cannot distinguish qualities of pleasure or beauty because it cannot even grasp fully its own anxiety in the face of narrative. The sheer duplicity of Season three, the Pussy Riot appearance, the Russophobic cartoon characters, the sentimentalized astro turf dialogue about injustice; all of it is served up for purposes of flattery and validation. A validation for a system in which war criminals and blood soaked ghouls are held up for applause. In which nobody notices that a sociopath has become President because in fact, that is almost the only kind of person who really does become president.

The critique of violence as intolerable is complex, and it raises an issue that Adorno himself raised repeatedly; the truth content of art.

“By its form alone art promises what is not…” Adorno.

Francis Bacon. painting of a dog, 1952.

That desire in the face of beauty, coupled to the boundary marked by the same experience, is still (per Adorno again) the longing for the fulfillment of what was promised. Art cannot be reduced to theoretical analysis, not completely. In a society of pure exchange value art represents that which cannot be exchanged, is unsubsumable. The language of art, even in a visual vocabulary, cannot only be that which cannot be exchanged. Art is a foreshadowing of radical praxis, but itself is only a dream of it. But dreams die when they succumb to the reality principle. Violence is done in far more insidious ways than representations of violence. They are done in centering narrative in white male ruling class worlds for which the poor are only visitors, or unwanted poachers. How hard would it have been to ridicule the State Department creation of Pussy Riot? To suggest U.S. foreign policy is Imperialist and trailing blood and body parts behind it? How hard? Why are writers so easily bought off? Is the money really the reason to betray what you know and believe? How much does it cost the participant in this orgy of disinformation when allegory is removed, when only the suffering of the rich matters? There is a real history, one that most everyone knows at least a little about, so how does it go so totally missing? The dream is not a real dream because of form, said Adorno. And in the form, and poetics resides something untranslatable. The opinions don’t matter if the form were truthful. But everything in Season three is counterfeit. It is a TV show about celebrity, and about the rightness of social domination. Murder is alright if you are white and a *winner*. Collateral damage. The violence to be concerned about is not the image of a knife going into a throat, it is in the smug expression of celebrity actors, in the snarky treatment of cartoon Russians, and in the familiar repetitive and predictable camera and editing. We know what comes next. Everything is there to tell us what comes next. Anxiety permeates the subject-viewer, for such ‘entertainments’ create anxiety. If *I* depend on the gaze of the Other, of knowing who I am because of something I missed, an appointment, a forgotten fleeting memory — then make sure there is no room for the uncanny, for the correctness you hear in those Chandler similes, or in the language of archaic Nature. Double down on banality. Jump through the hoops. Curry favor with the wealthy. What artist signs on to work for Hillary Clinton? That is not the consciousness of opposition. Nor of revolution. Deny the richness of difficult work, accuse it of elitism. The left has to take culture seriously, though. The endless emphasis on themes and applause for bad theatre or film because of the overt politics is really a reactionary position in the end. For it is falling under the same bus that runs over the entirety of society. The streetcar named anxiety, the streetcar of disenchantment.

Kozaburo Tamamura, photography.

Still, there are aesthetically other problems at work. Adorno is criticized as out of date, and in the sense of method, that seems true (I don’t believe it is) but its most certainly not theoretically. One has to realize that the post modern or post structuralist program has dismissed the idea of understanding art. That part Jameson got right. That Adorno by virtue of being outdated, was actually far more critically insightful than all of the Badiou, Foucault, and god forbid Zizeks out there. It is worth considering that the calls for Adorno as out of date usually focus on the dismissing of critical resistance through artworks. Aesthetic resistance which demands that the contemporary educated class give up their favorite TV shows, is just not going to be popular. Hohendahl quote Adorno, in his excellent analysis apropos of fandom:

“The injustice committed by all cheerful art, especially by entertainment, is probably an injustice to the dead; to accumulated speechless pain.”

Academia today is a career driven enterprise. I can’t teach, for example, nor do I get invitations to various conferences. None of the many very smart and politically aware people I know, friends, are invited either. The endless blather about pedagogy, which sometimes I lose patience with, never addresses the naked exclusionary practices of the University. The academic world probably needs to address this in the same way the writers for shows such as House of Cards need to address their own prostitution. In the post modern era though, an easy excuse has already been provided.

“The academic world probably needs to address this in the same way the writers for shows such as House of Cards need to address their own prostitution. In the post modern era though, an easy excuse has already been provided.”

http://truth-out.org/news/item/29396-higher-education-and-the-promise-of-insurgent-public-memory

Great post. The article you mentioned, about the loss of nature words, fills me with a kind of sadness — it’s like the loss of Eden, of that first naming of all things…

Apropos:

A Light exists in Spring

Not present on the Year

At any other period —

When March is scarcely here

A Color stands abroad

On Solitary Fields

That Science cannot overtake

But Human Nature feels.

It waits upon the Lawn,

It shows the furthest Tree

Upon the furthest Slope you know

It almost speaks to you.

Then as Horizons step

Or Noons report away

Without the Formula of sound

It passes and we stay —

A quality of loss

Affecting our Content

As Trade had suddenly encroached

Upon a Sacrament.

— Emily Dickinson

And indeed, Trade has encroached upon our Sacrament. And is here to stay, perhaps…

Here …something from The Academy of Television Arts and Sciences….you might find it of interest, John….

http://www.emmys.com//news/features/master-house

You invoke modernism’s end in conceptualism as being “art that distances itself from the experience of the artwork.” But if you are bringing up the idea of experiencing artwork, you are calling into question subjectivity–unavoidably and logically. Who is experiencing?

And Modernism–coming along as it did at a time when people were much more tied to tradition, an obstacle for capital and consumerism– was essentially about redefinition, “progress”, and the rejection of the old modalities of rationalism…but also embracing the technological and even fetishing the New. Conceptual art was actually the last gasp of artists who wished to escape from commodified objects of art for sale and to create a space where there was not a-thing-that-commanded-a-price, but a consideration of that thing, that price, and that command: examining the encroachment of commodity upon aesthetic experience. By the (brief) time Conceptual Art became the dominant discourse, commodity and artwork had long become an ouroboros…destined to reassert itself with a vengeance.

The ideas of revulsion and disgust (which, I personally feel, got the short shrift) were of course introduced along with ideas of beauty and taste as subjects of an analysis that had a very strong political and even psychic critique at heart, along with the re-reading of psychoanalysis through Lacan, Deleuze/Guattari, Derrida & the post-structuralists…the opposite of “distancing from the experience of the artwork” indeed, getting closer to its core. I dont understand why “shifting the focus to the conditions of the audience/subject” is a “bad” thing. Why not shift the focus? The danger it seems to me is not in any particular shift of focus by the artist or philosopher working on sorting all this out, but in the ahistorical, purposeful mindlessness of unexamined mass popular culture as a juggernaut…as you are essentially arguing in all your posts.

Well……..thanks Exir. Thanks for those links joanna….horrifying. And Rita……..this is a large topic that is hard to do justice to in this format…..but:

Conceptual artists have ended up as rich as any other brand of art. And just as commodified. And we might argue your definitions of modernism (I would…but its not the issue here, and I wouldnt disagree enough anyway)….but I think you have to distinguish between beauty as an idea, and that particular period when revulsion, say, or disgust were given their moment, and thats something I want to write about more, because it touches on theatre directly. Anyway, this starts to feel semantic a little bit, because *beauty* was a guiding principle and a big topic for 18th and 19th century European aesthetics and philosophy. So when I write about beauty, it is really in relation to Kant. And i had wanted to talk more about the sublime, but sort of ran out of space this time. As for distancing…….look, I know the Conceptual artists (capital C) believed what you say, but i simply dont buy it. But here the discussion becomes about HOW that experience takes place, and about, primarily , *mimesis*. And at best, the high priests of Conceptual Art were not mimetic, except as a secondary activity. Now you can argue that that is perfectly fine and doesnt constitute distancing. For me the lack of space, or the absence of that aperture or opening for mimesis means the engagement prioritizes the intellectual — and I can anticipate the argument against this, but Id probably suggest that the debate then takes a twofold form; one its about defining mimesis, and two, its about what constitutes experience. And maybe there is a third tier which is related to the *object*. And that becomes pretty complicated because how does one talk about the object in narrative? But narrative was not part of conceptual art, except by the viewer….and that in turn, I believe, reinforces my position. Trust me I get all the arguments FOR Conceptual art….i just think, and this has been my position from the start, that they fail to understand an element of the sensuous as well , more importantly, by disregarding the mimetic. And when that happens, it feels as if it fits all too seamlessly into the post modern retreat from the material world (which was a part of this particular post). I mean it happened in english poetry at the turn of the 20th century where the individual, the human subject position became primary and tended, increasingly, to disregard nature and history. (as opposed to say the Spanish poets).

I dont know if Conceptual Art can be allegorical, for example/ Maybe thats not seen as a problem, or as compensated for by other factors. Maybe. But I believe if one looks at the effects of post modernism, and post structuralism, whatever you want to call it, it would be hard not to see it depolitizing and dematerializing rather than the opposite, no matter the intention. I mentioned at the end the attacks on Adorno. And this is very much to the point. (there is a book, The Sovereignty of Art by Menke….on Derrida and Adorno, which is pretty good actually)> I happen to believe strongly that Aesthetic Theory is the greatest book ever written on art. I dont think its even close in fact. And i think, increasingly that if you read Adorno’s late lectures….from the mid 60s, on history and freedom, another on sociology I believe, and one on music…..that you see how prescient he was, how he had seen what was coming. He was old by then, but they are beautiful lectures…..compassionate and they belie his reputation as this grumpy old fuck who called the cops on the student protesters (something he was, i guess, in the end wrong about…but he had reasons). Anyway……..i have no problem shifting the focus per se. I have a problem though with the way it has happened, and the material conditions that encouraged the shift.

@Rita “And Modernism–coming along as it did at a time when people were much more tied to tradition, an obstacle for capital and consumerism– was essentially about redefinition, “progress”, and the rejection of the old modalities of rationalism…but also embracing the technological and even fetishing the New.”

I think that is an oversimplification, perhaps a great one. What you say might be true with regards to the Futurists, but many modernists were precisely the opposite. Take T. S. Eliot, for example — “These fragments I have shored against my ruins”, that doesn’t sound very much like glorifying progress, does it? And what about Yeats’ entire oeuvre? These people were looking backwards, trying to preserve what little they can of the tradition, in whatever form they will (Yeats stubbornly clung to traditional forms and meters, Eliot grudgingly yielded to the fragmentation of his age, but with an extreme bad taste in his mouth). And if you read Eliot in “Four Quartets”, or his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent”, you can see that he saw the poet’s task very much as saying the same thing all poets have said before, but in a different way.

If one reads this, and links to the *artists* involved and the organization, tell me if there is a single *artist* without academic accreditation.

http://hyperallergic.com/186876/teachable-moments-from-a-conference-on-art-and-education/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=What+Just+Happened+The+Bjrk+Experience+at+MoMA&utm_content=What+Just+Happened+The+Bjrk+Experience+at+MoMA+CID_900e8d10ad6ca1e0f733eaccc5ce7a9b&utm_source=HyperallergicNewsletter&utm_term=Teachable%20Moments%20from%20a%20Conference%20on%20Art%20and%20Education

The answer is no by the way.

@exir and rita:

Yeah, this is the danger in discussions of modernism. There were several modernisms. But mostly I think Exir is the more right in this case. For modernism was doing both things…(ah, dialectics !), and adorno points this out. The avant garde was certainly fetishizing the new, under the aegis of *progress*, but there were many currents in which (and Benjamin was part of this thinking) the recouping of the past was a part of the resistance to mass conformity and mass man. I mentioned in the post the *new primitivists*….that was a nostalgia for the past, not recouping or incorporating it in some way. The modernists like Pound and Eliot, and those painters of the 20s were very different in theme and also ideologically different from those in the 50s. From Eliot to the Beats, and Roethke and James Wright ….from Matisse to Pollock. There is an arc in there if one examines it from the pov of traditions and utopian planning or dreaming. LeCorbusier for example, expressed both socialist tendencies….and fascist ones ( http://www.failedarchitecture.com/le-corbusiers-visions-for-fascist-addis-ababa/).

I’d never seen House of Cards before last week, so I went back and looked at a little from season 1. It’s startling what an apology, a fascistic show it is, I thought right from the start. The British show is about Thatcherism – the cynicism and sociopathy of the politicians and their class agenda are one. They are out to crush the working class and get richer and richer. All this is turned inside out in the American show. The antiHero has no class agenda and no quest for profit. It’s not clear why he wants to be a politician. For “power” perhaps which seems to mean nothing concretely, as empty as a rpg victory. The American politican system is portrayed as pure and perfect, [rotecting “moderation” and chugging along untouched by the filth of the thrillingly amoral protagonist with his outmoded accent of suthin powah. There is no imperialism. There is no CIA. there is no genocide and plunder. The portrayal of the media is laughable. There is a benevolent process of domestic rule and the ruthlessness of the protagonist is portrayed a sunleashed only in his largely inexplicable quest to attain the honor of performing as a glorified clerk of a disembodied System that is always in the background and infallibly virtuous. There is no class praxis.

The politics of this Jacobean court intrigue is even a level down from the renaissance plays that it mimics because there isnt’ even a metaphoric level contending with actual capitalist imperial politics — the intrigues doesn’t even embody anything. If anything there is a subtle effect of making imperial politics seem like just a domestic and bourgeois social mishigas. Like so many other shows, the world portrayed is standing in for the cuthroat world of Hollywood and television — in the West Wing, the white house is an idealist movie studio or tv network, in this Washington is the Hollywood of Entourage and The Player.

But without the $$$ of either washington or hollywood

I think disappearing the money is the whole idea really. This supposedly cynical, gritty, jaundiced, unsentimentalized view of Washington discovers no money, no profit, no plunder, no empire but as benevolent world police.

SO it must not be there.

idealist=idealised

It is worth comparing to the UK show. What I felt in the first season was this blandness, but the arch villain was cynical and it allowed for this obscuring of the fact that there wasn’t really much of a story. That’s why i said that Underwood, almost in spite of himself, becomes VP. You never got the idea he had some Machiavellian plan. He just sort of stumbled into these situations and then cynically sought power. But he had no grand plan and wasnt motivated by a grand plan or any political beliefs. But just having him be amoral allowed the story, what there was of it, to move forward. Yes its aaron sorkin land. Its exactly that. But in season three, the writing becomes utterly confused even on its own terms. Its as if they couldnt even sustain this shallow cyncism.

What does he want to do with this new power? Who knows. Its as i said, by virtue of taking office he acquires some new moral vision. I dont know. But this is a show created by a guy who interned for Shurmer, and worked with hillary clinton. Then took a playwrighting course with anti castro Cuban ed machado at Columbia (i know machado, who is sort of my son’s titular grandfather…….its complicated……..). All Hollywood shows are reflections of the studio. There are only the interests of this privileged ownership class. Thats the full extent of it. You’re quite right there is no real world against which this story is set. There are no occupying armies, no trade deals, no defense contractors or great chessboard. There is only the banality of an insular fantasy world made up of the daily concerns of Brentwood and Beverly Hills. And on top of this, season three is presented as if everyone forgot Underwood was a sociopathic murderer. Its just childish, the level of the whole vision is like a children;s book.

Isn’;t it curious that this transformation of the view of the politician as sociopathic iago can be instantly altered simply by bringing Putin onstage./ Its like the transformation of Bush that happened when OBL or Sadam Hussein are introduced in conversation. It;’s like how Screw Magagzine becomes feminist liberation the instant you lay a picture of Taliban next to it. That episode with pussy riot was like a heuristic demonstration of Orientalism in culture production for a class to examine.

it had a lot of zizekian alibis too

As an addendum……..the lack of perspective on court intrigues…..from the start.,…is also the way literature…..Shakespeare say….is taught. The context, history, is removed. Everything a character desires is just floating out in this abstract world of the text.

Whatever was enjoyable in the first season, a small enjoyment, was based on the premise, I think, that there was going to be a ‘reveal’ at some point. That Underwood was murdering and betraying people in order to achieve something …….which we hadnt yet been told…..but in fact there was nothing. And because its not a real world, it doesn’t matter. And this is show that won tons of awards, too.

Zizekian manoeuvres are everywhere now, the floating pov, the reversals and disavowals, the mimicry and sheer cynicism of culture product

The alibis in HoC…notice Foreign Affairs thought the fake Putin was too attractve. That’s the main alibi – he’s a thug sure but a sexy one.

(They are childish so don’t notice how childish his character is depicted as)

RasPutin gets to deliver his talking turkey speech in the basement about what the US empire really wants, but it is sort of standard Great Game board game moves, like Risk.

But it was also all delivered as if it were just filler, just rutabegarutabega bg, a formality, a ceremonial Realpolitik speech

And the way it dealth with Pussy Riot was zizekian

the two men, the antihero turned hero and RasPutin agree they are childish

their childishness in the view of these men is supposed to underscore their innocence, idealism, sincerity – exactly what they are not.

the Putin character is genuinely gracious to them, and this is an alibi and a sheild for the politics (see the show is so leeeberal and daring it s soft of RasPutin!)

and then the show’s “daring critique” of the American President is that he ends of using Pussy Riot cyncically and pretending he is sincere

and that’s the whole zizekian game

for his own cynical reason,s the antihero President ends up promoting the most sincere and brave resistance to tyranny

His very cynicism is the armored tank that virtuous naivety rides to battle in

His lie is a higher truth

He says Pussy Riot are brave as a lie from the podium, but it is a truth.

And this Straussian theme of the Noble Lie was introduced earlier, its very conscious, at the dinner, in a very Zizekian way, wheels within wheels

The first lady says her husband quote Pushkin once at a dinner, saying “A deception that elevates us is more dear than a hundred low truths.”

Then RasPutin says “your husband didn’t really say that”

and she admits “no he didn’t”

that’s supposed to be the joke…her deception is better than the truht.

but the truth is Pushkin didn’t say that; its erroneously attributed to him on the web in some places because a reactionary critic wrote that sentence in some celebrated essay about Pushkin and (the Cossack rebel leader) Pugachev, who turns up as a character in The Captain’s Daughter (there was a great russian or polish film adaptation of this in the 90s or early 00s) as well as being the subject of Pushkin’s history of the Cossack Rebellion….and the essay is about how different Pugachev appears in the history (he’s a savage merciless sadist) and in the novella (he’s capriciously kindly)

Thats its chief messaging I think– sure the US is cynicism incarnate (no hope of making the US empire seems altrustic and virtuous in intention anymore) but it is backing virtuous causes. Sure US empire wants to invade and divide Syria for the wrong reasons but its the right thing and the rebels are brave and so sincere and virtuous they seem childish.

Yes! This is stuff I am sure Billimon picked up from the political class he worked for. Its actually sort of filtered Ayn Rand, by way of Leo Strauss and samantha power. I mean that’s the idea, the lie is really a higher truth if WE tell it. The world is what we say it is.

The Putin character, played by a danish actor, is seen as childish. While Underwood we know is a realist….even if a sociopath…….and so he is given the moral high ground. In all these shows…Homeland, Scandal, 24, spooks….all of them, feature the inherent superiority of clean cut white men. The elite cadre of boy scouts, with sunday school manners and square jaws. its extraordinarily regressive. These anal sadistic boy scouts who RESPECT AUTHORITY, say yessir and yes mame………these are the morally righteous. And they also represent a slightly different version of the chris kyle template. But they all eschew sex, drugs, and all wear suits and ties usually. It is a particular white male fantasy circa 2015. All of them are emotionally withdrawn, too. So, frank underwood contains echos of this. He went to The Citadel, was a white southerner from a military school, and ….so again……never mind he’s a sociopath. He embodies a higher truth.

Its fascinating to graph the signifiers, in a sense. The lone black man is essentially castrated. He returns home to live with his mother or something. He cant take the heat in the great Underwood kitchen. The double lie in the story, such as it is, is that Underwood is the villain, except he’s not. He’s also the (see above) the kind of man for a tough job. That tough job is putting the childish orientalist thug in his place. I mean we could go on about the off hand comments made……….russia as corrupt, america as NOT corrupt, america has a free press, unlike those other places….Roosha……and then the senile Supreme Court justice…….never never never are SCJ shown to be venal autocratic opporutnists. They are always de facto GREAT men. The great man theme surfaces in all these shows. From west wing to Homeland to 24. My god, that last season of 24 was a stunning example of that. (yes I watch everything). The great white man. Honestly, it is not far from Ramar of the Jungle.

all manner of critique coming in………but this while wrong …well, in many respects, is also rather interesting and has some insights. http://www.nationofchange.org/2015/03/04/real-life-frank-underwoods-netflix-house-of-cards-and-third-way/

The Americans — i just peeked at this, the first couple episodes — is the same thing in ta different permutation. It’;s also the Third Way (as in Nazism imagined as the option that’s neither lib democracy nor communism) American society is seen as menaced and flawed by a degeneration — vicious poor people, shallowness of the mainstream, anomie. The show pictures communism as a horrid nazi terror society, but it admires the self sacrifice and commitment of the wife spy. The American society and waty of life is obviously superior, that’s not in question, but the commie wife has a commitmnt and a selfless devotion to her country and a moral rectitutde of sorts that is admired and must be adopted to save American society. Capitalism is great, America is great — its democracy that is the danger because the people are decadent. The commies have a ruthlessness and a purpose we are to admire even as they are clearly devoted to the wrong object of faith. The message is utterly fascist.

All these shows share this conception of the problem – Capitalism is great, but the society is decadent, and democracy makes it decadent. Competition is healthy but selflness, devotion to the volk is needed to secure the society against the tendency of individualism and democracy toward chaos and degeneration. The System, the structure of propery and power, is pure and basically divine. It is permnanent and good. But people are vile. Those that serve the System will do good despite themselves and those who dont need to be exterminated like vermin

*thanks joanna*

http://www.thestranger.com/theater/features/2015/03/04/21821025/bought-and-paid-forandmdashis-acts-seven-ways-to-get-there-the-new-model-for-arts-patronage

Its so Zizekian…and it works. look at the comment:

http://www.nationofchange.org/2015/03/04/real-life-frank-underwoods-netflix-house-of-cards-and-third-way/#comment-1887359323

“Except Frank Underwood is the villain. So who cares what comes out of his mouth? We’re rooting against him, not for him.”

Yeah, The Americans is however considerably better written. The main model though is capitalism is superior and that is why capitalism won out. There is a certain poignancy to certain parts in The Americans. I remember when I lived in Poland, especially out of the cities (I was in Kielce for 8 months teaching at one point) where older people would discuss their longing, during communism, for this american fantasy. Most now wanted communism back, but they said at the time they had this sense of how they didnt dress as cool, didnt drink Pepsi cola, etc. And The Americans captures some of that …..maybe its just me though. Also, the two leads are simply VASTLY better actors than spacey and wright. They manage to disguise a lot of the flaws. The show was created by an CIA agent. Oddly. Or not. But in general, there is that model in play, and its very deeply ingrained, and its ingrained and embedded in ways I think most audiences dont even notice. At all. The show also, I think, while privileging capital, does critique a reagan era mind set in the West. The central american operative, an american, modeled I guess on a sort of ollie north type…..is fascistic and so at least you have those mediations, plus the fact that the protagonists, husband and wife, are in fact Russian. And the girl elena is russian. And she’s a sort of tragic protagonist. Its odd, because in a way The Americans, even ideologically, offends me far less. Form again. The fact that odd moments rise to another level, allows to feel less anger. But of course House of Cards is wildly popular. Better budgeted, and is a more pure expression of the ownership class today. Perhaps paradoxically the CIA writer is more genuinely cynical, hence less offensive than the hillary clinton staffer, whose cynicism is directed at the poor./

I guess it should be noted that the wife in The Americans, the Russian agent,….her great love is a black radical— late in season one as i recall. She is forced to sort of give him up because it blows her cover. That in fact is a pretty unusual relationship ….and that’s what i mean. Give me the CIA guy over the Juliard/Clinton hack.

In season 3 episode on press conference, press sec announces “a bilateral approach [with russia] to mideast peace. As you know the Palestinians have refused to negotiate until Israeli troops leave the Jordan Valley”

i think the producers and distributors of The Americans definitely see the idea that the black radical is the tool of a spy of a fascistic communist empire as the kind of propaganda they want to disseminate, and the fact that one feels for the Russian wife is the alibi for that view. but yeah it is oddly more ambivalent, not about the USSR, but about this couple, who are the heros, so one roots for them, but they abuse (simple, stereotypes) black people horrifically (poison son to twist arm of maid whose emplopyer is actually very nice woman who cares about her maid and maids family) from the start. Its kind of backfiring I guess with audiences disposed to root for the commies and just to set the portrayal of communism as Nazism aside; it is so hokey and so sort of seperate from the drama of the couple that its easy to do, when watching, but of course that portrayal of communism as nazism speaks to most of the imperial core audience for that show

it is though as you say not surprising that the CIA guy can see the Soviet spies as people of conviction and complexity while the liberal ideologues create their comic book evil clowns

The thing I find interesting, and I really do, is that the ambivalence is linked to the form in a sense. I mean The Ameriicans is deceptively well made, its far less predictable for example. And the communists…even the playboy at embassy, are very likable and sort of complex. The background is cartoon though. The Russian state is depicted in cartoon strokes. But I find myself interested in the two leads, because i am drawn in by that ambivalence. The form, by which i mean acting, and pace and the elliptical quality of the story…at least at times….makes for at least a discussion about it. House of Cards is insulting. It so valorizes wealth and privilege.

and yes, *the jordan valley*……….best use the word Palestine as little as possible.

would be interesting to discuss the UK mini series The Honorable Woman. Great cast….the guy who made it really is highly skilled. But its hugely ambivalent exercise in Israeli and Palestinian narratives.

Would be an interesting exercise: what percentage of TV show producers are nowadays former spies/State Dept agents/political aides? And is it a higher percentage than before? Because nowadays whenever I hear about a new drama, invariably I read you mention a link to some sort of established political dynasty. As if we needed more proof of the military-industrial-entertainment complex……..

Hi John. I think cheerful art gets a bad rap. It’s all context. I’ve been watching ’70s shows lately, All in the Family and The Jeffersons, and Chico and the Man. As well as a nostalgic stroll through better times when blacks and Chicanos were making their way out of the ghettos, I’m calmed by observing how we once made fun of bigots (black and white!), and the ruling class (Monty Python’s Upper Class Twits sketch. Now of course we idolize them! For the Brits, I thought Upstairs Downstairs had a mildly socialist bent. It’s modern version Downton Abby, seems to be giving us commoners butler lessons. Extraordinary!

…particularly The Jeffersons. George is about as bigoted as Archie Bunker, yet they seem to get along in a funny, bridling kind of way. Doubt you’d find that kind of subtle characterization on television today. It’s almost Shakespearean in range, like Othello. And George’s neighbours! The mixed race couple? In one episode, he explains to Louise why they never fight, “…because if they did, he’d end up calling her a nigger and she’d call him a honkey!” I doubt that would play in Peoria these days…

*Not sure if serious or joking…* o.0

But, wow.

Here is another article, John….http://artanddebt.org/school-debt-bohemia-on-the-disciplining-of-artists/