Desiree Dolron

“It is the lack of the experience of the imagery of real art, partly substituted and parodied by by the ready-made stereotypes of the amusement industry, which is at least one of the formative elements of the cynicism that has finally transformed the Germans, Beethoven’s own people, into Hitler’s own people.”

Adorno

“(the knocking makes us aware) that the reaction has commenced, the human has made its reflex upon the fiendish; the pulses of life are beginning to beat again; and the re-establishment of the goings-on of the world in which we live makes us profoundly sensible of the awful parenthesis that had suspended them.”

Thomas DeQuincey

‘On the Knocking of the Gate in Macbeth’.

It is too easy, and I’m guilty of this, too, to simply lump ALL TV and film (U.S. studio film anyway) into one generalized basket. When the topic of violence comes up, it is easy to say, and it’s true, that popular culture is saturated with depictions of violence. The volume, the sheer staggering numbers of guns being fired and bodies blowing apart, has by itself an importance that cannot be overestimated. But…but Shakespeare was violent, too. So was Sophocles and so was a good deal of classical literature. Beowulf, Homer, the Old Testament, and Milton. So, one cannot just dismiss material because it is violent. There is violence and then there is violence…so to speak. Or rather, in narratives, film, and TV (these days, that’s really what we’re talking about) there are varieties and qualities of violence. So its important not to confuse Crime and Punishment with Saw.

The tragic impulse contains within its Dionysian energy a form of violence. I suspect, however much one subscribes to Lacanian psychoanlysis, or even Freudian, that there is something about our psychic formation that includes rivalry and aggression. To reproduce those tensions, and the outlines of our amnesiac childhood trauma, is a basic originary impulse for all creation. The durability of crime fiction and film is connected to our own guilt, our primal mimetic sense of alienation. To deny the shadow side of ourselves is a greater harm than perhaps any, if we are speaking of the possibility for real transformation, for raised consciousness. The power of great meditations upon violence and murder, like Macbeth, or Crime and Punishment, focus on the terrible interim before the act, before the irreversible. Or upon the guilt that follows such an act. There is at bottom a deep respect for life that drives these stories of violence and murder. So one definition of what is wrong in contemporary writing, and film and TV, is the trivializing of the value of life, the tearing down of the idea of life’s dignity. The greatest harm though, I believe, is the sentimental kitsch that stands in for actual human emotion. For it eradicates the human. It is a violence to form and soul. It is the basic lie of storytelling. But I will get to that. First, I think there is an intersection here with the entire way in which “reality” is manufactured by media and the state, and by corporate cultural entities. A film such as Capt. America, the one with a pretentious subtitle, is a cartoon. I am not sure the wholesale violence in such junk is the primary problem. The ideological backdrop is far more disturbing, and the jingoism. Now, does this cartoon patriotism serve and form part of the ideological and intellectual fabric of the enthusiastic audience that consumes it? Probably to some degree, certainly. But I suspect there is a larger audience of educated white kids (mostly male) who see this with a jaundiced cynical eye, and these are the media savy well schooled cultural dilettantes of the post modern U.S. Now, the violence is pretty much a given part of the structure of DC and Marvell comix. All of them reactionary in the extreme, but Im not sure these savy cynical consumers arent themselves aware of this. They just don’t care. Consciously anyway.

Guido Reni, 1610 (David and Goliath)

Then we have the violence porn of films like “Saw”. This is just degraded material on all levels, and one wonders at who makes this stuff? It is linked to the malformed sexuality of patriarchal white America, and it serves as (take your pick) an outlet for would be rapists, or training material for would-be rapists. But it is wildly misogynist and almost always, as an added bonus, politically reactionary. For in all this material, the status quo is reinforced. Then you have the ‘disposible populace’ cop franchises. This is the Bochco and Milch realm, and Dick Wolff and all of it is strikingly authoritarian. This was that turn that began with Dragnet in the 50s, where film noir became Jack Webb — the protagonists were not Knights Errant any longer, but clerks of the state, the jack boot anal retentive Webb served to usher in the era of “exploring the inner lives of the police”. From Chandler and Hammett and Cain to Law & Order and Hill Street Blues. These are the franchises in which certain models are put in place; black inner cities are criminal wastelands full of hoody wearing gangbangers, or Latino drug dealers, or even Vietnamese human traffickers. This is the world view of White men, it swings between mock liberal and trenchent open racist fascism. From “24” to the new Chicago PD, another Wolff project, that squarely hits at all the same buttons that he’s hit for twenty years. White masculinity projects. There has been such a staggering number of these shows that the audience is now watching as if watching an enshrined myth being played out. There are no surprises, only the reassuring replay of the same racist reactionary tropes they already know. And these shows depict a lot of violence. Usally “bad guys” (often poor, black and latino) do bad things and “good guys” (cops) do good things. The violence is often graphic, but not always. But then we arrive at the new prestige violence. Hannibal, and Game of Thrones. In each, there are curious elements at work. But in both, in different ways, violence is the subject.

Sophy Rickett

It is important I think to examine why, say, a film such as the 1969 Jean Pierre Melville masterpiece, Army of Shadows, differs from Game of Thrones. The violence in the Melville, especially the killing of an informer, is disturbing and the implications have deep political resonance. In Gary Oldman’s 1997 Nil by Mouth, the violence is seen in light of the social conditions that produced it, the texture of abuse diminishes everyone it touches, and it is suffered through generations vis a vis the criminal justice system, down to individual domestic battery and the general hopelessness of an entire oppressed class (Oldman was essentially making a film about his family).

But lets take the curious case of Hannibal this season. Yet another spin off from the Thomas Harris series of novels. Now, this is perhaps the prime example of elevated kistch one could find. It is beautifully shot, remarkably shot, really, and has a number of very good actors. It is vaguely literate in the sense that cliches are avoided , and familiar formula explanations are excised in favor of all things baroque; and this is all good. But what interests me here is the nature of prestige products today, and their evolution. Hannibal is visually stunning, smart, savy, and I admit a decent sort of guilty pleasure. The audience is not meant to be horrified. A few people might go “ew…..yuck”, or “gross”, but nothing in this show will ever haunt anyone’s dreams. Why? For all the sort of middle mind erudition on display, it is still just treading water, reconfiguring what Thomas Harris did decades ago with Red Dragon. As pulp novels go, that was pretty good. However, it also wasnt really about much. So in fact we have the new Bryan Fuller Hannibal, doing Red Dragon over and over and over and over, (with the intention of going for 7 seasons) and in the service of what exactly? Im not asking for a moral justification, but that would do fine; I’m more looking for the reasons that drive the success of this show, the aesthetic choices are …doing what? Well, perhaps I need to amend that earlier comment about avoiding cliches. This is a show constructed on certain recognizable associations. The audience knows these characters. Anthony Hopkins, Jody Foster, yeah yeah, are now Mads Mikelsen, and Hugh Dancey in effect, we know, we know. Hannibal Lecter, sure, we get it. And the entire depiction of psychoanalysis is worth a moment’s reflection. Evil lurks within the analysts office. The intellectuals are evil, or insane, or autistic, or idiot savants of some kind. The vulnerable or different are dangerous. The show is an indictment of intelligence.

Vera Lutter

It is the aestheticizing of violence and sadism, yes. Now, that by itself, even if that were all it was, I could even defend up to a point. The problem is, that nothing occurs in an historical vacuum. This is a show whose currency is familiarity. It is shot as it were a Rolex commerical, or a Porsche commercial. The camera is forever caressing the material, usually shot in a palette void of primary colors. But it also frames things in a very sophisticated way. First off, the show is endlessly stressing a shallow focus. So extreme that one can see lips in focus but nose hairs out of focus. Couple this to the restrictive framing, and the effect is striking. The color correction is extreme, too. Now I admit I waffle at times about this show. Because in a sense the camera is interrogating the viewer. You see high resolution items at the expense of other things. And yet, the editing is wonderfully slow. The score dissonant, and overall this world starts to take on the quality of a dream. The primary actors are very good (well, Hugh Dancey is less good, but ok) and so there is something ceremonial in a sense, or the simulcra of ceremony. Still, if the discussion is violence, then one might defend this show long before defending Dick Wolff. Once aesthetic choices are employed, there are harder questions to ask. Hannibal, for all Ive already said, is a far cry and a universe away from Capt. America, the Pretentious Soldier. Or, more, a good distance from Boardwalk Empire’s second season, in which the violence was so pervasive and so constant that it became unnerving to watch. That was just prestige violence porn. Lavish art direction in the service of junk. And of sadism. Hannibal, while lurid, and while self consciously solemn, is also pretty tongue in cheek. And it is that subtle wink to the informed viewer/consumer that places it not that far from Harold Ramis, in a sense. There is a lot of blank-stare humor, mixed with the artificial gravitis, that once, The Sopranos lived off. This is an intentionally over-serious presentation, which means of course, its not serious at all.

I think my point is that art and aesthetics are complex matters and they exist in real time. One the one hand, corporate produced cultural product is 99% reactionary, and 99% kitsch and is almost always reproducing the familiar, and all of it in service of reproduciung ruling class values. But there is stuff, worth examining, because it, in different ways, reveals a good deal about the society we live in, and more, about the mediated sub conscious of the American psyche. Or at least a good chunk of it. And there are contradictions, and one of them is to see the ever (seemingly) increasing white tours of the underclass. From Out of the Furnace, to Bad Company, to The Place Beyond the Pines, to Killing Me Softly, you have youngish white directors, from privileged backrounds, touring the “authenticity” of the underclass. Usually with white male movie stars in the lead.

Alfred Menzel

These white tours of the lumpen masses end up aestheticizing poverty, and making the degradations of daily life for the working poor a sort of aesthetic petri dish. The poor, who they basically detest, are still envied. So the appropriation of their stories is like stealing the last thing they have. The point is not the suffering for such directors, but to see what is’cool’ and marketable, what image might emerge from the experiment that can be reproduced as a commodity. The poor are not the subject, only their style.

Tom McKinley

The violence of Capt. America is a cartoon. It is propaganda. The violence of “24”, (back this season…again) is the perhaps the most pernicious expression of the collective lack of compassion in the society. It is violence as spiritual regeneration (to paraphrase Richard Slotkin), violence as cleansing, as morally uplifting, and as sexy. The majority of studio and network film and TV presents violence as entertainment. Not just the story, in which violence may occur, but the actual violence itself is presented as pleasurable. In Hannibal it is literally served to you, as a fine meal is served, and the cannibalism is part of the joke, as is the overwrought presentation. But in the Kiefer Sutherland/Jack Bauer franchise, there is no joke. This is the humorless world of the angry white man. And it tries very hard, as do other shows of this genre, to make violence attractive. This takes several forms; the coolness of weapons, the coolness of killers, the coolness of body parts exploding or of punctures or slices or chokings (this is akin to 12 year old boys stomping on a frog and marveling at the gushing entrails). Or, there is the entertainment that is meant to proceed from revenge motives. This overlaps, I suppose, with keeping society safe from whatever, terrorism, seriel killers, etc. We are meant to view their death in a way not dissimilar from Puritans watching fellow citizens in the stocks. Or public hangings. It is curious, really, that the U.S. doesnt televise executions. One would think, seriously, that such a thing falls perfectly within the value system that also manufactures stuff like Zero Dark Thirty. So, look at violence in films such as Army of Shadows, or recently, in A Prophet. These are political and metaphysical acts of violence, and in each case there are profound repurcussions.

Army of Shadows, 1969. Dr. Jean Pierre Melville

It is also, all of it, creating and reinforcing a climate of fear. Who are you to fear? Not the police, not the CIA or NSA, no, you are meant to fear the psychotic cannibals that lurk on every corner, live in almost every rural cabin or farm, and especially, are housed in prisons and asylums.

Melanie Manchot

When I wrote of the war on imagination (Henry Giroux’s term) I think the new prestige TV product is a pretty good indicator for what is going on. There is a populace now living primarely in a screen world, and in that screen world, an artifical world, there must be constant reminders of its legitimacy. And there is no better reminder than to actually, literally, use an extant film as a jumping off point. And this familiarity is pegged to shopping expertise, and this turn is pegged to irony and sarcasm.

Its curious that David Foster Wallace wrote about this twenty years ago, albeit from within a white male world view. Still, he was pretty much correct. Matt Ashbi wrote about the Wallace essay recently:

“Today’s painters understand the challenging work of the early postmodernists only as a hip aesthetic. They cannibalize the past only to spit up mad-cow renderings of “art for no sake,” “art for any sake,” “art for my sake” and “art for money.” So much art makes fun of sincerity, merely referring to rebellion without being rebellious. The paintings of Sarah Morris, Sue Williams, Dan Colen, Fiona Rae, Barry McGee and Richard Phillips fit all too comfortably inside an Urban Outfitters. Their paintings disguise banality with fashionable postmodern aesthetic and irony.

Likewise in contemporary fiction, Tao Lin has made a reputation off reproducing disaffected, hipster malaise. In “Shoplifting from American Apparel,” Lin inserts himself as the protagonist Sam, a vegan writer who lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Sam often feels vaguely “fucked” in a generally affectless world of name brands, Gchat and Facebook. He shoplifts a couple times and winds up in jail for a night. Occasionally, he mindlessly mistreats others for a laugh: inexplicably throwing a friend’s drink, hitting someone with a stick, and ordering someone to jump over a bush. The entire narrative is as disconnected from the larger society as the characters are from each other, and therefore it reads as a mimetic rendering of a soulless world rather than satire. New Tao Lins publish every day, feeding the culture’s desire to watch its own destruction.”

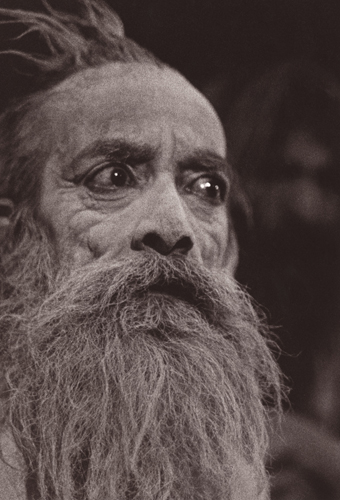

Alvin Langdon

The Adorno quote at the top is relevant here, and often, I think, misunderstood. There were plenty of SS officers who could play Beethoven or Bach on their violins, and many were great lovers of high art. That is not the issue. The issue is that a society which degrades the idea of art and culture, and the sense of redemption through awakening, through collective trust and hope, is one that finally can no longer respond to the stories of the world surrounding it in any manner other than sarcasm and insult.

I came across this story this week; http://tellmenow.com/2014/04/women-prisoners-sterilized-to-cut-welfare-costs-in-california/

I think the reality of the U.S. gulag remains obscured, opaque, and remote to the average American, if we can even use that term.

http://aeon.co/magazine/being-human/why-solitary-confinement-degrades-us-all/

Why are these realities not in network TV? That is worth thinking on. The torture and killing seen on Hannibal, however beautifully realized, still premises violence on pscyhotic *individuals*. We do not see the forced sterilizations of women in the California prison system, we do not see the charred body parts of children in Yemen, or the horrific birth defects caused by depleted uranium, in the war zones of the U.S. military empire. However much legitimacy I can squeeze from a show like Hannibal, in the end it is deflecting and shielding the reality of U.S. terror, and creating lurid villains as a way, conscious or not, to deflect the gaze from the greatest villain of all, the U.S. government. Who has more blood on his hands, Hannibal Lecter or Dick Cheney?

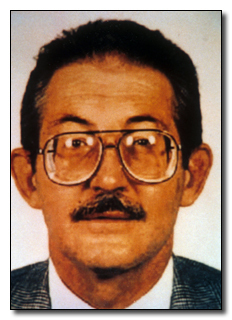

Alina Szapocznikow

But, Cheney is finally, so unremittingly banal, so lacking in Shakespearan scope, that one feels sympathetic in the desire for the inventing of a Hannibal Lecter. In a sense, if ABC’s Hannibal really had the courage of it’s conviction, or probably, rather, if it was at all aware of them, then the landscape of Hannibal could well begin to enclose the Dept of State, Rumsfeld’s wing of the Pentagon, and would begin to find in its creation of *evil* the authentic metaphoric expressions of, say, a Jonathan Pollard, or Aldrich Ames, or Richard Holbrooke…and there would be a knocking of the White House gate. In other words, the individualized landscape of Hannibal becomes reactionary by virtue of never exploring the outer real world. Or, rather, implying an outer world of stability and sanity.

Aldrich Ames

Our mortality is the most serious of subjects, and I might argue that the manufacturing of fear is one way, one adjustment, instinctively, by the propriator class, to change the subject. From the existential abyss, to simply projecting such anxiety onto figures such as Lecter, of whatever weekly serial killer crops up on a half dozen shows running right now. Time will tell if Hannibal can even reach the level of Grimm’s fairy tales, or Hoffman’s Der Sandmann. The question really comes down to what artworks manage to resist reification, since in a sense, all of them are commodities.

But when examining cultural product today, it’s impossible to avoid the effects of mass marketing in the construction of the ‘real’. I think even I have underestimated the influences of authority. That most technology, by virtue of the instructions needed to operate it, instills a sense of following orders. Together, the role of learning instructions (Ikea like) and the erosion of community vernacular and grammar, the populace from an early age are encouraged to watch for what to do, and to wait to be told what to do, and to simply, not question things. The language of marketing is, additionally in fact, designed to create muteness. Popular culture, and most TV series, play upon the idea of familiarity. Except its a false falimiarity. A sort of false recovered culture memory.

Hannibal, CBS TV, 2014

Another show, From Dusk to Dawn, (El Rey productions, via Miramx and Netflix) is a spin off from the decades earlier Robert Rodriquez film, co-written by Quinten Tarantino. It is another example of the familiar comic book world. The basic incoherence of the narrative, the saturated pinks, and reds, the anti-freeze greens, and the essential emptiness and focus on style, suggest, perhaps, the inner life of the U.S. The *dead now* if a film strip, might feel a lot like From Dusk to Dawn. In an early episode one of the locations is a border motel. Now, this is a familiar image, and a sort of ersatz archetype. There is NO one Southwest border motel. There are many, sort of. There is no single image that comes to mind, only a generality, a sort of memory trace, which in fact is only a dim ‘feeling’ of something associated with ‘noir’. And as such it triggers a vague style code trace,a regression, and what is familiar is the falseness of the memory. The feeling of this triggering effect is familiar. The audience really thinks, oh, Ive had this indistinct association before…..I think….sort of…..enough to place the image in the correct general category. Sharing and collective experience has been narrowed down to shared aknowledgment of popularity. Game of Thrones….oh, that’s a really popular show, ergo I need to watch it. The southwest border motel stands in for historical meaning. It is “style”, nothing more.

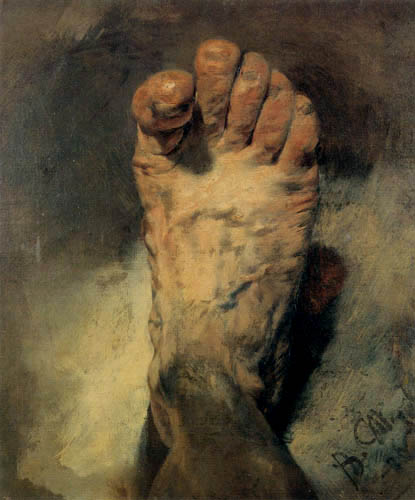

Nathan Oliveira

F.R. Leavis when writing of Alexander Smith’s poem Barbara, said; “It doesn’t merely surrender to temptation; it goes straight for a sentimental debauch, an emotional wallowing, the alleged situation being only the show of an excuse for the indulgence, which is, with a kind of innocent shamelessness, sought for its own sake. If one wants a justification for invoking the term ‘insincerity’, one can point to the fact that the poem clearly enjoys its pang…”. Leavis later, when speaking of Conrad, adds:

“Creative art here is an exercise in the achieving of precision (a process that is at the same time the achieving of complete sincerity– the elimination of ego interested distortion and all impure motives) in the recovery of a memory now implicitly judged-implicitly, for actual judgement can’t be stated – to be, in a specific life, of high singificance.” Disciplined memory, this is what can happen only when the writing is connected to the material world, and the material forces that shape it. Not in that reductive Iowa Writers Workshop way of eliminating ideas, but of placing ideas in a concrete context. Of making ideas into material, in actual emotions, into dreams, as well. Nothing is so real as a dream. So foreign is this today, in a culture saturated with the inauthentic, with snark and sarcasm, and more, with self branding, and with an advertising of self, with just the commodity addictions, that I think it’s all but forgotten as a way to read or view. Still, yes, it is useful to know WHICH border motel, and to know for whom that knocking of the gate serves as a wake.

Fantastic John. Because I’m consumed with my music at the moment, I can relate all that you speak about (even location specific sets like a border motel) to the art of writing songs. In that article that referenced David Foster Wallace I was struck by the beauty of the song mentioned –

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows my sorrow

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Glory Hallelujah

The seemingly different but connected lines here reflect to me Leavis’ thoughts on Conrad. Specificity can be a kind of precision that allows work to flow more freely. But it also seems to have it’s unfortunate parts. How does one write about WHICH border town without appearing to be delivering a forced message.

I find the branding that invariably happens and the self promotions of which I can’t seem to escape myself really do deaden the process a good deal. It’s hard to work within an industry so bent on destroying collective memory and political history. Alas the passion for the work keeps me going. Thanks for your thoughts and your dedication to keeping up this blog. Many good blogs seem to die out too soon for lack of comments or blog traffic.

Brilliant work, John, thank you. What strikes me about violence in former contexts and now is that where once it was a matter of tragedy and moral crisis and now it is a matter of mechanism.

Interesting jack, because American roots music used to be so grafted to regional specifics. Baton Rouge, or Vicksburg, train wrecks and storms. But just the poetry of place names was so resonant. When corporate interests took over, there was a conscious elimination of such specifics. The idea was to appeal to the largest possible audience. Now, that doesnt even make sense, but such is the mind of marketing experts. But i think the more difficult topic is self branding in a sense because the entire apparatus of cultural commodities is greared to brand awareness, and Naomi Klein’s No Logo remains a really cogent analysis of the shift from advertising to branding. As for the blog, its interesting there are so few comments because I get a lot more traffic than one might expect. But I think its the nature of the postings, for a variety of reasons, that sort of stops the usual comment formula. Also, I guess I write longer postings than a lot of other blogs. i dont know. Anyway, thanks.

@richard……. yes. The tragic is predicated on the revealing of something hidden within the violence. Its complicated, and not easy to discuss in short form, but the pop violence is now almost the opposite; life is not thought of as having value….or rather only certain lives. And certainly killing, through all of this, is being normalized. I think its interesting and maybe Ill write about this soon, the entire spin off phenomenon….bates motel and fargo etc. All these shows come with a built in familiarity. They need no introduction. The story is already known…..Bates Motel and Hannibal are actually prequals……so the ending is already there, and what is being filled in is therefore sort of doubly familiar. But its more than that, its also this invitation to the culturally aware audience to sort of “enjoy” the inside joke somehow. I really think this goes back, as I wrote before, to this shift, culturally, under Reagan.