Mose Tolliver

“This overlooks the fact that both commodity exchange and gift exchange are encoded. There is no transparency about gift exchange, whether it is viewed as a sequential chain or as a strategic set of acts by particular agents; in either case gift exchange needs to be decoded as a system of obligations. The effects of the two forms of encoding are quite different, however, with respect to their con- sequences for remembering and forgetting. The mode of encoding operative in gift exchange precipitates a form of cultural remembering; the mode of encoding operative in commodity exchange generates a form of cultural forgetting.”

Paul Connerton

“If only we had a name for the new form, which is no longer a form.”

Ernst Bloch

The most pronounced trend in Hollywood storytelling over the last, lets say four decades, but maybe it is most acute over the last twenty years, has been the privileging of surprise. Or what is often called *reveals* in the corridors of mass culture’s decision makers. Increasingly the need for surprises in plot has meant that character development is, essentially, discarded. If the construction of character is too complex, the execution of these *reveals* becomes too hard. And audiences for U.S. TV in particular now anticipate these *reveals*. So and so isn’t really a lawyer or doctor or CIA agent, but in fact is the serial killer or space alien, or the long lost son of the patriarch etc etc etc. The emphasis is so weighted toward plot now, at least in U.S. television that new forms of short hand have evolved, probably without much conscious consideration, that serve as generic markers for character. The sheer volume of product has served to instill a kind of signifier radar in the audience. The audience recongizes the sub genre at work and I suspect is almost never actually surprised by any of this plot mechanisms. And this all started in the 80s, which is when I started to hear much of a new vocabulary in writer’s conferences.

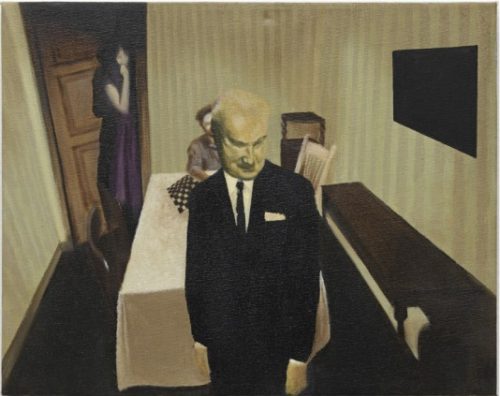

Alejandro Campins

Doug Eboch recently wrote of several new trends:

“1. Simultaneous Development. With so much at stake on big franchise movies, recently some studios have begun hiring multiple writers to work on screenplays at the same time. These writers are not working together, they are each writing an individual script. The studio will then decide which it likes best (and probably cannibalize good ideas from the others).

2. Shared Universes. It’s no secret studios love franchises. Successful franchises like The Fast and the Furious series, Hunger Games series, or Harry Potter series can keep studios financially sound for years. The new trend is franchises built around shared universes – story worlds that can support films about multiple characters and stories, thus creating a “brand” that draws audiences even when the movies are not traditional sequels.

3. Feature Writers’ Rooms. This is related to the “shared universe” trend. With studios making multiple movies set in the same world, the feature films occasionally resemble television series – coming this summer, episode twelve of Marvel’s superheroes! And the feature world has started borrowing another television practice: writers’ rooms. Teams of writers have been formed to shepherd the development of stories in the Transformers world, Star Wars world, and the upcoming series of movies featuring Universal’s monsters.”

Now there are rather obvious economic trends, too. One is the ascent of *trans media* in storylines. The recent TV show Skam (Norway) about high school students relies heavily on social media to background story lines and character. The audience has to access facebook to complete the holes in the viewing portion of the story. But these are all reasonably well known trends. And really, looking at film from as recently as the 1980s, one sees that often the primary action or dynamic of the story happens somewhere around page fifty (Scott Myers uses Karate Kid and Witness as examples. Harrison Ford doesn’t even get to the Amish farm until minute 36. And Miyagi doesnt start teaching Daniel until minute 55). One critic called today’s writing the outside-in school. But its much worse than that. The outside, the world of the story, is today often so shrunken that the narrative unfolds in a universe of about twenty humans.

Nicholas Alan Cope, photography.

The shrunken world effect is one in which the outside world, which in theory is where the writing is focused since characters have ever less inner life, is devoid of actual humanity. It is almost as if there is a tacit acceptance by the TV and filmmakers that the passing world is backdrop. A cut out synthetic simulacra that is there to pass as reality. But the fact it doesn’t make much effort to pass means that the subjective experience of watching such shows and films is one in which disinterest colors this synthetic backdrop. The producers of TV and film, in Hollywood, are therefor creating non characters who must surprise the viewer by not being what they say, and non world backdrops. The audience learns not to invest too deeply in character because it’s likely not real. Couple this is the change in script descriptions from the 70s on into the 80s, and today — the average description of action was once 5 to 7 paragraphs, and is now 3 to 4. And action starts the film, an action that signals theme. And also signals the sub genre — announcing to the audience what is expected of their viewership.

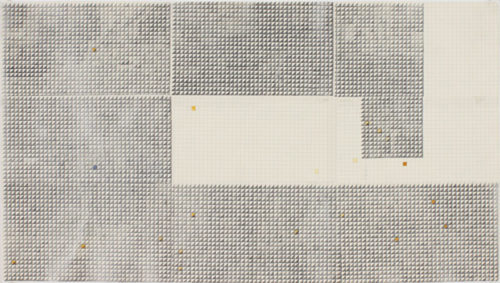

Haleh Redjaian

Mass cultural product now encourages indifference to human character. Now the influence of screenwriting books, starting with Syd Field, and more significantly, probably, with Robert McKee, had less effect on writers, good ones anyway, but a lot of effect on studio readers and the so called D-Girl culture of film and TV development. Readers and executives began to read scripts to see how closely they followed Field’s *paradigm* or McKee’s formula. The truth was that you could see what you wanted to see in almost any script. But it served as a justification for ignorance. For none of these decision makers in Hollywood read. None of them. Big agents and producers, executives and show runners even, none of them read. They read script. They may have read a few required books in college, but they certainly don’t read now. I mention all this, and I’ve discussed a lot of it before, or aspects of it, because there has been a new intensification of the non-quality of narrative. Without wanting to sound cute, it is non story, non character, and non world. For they are interdependent. Marvell Comix and DC work so well for Hollywood because these are not real characters, they are comic book characters (once a pejorative observation). In a sense the *reveals* work best when the audience is only mildly surprised. To be hugely and genuinely surprised induces a kind of suspicion. Often a mild sense of paranoia. Having no surprise doesn’t work either. No surprise means its simply too predictable. Today’s audience expects and anticipates these reveals, but they don’t want to be ahead of the writer. Not completely anyway. They want the story to surprise them…a little. Or rather, to be more precise, they want characters who are not fully characters to surprise them by turning out to be someone else who is also not really a someone. They want the actual narrative to remain familiar. There has evolved a kind of cultural familiarity that is specific. It is the recognition of style cues and allusions to brand and trending vocabulary. The growth of brand mentions and allusions to pop culture has grown to the point where often entire conversations revolve around discussions of earlier TV shows. Often ones fifty years old. To mention Karate Kid again; a reference to Mr Miyagi has taken on all sorts of associations, but primarily as a tribal identifier. It is a white male under forty reference. An allusion to, say, Pretty Woman would elicit the expected nods of recognition from a mostly female white audience in their thirties. And so on, and on and on. To watch, say, an American film from the 1940s is to suddenly be dropped into a world of language and discourse that seems almost alien today. Hence the treatment of old films as kitsch. Always, as kitsch. As quaint. For today’s audience for the most part can’t *read* those films with any genuine engagement with character. To watch, say, All About Eve (1950) for contemporary audiences means having to reduce the experience to Bette Davis kitsch, and maybe to know Marylin Monroe had a tiny part in it. The more tragic material of classic noir from that era will suffer the same treatment. A film such as Criss Cross (1947) is simply impenetrable. Sweet Smell of Success (1957) is so foreign in sensibility that I wonder what audiences today would make of it at all. Sweet Smell of Success is a perfect study for comparison, though. A claustrophobic world of smokey jazz clubs and smokier bars, and crowded New York sidewalks, the film focuses hugely on just two men: J.J. Hunsaker (Lancaster) and Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis). The people passing on the streets or sitting in the club are treated as both anonymous and menacing. But also as somehow near tragic. Clifford Odets wrote much of the dialogue, and co authored the script with Ernest Lehman. The world is palpable, it is always there pushing against the two men who act out the Oedipal master slave dynamic, one with lacerating sexual subtext. But the world never recedes. One never feels the world is twenty people, the world is a kind of impossible.

Sweet Smell of Sucess (1957) Alexander Mackendrick, dr.

Roger Ebert wrote : “Sweet Smell of Success” is one of those rare films where you remember the names of the characters because you remember them–as people, as types, as benchmarks.”

I would argue you remember the world, too. You remember those you don’t get to know. But you have felt their presence. And it is the genius of cinematographer James Wong Howe to constantly make one aware of who hasn’t been introduced. But all of this is look at the levels of cultural catatonia that have taken hold of contemporary daily life. If one *reads* only backdrop, and not a world, how much easier it is to ignore real worlds. Yemen, a massive war crime taking place in real time is ignored. It is not even backdrop, for the backdrop is one manufactured by media — one that also shapes the subject position of those doing the ignoring. And one aspect of this is to shape dissent — a faux dissent in which a *new* left, branded and capitalized, in their guise as reasonable and adult, make sure to police real dissent more ruthlessly than even conservatives or liberals. This is the left that makes sure to denigrate Chavez and Maduro, to label Syria a *regime* and laugh at those crazy North Koreans. For this is proof that they have a seat at the table of reality. If Rachel Maddow is the poster girl for shaming those deemed not adult, then magazines such as Jacobin are the responsible critics of reality, like Maddow, or like (pick one) Keith Olberman or David Brooks or any of a half dozen TV pundits. This is a manufactured reality, that is of course only synthetic backdrop. And films such as Sweet Smell of Success take on importance in this light. Not for theme or message but because they reflect a world. A genuine world. THE world. For there is a world. And to have to spell that out speaks volumes about the cultural catatonia I posit.

Yves Dana

“‘The metropolis and mental life,’ published in 1911. Simmel there contemplated how we might respond to and internalize, psychologically and intellectually, the incredible diversity of experiences and stimuli to which modern urban life exposed us. We were, on the one hand, liberated from the chains of subjective dependence and thereby allowed a much greater degree of individual liberty. But this was achieved at the expense of treating others in objective and instrumental terms. We had no choice except to relate to faceless ‘others’ via the cold and heartless calculus of the necessary money exchanges which could co-ordinate a proliferating social division of labour. We also submit to a rigorous disciplining in our sense of space and time, and surrender ourselves to the hegemony of calculating economic rationality.”

David Harvey

Now people often talk about paradigm shifts when speaking of cultural epochs, and often the most recent presumed shift was from modernism to post modernism. When this occurred is much debated. But lets say it occurred somewhere between mid sixties and late seventies. I would like to argue that a much more significant shift has occurred in the last fifteen years. I would say the precursor to stage one of this shift was perhaps taking place in the mid eighties, but the actual shift was in full swing by 2003 or 2004. And I don’t like to talk of linear historical periods in this fashion, but for the purposes here I’d only argue that the cultural catatonia of which I speak — that which has rendered the world view, the perspective of the majority of consumers and managers, and even a fair number of the lumpen proletariat, numb and blind, deaf and confused, reached operative status early in this century.

Marvin Stupich, photography (Carbon County, WY 1998).

But to grasp this new cultural stasis, I think its useful to reflect on a few points about modernism.

“The reordering of perception in the metropolis of 1900 parallels the reordering of time and space in our own time by a whole new set of digital media and related

new social practices. Again, compression and miniaturization are at stake in different forms, and their effects on the human perceptual apparatus are the fulcrum of a wide- ranging debate about the benefits and downsides of our contemporary media culture.”

Andreas Huyssen

“What it [The Trial] conveys above all else, he [Brecht] thinks, is

a dread of the unending and irresistible growth of great cities. . . .

Such cities are an expression of the boundless maze of indirect

relationships, complex mutual dependencies and compartmentations

[sic] into which human beings are forced by modern forms

of living.”

Walter Benjamin (Diaries 1934)

Joe Deal, photography (Diamond Bar, CA 1980).

Huyssen’s recent book (Miniature Metropolis, ) is very good and very perceptive in terms of how to view the early onset of modernism and how the fragment and epigrammatic writing of countless early modernists (and late, really) conveys something of an unconscious re-organization of perception, but also of a tinkering with ideological perspectives (I should note that Huyssen is one of the most referenced and quoted historians alive today and yet is rarely given his real due as a thinker).

The rise of modernism ran alongside the rise of the city. Urban visuality was something unprecedented and it also somehow fit with Freud and the psychoanalytic. The end game for modernism, in architecture anyway, was signaled by Charles Jencks, and the dynamiting of the Pruitt Igoe Housing tract in St Louis. And the amazingly influential Learning From Las Vegas, by Robert Venturi (also 1972). I have always considered the photographers of the New Topographics movement (informally labeled) that included Lewis Baltz and Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke and Robert Adams, to be among the most significant chroniclers of a last stage of American culture, soon to pass away. What they saw in those photos from the 70s, mostly, was the last gasp of something sincere and diseased, honest in its own way, but mutilated, too. Thus the 1970s feels today like the post script to something, more than the introduction to anything. There was a political pessimism in that show (1975), and it was less the erosion of Nature by man than it was the loss of the human in nature. It was not a green statement, it was closer to a religious statement in the sense that there was now the inescapable in the form of the everyday. It was Sigfried Kracauer who, I think, first saw photography and cinema destroying memory. Kafka himself (as Huyssen notes) wrote that…

“One photographs things in order to get them out of one’s mind. My stories are a kind of closing one’s eyes.”

Giulio Frigo

Huyssen, writing on Kafka:

“Certainly not grounded in the social reality of the earlier nineteenth century novel, but grounded instead in the new reality of statistical averages, of the men and women in the mass. Here it appears as if capitalism itself, elsewhere bound to the frantic pace of always changing fashions, has come to a dead end, as if what Benjamin called the “sexual appeal of the inorganic”— that is, fashion— has been deadened, “no longer wearable.” The visible world locks its meaning behind surface appearances such as clothes, but they become worn out like the individual physiognomies of those who wear them. The organic merges with the inorganic in clear opposition to all the vitalist celebrations of life around 1900. The visible surface is all there is, and it is photography and film that reduce the modern urban dweller to two- dimensional surface appearance.”

The visible world locks its meaning behind surface appearances. And yet it is more than that. For this visible world was already eroded and distanced. It is interesting that Kracauer criticized Benjamin for ‘turning away from the immediate’. But this could be said of countless thinkers and writers of the period before WW2. There was already a sense of horror in the banality of urban daily life. And it cut across nations and cultures. Benjamin called Kafka the last storyteller. But that needs clarification, I think. Kafka was the last link to the role of stories in human communities, and by extension in cultures. The Universalizing tendency of later 20th century fiction (a decontextualizing) favored an almost performative role for the author. I think a small few fiction writers came out the other end, and in part this was by removing the structure of narrative as it was known since the 18th century, and writing what are expanded epigrams. Expanded miniatures, if you like. Writers such as Thomas Bernhard, W.G. Sebald, and Peter Handke. Handke also wrote plays, and is perhaps firstly a playwright. But Sebald was writing as a voice in the Universalized present, and paddled upstream through the synthetic backdrop. Heidegger was a fascist, an authoritarian, and hence perhaps saw more clearly what he called the ‘standing reserve’. The first three writers I think of are all German language writers. I’m not sure exactly what that means.

James Wood compared Sebald to Bernhard, Handke and Kafka. No surprise. I found this out after writing the above paragraph. But then it is probably sort of obvious.

“From his student days onward, Sebald was a deep reader of Adorno, and the passage might be an epigraph for all Sebald’s writing. What animates his project is the task of saving the dead, retrieving them through representation. That paradox is most acute when we look not at words about people but at photographs of people, since they have a presence that words cannot quite capture. As Roland Barthes writes in “Camera Lucida,” photographs declare that what you’re looking at really existed, and as actuality, not as metaphor.”

James Wood

Sebald, like Benjamin, and quite a few others, was fascinated with postcards. Perhaps it is the world is now very much like a postcard of a world.

“The books he wrote are about living in the past, and what it is that conspires to make this a way— maybe the only bearable or defensible one—of living in the present.”

T.J. Clark

That is both right and not right. It sounds good, though. Sebald, like Bernhard, and like Handke, did not live in the past, but transcribed the nature, a prophetic nature, of suffering that saw was inevitably going to grow worse. Lynn Sharon Swartz wrote ..after Sebald’s death….“He was the writer we could least afford to lose.” I hate that use of the word *we*. That rhetorical gambit is employed a lot these days. Reminds me of the Lenny Bruce joke about The Lone Ranger. Tonto and The Lone Ranger see marauding Indians ahead….TLR says ‘I think we’re in trouble, Tonto’. And Tonto answers ‘what do you mean “we” white man?’

Giacomo Brunelli, photography.

One thing that separates Sebald and Bernhard and Handke from most contemporary writers, those who at least overlap with post modernism, is a preoccupation with death. And I want to return to that but it is not quite the real topic here. James Wood, in a review of someone (I didn’t write it down) observed something about first person narration..

“Most first-person unreliability in fiction is reliably unreliable; rather mechanically, it teaches us how to read it, how to plug its holes. Double unreliability—or unreliable unreliability—is rarer, and more interesting, because it asks much more of the reader.”

But what he was referring to above is more the *unreliable narrative voice* — an increasingly popular stylistic trope. The liar who cant but reveal the truth. Except most ‘unreliable narrators’ do not ever get to the truth. And it is interesting to compare first person narration in prose with voice over narration in film. Much noir had cynical voice over narration, but usually with an eye cast backward. That voice paid a price. The confession came with a cost.

Jerome Lagarrigue

That voice, the weary noir detective, cannot almost be duplicated today in film narratives. For the idea pushing that story is the pursuit of truth. And nobody any longer privileges truth above falsehood. Neither exist, really. Walter Benjamin in one of his several essays on Kafka wrote…“In the stories which Kafka left us, narrative art regains the significance it had in the mouth of Scheherazade: to postpone the future.” That is no longer what narratives do. There was a last link to something of community, of antiquity, in Kafka. I suspect it is why he continues to have such a hold on the contemporary reader. So much is written about Kafka today, perhaps only Shakespeare drives such a cottage industry in criticism. The world Kafka describes, or writes within, is as different from today’s world as that which Dante wrote about. When Adorno wrote his parents from California, he observed “One actually has the feeling that this part of the world is inhabited by humanoid beings, not only by gasoline stations and hot dogs.” The current spate of android film and fiction is not an accident, it is the gnawing fear of everyone living in the Capitalist West. And this paranoid fantasy continues to crop up as a way to avoid the more frightening reality of a world without even humanoids or robots.

Two recent films are illustrative of some of this. The Mummy, a film that got scathing reviews, starring Tom Cruise, is not watchable. I watched 15 minutes of it — 15 minutes of my life I will never get back. But it is telling that early in the film a group of *Iraqi insurgents* are killed. Slaughtered. What that term might mean to the producers and writers of this film is anyone’s guess, but that a war that has all but destroyed an entire country should be so offhandedly and casually used as a device for Cruise cartoon heroism is rather amazing. Then there is Alien: Covenant, the new Ridley Scott entry in this well worn franchise. It is a film that got mostly rave reviews. A film so empty, so devoid of character, that I was numb at the end. And of course, note the reveal (surprise) at the end (echoing another sci fi film from last year, Life, directed by Daniel Espinosa). And the two leads in the film, both played by Michael Fassbender, are androids ! It is almost a curious reversal of Jeckyll & Hyde. In the Stevenson story the battle is over man’s soul, in the Scott vehicle it battle over the software of the android.

Kevin Yates

David Harvey, in his book on post modernism, in a chapter on cinema, looks at an early Scott film, Blade Runner. A film about androids, too, essentially.

“The replicants exist, in short, in that schizophrenic rush of time that Jameson, Deleuze and Guattari, and others see as so central to post modern living. They also move across a breadth of space with a fluidity that gains them an immense fund of experience. Their persona matches in many respects the time and space of instantaneous global communications.”

Sam Jinks

The desire for android life is born of this sense of inadequate speed and processing, and the idea that text might be just uploaded and do away with the messy business of actually reading. Androids that are *better* than us. They don’t feel. Feeling is imperfection. This is the constant subtext to nearly all android narratives. Hollywood treats emotion as a trope in sentimental melodrama, and token asides are handed out about the value of emotions, while always simultaneously undermining the idea of emotion by making the emotionless man heroic. Now there is also the fact that androids never die. Much like vampires.

Allow me to quote James Wood again….“At the service, I reflected not only that a funeral is a liturgical home for the awful privilege of seeing a life whole but also that fiction offers a secular version of that liturgical hospitality. I thought of Walter Benjamin’s argument, in his essay “The Storyteller,” that classic storytelling is structured around death. It is death, Benjamin says, that makes a story transmissible.”

Death is now very much signified by forensics. I cannot think of a recent film in which there was not a cadaver being dissected. Forensics is the new rationalized process of death. A funereal rite without funeral. The ordinance, or ceremony is the weighing of organs and the analysis of of the contents of the dead’s stomach. It is dispassionate and objective. Death is catalogued. The forensic professional is also a part of the authority structure. Pathologists then are a voice of institutional authority regards death. And by extension about life. One’s life is being *told* via the analysis of the bruising on a thigh, stomach contents and contusions to the scalp. Where once the Knight Errant detective was on a private crusade for truth, for *the* truth of a crime, a life, the pathologist is simply reconstructing information and making it into a backward looking story. The police enter to interpret the information. Much as priests interpret signs from God.

Takashi Homma, photography.

The characters of contemporary drama in TV and film (from Hollywood anyway) are non characters who occupy their approved space in this backdrop in which most of global humanity is erased. The loss of real worlds, certainly of worlds with people in them, is linked in complex and I think at times very obscure ways with the nature of photography.

“The portrait-photograph is a closed field of forces. Four image-repertoires intersect here, oppose and distort each other. In front of the lens, I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art. In other words, a strange action: I do not stop imitating myself, and because of this, each time I am (or let myself be) photographed, I invariably suffer from a sensation of inauthenticity, sometimes of imposture (comparable to certain nightmares). In terms of image-repertoire, the Photograph (the one I intend) represents that very subtle moment when, to tell the truth, I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is. I am becoming an object: I then experience a micro-version of death (parenthesis): I am truly becoming a specter.”

Roland Barthes

Hiroshi Sugimoto, photography.

There are crowds, of course, in film. And this is one of the unsettling aspects of film and TV today. Crowds are treated as one treats refuse or slag heaps — scars on a landscape. There is the subtle environmentalist subtext in this, too. This is part of the neo-Malthusian overpopulation meme; in other words humans are a danger to the planet. This bears the creepy sentimentality of new age-ish bathos, all the Gaia and Mother Earth themes that barely mask the hostility to those classes beneath you. The affluent classes are the most virtuous regards Nature today. I recently had an argument about the very rich Marin County of California and their request for an exemption from having to provide affordable public housing. The argument was to preserve the 80% of that county put aside from development and left wild. How can anyone argue against preserving nature they ask? Marin County is, in a sense, the living version of the synthetic backdrop I speak of .. and the ironies are many. It is a place created in the mind of white cultural gatekeepers. One could do an entire monograph on the treatment of public park land in the U.S. For in microcosm one would see all the exclusionary and racist sentiments of the ruling class at work.

But my point is really about narrative. The narrative of mass culture has become the narrative of daily life. Crowds are menacing, and must be photographed. Surveillance is the safeguard against mass organizations. The micro deaths of photography can be felt on social media, of course. Facebook is akin to Victorian death portraits. The post mortem photography of Victorian England (and the U.S. to a lesser degree) are reproduced in a fashion on social media.

Phillip Kwame Apagya, photography.

Barthes noted that society makes one an object in photographs of ourselves, but we, the subject, experience it as Death. Sartre famously said “Newspaper photographs can very well ‘say nothing to me.’ In other words, I look at them without assuming a posture of existence. Though the persons whose photograph I see are certainly present in the photograph, they are so without existential posture, like the Knight and Death present in Durer’s engraving, but without my positing them. Moreover, cases occur where the photograph leaves me so indifferent that I do not even

bother to see it ‘as an image.”

Social media is how narrative is written today for the average Westerner. Memories are rearranged and trotted out at the desired time. Text is truncated, but whatever is posted can be *shared*. These words are insidious. Imagine facebook without images. What would change in the writing? Text is scanned in cursory ways, and videos are *read*.

“The past life of emigrés is, as we know, annulled. Earlier it was

the warrant of arrest, today it is intellectual experience that is

declared non- transferable and un- naturalizable. Anything that

is not reified, cannot be counted and measured, ceases to exist.”

Adorno

Ursula Palla

The emigre’s past is background…as Huyssen notes. Background is then that which ceases to exist. The background of mass cultural entertainment is meant to not exist. Adorno saw fascist violence in the small changes of daily life. “What does it mean for the subject that there are no more casement windows to open, but only sliding frames to shove, no gentle latches but turnable handles, no forecourt, no doorstep before the street, no wall around the garden?” Hollywood film and TV produce characterless streams of image in which the present is subjected to forensic abuse, and the turning of life into data. Lives are destined for the pathologist’s table. Life becomes information for processing. And these image streams are set against the background that is meant to not be seen except as backdrop, not be reflected upon, and in which humanity is absent.

Walter Benjamin, on Kafka:

“‘The object of the trial,’ he writes, ‘indeed, the real hero of this incredible book is forgetting, whose main characteristic is the forgetting of itself…. Here it has actually become a mute figure in the shape of the accused man, a figure of the most striking intensity.’ {} What has been forgotten—and this insight affords us yet another avenue of access to Kafka’s work—is never something purely individual. Everything forgotten mingles with what has been forgotten of the prehistoric world, forms countless, uncertain, changing compounds, yielding a constant flow of new, strange products. Oblivion is the container from which the inexhaustible intermediate world in Kafka’s stories presses toward the light. ”

Excellent piece John. Among those others fascinated with postcards was Kafka himself; notably he took from a postcard’s caption “Nature Theatre of Oklahama” for Amerika, a work for which photographs are of considerable importance, a caption accompanying a photograph of a lynching. Such postcards were widely available, sold for profit alongside any number of less morbid mundane items, and it’s not difficult to imagine the immense psychic impact encountering such an artifact would have.

Mr. Steppling, your essays are ones that motivate me to read more than I already do because they are often full of references that push my knowledge of literature, and its criticism to the limit such that I feel I should read up on some of your references. Reading your essays is a bit like reading Saul Bellow’s novels or essays in that they are often sure to contain references to some unfamiliar literary, philosophical, or literary criticism work. The art works you post throughout them are also wonderful, and those too push my knowledge of visual arts to the limit. Thanks, I enjoy being challenged. I am very grateful that I discovered you, and your site when I read a post of yours on Counterpunch, and I look forward to reading “Sea Of Cortez And Other Plays” which I will purchase today from Barnes & Noble. I’ve never read plays before, preferring to see them acted on stage since we have a thriving theatre community in Chicago.

I am a close reader, and your seeming refusal to use contractions is something about which I am curious; cant, lets, and its are a few examples I noted in the past couple of essays. I am guessing that they are just typos, but I feel compelled to ask, because you are neither a careless thinker nor writer, are they? I realize these essays are a labor of love, and cranking them out is no small task, so any typos are obviously forgiven, but I am curious about them. I also have a request. Many reporters, and other writers often link to their own works, or works of others by using Amazon. I personally find the Amazon business model incredibly abusive, and frightening on a number of levels; it’s essentially the Walmart model applied first to books, other works of art, consumer products, now grocery, and increasingly mass media. I hope you will consider linking to Barnes & Noble instead. It’s a better company, and the bio of the company’s founder is impressive.

This essay is a bit bone-chilling. It’s also a bit akin to a long, sophisticated critique of American fast food in that its focus seems to be primarily on the garbage that comes out of Hollywood, much of which winds up on t.v.. At least ninety five percent of what has always come out of Hollywood is garbage, and even the titans that ran it in the early part of the last century realized that which is why they worked to recruit the Hemingways, and Fitzgeralds of that world to produce content for them. The old Hollywood studio system was not much more than a sophisticated, artistic application of the Capitalist sweat shop model of manufacturing, just as was the Brill Building in NYC for music. Artificial intelligence is now being designed to remove human labor from as many roles as possible, for increased profits of course, and the arts are not an exception, or exempt. Other than as a child before entering middle school, I never watched much U.S. television. My parents understood it to be garbage, and it was rarely used as a baby sitter as it was in the homes of many of my friends. For the few years that I had access to cable t.v. when I rented a condo that had it, I found surfing the hundreds of channels for something decent to watch like driving past suburban American strip malls looking for something interesting to see, or decent to eat. That Americans get their news from television, and the rest of corporate media explains much about why the world is the way it is. There is little-to-no insightful, honest political analysis, and even less cultural analysis provided by corporate media. I long ago closed my Facebook account because I detest censorship, and it strikes me as a platform for the slightly narcissistic, and trivial. Perhaps a better analogy for Facebook, or Farcebook as I prefer to call it, than Victorian death portraits would be death masks. Portraits take the talent of an artist, whereas smearing plaster on the face of a corpse of a talented composer like van Beethoven did not. Crowd sourcing narrative does not work.

“Life become information for processing.” There is no doubt that information technologies, and other rapidly developing technologies of robotics, and genetic engineering, while so beneficial to humanity in many ways, are likely to result in tyrannies, and horror scarcely imaginable. The impacts of technology on the arts are nearly impossible to imagine. I’m not encouraged that the benefits of technology to the arts will outweigh their drawbacks. The recent articles about, and photos of the super-muscular genetically engineered dog “made” in China should give anyone more than a bit of fright. The Internet has a paradoxical effect of both attenuating, and enlarging community. It will be an endless source of research for sociologists, and psychologists.

Pruit-Igoe from Koyaanisqatsi

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nq_SpRBXRmE

Oops. One more cut.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNNJrHR53ZA