Jean Charles Blais

“A long time ago when I was writing for the pulps I put into a story a line like “He got out of the car and walked across the sun-drenched sidewalk until the shadow of the awning over the entrance fell across his face like the touch of cool water.” They took it out when they published the story. Their readers didn’t appreciate this sort of thing — just held up the action. I set out to prove them wrong. My theory was that the readers just thought they cared about nothing but the action; that really, although they didn’t know it, the thing they cared about, and that I cared about, was the creation of emotion through dialogue and description.”

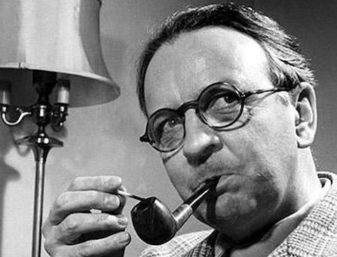

Raymond Chandler

“Great works wait. While their metaphysical meaning dissolves, something of their truth content, however little it can be pinned down, does not; it is that whereby they remain eloquent.”

Adorno

“The human is indissolubly linked with imitation: a human being only becomes human at all by imitating other human beings.”

Adorno

Adorno’s late lectures on moral philosophy are worth reading again, I think and if you’ve not read them, then I’d suggest you do. But one of the key points of the entire discussion has to do with the distinction between an ethics of conviction and an ethics of responsibility. Adorno saw that there was an insidious tendency in modern society to see praxis as superior, and that putting aside for a second that question, that the result was often the borrowing of a practice ready made that was sourced by something authoritarian — an ideology linked to Nationalism or its substitute — and that this then rendered in ways that deny the possibility of real freedom. And that, he concluded (like Kant) that true practice was not possible without its passing through theory. Now, Adorno was thinking of the American society he had left fourteen years earlier when he described the personality type he called *the joiner*. For Adorno, the joiner was the antithesis of what Lenin saw in the merging of theory and praxis. It is the blind enthusiasm of those who always ask ‘what is to be done’? And I’ve said before, that to even ask that question displays a kind of privilege. And here it is important to note that Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason was not the using the term practical in the same way it is used today. Adorno says, the degenerate definition today of *practical* is one that is used, usually, to describe a person who can tackle problems and solve them in some useful manner. It is a kind of cleverness. So while Kant saw practical reason as superior to theoretical reason, he did not see practice issuing from anything other than theory. But Adorno’s point in his introduction to these lectures was that the societal system of domination has narrowed action, narrowed the possibility for practice, and hence theory itself, thinking, is harder and knowing what we should do very much harder even while impatience is layered over all of this due to the narrowing. The practical is ever more uncertain.

Scott Lyall

On the other hand, theory that bears no relation to action will succumb to a kind of irrelevant intellectual game, dead scholarship, and this is true in art as well (as Adorno mentions). Morality is not ethics, and Adorno called ethics the bad conscience of morality,

“…the ethos is a daemon, or we might it call it the destiny, of man — points in the same direction. In other words to reduce the problem of morality to ethics is to perform a sort of conjuring trick by means of which the decisive problem of moral philosophy, namely the relation of the individual to the general, is made to disappear.”

Adorno

Now, I want to mention here that the top quote of this posting, by Raymond Chandler, was used by Frederic Jameson is a book that is forthcoming, on the works of Chandler. And this is actually linked, at least in my mind, to Adorno’s late lectures on moral philosophy. Now, one of the intellectual trends, it seems to me, that followed on the spike in marketing and advertising, in media and the Bernays epoch of post WW2 America, was one that ended up with a new kind of idea of individualism. Adorno even uses the term ‘realize onself’. One branch of this was the new age pulp mysticisms of the 60s; everything from EST to Scientology to Esalen. And from there to the selling of eastern religious practice to Westerners. Now there are and were huge discrepencies in seriousness among the devotees of Buddhism and Hinduism, but the point was more that all this ended up serving as a kind of backdrop for self realization. And 12 Step programs are another variant of this, and really, it is now deeply embedded in American culture, and offhand comments such as ‘working on oneself’ are quite common. The human being is in the western imaginary today a kind of automobile engine that needs work, mechanical improvements, and maybe turbo charging and fuel injection. And one other branch involved was the idea that self realization, or that process, was somehow working in harmony with society. That adapting to difficulties was a sign of maturity. But behind that was the idea that culture, and society, were somehow NOT in opposition to the moral. Adorno concludes his first lecture by saying it is better to retain the concept of morality, even critically, then to submit to the sentimentalized concept of ethics.

Ljubomir Popvic

Now, the idea of morality, though, in its origin DOES align with an idea of harmony between the individual and the community. The moral life of the individual is ideally one that is consonant with public notions of right and wrong. That is the whole basis of custom and law. In an ideal world anyway. The problem today is that the state, the evolved form of community, has taken on excessive and abnormal power. But it is at this point that language enters this discussion. And Adorno goes to great lengths to analyse how the concept of morality is no longer identical with its original meaning. In fact the idea of moral and immoral are now primarily sexual in connotation. Now Adorno mentions Buchner’s play Woyzeck — in which there is a scene between the Captain and Woyzek where the latter is rebuked for having an illegitimate child. The Captain however also asserts that Woyzeck is a *good man*. The point of the scene in fact is the utter contradiction and irrationality of conventional morality in such a context. I mention this because it is the capsule explanation for why there is today a reluctance to even use the word *moral*. And Adorno’s point in his lecture is that this reluctance has led to an over reliance on the term and idea *ethics*. And ethics today means that one should live in accord with their own nature. Whatever that is (and this accounts for, I think, the marketing of new diets or exercise programs…it is always a REdiscovered secret. Cavemen ate this way or did push ups like this, or this was the dietary regime of Pharaohs, and they were all skinny …etc etc.). Self realization again. The ideal being strived for in all self help programs is astoundingly murky. Adorno sees the rise of ethics coming out of the Existentialist movement. I’m not sure this is completely correct, but it is true that the this notion of realizing one’s true nature is pure sophistry. There is no nature from which we have somehow wandered. But it is consistent with a focus on personality and ideas of identity. And behind all of it is the belief in individuality.

Theophilus Brown

We just need to be ourselves. And that following on this realized ideal of human nature are constructed all sorts of ideas about ethical behavior (and much else). Now, allow me to quote Adorno here…

“…in all likelihood nothing is more degenerate than the kind of ethics or morality that survives in the shape of collective ideas even after the World Spirit has ceased to inhabit them — to use Hegelian expression as a kind of shorthand. Once the state of human consciousness and the state of social forces of production have abandoned these collective ideas, these ideas acquire repressive and violent qualities.”

So it is not the decline of morals that is the problem but rather the compulsive imposition of outworn customs and their contradictory relationship with morality. And one more quote here from Adorno…

“We can say that the horrors perpetrated by Fascism are in great measure nothing more than the extension of popular customs that have taken on these irrational and violent features precisely because they have become divorced from reason — and it this that forces us into theoretical reflections.”

Raymond Chandler

Toward the end of his life, Adorno wrote Horkheimer that he had hoped their book (Dialectic of Enlightenment) would help prevent the young from succumbing to a blind practice and collective narcissism that was the aim of the administered society. But before returning to the lectures on moral philosophy, I want to touch on Jameson’s remarks on Chandler. And I started to think a bit about Chandler this week, as it happens, because of a social media thread that was asking people for their top ten films. Such lists are absurd, of course, but it served to make me think of why, as someone later asked me, I so rarely mentioned Tarkovsky. And it is true, I harbor a strange suspicion about Tarkovsky and had never bothered to investigate why that was. But it’s actually related to this issues raised in this post. And it has to do with something deep and elusive in his films, something that seems detached from history even as history is often raised as a subject or theme. I said to someone else that Tarkovsky felt bourgeois to me. I am not sure I can fully defend that, or even want to try, but I feel it. I feel it in some mimetic almost biological way when I watch his films. And it’s not that I don’t admire much of his work, or at least his skill. But then someone else said that Tarkovsky lacked an awareness of the vulgarity of film. And this reminded me of Adorno talking about the faint echo of the cafe fiddler in Schoenberg’s music. Film’s origins in amusement parks and seaside resorts linger throughout the history of the medium. And for various reasons I think the most purely abstract non commercial film is somehow the least successful. The Gene Youngblood school of avant garde film. And that is not fair, I know, but still — there is something inherent in film, a social quality very different from theatre. For theatre is always a ritual. And film is not. And TV even less. And yet, film for better or worse is inextricably linked with the social. In fact film now IS the social.

“For Chandler thought of himself primarily as a stylist, and it was his distance from the American language that gave him the chance to use it as he did. In that respect his situation was not unlike that of Nabokov: the writer of an adopted language is already a kind of stylist by force of circumstance. Language can never again be unselfconscious for him; words can never again be unproblematical. The naive and unreflective attitude towards literary expression is henceforth proscribed, and he feels in his language a kind of material density and resistance: even those clichés and commonplaces which for the native speaker are not really words at all, but instant communication, take on outlandish resonance in his mouth, are used between quotation marks, as you would delicately expose some interesting specimen: his sentences are collages of heterogeneous materials, of odd linguistic scraps, figures of speech, colloquialisms, place names and local sayings, all laboriously pasted together in an illusion of continuous discourse.”

Frederic Jameson

Maurice Henry

There is a curious relationship that language (and more, dialogue) has with film. Chandler was a great screenwriter, but he is something of an exception for novelists. But there is a connection here to Adorno’s issues on moral philosophy, Tarkovsky’s stealth bourgeois expression, and Chandler’s narratives. I have written earlier on the late lectures and I said, in a paraphrase, that right living cannot exist in a wrong society. The society of domination makes life impossible to get right. Which is the flippant way of putting this. But this relates also to how people lose a sense of critical awareness (or to be flippant again, their bullshit meter goes on the fritz). The current debate about Assad and Syria is a case in point. Using sources such as the United Nations suggests your critical faculties are broken, or at least damaged. And it also suggests, more importantly, that you, the white Western critic, is unaware of not being in a position to make such valuations. You do not know what is best for others. They, the people of the global south, for that is what we are talking about, know, or at least have the right to make their own choices. And this is clear when one sees Chavez’ embrace of Assad from a number of years back.

But in aesthetic terms, to keep to the example here, Tarkovsky somehow is the filmmaker version of planted propaganda stories. Now, it is difficult with Tarkovsky because he is highly skilled, and in a sense, talented (more on what that might mean below). So this is not a dismissal of Tarkovsky, but a question. That his films, finally, do not challenge the presumptions and beliefs of the bourgeoisie. Looking at Pasolini say, or Fassbinder, say, and there is an acute feeling of anti bourgeois challenge — they knew, and it is in the DNA of every frame — that the conventions of the established discourse are suspect. And as a default setting, they reject it all if it comes to that. Tarkovsky doesn’t. It is not a surprise that his ersatz mysticism appeals so greatly to undergraduate university students. In the same way, only on a higher level, that David Lynch does. Tarkovsky is infinitely more accomplished than Lynch, but the marrow of his mise en scene is non disruptive. And it’s a tad precious, too. The mystical commands a response of muted awe. And that is a danger in mysticism overall. It always defaults to a place of comfort from which to evaluate it. Now, the bullshit meter metaphor is flawed, to be accurate. For the miss-reading of social narrative, of political narrative, isn’t really about failing to sniff out the fraudulent, it is more a matter of learning to believe the fraudulent.

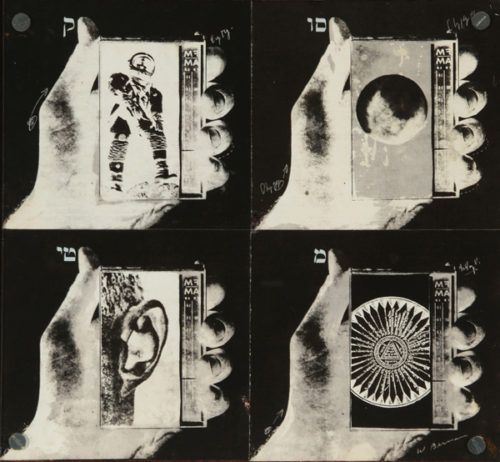

Wallace Berman

In Kant, the idea of freedom is inseparable from Reason. For in Kant, everything, really, returns to Reason. Now not to belabor this here, but this is the topic of Adorno’s third lecture from 1963. Reason is an unencumbered ability to judge, differentiate and understand. And this ability to reason is pure when it is not affected, coercively, by Nature. What is called causality, in Kant, is that relationship that mediates reason. Simply put, and this is Adorno’s example, or one of them, that the insane man who murders someone is not responsible, under the law, because he was not aware of what he was doing. Ergo, the entire question of Reason and of morality, has to do with an *I* that acts. But there is another aspect, too, worth noting without getting into a great deal of depth. And that is what Kant called the *antithetic*. And this is (transcendentally speaking) the necessary contradictions of pure reason. This is when one applies reason to that which is beyond the limits of experience. The result is what Kant called pseudo rationality. And this is that which can neither be refuted or confirmed in experience. This is a very important point in relation to what I am hoping to get at in this posting. Kant was the anti-dialectician. He refers to dialectic as the logic of illusion. For Adorno, this was the heart of the problem of moral philosophy. That the idea of right living was not an option under Capitalism.

Rosemarie Trockel

“The clearest example of why Adorno thinks that late capitalism is radically evil is the genocide of the European Jews. For Adorno, this genocide was not an accidental relapse into barbaric times, or due to the fact that modern civilisation had not fully taken root in Germany. Rather, these events mean that enlightenment culture as a whole has failed in important respects. This culture, and the modern social world that gave rise to it, are deeply implicated in the moral catastrophe of Auschwitz. They constitute the ‘objective conditions’ for its occurrence and unless they are overcome, a moral catastrophe of the same kind is possible again.”

Fabian Freyenhagen

Nostalghia (1983) Andrei Tarkovsky, dr.

As Freyenhagen puts it, ‘advanced capitalism liquidates the individual’. Adorno carefully substituted the word *right* for *good*. And this was, I suspect, because of his belief that in today’s society, the idea of good cannot even be approached. Rather we have right and wrong at best. Allow me a longer quote from Freyenhagen…

“The possibility of morally right living is blocked partly because we are caught in the guilt context of our radically evil society, but partly for further reasons. Firstly, within this guilt context we almost always get caught in ideologies, that is, we hold a set of beliefs, attitudes and preferences which are distorted in ways that benefit the established social order(and the dominant social group within it) at the expense of the satisfaction of people’s real interests. To defend our behaviour (e.g., holding on to our possessions while others face severe deprivations), we often end up implicitly defending what should be criticised, namely, late capitalism or elements thereof (e.g., its property regime). And even where we do not attempt to justify our way of life, we tend to fall prey to ideological distortions, so that we accept social arrangements as they are, instead of changing them as we should (this is true even of those who are most disadvantaged by these arrangements).Thus, either by endorsing or by unreflectively accepting distorted truths or half-truths, we entrench the social status quo and fail to do what we should do.”

The contradictions of reason, then, under a system that abolishes what it claims to promote (freedom and individuality) are impossible to reconcile or resolve. For Adorno, Capitalism is that which was occluded Nature, in a sense. Man cannot *live*, even wrongly, let alone rightly, because all options are wrong, and society has become that which separates man from Nature. And this retreat of Nature (in a very wide sense) is one of the primary factors in an erosion of Reason. So, contra Kant, the argument Adorno makes for the impossibility of right living has to do with society, and that this society is there as a way to subvert Nature, both external and internal.

Yosuke Tokeda

Adorno feared, rightly I think, that questions of what to do tended to suffer often by being turned into their opposite. That inadequate understanding (insufficient reason) led to counter productive actions. Now, I’m not going to follow this line of argument here, because I want to, instead, focus on how art and culture are affected, and how this produces (today) such extraordinarily regressive notions of both. So, in one way it is perhaps counter productive to dissect Tarkovsky in this way because there is a profound gap between Star Trek and Stalker. But the dissection does serve to try to understand what culture means. And in what way the idea of narration is being lost, as both an idea and in practical terms.

“Suppose that I am going to recite a psalm that I know. Before I begin my faculty of expectation is engaged [tenditur] by the whole of it. But once I have begun, as much of the psalm as I have removed from the province of expectation and relegated to the past now engages [tenditur] my memory, and the scope of the action

[actionis] which I am performing is divided [distenditur] between the two faculties of memory and expectation, the one looking back to the part which I have already recited, the other looking forward to the part which I have still to recite. But my faculty of attention [attentio] is present all the while, and through it passes [traicitur] what was the future in the process of becoming the past. As the process continues [agitur et agitur], the province of memory is extended in proportion as that of expectation is reduced, until the whole of my expectation is absorbed. This happens when I have finished my recitation and it has all passed into the province of memory. And this which takes place in the whole Psalm, the same takes place in each several portion of it, and each several syllable; the same holds in that longer action, whereof this Psalm may be part; the same holds in the whole life of man, whereof all the actions of man are parts; the same holds through the whole age of the sons of men, whereof all the lives of men are parts.”

Augustine

Book 11, Confessions.

Adriana Varejao

Aristotle said that narration was the mimesis of an action. Now this noted paragraph from Augustine (one Husserl and Merleau Ponty and others mention frequently) is important in understanding what theatre does, and in a sense what film implies. For I continue to return to the idea of memorization in theatre; whenever I reflect on theatre these days I am struck by the significance of recited memorized text — on stage. The actor is not a character until after he engages with the idea of expectation and memory. And expectation is not, I don’t think, the same as anticipation (more on that in a second). The point here is that in film memorization for the actor is mitigated — there is simply much less of it, and in fact, several branches of filmmaking did away with memorization altogether. Wender’s Paris Texas is mostly a snooze (notwithstanding the great Harry Dean Stanton) because most of it is improvised. Shepard wrote one scene (at the peep show), and it is the best scene in the film and one of the great scenes in film history. Why? Because it is about the text, about a memorized text first and a scene in which expectation is gradually swallowed by memory — for the actor, and the audience is then witness to the absorbing of expectation.

And yet why is it that Shakespeare so infrequently translates well to film? I suspect it has to do with the acute force of memory in live Shakespeare (this is where an entire post could be devoted to Francis Yates and the Globe Theatre). The linkage here with moral philosophy, as Adorno examines it, in his uniquely Kantian light, is that the administered society has wounded interior life, and that expectations for ethical behavior (let alone moral purity) are impossible — and this guilt complex, a collective guilt, impedes, on the cultural level, expansive narration. And as Adorno put it, the assumption of moral certainty is itself immoral.

Merchant of Four Seasons (1971) Rainer Werner Fassbinder, dr.

Raymond Geuss has a footnote in his book on Ethics, in a chapter in fact on Adorno.

“Alexander Kluge tells the story of a Russian émigré to Berlin during the 1920s named Leschtschenko who opened a studio for producing Russian versions of American (silent) films for distribution in the Soviet Union and American versions of Russian (silent) films for distribution in the United States. One major difficulty was that all the American films had happy endings that would have been considered silly and superficial in Russia, while the Russian films had melancholy endings that were not appealing in the United States. My suggestion is that this difference is no more than a difference of national temperament, i.e., the sediment of particular differential historical experiences, not matters which one group or the other “got right.” Optimism and pessimism are matters for the psychoanalyst and historian, not the philosopher (or theologian). The Russian émigré thus had the task of filming new “happy endings” for the Russian exports to the United States and new “unhappy endings” for the U.S. exports to Russia. This was a slightly tricky task, since the original actors were never available. How then could one film a convincing new final scene? He had to become very adept at using various dodges, illusions, and suggestive techniques. Fortunately, Leschtschenko discovered, by the last scene a film has built up a certain momentum, which will carry audiences along and cause them to “supplement” what they actually see in the direction of the expected coherence (“Der Zuschauer verzeiht. Er geht mit. Er ergänzt,”). In fact, the audience would do almost anything rather than find their expectations (for a happy ending or a sad ending, as the case may be) disappointed. To beforced to confront an inappropriate ending, however, is something an audience would never forgive.”

Chandler and Billy Wilder, during filming of Cain’s Double Indemnity.

Now, the case of Chandler is of interest, I think, for two reasons here. One is that he became the exemplar of a detective fiction, and that means that the narrative revolves around a murder. And secondly, he was describing an America now vanished. And it is the particulars of that vanishing that seem important. Chandler described a moral universe of absolute institutional corruption. For Chandler, the Private Eye was a kind of Knight Errant, venturing out in the search of truth. And he failed a good deal before he succeeded, and his success was usually highly mediated. Early European crime novels usually featured a policeman as the protagonist. This changed in the U.S. because of Hammett and Chandler, mostly, who both sensed the overriding atmosphere of paranoia in the country. And this began in that period between the wars. Jameson notes that…

“On the one hand those parts of the American scene which are as impersonal and seedy as public waiting rooms: run-down office buildings, the elevator with the spittoon and the elevator man sitting on a stool beside it; dingy office interiors, Marlowe’s own in particular, seen at all hours of the clock, at those times when we have forgotten that offices exist, in the late evening, when the other offices are dark, in the early morning before the traffic begins; police stations; hotel rooms and lobbies, with the then characteristic potted palms and overstuffed armchairs; rooming houses with managers who work illegal lines of business on the side. All these places are characterized by belonging to the mass, collective side of our society: places occupied by faceless people, who leave no stamp of their personality behind them, in short, the dimension of the interchangeable, the inauthentic.”

File on Thelma Jordan (1950). Robert Siodmak, dr.

Following the sixties, the detective returned into the fold of the police. And the disequilibrium that was the perspective of Sam Spade or Marlowe is increasingly obscured in the post Vietnam crime narratives. The crime itself looses resonance.

“Our social context engenders the opposite of identification-based solidarity, namely, bourgeois coldness. It is this coldness–the ability to stand back and look on

unaffected in the face of misery–which made Auschwitz possible.”

Fabian Freyenhagen

The police detective is the avatar of bourgeois coldness today. There is additionally the insertion of technological coldness. Surveillance replaces the intuition of Phillip Marlowe or the Continental Op. But there is another aspect to Chandler, and one Jameson notes, and that is how he depicted the realm of the wealthy. For this was always a world of death and decay. And emotional deadness. Private estates with guarded entrances, long secluded driveways, and anonymous security personnel. And it is interesting how this translated to the screen in the noir films of German emigre directors. Double Indemnity for example, or Angel Face, or File on Thelma Jordan. And much of this was mined from (and often written by) the great pulp writers of the period (Cornell Woolrich, James Cain, David Goodis, and Jim Thompson). And it is probably Cain who most closely approaches the genius of Chandler and Hammett. In all these writers there is an overwhelming feeling of suspicion. And it is a world of class conflict, perhaps most importantly.

Ron Jude, photography.

“Only through imitative behavior, which for Adorno originally

goes back to an affect of loving care, do we achieve a capacity for

reason because we learn by gradually envisioning others’ intentions

to relate to their perspectives on the world. For us reality no longer

merely represents a field of challenges to which we must adapt;

rather, it becomes charged with a growing multiplicity of intentions,

wishes, and attitudes that we learn to regard as reasons in our action.

Adorno does not restrict this ability to perceive the world, as

it were, “from the inside out” to the domain of interpersonal behavior.

To the contrary, he sees our special, imitation-based capacity for

reason precisely in experiencing the adaptive goals of speechless beings,

even things, as intentions demanding rational consideration.

He is therefore convinced that any true knowledge has to retain

the original impulse of loving imitation sublimated within itself in

order to do justice to the rational structure of the world from our

perspective.”

Axel Honneth

Mister John (2013). Molloy & Lawlor dr.

Bourgoeis coldness is, then, an aspect of this reified ‘second nature’ that Adorno and Benjamin both saw as the crises of psychic life under Capitalism. Commodity exchange decenters man (Adorno) and distances, or really, imposes a process of unlearning, the early mimetic perception. And this second nature, then, carries with it a deforming of Reason itself. So, when one looks at the inability of so many commentators on culture and politics, today, to read what is rather obvious propaganda, and contradictory propaganda at that, the causes lie back with the development of exchange value itself. For this marked the beginning of this reified paralyzed and frozen second nature; intractable and alienating. Perception itself becomes imbued with calculus and self aggrandizement. There seems to be an enormous forcing of self importance for everything is graded on moving up this phantom ladder of recognition and success.

From notes of Adorno & Horkheimer…

“In Germany, fascism won the day with a crassly xenophobic, collectivist

ideology which was hostile to culture. Now that it is laying the

world waste, the nations must fight against it; there is no other way

out. But when all is over there is nothing to prove that a spirit of

freedom will spread across Europe; its nations may become just as

xenophobic, pseudo-collectivistic, and hostile to culture as fascism

once was when they had to fight against it. The downfall of fascism

will not necessarily lead to a movement of the avalanche.”

Aaron Bobrow

The faux radical critiques that employ ‘totalitarian’ as a term, for example, miss the fact that all capitalism is, really, totalitarian. But such critiques allow space for the employment of regressive racist terminology (thugs, regimes, strongmen, et al). For the author of such critiques has already been distanced from their own nature. This is the legacy of a reified character. And this is the instrumental logic of a reified vision of the world. For in that reified worldview there is no space for compassion — unless of course it is the designer compassion that yields self advancement for the subject. The legacy of suspicion found in Chandler (and the other Black Mask writers) haunts contemporary emotions, I think. What was once a suspicion of authority and institutions has been re-directed toward self. And this is a kind of doubt, and it erodes the potential for solidarity. It erodes trust, as well. And in terms of reading narratives, both cultural and political, this has meant that the kind of mysticism of a Tarkovsky is easier to digest than the anger and self analysis of a Fassbinder or Pasolini. And if we extend this idea to Antonioni or Rossellini, there is something of the anti-mystical in their poetics. The dreamlike mise en scene of Tarkovsky is legitimate because of his deeply sensitive eye for human frailty, and that is admirable, but it is also too seductive in its intentions. Antonioni’s L’Aventura is stripped down to remove the fantastical, even if one might accuse him of switching seductions. If Antonioni had a failing it was his own infatuation with the beauty of Monica Vitti. One of the things I found so remarkable about the little seen film Mister John (Molloy and Lawlor, 2013) was that it worked from a strategy of elimination. The story is so minimal, and so much is simply interior that the viewer is forced to *read* the entirety of the film, really, in the face of Aiden Gillen. And it helps, of course, to have an actor with as much internal life as Gillen. The human face is, of course, the currency, always, of Pasolini. And in a way it is of Fassbinder, too.

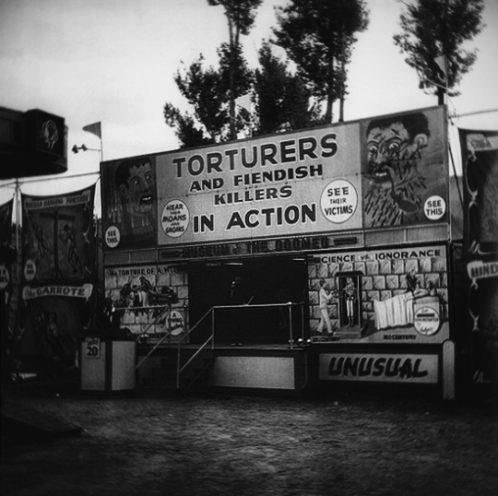

Photographer unknown

The political opinions, today, of self identified leftists feel, often, to be arrived at as the result of a certain unconscious calculation based on an economic risk management study. It was Sartre who said the attempt to be sincere is always taken in bad faith. In terms of theatre and film, then, sincerity is impossible per se. What *is* possible is the experience of expectation being absorbed, and then the implications of that. This opens up another large discussion, which is beyond this posting, and that is art that represents war crimes or genocide. For it is the return of suffering to the comfort of the lounge and theatre. And hence there lingers a quality of pleasure in it. And this is why form matters more than theme or message. One can, of course, have both, but such examples are pretty rare. And I’m not sure I’m convinced they work ultimately. In one way this is why Adorno favored Beckett because such crimes are unthinkable. Unspeakable. The role for art is never to propagandize, but to strip away illusion and reveal something of the empty pathologies of reified individuality, and societal sadism.

I’ve been reading your journal alongside other ‘alt.’ media the past few years. Like most Millennials, I’m sickened by the mainstream media, and I’m desperate for any semblance of ‘truth’ within our news media.

I noticed in one previous entry, you had critiqued Alex Jones, which I find fascinating, because he says some lines that are strikingly similar to your lines of thinking. For example, you mention how the ‘psyche’ is effectively beginning to become inaccessible. In a recent show, Alex Jones erupted in his usual theatrics, but he yelled “They’re purposely going to erase the psyche to destroy us!”

Regarding Clinton’s call-out of ‘alt-right'(which they don’t even label themselves as), Alex Jones firstly refuted her lies, but his main reply to her was, fascinatingly, ‘Get behind me, Satan.’

He ended that video with “I don’t fear those that kill the flesh, but those that kill the soul.”

Of course, the whole issue of her health arose from Info Wars, but it began with Alex Jones requesting to watch videos of her effectively seizing in public, and his first question was “Is she demon-possessed?” (pertinent question, on some level).

What do you make of this debacle of Clinton desiring to censor the ‘alt-right’, considering some of those recent lines from Alex Jones?

Thanks so much for your insight, you’re highly erudite and I hope to be as such some day.

@ K.C.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1vb6K3ldilo

Not quite sure how that answered my question…

I find it interesting that there appears to be a synchronicity across political spectrums, amongst observant minds, that Clinton is ‘demonic’.

As Assange recently argued, she’ll become a propped-up ‘demon’ upon election, as she’s been mindlessly ‘demonizes’ the Russians.

But that’s simply projection on her part.

The body count following the Clintons? Were these people not ‘demonized’ and scapegoated?

Is it not a prime case for the ‘death instinct’?

Is that not the stage at which our Civilization’s at?

Even Alex Jones, ‘amazed’ by the Communists, sees it on some level.

Is it not interesting?