Liza Lou

“Benjamin sees Germany – then in the midst of the Weimar period, before the Nazis took power – as caught up in a kind of regressive collectivism born of capitalism.”

Andrew Robinson

“In a sense, the pervasiveness of neoliberal ways of talking has the effect of turning people into calculators of advantages. There is this book, Everything I learned about love I learned in business school, and it’s about ‘cutting your losses’, about having a ‘mission statement’, about ‘measuring performance’… In a curious way, in terms of classical political economy, Hobbes thought we needed a state to restrain our appetites, and it may be that the neoliberal state has so colonized our way of decision-making (stimulating our appetites), that the neoliberal state has in fact created the human actor that now does have to be restrained by the state.”

James Scott

“Modern science makes us understand the true character of the machine, of rationalization and of standardisation. All of that leads to one thing only: the economy. Economy attempts (is) the symmetricalisation of forces.”

Asger Jorn

Will Self recently wrote on the new Tate Modern extension, due to soon open.

“Public galleries have often accepted artworks as donations, but in the 1990s they began accepting such donations from the artists themselves, and then putting them on display. This represented a flagrant disregard for curatorial standards, and registered the exact point at which the hyper-rich artists and their still more moneyed dealers began to call the tune – henceforth the “crap” silting up public galleries would be deposited there by the ebb and flow of finance rather taste. But really, as I said at the outset, I blame Marcel Duchamp. His four signature works of the 20th century: Nude Descending a Staircase No 2 (1912), Fountain (1917), The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915-23), and La boîte-en-valise (1941), represent the response of an artistic genius to the problem of the artwork in an age of mechanical reproduction. What Duchamp – unlike Perry – understood, is that the gallery is fundamentally otiose once easel paintings and sculptures cease to be meaningfully unique objects: because if they’re capable of reproduction, what need is there for a unique place, time and space in which to display them?

The new Tate Modern will thus be not an art gallery per se, but a sort of life-size model of what an art gallery might be should our culture have need of one. Since it doesn’t, but rather has a requirement for visitor attractions that reify the ever‑widening gulf between haves and have-nots, I’m absolutely certain it will prove an outrageous success.”

Now, it’s not that this isn’t true, exactly. It’s more that it betrays something of the poverty of contemporary culture altogether that such an essay is even necessary. This was the week of the Nice attacks, and also the aborted *coup* (sic) in Turkey. Andrew Robinson’s article on Walter Benjamin ( https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/walter-benjamin-fascism-crisis/ ) touches on an aspect of how degraded life has become. The brutal effects of poverty are obvious, and the acceptance of this poverty, of the very existence of poverty, speaks to a loss of empathy. And this is part of a fabric of generalized but unarticulated psychic suffering in today’s society.

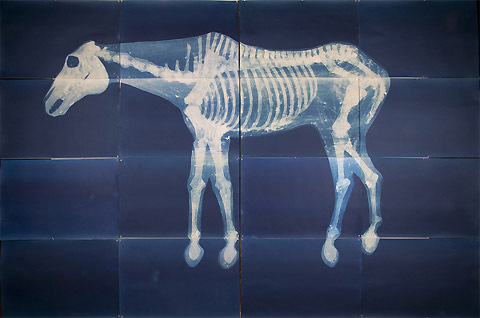

Carrie Witherell, cynotype.

Let me quote Robinson (on Benjamin) again…

“To outsiders, the national temperament seems to have become barbaric and violent in an incomprehensible way. According to Benjamin, this appearance – invisible to those within the process – occurs because people are wholly subordinated, to ‘circumstances, squalor and stupidity’, to collective forces. The sense of any right to live individually has disappeared. People also develop a ‘frenetic hatred of the life of the mind’.”

This hatred of the mind, of course, is most acutely seen in cultural affairs. And those cultural affairs, more than ever, bleed over into political issues. For politics today has become a weird disfigured form of theatre. Now Robinson focuses a lot on ecological questions, and while I don’t disagree, per se, it’s also something I haven’t quite found the right language or conceptual form to discuss. That is just my failing, probably. But I find the majority of environmental discussions I have tend toward very simplistic and even reactionary constructs. It’s why I so dislike Green parties. But let me return first to this psychic suffering. The bourgeoisie, for Benjamin, in their apparent victory have proven incapable of sustaining their consciousness — meaning that they lose even when they win. And there is a new desperation in the bourgeois class today. A frantic and distressed kind of mental pathology. The obvious expressions of this are found in a growing hostility to the poor, but also in an a kind of generalized rudeness and lack of civility. Benjamin noted this during the Weimar years, and it is echoed in the contemporary West today. The differences between the pre-Hitler period in Germany and those in the U.S. today is that these tensions are now given labels and conceptual context, even if utterly fictional. The bourgeois class announces its own virtues constantly. And this is seen in popular culture. Hollywood is a self congratulation machine. When Robinson compares Britain today with 1930’s Germany he sees many similarities, and all tied to Capitalism and private economic interests. The overriding quality is (per Robinson) a regressive collectivism. I have described this as the penchant for agreement. Consensus is one of the stable templates for orientation. Consensus is the psychological refuge of the educated class today.

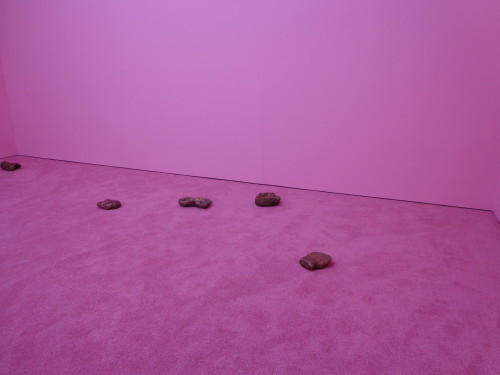

He Xiangyu

This collectivism is also a protection against actual thought. The contemporary Westerner, by and large, avoids thinking. As funny as that sounds, I think it’s quite literally true. And this brings me back to aesthetics, a crucial topic for Benjamin and Adorno, both. Robinson writes ; “Fascism is thus partly a product of spectacle. Benjamin relates it to the spectacular nature of commodities, which are transformed in their presence from simple objects to spectacle or phantasmagoria.”And I wrote a few posts back about Futurism, and again it comes up in Robinson’s essay. For fascism inevitably leads to war. And today, there is a dire sense of the aestheticizing of politics, but also of a regressive aesthetics. The Futurists were fascists, but at least they were decent artists. And this is one of the qualities I take away from the current climate of the West, a disingenuous but intractable stupidity of perception and thinking. And even people I consider quite intelligent seem caught up in it. And partly the difference has to do with the advances in technology. Marinetti loved machines, but imagine his response to the world of computer imagery and digital technology. By and large the uses of technology today, certainly aesthetically, are highly regressive. And it is a call for agreement in the collective. And this is where the *Green* ethos is worth noting. Anyone even vaguely questioning climate change, for example, is subjected to intense stigmatizing and shaming. The environmental issues of the day are kept at a certain distance because their uses for the lynch mob mentality are too great for people to really explore the Capitalist underpinnings of the crisis. And which are real and which are just alarmist click bait.

“The authors of war literature, according to Benjamin, are expressing a particular class perspective. Many of them are specialist soldiers, commandos and engineers – the military equivalent of the managerial class. The ideology of endless war, of a magical power of war, is implicitly portrayed as a kind of class ideology of the elite soldier.

These former soldiers were to become the social basis for fascism, as Benjamin recognised. Many of them graduated from the army to the Freikorps to the Nazi Stormtroopers. Today, this underlines the importance of demobilising and reintegrating former soldiers – many of them economically disadvantaged and war-traumatised – in the aftermath of conflicts. It also underlines the persisting importance of militarised masculinity in the securitisation of civilian spaces.”

Andrew Robinson

Margaret Evangeline

The above quote is interesting because it probably doesn’t go far enough. The managerial class have been made *heroic* by mass media and popular culture. The professional techno soldier or assassin or cop are usually depicted as either highly skilled in digital technology or they employ such a person as a sort of sidekick. Hollywood has spent a lot of time trying to make typing on a keyboard sexy. It isn’t ever successful and somewhere in the consciousness of today’s audience, they know this and they recoil, instinctively almost, from such depictions. The problem, of course, is that the compensatory code is physical domination. The narratives of securitization are everywhere. And yet they always unravel at a certain point because there is an equal competing trope of constant insecurity. And partly this explains the popularity of fantasy and science fiction. When Robinson suggests a dichotomy in fascist cultural expression, in which they become ever more divorced from political economy; I think he is right. And this leads back to this quality of surreal stupidity I find in (mostly U.S.) contemporary consciousness. Boris Johnson and Donald Trump are two of the more obvious avatars of theatrical stupidity. They are mirrored by the managerial discipline (fictional, mind you) of a Hillary Clinton or David Cameron. Clinton is a special case, in a way, however. For she is incapable of really hiding her reptilian soul. I suspect Trump was employed as a foil and only because Hillary is such a wretched candidate, does he stand any chance (Think Mel Brooks’ The Producers). The rise of risk management is now one of the constant narrative themes in today’s culture.

Daphne Rocou, photography.

People tend not to engage with art or culture on any level that is separate from the economic. And the habits of consensus are really the offspring of tacit subordination. Looking at artwork as quantity — quantity means commodity, and that means there will an atrophying of discernment.

“The acting that comes of civility will be of less interest to us in what follows

than the acting that has been imposed throughout history on the vast majority

of people. I mean the public performance required of those subject to elaborate

and systematic forms of social subordination: the worker to the boss, the

tenant or sharecropper to the landlord, the serf to the lord, the slave to the

master, the untouchable to the Brahmin, a member of a subject race to one of

the dominant race. With rare, but significant, exceptions the public performance

of the subordinate will, out of prudence, fear, and the desire to curry

favor, be shaped to appeal to the expectations of the powerful.”

James Scott

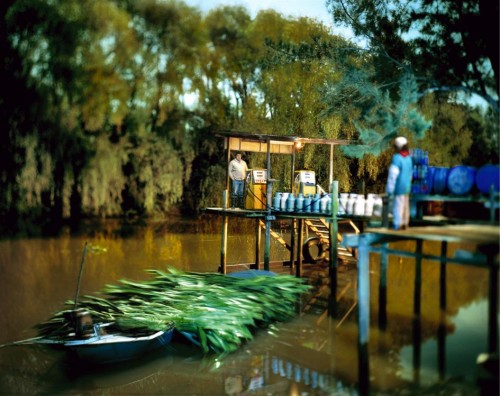

Alejandro Chaskielberg, photography.

Contemporary culture, at least if I am speaking of the bourgeoisie, has without realizing it consciously, come to their public performance of self with the idea of pleasing the wealthy. The public likes what prestige media outlets tell them to like (and the younger public likes what the *hip* media tells them to like which is a youth version of the same thing). Now its not entirely that simple, of course. And one reason it is not so simple is that in the U.S. anyway there is huge anti-intellectualism at work. It has always been there in the U.S. but not in the way it exists today. Once a TV show, for example, becomes popular, it enters the public discourse — Game of Thrones or Breaking Bad are mined for references and used to *explain* other things, even Nature. The dominant ideology, in other words, becomes imprinted on people who adjust their behavior and beliefs to conform to it. The two party ritual of presidential elections is one now believed to be inevitable and even natural. And hence, those involved in this ritual, who have bought in, as it were, becomes hugely defensive of those who question the legitimacy of said ritual. The entire lesser evilism idea is really one that enforces conformity. Evil is inevitable, so it is irresponsible (!) to try to escape it.

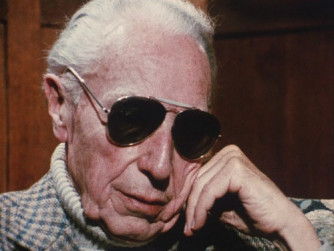

Douglas Sirk

Things like the militarizing of the culture, aesthetically speaking, has meant that there is now an expectation for state violence. It is natural. Never ending war is part of the landscape. For young men, in particular, the heroic ideal is now default set at soldier or cop. And when it’s not, when say an athlete or a politician is presented as heroic, the language is full of military metaphors and vocabulary. And as I said last posting, the urban landscape is now described as a war zone. A place in need of pacification. And there is an interesting connection between this surplus fantasy narrative today and the way it is used to develop social criticism. The fact that TV and film are experienced as more real than life is not surprising because in a sense it IS more real for most people. The standardized dullness of daily life, the repetitive nature of labor and the sense of abjection are escaped in the fantasy locals of popular culture. But to escape daily life means, eventually, that one does not SEE daily life. And does NOT hear it. I once taught with Murray Mednick, a theatre workshop, and we discussed maybe compiling a book on our workshop teachings. And the title was to be “Failure to Listen”. Audiences today for theatre certainly has lost the ability to listen. Almost completely, in fact. Film and TV are scored in ways that obscure the fact that stories make no sense. A recent western was released with Woody Harrelson, called Duel. I watched half of it and stopped. I had no idea of the story. It wasn’t only that it made no sense, it was not even there as a story. There was no story, at all. In its place was a lot of familiar cues, taken from other films and TV, and a rhythm that was familiar. Editing and music (and actors) had been seen and heard before, so presumably the audience was pacified. Much as war zones are pacified.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Edward Said, shortly before his death, in an interview on the BBC that the one outstanding quality of life today was its unreality. And that is what I think I am getting at. And while there is certainly a lot of good art out there (surprisingly perhaps), there is less and less of an audience for it. Marque museums are filled, but that does not mean there is an informed audience at all. In fact there is a constant complaint that 90% of today’s art is crap. Is junk. And while there IS a lot of very mediocre art, that position is far too easy, and more importantly, smacks of this faux populist anti intellectualism. The problem is that the very tendencies that Benjamin saw in Weimar, Germany are ones that have resurfaced — only worse. Those who insist on Hillary saving us from Trump, as a current example, are people who cannot read narrative or dissect performance. For this is not a political opinion, its a cultural one. I have countless debates, often with very smart people, and I sense there is a failure not in their analytic skills, but in a core collapse of cultural learning.

Kenneth Burke, in his introduction to A Grammar of Motives…wrote…

“Our term, “Agent,” for instance, is a general heading that might, in a given case, require further subdivision, as an agent might have his act modified (hence partly motivated) by friends (co-agents) or enemies(counter-agents). Again, under “Agent” one could place any personal properties that are assigned a motivational value, such as “ideas,” “the will,” “fear,” “malice,” “intuition; “the creative imagination.” A portrait painter may treat the body as a property of the agent (an expression of personality), whereas materialistic medicine would treat it as “scenic,” a purely “objective material”; and from another point of view it could be classed as an agency, a means by which one gets reports o£ the world at large. Machines are obviously instruments (that is, Agencies); yet in their vast accumulation they constitute the industrial scene, with its own peculiar set of motivational properties. War may be treated as au Agency, insofar as it is a means to an end; as a collective Act, subdivisible into many individual acts; as a Purpose, in schemes proclaiming a cult of war. For the man inducted into the army, war is a Scene, a situation that motivates the nature of his,training; and in mythologies war is an Agent, or perhaps better a super-agent, in the figure of the war god. We may think of voting as an act, and of the voter as an agent; yet votes and voters both are hardly other than a politician’s medium or agency; or from another point of view, they are a part of his scene. And insofar as a vote is cast without adequate knowledge of its consequences, one might even question whether it should be classed as an activity at all; one might rather cal1 it passive, or perhaps sheer motion (what the behaviorists would call a Response to a Stimulus).”

Victor Racatau

This is actually not so very far from James Scott’s notion of ‘hidden transcripts’. It even relates to Ervin Goffman’s ideas on how we present ourselves in daily life. And I think it worth going all the way back to Swift to see the potential for complexity in narrative. For the voyage to the floating island of Laputa (Gulliver’s Travels) operates in several registers at once. It is both a satire of the Royal Society, and the ubiquitous Newtonian science of the day, but also to a manner of willful blindness in those self appointed priests of learning. The blindness, in particular, to the suffering of those below. The clarity of Swift’s prose is a good part of the actual meaning of his satire. There is no longer the capacity to write as Swift wrote. For with Swift, the satire is only meaningful because of the basic seriousness of the sensibility. And this particular kind of serious is one marked by an absence of self congratulation. Swift felt deeply the darkness of a society awash in self praise. Today a Swift would be called *negative*. Seriousness itself is suspect. How often do politicians smile today; and not just smile but smile with mouths open, teeth bared, in this exaggerated cartoon of near hysteria.

Burke quotes Marx on justice. Its connection to the economic conditions of society (and the cultural development that comes with them). Today, as Burke noted, justice is increasingly a product of personality. A property of agency.

Leah Sobsey, photography.

“According to the Marxist calculus, insofar as the world becomes industrialized under capitalism, workers everywhere share the same social motives, since they all have the “factory situation” in common. This is the scene that shapes the workers’ acts, and their nature as agents, in conformity with it. Stated in terms of money (the capitalist god, from which are derived men’s freedom and their necessity) the motive common to the workers is “wage slavery.” It is universal as a motive whenever the means o£ production are private property, with wages and taxes being paid in symbols rather than in kind. But it divides the over-all capitalist motive into two broad economic classifications, h e possessors and the dispossessed, with each status analyzable as a different substance, or contrasting bundle of motives.

Translated dramatistically: the sheer work in a factory would not be an act. It would be little more than motion. And this motion becomes actus only when the workers’ status is understood in terms of socialist organization. This act is o£ revolutionary import since the sheer ownership Af the factories is a state: hence the property relation becomes increasingly passive, while the proletarian relation becomes increasingly active. “

Kenneth Burke

Erving Goffman

Erving Goffman wrote The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life in 1959. Over half a century ago. The date is relevant because the book feels almost shockingly contemporary. That said, there are disquieting shifts in how his model for human performance would operate today. The model of the theatre is one that goes back, at least, to 4th century Greece. And the durability of this form is found in the doubling aspect, the living metaphorical component of the stage and the actor. Our unconscious is likely a theatre set in a certain sense. The shifts in this theatre of the mind, however, have to do with the loss of historical knowledge. Great playwrights always sensed the past chasing them. And this is no longer true. I have written before that theatre is almost dead, today. Quick, name a significant playwright currently being produced (for there are, no doubt, great writers for theatre, but they aren’t being produced). But this lack of great theatre has to do with both electronic media, and more, perhaps much more, to do with a society that cannot, by and large, locate their own allegorical lives in the narratives they see or read. Benjamin called Kafka the last storyteller. And while they may not be strictly true, the point is true. The theatre has turned away from work that dislocates the viewer and rather favors wortk that reproduces or mirrors a reductive version of daily life. It is not really a mirror, however. It is a fun house mirror at best. American theatre is now in the hands of that same liberal class that is wringing its hands in fear of Donald Trump. It is in the hands of those who see relevance ONLY in identity issues or vague kitsch neo-allegories of the little guy fighting the big state. These latter pieces are particularly pernicious. Now, when Goffman wrote of our daily performances, he was talking about the workplace, or public spaces that forced a certain degree of interaction.

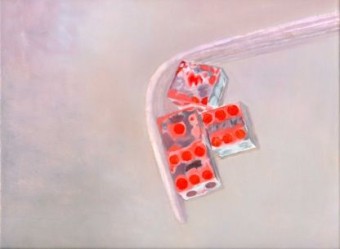

Imitation of Life (1959), Douglas Sirk, dr.

The Dictionary of Critical Social Science defines civil inattention (per Goffman) as…

“A norm of mass market societies which requires one carefully avoid interaction with other’s physically present. If the others are part of a social base, then civility would be required; if others are nonpersons, then one can be uncivilly inattentive, i.e., one can stare, push, look through, speak through or talk about others in that presence.”

Today, even close friends are often treated with a version of civil inattention. Except it is not read as such. The etiquette of cell phone texting is an entire sub topic all onto itself. It is also worth noting that sociology today has focused far more literature on the behavior of crowds, and the control thereof than it has on individual patterns of *acting* in public or semi public spaces. Goffman’s follow up book, Behavior in Public Places (which is much neglected) is less methodical and more anecdotal, and perhaps the more significant for that. And in the introduction he raises, in an offhand way, what constitutes *approval* in public interactions. And what motivates this approval. This is important, I think, because approval is less and less a decided upon action. Approval is more tacit, today. It is anything not disapproved. But is also prey to a much larger condition of withheld decisions. Now one of the things I expect to increase significantly in the near future are rules of trespass and exclusion in public spaces. Things have been trending that way for the past forty years, but spiked after 9/11 (speaking of the U.S. and western Europe). The rise in militarized policing means that western nations face a return to the really repressive regulations of medieval societies. One can expect Hollywood in the near future (it is already doing this to some degree) to stigmatize the crowd as an inherently malevolent configuration.

Asger Jorn

In Goffman’s original analysis, the actor performs his role in an effort to impart social status and social intention. He differentiates a back stage role as well, and even an off stage. So I am riffing off this model to segue into my notion of the off stage as the unconscious, then I think what has happened over the last half century is that the back stage has shrunk, and the off stage is denied. The demonizing of Freud, or at least the discrediting, is part of an overall effort by the gatekeepers of culture to convince people that they simply don’t have an unconscious. In Goffman’s book on mental institutions he cites *instrumental formal organizations* — and this now resembles public behavior in the West. In other words we live in a society structured like a mental institution. One must be seen to be engaged in activities that are acceptable to the social good. Except today nobody really could even begin to define the ‘social good’. But remember, one in four Americans takes some form of prescription anti-depressant. And I would guess that such treatment contributes to the generalized autism of the populace. Those activities prescribed by institutions for the mentally ill have no real meaning or use, but are regulations of control. The criminalizing of protest today is an example of keeping the public away from that off stage unconscious and from genuine social organizing. And so far has receded the collective memory of social organizing that these mechanisms of control have come to be very effective. At least for the bourgeois class.

The Affair (2014). HBO.

In terms of aesthetics, this educated and mostly white class are incapable of differentiation in matters of taste. There is much liberal complaining about violence, for example, in Hollywood. And yet this wholesale and gratutious violence bothers me less than the violence of the sentimental or the kitsch. As an example, the HBO series The Affair (written by the wife of a former Clinton staffer) contains no real violence. And yet there is an indirect violence born of its white supremacist background (and all white cast) and the bathos of its sentimental script. It is the empty register in which the story takes place that is so destructive. Now some are going to object to this because on the surface this is a perfectly mediocre melodrama of rich white people. But just under the surface are the signifiers for normalizing class hierarchy and inequality. It is also particularly offensive for the way it depicts artists (novelists in this case, from some bygone cliched version of the struggling lone quasi-genius). The presentation of this melodrama is steeped in prestige symbology. And it would be useful to compare this series to, say, the films of Douglas Sirk. For the ostensible subject is the same. And yet in Sirk there is a revealing of pathology beneath the surface. In The Affair there is validation beneath the surface. And that is a profound difference. The same, to some degree, could be said of Hitchcock’s films. But it is Sirk who most clearly was deconstructing the madness at the heart of the American experience. Richard Brody wrote ….“Sirk rightly perceived melodrama as a classical genre that shifted tragic passions into bourgeois settings, thus highlighting the disproportion of those passions to the intimate banality of the action.” The HBO series does exactly the opposite. The banality of the genre is accepted as if it were classical and the passions are simply unequal to the self limiting actions. And in one way, the missing element in The Affair (and one could find a dozen other films and TV shows) is the absence of that seriousness I spoke of in the context of Swift.

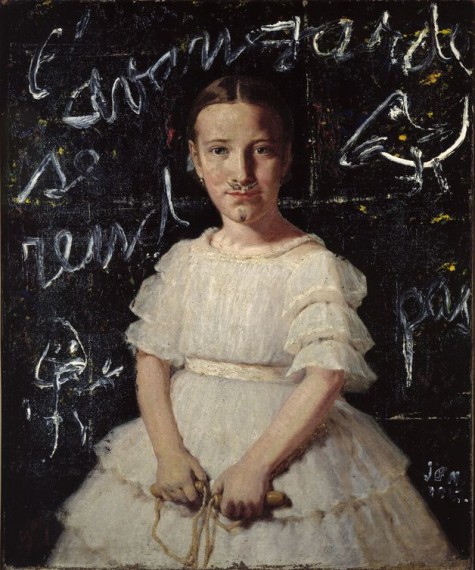

Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio

That this HBO vehicle received near unanimous praise is hardly surprising. And it would be interesting to also compare Fassbinder’s treatment of melodrama in light of all this. Fassbinder who was profoundly influenced by Sirk. In Fassbinder the surface is stripped away even one layer further. For Fassbinder, melodrama becomes political. But the sense of transgression in Fassbinder, both his queer sensibility and his desire for critical and anti-social expressions, is one that is direct opposition to the adjustment sensibility of contemporary liberal notions of tolerance. For today tolerance is only a lifestyle choice. Gay marriage is just fine, but god forbid class segregation even be mentioned. And no better proof of that can be found that the support given by liberal America to Hillary Clinton.

In Sirk the background of bourgeois banality is very often occupied with black servants or service people. For the Dane, who retired early and returned to his homeland, the viciousness of American society was something he felt palpably, and in his formally perfect films this bigotry and prejudice is never explicitly stated, but it is a mimetic reflex that shadows the hysteria and madness of his privileged protagonists as an active but elusive backdrop. The audience today for artworks, for culture, has lost or forgotten the fact that THEY themselves are always, as are all audiences or viewers or readers, a part of the drama they behold. That art, if it is to be meaningful in any way, is to be engaged on levels that reproduced both individual trauma, and collective historical suffering.

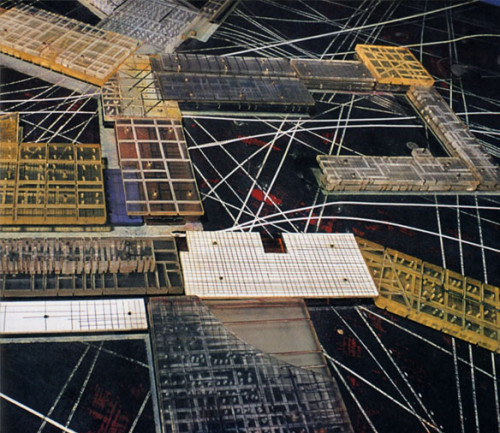

Constant Nieuwenhuys

In Goffman’s book on asylums, there is mention made of the basic guarantees that the institutionalized can expect if in turn their behavior is to be predictable. Such things as safety, limits on effort required, duration and stress. Today, it is exactly these long expected social guarantees that have been lost. Today, the public and certainly the employed public, do not even expect such considerations. Unpaid work has increased hugely, and safety is an almost laughable consideration in most corporate contexts. The public are medicated inmates in a punitive asylum run by callous guards and on both sides there is a blindness to situation. I had an argument recently about the new managerial class in the West. The question was if they were to be considered working class. And of course they are, I believe. If you must work, whatever the work, in order to survive, then you are working class. They are huge discrepancies between the managers of businesses and those toiling at manual labor. Huge. But the fact is, that managerial class has never been more psychologically buffeted than now. There is a dramatic increase in mental disorders and depression among those officially seen as at least relatively privileged. The regressive collective that Benjamin noted is true today, but it is an even more disturbed collective. One that cannot articulate their angst and one that strives, increasingly, to find scapegoats for their unhappiness. They are blind to both their own comparative privilege and to the suffering around them.

I wrote a while back that mimesis is, if traced back to early humans, tied to fear and self preservation. That the paralysis of the body was the price paid for the development of the self. And that self preservation is tied to a dynamic with subordination, and that the final surrender is Death. Art does not literally depict reality, for our reality, our perceptions and interpretation of *reality* is already compromised. Our way of seeing, and certainly our vocabulary and grammar. So art must transcribe something by way of a complex excavation of our history — in a sense. This is all stuff I have written about elsewhere, but the point here is that the mimetic (as Horkheimer said) become subsumed by various mechanisms of domination. There is another aspect to obscuring the past, and that is the veneration of a mythic past by way of monuments. Today, rather than build a giant column in the center of the city, the ruling class sub contracts *veneration* to film producers and museum curators and gallery owners. The Tate Modern extension is a form of jingoism, among its other features. It is a celebration of Capital. A monument to finance. And the contemporary museum visitor is (or the vast majority) one who is shopping for cultural experience. And this brings us back to Robinson’s essay on Benjamin from the top of this post. Artworks are commodities, first. And that sense of the economic impedes any sense of mimetic engagement, but it also encourages the easy identification with consensus. And the consensus is agreed to before hand, in effect. The consensus is one with money. With wealth. Breaking down the various layers of the representations of meaning in this identification is complex, but cutting across all of it is a regressive collective, one numbed with medication and one increasingly both mentally and physically paralyzed. I strongly suspect that pornography only flourishes in societies of paralysis. Of emotional armoring. The lost sensory awareness of our bodies and of space is compensated for with compulsive repetitive masturbatory titillation.

Abe Topor

Artworks are obscured by a fetishistic gaze. By what Benjamin saw as phantasmagoria. Part of revolutionary work is to see the object without its fetishistic quality (I’m simplifying here). James Martel, in an essay on Benjamin, writes…

“Benjamin’s program for anti-fetishism; he calls, not for the head on attack or for the permanent destruction of phantasm, but rather for something more conspiratorial (as when Benjamin writes of Baudelaire that he “conspires with language itself. He calculates its effects step by step.”) Benjamin’s engagement with representation often takes forms that seem apolitical or mystical (which might help to explain why he hasn’t always been taken that seriously as a political thinker). Yet Benjamin’s interest in art and film and theater remain highly political because, in his view, through art we engage in representational activities, we work to expose and subvert the fetishism that inheres in all forms of representation, political forms very much included.”

David LaChapelle, photography.–

The biggest danger on the left, in this context, is an easy alignment with the new populism. The fact that it’s not seen this way demonstrates just how intractable the loss of sight has become. The dismissing of 99% of contemporary art (in any medium) is a form of anti intellectualism, and the residue of Puritanism. It is the mutated ideology of exclusion. And often, when I hear praise, it is for either the ideologically instructive, and this is itself a sign of secondary consensus, or it is just the safe validation of cleverness or virtuosity. There is a delicate tension that separates social organization and cultural knee jerk consensus with ourselves. Art is not the sum of factors involved in its production, though that is certainly a big part of it. Benjamin was keenly aware of the impossibility of really stepping outside the fetishistic. And this is art and culture as impossibility. But from within that recognition of failure comes the radical quality of culture. This was also Adorno’s lesson. It is not even a primary activity for social change, but it is a crucial factor to awakening from the nightmare of Capital’s collective regression. Once Sirk is experienced in the same way as the more obviously political Pasolini, then the mystification begins to recede.

“1.1.Phantasmagoria is the screen-image which the society that produces commodities makes of itself when it refuses to acknowledge that it is essential for it to produce commodities.

1.2.Phantasmagoria is “not only” the apparition of human creations “in a theoretical manner, by an ideological transposition”, but “in the immediacy of their perceptible presence”, in an “illumination”. It is the result of an ideological process (“ideological transposition”), but it is not perceived as such. It is perceived as a pure form.”

Marc Berdet (8 Theses on Phantasmagoria)

And Berdet adds later..“It is also a specific social class that sits at the head of this process, the bourgeoisie, that generates phantasmagoria. In this way too, phantasmagoria is not general but specific. Example: Phantasmagorias of the interior, of the market, of the civilisation (Haussmann’s Paris) correspond to different specific classes within the bourgeoisie itself: the trade bourgeoisie; the industrial bourgeoisie; the financial bourgeoisie (supporting Napoleon III).

The dominant class can also spread its own phantasmagoria to the other classes. It is a weapon to neutralize other classes.”

It is the confusion of real and fictional. And often the fusion of real and fictional. But the real often IS fictional in a certain sense and that is problematic. But only in a certain sense. As Bly once said, a society that burns witches is one that has confused the mythic with the real. And that society is sick.

John, thought you’d like this review of Hamilton

https://www.currentaffairs.org/2016/07/you-should-be-terrified-that-people-who-like-hamilton-run-our-country