Henry Moore

“Militarism is closely intertwined with the interests of U.S. capital. U.S. leaders are not misguided when they impose sanctions against some poor nation or launch a war. As dreadful as the consequences may be for the victims, such aggressive measures have been remarkably effective in achieving the aims of Western elites: control over the labor, resources and markets of other nations. No challenge to the political orthodoxy of the free market can be tolerated and no corner of the globe can be allowed to remain free of from plunder and exploitation by private interests.”

Greg Elich

“The US’s psychopathology of strength, dominance, hatred of difference, driving America into a cul-de-sac of ideological hardness and inflexibility, rather dead than red (even when red is not around), is like a locomotive rushing downhill, no brakes, almost, beneath the toughness, craving oblivion.”

Norman Pollack

“Something in narration escapes the order of what it is sufficient or necessary to know, and, in its characteristics, concerns the *style* of tactics.”

Michel de Certeau

I have been thinking a lot about the ways in which political propaganda entrenches itself, and how aesthetic values shift, and aesthetic propaganda (which it is, but more below) entrenches itself. There are class segregation, certainly, in that elite Universities assist in artist careerism, and there are also ideological (all of these over-lap) niches, and niche markets, and increasingly certain, not all, niche artistic mafias operate separately. As this new first chapter in the official permanent war saga starts, I see this increased punishment meted out to those who dissent. While everyone, in a way, realizes that Obama and Clinton are both far to the right of Nixon, fewer people see that branded alternative journalism is now to the right of where the Wall Street Journal once was, say, forty years ago. Such a blanket statement isn’t quite right, but the basic impulse of that sentence is true. Now in terms of art and culture, with the now complete disappearance of the avant garde, any kind of avant garde, there remains only specialized niche producers with their niche target audiences. And the revisionism starts with the de-politicizing of the artist.

Statue of Shiva, outside CERN, Geneva.

There are two currents running through both journalism and artworks today. One is the branding. The second is is a nakedly dishonest re-writing of history. They work together, of course. There is an intellectual sectarianism, too. In literature, in theatre, in poetry to some degree, and in fine arts, there are very well defined mafias at work. They manufacture codes to communicate with the novitiates. There are words, or behavior, and certainly values (expressed as commodity loyality, brand loyality) and now such style codes have subsumed actual thought in many places.

In journalism, I think these structural dynamics are newer. I’ve mentioned VICE before, but a writer (sic) such as Danny Gold, as an example, is deeply reactionary. If Obama is to the right of Nixon (and he is) then Gold is to the right of some Hearst tabloid hack from the 20s, and no amount of cool coding can change that. He reminds me a bit of another bilious reactionary, Marc Cooper. Both spend great amounts of time on attacking leftists for, well, left politics.

L’Eclisse (1962), Michelangelo Antonioni, dr.

Gold is not unlike Nick Kristoff, too, but it’s the VICE version. Meaning, the manufacture of the brand targets a younger audience, more garage band and less Bono. What is insidious with faux journalists like Gold is that they create empty rhetoric. Empty ad copy. Words like *progressive*, as a way not to say socialist. And not to say liberal, because the connotation for liberal is now too negative. Its all about brand. There are other versions, more academic, more grounded in the style codes of higher elite (expensive) education. Words like *agency* are stuck into the middle of a sentence, for no apparent reason. And it’s tricky, because these meanings, these marketing strategies are ever changing. *Progressive* meant something else five years ago. But then the meaning of meaning has shifted. Outside of the most rigid scientific context the idea of meaning floats above our heads like Zizek’s signifiers. Empty, gaseous, and reactionary.

But, back to branding in art. The point is that heterogeneity is being subsumed by an intellectual and ideological flatlining. Everything is everything else. Running sideways across all of this, I sense, is a new return of Puritan moralizing.

Phillip King

The irrationality, the contradictions in all this, is partly what is driving the escalation in violence throughout the society. Now American society has always been violent. Always. But the violence is now untethered from cause. People are, and cops especially, increasingly violent for no apparent reason. No stimuli is needed. And the consumption of violence breeds the need for more. New medical shows now show in close up, in agonizing detail, every drop of blood, every bit of splintered bone or tumorous growth. The autopsy is now the most consistent narrative trope in Network TV dramas. Hands down. If aliens landed today on earth, and watched people for a few weeks, they would go away convinced that the primary occupation of mankind was forensics and that we suffered some form of death obsession.

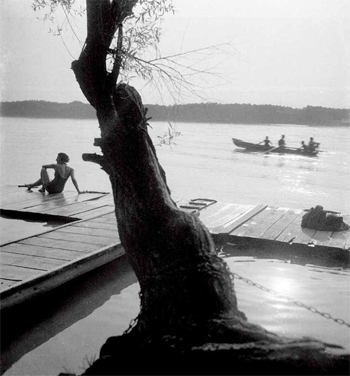

Eva Besnyo, photography.

Now, one of the problems today in trying to critique culture, or maybe just aesthetics, is that of an enforcement of the constant “now”. Jonathan Crary writes quite cogently about this. For the very idea of intentionality is dismissed, and as Jameson points out, it is very hard to do this because of the very success of the critique of instrumental reason exemplified by the Frankfurt School thinkers. And by Freud in an odd sort of way. In philosophy the ascension of a Zizek speaks to the very same mechanisms of reactionary politics and self branding as a tool of Puritanical punishment. And that punishment is reserved at every turn for anything suggestive of radical or socialist thinking. In other words the mechanisms of branding entail at the foundational level a demand to respect the status quo. Everything dissident is derided as perverse or is called Stalinist or authoritarian or just old fashioned. Anything that asks for historical vision is called a-historical. Anything socialist is called Capitalist, anti racists are called the real racists, and so on.

Pablo Palazuelo

I find that all artworks, contain a relationship to death, and included in that is contemplation of the infinite, either macro or micro, and there are countless ways of approaching this. If art is kitsch, one of the things it does is to remove anything that engages with cosmic forces, with questions of eternity, with looking backward to our beginnings or looking forward to what might be. Kitsch is about right now. Now I might argue that any artwork that actually raises a sense of awareness, even if fleeting, about the cosmic implications of our existence, is also, inescapably political. I have made the case before that abstract art is often, if not usually, more political than the overtly message oriented themes of, say, a Diego Rivera (and I think Rivera is very good). There is also the uncanny. The uncanny is a sense of something familiar, that, probably, we have repressed. Or, we have forgotten. Great artwork, even good artwork, is trying to remember. There is a built in politics of liberation attached to memory. Which is why corporate kitsch is always either about removing memory (now now now) or it is about creating false memories. The very idea of a mystery is linked to the cosmic. To the impossible. Most artists I know are fascinated with CERN and the Hadron Collider. Why? Because of the sheer practical pointlessness of it, but much more, because it is directed at what is mysterious in our existence.

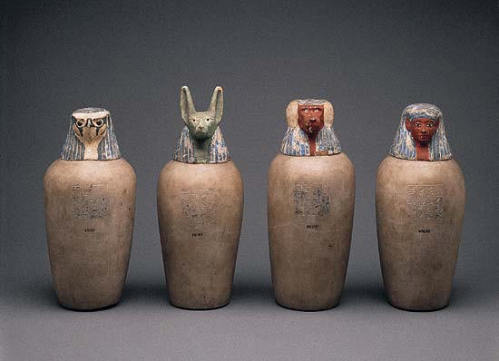

Canopic Jars, found Deir El Bahri, Upper Egypt. 21st dynasty.

The sense of infinity usually overlaps with the uncanny, and/or with Utopian dreams. Irony, this rise in a post modern ironic, is essentially a way of neutralizing an awe and wonder at the world. It is an intellectual cannibalism. The commodifying of things has, in a sense been replaced by branding. Much anti commodification artwork is there to build brand. In any case all of it removes mystery and memory, and certainly the dream life of people, and of Utopia. That is what it is does. If the Imperialist project of the ruling class is to CONTROL EVERYTHING, then promoting work that suggests there is ONLY our specialness (meaning the ruling elite), and our unique talents and beauty will be standard. Work that asks too many questions, aesthetically, is removed. When innovation is rewarded, what is meant is the opposite.

A certain quality of meditative attention is an implicit question; the infinite, and eternity are all gathered under the aegis of immaculate detail and craft. The opposite, a craft, meticulous or otherwise, without memory or without dreams is artist as simply technician. The contrived attempt for *weird* effects also is a way of removing the uncanny. For the genuinely uncanny can never be planned for, and attempted, consciously. The one link in artworks from antiquity through today is that of seeking the unknown, a revelation, a recognition of the infinite, and perhaps that is best or at least most clearly realized in contemplations of mortality. The obsessive splatter films and zombie films, along with all else they are, are also ways to crowd out reflections of mortality. The vampire, that product of bourgeois hysteria, is also in its overdetermined way, a stand in for the genuine spiritual dread of our own death. Fear and trembling is now the cruel superiorities of Jerry Seinfeld or Lena Dunham.

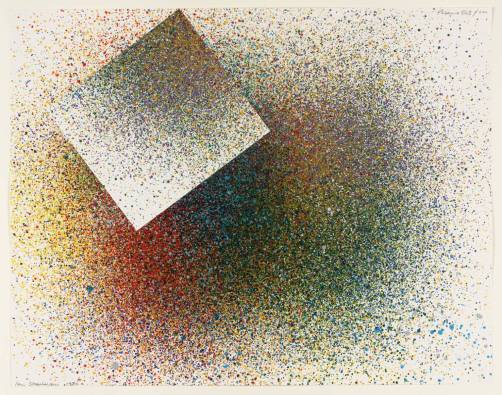

Ian Stephenson

In theatre, one can go back to an avant garde in Germany after WW1; the writings of Piscator and Toller say. Now they shared similarities while politically taking somewhat different paths. This was still, all of it however, an answer to the naturalism of Ibsen and Chekov and even that outlier Strindberg. As Raymond Williams wrote; “Sexual liberation, the emancipation of dream and fantasy, a new interest in madness as an alternative to repressive sanity, a rejection of ordered language as a form of concealed but routine domination: these were now seen, in this tendency, which culminated in Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, as the real dissidence, breaking alike from bourgeois society and from the forms of opposition to it which had been generated within its terms.”

Now, Piscator’s Fanen (Flags), a sort of Brechtian epic about strikers and labor, is today, in spite of an intelligence applied to its staging, largely forgotten and feels like something of a relic. Why? Well, one, the writing lacks that attention to the cosmic, if that’s how we want to describe it, and its finally a *message* melodrama. In England at this time there was mostly George Bernard Shaw and a bourgois cynicism. In Ireland there was, however, work of some lasting merit in O’Casey and even W.B Yeats. Today this works seems in some ways more radical than Piscator or Hollar. But it was Brecht with whom a certain confluence of factors collided. I still find Baal and In the Jungle of Cities his best work. But Brecht is a special case and worth an entire posting to try to tweeze apart. My point here is that in Brecht, in Baal, one hears the hallucinatory echos of Buchner, while by the time of Mahagony, that has gone silent, replaced with didactic oration (of course the inclusion of Eisler changes everything). One of the continuing problems with the left today is their failure to look past artworks that just serve as echo chambers for their preferred political rhetoric. In painting its the crappy community center murals everyone feels compelled to applaud, or it is the never ending endorsement of overtly political message. The day a socialist openly endorses Genet or Pinter or Beckett as great playwrights, or prefers Rothko over Rivera, then I know progress will have been made.

Jeff Koons

The left today, is often guilty of falling prey to the accommodation demanded by the logic of the Spectacle. The tacit rejection of much of the Frankfurt School has to do with their emphasis on the subjective, Freudianism, distrust of proletariat organizing (elitism) but most of all, their preoccupation with art and culture. Of course, the Trotskyists out there are simply stuck in a vocabulary of 1918, and what Russell Jacoby called a ‘dialectic of defeat’. Nothing is ever socialist enough. So they can agree with attacks on Chavez by cretins like Danny Gold because to them, Chavez wasn’t a *real socialist*. I can’t count the times people have said to me, ‘oh, if you were a real leftist’. I’ve no idea, finally, what they mean. Except that it is a form of delusional thinking.

Boesendorfer Piano, limited edition #225. Design Hans Hollein, 1955.

Now on the other hand, it is time for radical voices to stop whispering or looking to be reasonable. The people in Serbia are not fooled by U.S. rhetoric, the people In Iraq certainly are not, nor in Rwanda and Ivory Coast and Haiti and Yemen and Venezuela or Guatemala. It is therefore important to know who your enemies are, if you are looking for social change. But it also important to start seeing the aesthetics of politics as well as the politics of aesthetics. In the First World, there is a need to develop aesthetic resistance to the overwhelming effects of a business culture. A business culture in service to the ruling elite whose desire for control is absolute. The aesthetic codes of, for example, the Coen Brothers are reactionary. They are regressive, and they culminate in a belief in and for the status quo. The form, the intentions, the lack of dialectic movement in narrative, and perhaps most of all, it is what ISNT there that is most telling, all of it contributes to their marketability, popularity, and superficiality.

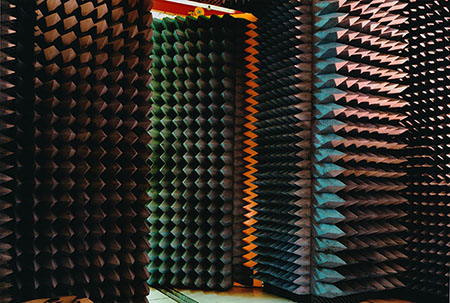

Lewis Baltz, photography. ‘Anechoic Chamber’, France Télécom Laboratories

See, anyone who makes a movie is reflecting something about film history. This is true with any artform. They are also, to a degree, making a statement about how the artwork is made, and about the labor value and cost of production etc. What Koons does is simply frame the cost and process as art. In so doing he erases the history of Jeff Koons. Certainly there is no unconscious, and no memory. In Hollywood today, there is an increasing stridency to the comedies, and an increasing bathos to the drama (if that were possible). The dramas, however, allow for this chronic addiction to violence. The Coen Brothers make movies, and this is to their credit, that are not orgies of violence. What they are, however, are mean spirited and cruel. True Grit was not an homage to either Wayne or Bridges. It was an unpleasant homage to the Coen’s own brand. Everything is brand.

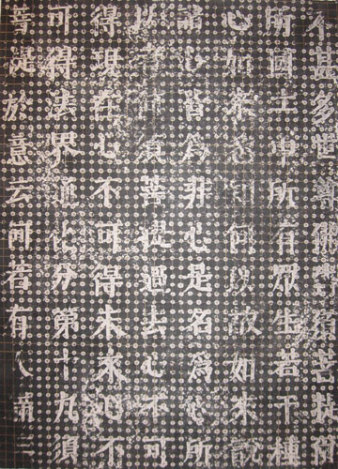

Hu Qinwu

“The common consent to be positive is a gravitational force that pulls all downward. It shows itself superior to the opposing impulse by refusing to engage it.”

Adorno

The smiley face subjective, the constant enforcing of strategic thinking, the insistence that to be too critical is ‘not useful’, has rendered the populace mute in the face of endless horror. When some, unable to endure more, speak out they are usually shamed, ridiculed and scapegoated. They are not being useful. This position, in narrative, is often masked. The superficial cynicism or meanness of the Coen Brothers is actually just a fragile patina that obscures their basic smug contentment. Their world is one where every meal is a ‘happy meal’.

The Coen’s only make genre films. Everything is a gloss on other films. If I were to single out the most, at least, ambitious of their dramas, I might end up with Inside Llewyn Davis, The Man Who Wasnt There, A Serious Man, and No Country for Old Men. In each there is a strange sort of quality to the narratives, which seems to revolve around an absence of the uncommunicable. Now, I have a certain sympathy for each of these films. But there is at the heart of all of them something dishonest. A certain tricking of the audience’s engagement. The failure of narrative is presented as a failure of the audience to ‘read’ the film, the film is just too good for us.

Awoiska Van der Molen, photography.

In The Man Who Wasn’t There, Ed Crane, the character played by Billy Bob Thornton, is presented as a sub-everyman (“I’m the barber”). The voice over is both a parody of a noir device, and a way to suggest that its ok if nothing is actually happening on screen. Shot in black and white, by Roger Deakins, the neo James Cain story is a deconstruction of work from writers such as Cain, Goodis, and Cornell Woolrich. The central device is a variation on the ‘wrong man’ theme. The problem is, there is so little there that we are left to (and meant to) contemplate the cleverness of individual scenes. Critics (like Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian) suggest the Coen’s world is both familiar and unfamiliar, and that they therefore achieve something unique:

“As in so many of the Coens’ films, an entire universe is summoned up, partly recognisable as our own, and yet different, a quirky variant on real life with its very own fixtures, fittings and brand names.”

The Man Who Wasn’t There, 2001, Coen Brothers.

One of my very favorite photographers is Awoiska Van der Molen. There are very few photographers of her weight and sense of the cosmic. In one sense she serves as another example of what deep looks like contrasted with shallow. For there *is* a difference. Here is a recent excellent review from Sean O’Hagan: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/sep/26/photography-awoiska-van-der-molen-sequester-canary-islands-landscape-nature

Veronika Voss (1982) Rainer Werner Fassbinder, dr.

The Coen’s recieved a huge amount of adulation for No Country for Old Men. As a kind of disclaimer here, this is a book I have a certain attachment to, and respect for, and one, as it happened, that I read in one night while sitting at the Warsaw Airport Hilton, in the lobby, where I was stranded. Perhaps that was the perfect place to read it. But there are scenes in that book of such chilling cruelty that it’s hard to find the comparison. And part of the reason is that Chigurh, the proto-demon who ravages all in his path, a sort of colonial ghost, Indian killer, and Puritan all wrapped up in one, stalks the landscape of the book as an Old Testament curse. He is described by McCarthy economically, mostly it was his pale blue eyes. This minimalist vision was clearly the European conqueror, the scourge of Manifest Destiny, returned. So what do the Coen’s do? They cast a brown eyed Spaniard. Of course.

The strange absent elements in the Coen’s work is not that taciturnity of character, or voicing, that one that might find in Hemingway. For it doesn’t come out of the moral tensions of their work, and that’s because, well, they have none. These are astoundingly empty films in the end. Often well made and I think on balance they are highly competent technical film-makers. But even that, as is the case with Deakins work on The Man Who Wasn’t There, the sense of looking, that sense of deeper scrutiny you find in Antonioni or Bresson, is missing. Another film shot in B&W, as an exercise in dissecting nostalgia was Fassbinder’s Veronika Voss, (1982), and shot by Xaver Schwarzenberger. It is a spin on the Sunset Blvd theme, but it is inextricably tied into post war German society, to the spell of American culture, and of moral cleansing. Compare the sense of dread, of moral sickness, or failure and disappointment in that film, with the Coens work. In A Serious Man, the Coen’s perhaps come closest to actually making a movie about something. Its failings are familiar to us from all Coen Brothers work, but at least there is a sort of odd purpose to the elliptical narrative, and more, to the witholding of the central character. Its possible the ironic title is actually self-analysis, and if so, that might serve as their smartest bit of product. Larry Gopnik is another of the Ed ‘the barber’ Crane characters in Coen Brother films. I desperately wanted this film to be better than it was. For watching it, I kept thinking, this is being driven along by exactly what is so often missing in their work, the uncommunicable, the fleeting meaning that lives in the interstices of story. But even here the final scene resorts to a goofy unseriousness. These are guys who just cant handle the real. That impulse to destroy even their own work is mirrored in the passive aggressive nature of so many of their characters. The gratuitous nastiness. It is there in every film. Still, the brothers clearly are more at home in a small mid western city, the Jewish tract home end of it, than they are in the Southwest, amid Mexicans, narcotics, and preening Texas machismo.

Kenneth Armitage

That the Coen Brothers are the most respected filmmakers in America today speaks to the shallowness of the society at large, because they have yet to make a single memorable film. I would wager they are, if one polled mainstream media critics, the number one film artists in the country. Given that Speilberg is aging, and P.T. Anderson is too operatic. Even mainstream America is suffering insulin shock from Wes Anderson’s work, and that leaves only Linklater, and honestly I’d sit and watch all thirty years of the Coen’s before I sit through another Richard Linklater film. And yet, it may be that Linklater is soon to take the populist baton from Joel and Ethan. And honestly, who else is left in American film? Darren Aronofsky is essentially a hack, David O. Russell an elevated hack, and David Fincher a talented hack with elevated ambitions. Cronenberg is Canadian, and has made fascinating work (Videodrome is a small Dickian masterpiece) but most recently has taken to high brow literary adaptations with disastrous results (well, stooping to Bruce Wagner for a parody take down of Hollywood is just, so, well bad on so many levels I don’t know where to begin). I despise lists, and I refuse to indulge one here, but Tommie Lee Jones might be the most interesting American director working right now, with two pretty admirable films made (The Homesman, and The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada). If not Jones then certainly Todd Haynes, whose Mildred Pierce is a far more radical re-thinking of noir than the Coen Brothers managed. In fact Mildred Pierce might have been one of the best films in the last five or six years. Or ten. Lynne Ramsay (who in fact is Scots, but whatever) is interesting, as is Kelly Reichardt. Both may develop and produce work of importance. The allure of Hollywood is a sickness, though. And its not an easy minefield to navigate, to employ a cliche. And that is the effect even thinking about Hollywood has on me. I start writing in cliches. The first feature of Alexandre Moors (Blue Caprice, 2013) and the remarkable Mister John (2013) by Irish husband and wife team Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor were both exceptionally good films. And I’m writing here only of English language films. It is interesting that Mister John is here compared with Antonioni. http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/interviews/quiet-irishman-mister-john

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005), Tommie Lee Jones, dr.

It is important to see in Hollywood film, that it is remarkably rare to see films that are not so mediated by studio interests and values that they don’t turn out as simply pure propaganda for the ruling class. Either that or valentines to the Pentagon or to U.S. police departments (increasingly the same thing as the Pentagon). But to go back to L’Eclisse, and see it now, there is such an acute aching desire that activates that film, and perhaps in varying ways it activates all of Antonioni. The spatial distances of that film, far more than L’Aventura or La Notte, are part of the dying of the possibility for love. The financial markets, the coldness of Alain Delon even when trying not to be, and Antonioni’s sense of searching for presentments, portents, amid the congestion of modern Rome. The film is about both the aliention of business, the soul killing surrender to money, and of the spaces of memory, and all of this is just off screen, just behind the walls, just in the next room of the cafe.

The duration of scenes, the patient wary observer of the strangness of each house, each street, is what invites the viewer to share in the dream. Is there any such moment, even one, in any Coen Brother’s film?

John Kirby

The most disturbing aspect of contemporary culture and art is the branded populism that cloaks itself in high brow rhetoric. Where once Adorno and Horkheimer could analyse Astrology columns and soap operas the better to extract structural and ideological meaning, today the critical thrust has been subsumed by institutional ratification of kitsch, of seeing in junk a subject worthy of analysis not because it reflects larger socio-political issues, and spiritual ones, but because it is now the standard for culture and art. When Susan Sontag wrote her essay on Camp, deeming it an elite appreciation of junk, it was done (however simple mindedly) within a larger critique of interpretation itself. In other words the lyrics of Madonna are treated less as revealing of ideological codes than as simply poetry. Part of what drives this is, of course, the acceleration of domination, of neo liberal control of thought, but it is also from another direction the idea that these are popular artforms. The missing ingredient in mainstream analysis of culture is firstly, Marx. Second, and equally important is Freud (and probably Debord and Lacan and etc). But it is primarily the ignoring of how this crap is produced and who produces it. The backdrop of white supremacist neo-liberal Capitalist ideology is just erased. That backdrop actually contains all discourse. That is what is being forgotten. And because of that there is a growing accommodation to the status quo. The unstated but assumed correctness of U.S. Imperialist narratives is rarely questioned. One can argue over racist or misogynist issues from within this contained realm of discourse, because token debate is allowed and even encouraged. But to suggest that, say, a hit show like Homeland is bad, that is an acceptable, if minority opinion, but to analyse it as pure Imperialist propaganda, as political crypto fascist, well that would result in open attacks and ridicule.

what do you think about Atom Egoyan

As always, lots to contemplate here… ““The common consent to be positive is a gravitational force that pulls all downward. It shows itself superior to the opposing impulse by refusing to engage it.” Do I dare tweak Adorno a bit and exchange “be positive” with “be in-line”, “be in agreement”, or “to please”? For it seems that this is one desired goal by the current media/art: to have concensus, no matter how shallow/superficial. My introduction to Koons was while working in Penny Pritzker’s home (yes, the now Sec. of Imperialism, I mean Commerce). A fellow carpenter who also happened to be an artist told me about the Lobster “sculpture” hanging from the ceiling in the foyer. “It’s made out of metal but looks like an inflatable lobster raft” he informed me. I didn’t get the point and still don’t. But that’s the point, I guess. It seems most modern art is all about “reactions” and “movements” and “who” is reacting to this person or that movement. One has to know a lot today in order to “get” modern art. There’s a succession that needs knowing. I recall reading Calvin Tomkins’ “Off The Wall” and how he tried to explain it all. How does one explain Rauschenberg’s “Monogram” (angora goat with a rubber tire around its waist)? “It is neither Art for Art, nor Art against Art. I am for Art, but for Art that has nothing to do with Art. Art has everything to do with life, but it has nothing to do with Art.”- Robert Rauschenberg, 1977. Compare that to an old-timer, Sir Phillp Sidney who stated (I believe in his Defense of Poetry) that art should both be pleasing and instruct. Not sure I agree with this totally either for great art does make one feel uncomfortable at times, as well. It’s not always about pleasure, is it? Art empty of content versus one that has a soothing message (propaganda?). I’ve only seen one or two Coen Bros. films, but I get the sense with all of the famous people that have bit roles in their films that there is a clique of some sort; an attitude of “we’re a part of this and you’re only a spectator”, that there is something worth understanding because they’re all a part of a big film made by famous directors. Maybe the point is to make us feel left-out so that we’ll sell everything we have (even our souls) to become a part of their narrative/”film” which in the end “pulls all downward”…

Its interesting……….since i posted this, a big fb thread was started. A jillion comments. All on this thread, maybe twenty people, LOVE the coen broth. And are highly agitated about anyone criticizing them. A lot of the comments are about the fact they are trying to ‘entertain’ not create existenital drama. And, everyone, and this is a smart-ish group of white people, understand this is all irony and what Im hearing is, they like it that way.

I have to reflect a bit more on this thread. Anfd also on your comment robert.

As for Egoyan………..I loathed Sweet Hereafter……it struck me as so wrongheaded, and manipulative. And Ive not liked much else until The Devil’s Knot. Which of course mostly was met with derision. But in fact I thought rather good in a strangely restrained way.