George Ault

For whatever reason, I have been thinking a lot about the artists that developed in the first two decades of the 20th century, in the United States. The last strain of realism, but a realism that had already felt the rise of cubism and surrealism, and which held onto its sense of realism in a particular sort of way. One can also look at this regionally to a degree, and perhaps in two generational divisions. But this was the non-corporate realism of a vision influenced by Quakers, and Amish, and by manual labor and farming. And by factories. It was work done outside the “Art Market”, largely, too. George Ault is perhaps the most siginificant, but Charles Sheeler certainly, and a generation later Ralston Crawford. The term “precisionist” is given to the movement, but in a sense when you use that term, names such as Charles Demuth and Stuart Davis come to mind. Ive nothing against either, but the real deep history of realism in the U.S. links to Ault and Sheeler and maybe Crawford and Francis Criss, or Elsie Driggs. The Met did a show on Precisionsim, and the cataloge read:

“The Precisionists borrowed freely from recent movements in European art, including Purism’s call to visual order and clarity and Futurism’s celebration of technology and expression of speed through dynamic compositions.”

Except that’s not true. It’s true, MAYBE, of Demuth and Davis and possibly Shamberg. So perhaps Im making an argument to put Ault (whose name isnt even in the Met show) and Sheeler and Crawford, and even Louis Lozowiak, and later Edward Biberman into their own category.

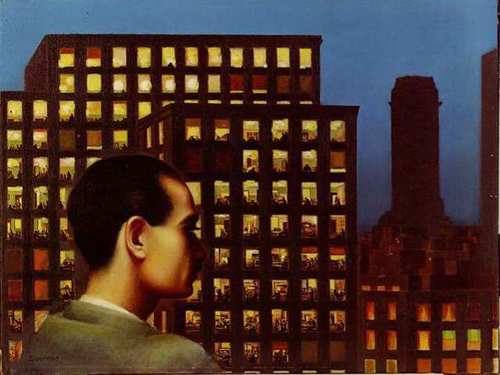

Edward Biberman, self portrait

There is something in the work of Ault, and Sheeler, and later Biberman, that feels relevant today, that feels as if it a last vestige of what ‘looking’ once meant. Looking very hard at something.

But this is work that has been de-valued a good deal. Read this from the New York Times on the Precisionist painters…

“But often Precisionism seems less a reordering of reality than of received European styles into a kind of softened, easy-to-digest form of modernism. It was America’s answer to Cubism, Constructivism and Futurism rolled into one, mated with a plain-spoken, conservative local realism (part Eakins, part folk art, part Ashcan School without the Ashcan sentiment) and aimed at the obvious — the all-American array of skyscrapers, grain elevators, factories and machines that was proliferating around it.”

Charles Sheeler

What is softened in Sheeler or Ault, or even Driggs, that one can see in Cubism? Or Futurism? No, the fact is quite the opposite. Cubism actually, when you look at it now, feels design-y, and maybe something else. Maybe there is something slightly easier, actually, in some of the early Cubists than in the best work of the early century realists in the US. There is a mediterranean comfort, and relaxation. There is madness in Ault and Biberman and Crawford. The antenna like reception to the coming waves of social domination in the machine. Why anyone thinks Sheeler was valorizing industry is beyond me. He saw madness.

George Ault

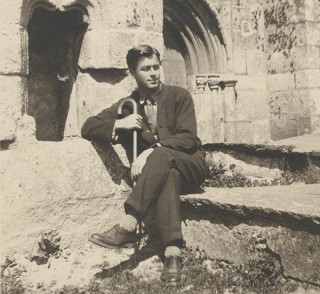

Of course the quote above is from Roberta Smith of the NYTimes, former secretary for the Paula Cooper gallery in NY, and late of Grinnell College in Iowa, and who worked her way up writing free reviews for Artforum. Why do such philistine elitists have such authority? Grovelling has its rewards I suppose. Oh and she is married to Jerry Saltz the editor of New York Magazine. And what of Ault? If there is a more neglected artist in the US, at least of this period, I cant think of who it might be. Ault was a strange troubled man. Born in 1891, he died by suicide in 1948, after wandering out alone in the dark, in a severe snow storm in upstate New York. Ault painted the night more compellingly than any other American artist. Nobody painted the darkness as well, not since Carvaggio perhaps. Ault was born in Cleveland, and lived part of his youth in England. He studied at the St John’s Wood School of Art. When he returned, after travelling around Europe, he also began drinking, and quickly his drinking exaccerbated his already sketchy personality, and this pretty much removed Ault from career possibilities. He lived many years in Woodstock New York, with a second wife, and in penury. Ault’s paintings of sunlight are not of as much interest, but his nights are where he went to confront his madness, and literally where he went to die, eventually.

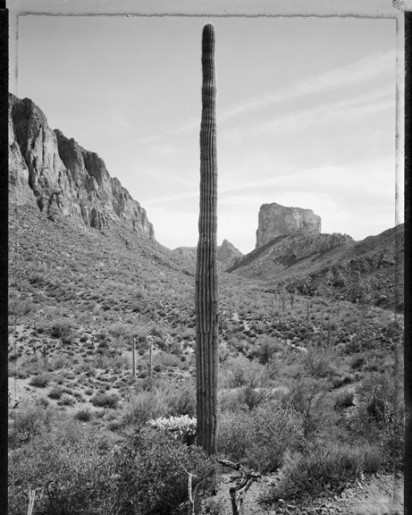

Mark Klett

But this is my point, critics like Smith, and 95% of the rest writing in Arts journals, are only parroting ideas, usually diluted, from previous arts journals, and rarely does anyone venture outside the accepted wisdom on subjects. Ergo, Precisionism is minor, imitative of Futurism, etc. Firstly, lets discard the term Precisionsim since none of the artists so labled ever used it. Secondly, I dont think its related much at all to cubism. It IS related to the Quakers and Lutherans of the mid west, Michigan and Minnesota, and to the cold ennervating winters on the plains. To the sense of isolation. American art in the 20th century came out of a forboding, the great world wars were coming, and if one looks at William Carlos Williams, or Charles Ives, or, well, Charles Sheeler and George Ault, one sees this distrust, the feelings of alienation, and lack of emotional warmth in the landscape. This was not sunny Mougins, or the Greek Islands. This is the miserable unsympathetic frame of American culture, the one D.H.Lawrence wrote of, the stoic heart of a killer he said. That is what is seen in the work of American realists. The eventual turn to abstraction was inevitable, and later to minimalism. For perhaps that is where the madness led.

Francis Criss

The Indian Killers and scalp hunters, the railroad camps, the Chinese dying in the thousands, the developing industry in the mid west; this was the land of Manifest Destiny, and of blood. None of this is the picture I remember being given in school. It is not the America a Roberta Smith thinks of, its not the reality of daily life for gallery owners in NYC. One of the notable small side bars in this all, is the sense of anarchy in US art seemed to travel west. New York of course remained central, and often those westerners went East to work. To look for a career. But among my favorite artists have been those like Ralston Crawford, or Edward Biberman (whose brother was one of the blacklisted Hollywood ten) who captured the small promises of the left coast. Later Diebenkorn would, and Frankenthaler. Crawford was born in Canada, worked for Walt Disney for a while, and studied at Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles. There is not the same suffering in Crawford, as you find in Ault, and perhaps he is too facile, but at his best, it is hard to imagine what is better in early abstraction.

Ralston Crawford

Raymond Chandler captured the world that Biberman and Crawford painted (often) and it was a landscape in which the toxins seeped to the surface as the ground unfroze. California is the French Riveria of the US, and LA is a metastasized Marseille, a glowing tumor on the left coast. The sense though, is a basic repression, and it is there in Sheeler and Ault, and it is there in all the early 20th century realists. It is not written about, and Artforum or October or ART, do not track the evolution of the american consciousness through the acute pain in its images, the insanity you see in Francis Criss, or the sense of hoplessness, often, in Elsie Driggs or pessimissim of a Biberman. The story of America’s century seems to me to be one of courage on the left, in civil rights, in the fight for Unions, and later the institutional racism and the construction of a true American gulag, and through it all the anti communist hysteria of the government. If the CIA helped bankroll the Iowa writers lab, they also were looking, at all turns, to contain radical thought in all of culture. And to promote the naturalness of elite white authority. The revisionist history of “America’s Century” is that the US spread progress and knowledge and democracy. It did the exact opposite. The story of the United States is the story of Puritanism, slavery, and the genocide of 600 tribes. Everything unfolds from those three realities. The Calvinist and Lutheran and Puritan sensibility has always permeated the U.S. That inflexible, cruel lover of violence. For the masculine in the US is always about shooting someone or something. It is the story of the squashing of progressive movements, and of revanchist tendencies. Nothing hurtful doesnt come back in America.

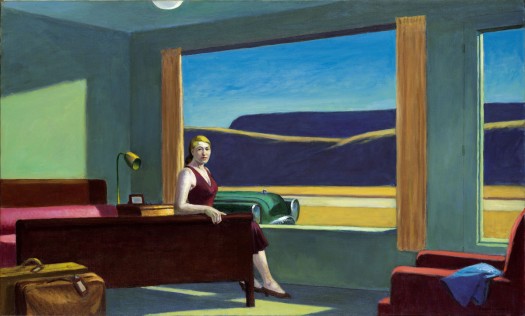

Now, Hopper is often lumped in with Sheeler and Crawford. And maybe thats correct. In 1960 Martin Freidman, then director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (among the best directors ever, I want to add, at any arts institution) curated a show of Precisionists, and he headlined with Hopper and Sheeler. While it was an important show, because in 1960 nobody remembered George Ault at all, it still operated from the belief that Sheeler and Drigs and the rest, believed the industrial landscape was “beautiful”. Recently in San Francisco there was another retrospective, taking a not disimiliar line. Hilton Kramer wrote:

“There was nothing in the way of social analysis or social criticism in the Precisionist outlook. Precisionism was not a documentary style. It took no interest in the minute observation of urban life. It did not concern itself with the social or economic implications of industrialism. It was not an art of social consciousness. It looked upon the world of skyscrapers and smokestacks as something especially beautiful—a new beauty that was uniquely the product of the machine age. From this beauty, moreover, it drew its models and its program, which was to produce an art that was as sleek, as hard, as streamlined and immaculate, and as monumental as the industrial objects and structures that inspired it.”

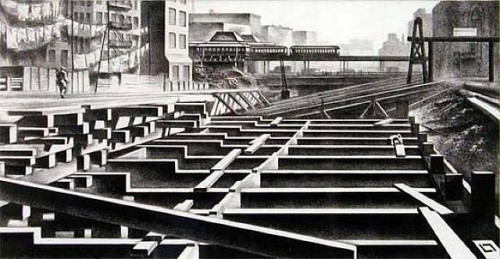

Louis Lozowick

This is correct right up to the place where he says “beautiful”. For that is correct if you are writing about Demuth or Stuart Davis, but its not right about Sheeler or Crawford or Ault. Nor is it right about Lozowiak or Biberman. But these are all artists who were not from elite institutions, trained often outside the mainstream (Sheeler was a commercial photographer, and Biberman the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts). Hopper occupies a unique space in the critical landscape of the U.S. Not embraced as ‘important’ until pretty recently, I think Hopper now looms are the spectral ghost figure in the work of all american realist painters. He is the painter of lonliness and alienation. The echos of Manifest Destiny, of expansion as a revered value, is reflected in the sense of openess, and of space, in the American West. From Melville to painters as varied as Barnett Newman, and Richard Diebenkorn, and photographers such as Baltz and Deal, and a dozen others, the quality of space hovers above their aesthetic. This is wildly generalized, but I wanted to dig into the manufacturing of a false narrative for artistic production in the U.S.

For the real story of American art, I believe, lies in the sense of fear and paranoia, of madness, that so many artists intuited in the early 20th century. That period between WW1 and WW2 was incorporating a host of influences, but primary in a good deal of the work, was the feeling of dread, that the new highly industrialized system of production, or urban growth, and of state authority, signaled a collective repression, and that this repression meant collective insanity. World War 1 was the fulcrum, the industrial designing of death, the scale and anonymity. There are few crowds in the work of Sheeler, Ault, Hopper even, Lozowick, or Biberman, or Lewandowski. Alienation was the most common currency, visually, and the emotional landscape is hardly filled with optimism in any of them. Nobody returned from WW1 believing the bullshit Roberta Smith or the Met writes, nobody came back from Europe thinking industry and science would make life rational.

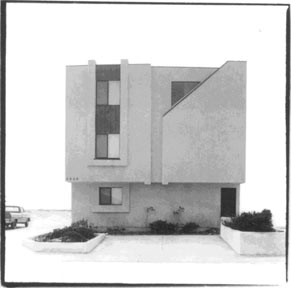

Judy Fiskin

The Metropolitan Museum catalogue on Sheeler says this:

“In late 1927 and early 1928, Sheeler spent six weeks documenting the Ford Motor Company’s automobile plant in River Rouge, Michigan, as part of the promotional campaign for the release of the Model A Ford. Sheeler’s thirty-two photographs of the Ford plant depict its acres of gleaming, massive machinery, rather than the human process of labor. They celebrate the company’s—and, by association, America’s—ideals of power and productivity, although there is also a strangely forbidding atmosphere to the unpopulated scenes.”

Indeed. The master narrative for American society was, and is, “productivity and power”, but the hidden narrative, even the secret narrative is madness and murder.

There is also the creation of a hidden idea of ‘space’. I suspect that architecture has always been intersected with ideas of immortality. And immortality implies rituals and cosmography. But American space creation is defensive, the vernacular architecture, while mediated by economy, and the maximizing of profit, can also be seen as defensive wounds, the scars on the arms of murder victims as they tried to fight off their attacker.

John Brinckerhoff Jackson

This period between the wars was an epitaph for realist painting. There was really no irony, no particular social commentary (perhaps in Hopper, but I’m not sure) and none of these painters can be connected at all to the ‘scenes of life’ group, or the Ashcan. These are, I think, the most metaphysical of American painters. They are looking at the material world as those at a Mennonite meeting might, but this is also not quite true. For they were all sophisticated readers of culture, of society, and of architecture. In this sense they did in fact share the same fascination with industry that the Constructivists did. But the Russians politicized this fascination, and Sheeler et al made it both psychoanalytical, and spiritual (or cynical…in the case of Biberman). So I think the forgetting of these painters has to do not with some inherent smallness, but with and because of their unadorned savy sensibility. There is a quality of looking but not buying. They are the opposite of how most catalogues describe them. The coming decades of marketing and hyper expansion, and the eventual destruction of the working class, the eventual pauperizing of the working class, is evident in all this work as prophecy, but hidden.

Edward Lewandowski

These were the secret readings of hard pragmatic painting. Of course there are great variations within this group. Sheeler is austere and precise, Ault tormented and mystical, Biberman cynical, Crawford the most sober and balanced. Lewandowski is possibly the most actually seduced by his own subject matter…but even in his work, its hard not to feel the sense of evil portents lurking in the shadows. Or of violence.

Then there are semi related abstract painters, people such as Marsden Hartley and Arthur Dove. When I look at Dove, it’s hard not to see the spiritually intoxicated version of Sheeler. Same with Hartley to a degree. If one of the arteries through which flows some of the hidden truths of the US is “blues” like Willie McTell, and proto country music such as Hank Williams, then there is a secret fatalistic truth carried along and suspended in the capillaries of the larger arteries of these painters…to really stretch a metaphor. But there is a truth too, in the work of Sheeler and Ault, and maybe at times Biberman, Crawford, Criss, and Dregs and it is there, but slyly, and looking back. It stares out from the empty windows, from the shadows, and from around corners. Hopper only painted one or two paintings in which the human subject looks back at the viewer. But in Sheeler and Ault, there are no human subjects. The subject is implied. The subject is not the great blast furnace or bridge: thats the ideological fantasy of the NY Times. The subject is not present. He or she is hiding. The police are looking around this area. There is an APB out. But the subject is not missing. The subject is alone screaming or crying or cutting his or her wrists.

Woodbury County Courthouse, Sioux City IA. George Elmslie architect, 1918

The real narrative has been fear of social domination, of authority. All along, this is the hidden story, the sub text of the American Century.

And one sees it today in corporate news coverage. The control by the state of “message”. The “message” of the Olympics is ‘Russia is bad’, and full of stupid people. You see terms like “cossacks” used a lot. You see the control in what is covered and what is NOT covered. The prison complex is NOT covered. Prison hunger strikes are NOT covered. You see it in the idiotic disinformation on the planned covert destabilizing of Venezuela (as an example). In the endless rhetoric devoted to justifying US military occupation of most of Africa. The US financial sector is fragile, up to a point, but the military strides the planet like a sadistic but not very bright giant, punishing whoever it decides it doesn’t need. But that’s not the impression the media provides. The media distorits Israeli violence and apartheid. It treats all dissent in the US as either terrorism or kooks. And most of all, the control is exercised via “entertainment”. The constant, CONSTANT, outpouring of stupidity. “Reality” shows, game shows featuring willing humiliation, or I suppose bought voluntary humilitation. The militarized spectacle of professional football. And the endless narratives that hinge on violence against women. And really, violence period. Violence is so pervasive, so normalized, that one would think daily life in the U.S. is just one long gunfight.

Edward Hopper

This is all stuff any half intelligent person already knows. But I am suggesting that in the same way the Iowa Writers Workshop, and more, MFA writing programs overall, impacted what ‘fiction’ was, so the marginalizing of this group of realists was in the service of keeping actual “looking” out of the equation when the public thought about painting. The misreading of the left though, had to do with factoring in Abstract Expressionists as part of the discouraging of looking at daily life. That was happening, firstly, before the Ab Ex movement happened, and secondly, it wasnt about figurative or non figurative. For there were perfectly acceptable figurative artists. And I’d suggest those were the ones that led more directly to pop art. Warhol can be seen as linked more closely in sensibility to the ernest social criticism of French realists such as Daumier and Courbet, and certainly, the camp ethos might enter in how today’s viewer sees the Ash Can painters, or more obviously someone like William Adolph Bouguereau. Now, it was painters like Bouguereau that Courbet was rebelling against (partly) — and yet who looks more relevant today; Courbet or Bouguereau? And I dont think I’m even asking who is “better”, because by all standards of obvious traditional taste, Courbet is better. But honestly, Bouguereau almost seems surreal today, and paradoxically more intriguing.

William Adolph Bouguereau

Gustov Courbet

Painters like Dove and Hartley were quintessential American artists. The final endgame for encroaching state engineering was found in Rothko and Newman and Pollack, who perhaps became exemplers less of individualism, and more of ecstatic emptiness. The Mexican muralists were travelling another road. Scale, and the principles of muralism itself served up clear ideological messages, and yet that work, too, transcended its mandate. But the work of William Merritt Chase, or Winslow Homer, or Whistler, is the work of the “beautiful real”. It depicts a reassuring reality. Time stops. A “moment” is captured. The viewer can take it in, the signposts are familiar, and the rendering of life is, finally, generalized. Compare Whistler’s outdoor scenes to those of Constable. Compare them to Ault. The masses are trained to think of reality as defined and contained by the visual cues found in certain ordained artists; Chase or Whistler, or Norman Rockwell (the obvious vulgar example) and further back to Church and Cole. These were pov’s that amplified American greatness and strength, and they presented idealized pictures of nature. Nature as diorama. Nature as carefully beautiful, as found in the Natural History Museum. Worth mentioning an early outlier from this school and that is Martin Johnson Heath. Now, Ive always been fascinated with Heath. He liked to paint hummingbirds, orchids and salt marshes. He was a strange man (surprise) but his work, for me anyway, is the precursor to painters like Ault. Heath wasnt much valued during his life, except with working class art lovers. He gave away a lot of his work, and stuff still turns up at garage sales across the U.S. Now I suppose one can see Heath as also laying a foundation for Thomas Kinkaid and the like, but I’d argue that’s wrong. It is understandable, but it’s wrong. For there is a personal darkness in Heath, and you quickly feel that the real subject is not that pink orchid. It is sexuality itself, it is desire, and carnal yearning.

Martin Johnson Heath

Heath is the great painter of fecundity and moisture. That fertility dries up in American realist art, and between WW1 and WW2 the final coffin nail is hammered in by the Precisionists. It may be, really, that a Rothko or Kline were returning to something carnal. Or De Kooning, but also I think Louise Nevelson or Joseph Cornell were fueled by a search for it. Perhaps none of them, not one, really found it. Maybe because it was gone. Desire was contained, enclosed, shaped and commodified.

George Ault, in France.

I think an era of NSA surveillance, a normalizing of CCTV, or a security state that never shuts down, and of the constant ‘reality TV’ product, is one in which ‘looking’ is being replaced by being looked at. The machine is watching us. And the accepted authority of what are really very stupid writers on art and culture, from places are varied as Vanity Fair, and The New Yorker, to Artforum and more specialized journals of the fine arts, has left a profound hole where once curiosity lived. I feel this is a second generation without much curiosity. Or a dampened curiosity, and too much fear of authority. It feels as if there are more and more staggeringly bad professors.

As a small footnote to the last posting on MFA programs, I came across the blog Montevidayo, and a posting by “Johannes”.

He writes…

“I have written a lot about the prevalence of the rhetoric of “too much” in contemporary poetry. It is not surprising that it is critics like Steve Burt and Marjorie Perloff – critics who have actually ventured out of the ivory tower of academia to try to assess contemporary poetry – that have expressed this sentiment most consciously. They’ve seen the plague ground of the contemporary! But really, this rhetoric is incredibly pervasive in academia, and it’s just as pervasive among experimental or “avant-garde studies” professors as “traditionalist” professors.

The reason for this is very simple. Academia is based on the idea of “mastery” of a “field.” A “capacious” sense of the field, but mastery all the same (this is why the current incarnation of “the avant-garde” almost entirely coincides with the study of contemporary poetry, its’ a perfect fit, but more about that in a future post). In this case “the field of contemporary poetry.” To master this field, scholars need to have read the right texts (canonical poetry as well as secondary scholarship).

In some sense what scholars master is a “taste” – they learn to appreciate that Eliot – not say Harry Crosby – is a “major figure. They read a bunch of books that show why this is the case; they master a taste. Except, they don’t call it taste, because taste is not objective; taste is variable. So they say “this or that poet is major” or “important” – and the reason they can prove this is that he holds a certain place in the lineage of modern american poetry. I’m simplifying here quite a bit, but this basically is what’s going on.”

The interesting idea in this is “mastery”. And probably this is basically correct in that the complaints of ‘too much’ feel linked at their base with a Puritanism. That said, there are real questions connected to the volume of product. It is even more obvious, I suppose, in film. The practice of producing “artworks”: plays, poems, novels, movies, paintings, etc. is now generated by something previously not present. It is linked to this idea of the author and his or her brand. And more significantly, to the need for a continuing source of “new” material. The spring line. There must always be something new…even if its just repackaged. The mastery has clear echos of the instrumental, but also of conquest, and more, of making clear that the craft is the point. Its carpentry.

Watching Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring this week, I was also reminded of the debates in MFA programs on film. The need to justify the junk that one is fed. To justify propaganda. It reminded me of a student once, when I told him his film was just boring. And he said, “no I WANTED it to be boring”. See, sometimes having no talent is not enough, as Gore Vidal said of the Cockettes, though he might as well have said it of Ms Coppola. Sometimes there is nothing hidden. Sometimes there are no secrets.

Edward Biberman

An insightful post, John. I’m not familiar with the artists your mentioned, so it’s good to have a starting point. From a complete layman’s point of view, there is the emptiness in their work which is frightening, the weight of what isn’t there. It reminds of the travel posters of the 30’s, filtered through a nightmare, but instead of Marseille or Cannes or Lake Como, we’re off to Buffalo, Scranton, or Toledo.

And that’s a good point about canonical works, especially in cinema, which is easier for me to grasp because it’s a much younger art than poetry or painting. Terrible films are often considered classics because of when and where they were produced, while “minor” films are often overlooked. I know this is the case with Point Blank.

Great post. It seems like in this age where we get so bombarded with corporate images, which by their nature trains the viewer to see ONE message for every image, and one only… we’ve lost the ability to read between the lines, as it were, and see subtext.

Also agreed about the difference between Bouguereau and Courbet. A lot of Bouguereau is fluff, but then there are pieces such as the ones he painted of children… remarkable and uncanny. I like Courbet too, but you could argue a lot of his “iconoclasm” hasn’t aged well. Although I do love the Courbet painting you put in this post.

Yeah…in a sense both comments are saying much the same thing…and it revolves around what exir called the ‘training’ of vision. That training has as its baseline a marketed image. Now you attach a narrative to that trained expectation, or rather the narrative is built into it I think, and you see why certain pop culture conceits are now so entrenched. The emptiness is a powerful subtraction — and its not really emptiness per se. There are lots of banal images of deserted streets or empty beaches. Its not empty, its rather the construction of a loss, for lack of a better word. It is that sense of something having left…that should be there. And that is linked I believe to the basic trauma of childhood. And in this system where surveillance is now so normalized, i wonder if this specific emptiness isnt almost criminalized in a sense. Thats certainly my feeling.

Thanks for this blogpost, and for introducing me to George Ault’s paintings especially. Your blog is a continuing visual education. I had barely heard of most of the American painters you name here, and Ault was completely new to me.

Not-unrelated, I think: a contemporary English ‘realist’ painter whose work has fascinated me for years is George Shaw (shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2013), especially his series “‘Scenes From The Passion” and “The Sly and Unseen Day”:

https://www.google.de/search?q=george+shaw&espv=2&es_sm=93&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=1PUQU4H2BsqatQa4uoCIDg&ved=0CC4QsAQ&biw=1680&bih=945#q=george+shaw+scenes+from+the+passion&tbm=isch

No doubt some of the fascination has to do with the fact that we are near-contemporaries, and that I grew up in a very similar postwar-concrete working-class milieu.(I even used the same Humbrol model-paints as a kid, as did thousands of others.) Anyway, I find his work intensely evocative – but exactly what it evokes is almost impossible to name. Non-places and non-times, you could say. Blank moments of childhood. He makes the mundane numinous. (Sorry, I’m talking like a fanboy. Words are hard to find for these images. Somebody somewhere referred to Shaw’s paintings as “the stubbornly inarticulable residue” of his attempts at writing.)

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/video/2011/mar/09/george-shaw-baltic-video

thank you patrick. TERRIFIC stuff. Id not ever heard of shaw.