Praise

John, there’s a certain kind of art work I’ve been wanting to give public thanks for, and it’s a kind of work I associate with your plays generally – a work that’s defined by a fragmentary, elliptical quality that often gives it the sense of having happened by a kind of natural process rather than by an effort of will. In literature Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson is a great example, and so is Ondaatje’s The Collected Work of Billy the Kid. Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo is another example of this kind of wayward perfection – the lighting of a candle in a world that’s like a vast cathedral and somehow that candle is just enough to illuminate it perfectly. These works are so enjoyable because there’s so much aesthetic leverage involved – there’s a kind of absolute elegance, for example, in how Pedro Paramo articulates the complex state of mind of its time and place, and it’s so haunting as a result.

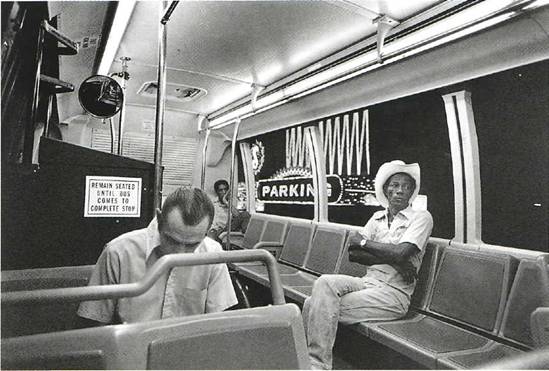

Bruno Schultz’s Street of Crocodiles has this feel to me too. Some of Kleist’s work. Isaac Babel has this quality, especially in the Red Cavalry stories, and maybe so does Robert Walser, though I suspect you’d finally have to qualify Walser differently. In theater I think of Buchner’s work – and especially Woyzeck – in this way. Also in some ways Kroetz’s plays. In cinema some of Val Lewton’s work has this kind of appeal and in a very different way so does a film like Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. You have a sense that the artist was working with an absolute purity of intention, on the edge of oblivion or perhaps having fully embraced the certainty that the work would never be known and yet somehow moving forward to complete it anyway simply for the expressive joy of the work itself. Authors mostly go on and screw up this legacy in an effort to repeat it. It may be the hardest kind of artistic success to repeat, and also the most alluring because it’s so pure. The purity is a problem because even wanting to repeat the success is a shame-inducing betrayal, and writers often die from the effects of being haunted by the memory of their earlier perfection. They anaesthetize themselves in various ways or actually protect their own work from future bastardizations and dilutions by taking their own life in some way – this may have happened to Sara Kane, for example.

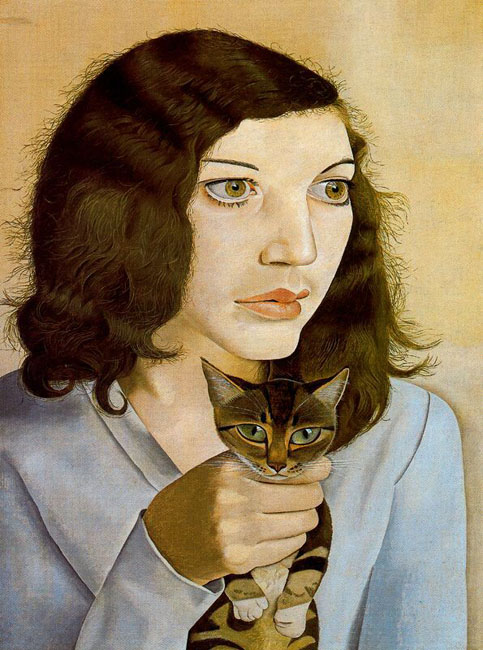

In this class of artwork there’s some link to the appeal of the fragment and the ruin that Benjamin articulates so well, and to the appeal of the pre-Socratic philosophers whose elaborate constructs Heidegger rebuilds from tiny fragments. But it’s not fragmentary work I’m talking about and it’s not what Deleuze and Guattari mean by Minor Literature either, though it’s positioned right next to both of these, I think. In painting I think of Phillip Guston and Chaim Soutine, though I’m not sure they’re quite the right examples – both too prominent, maybe. I do think this type of work exists in all the different forms. This is just one type of work I’d want to give thanks for, but it’s an interesting category and elusive really, what the qualities exactly are. Curious what this triggers in you and will have more to add depending on where the conversation goes…

Guy Z.

——————————–

Guy:

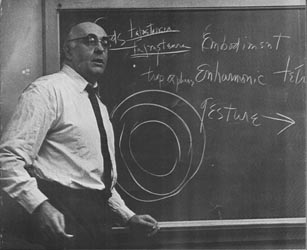

I’m so glad you mentioned Killer of Sheep, because it’s so perfect an example of so many different things. Its interesting to me, for last time I formally taught a class in writing, I used both the Ondaatje and Killer of Sheep, and later, Jesus’ Son. In all three cases there is a sense that narrative is being stretched beyond a place where it can bounce back… to disfigure a rubber band metaphor. Something else occurs to me here… in how we read artworks – literature or film or theatre, and that has to do with a sense of freshness, for lack of a better word. That this society reproduces itself – its marketed self and narrative – at an ever faster speed, has meant something to this elliptical form. Something is used up, and is digested – even structurally, and neutralized somehow. I think the mark (or one of them) of really major work is when it is able to resist this. Its partly just resisting a commodity form – in its essence (and Im on a slippery slope with that word I know). Maybe a simpler way of saying this is that its worth noting how things age. How artworks age. Pedro Paramo feels as fresh today as it did when it was written. It’s remarkably resistant to comparison and judgment. I am less sure if the Denis Johnson book does the same. I love that book and I love Johnson – but something doesn’t quite feel as sharp today when I read it. Same for Richard Ford – because those stories in Rock Springs are terrific. They also exhibit something of this elliptical quality, but there is a petrification going on there, a mannerism or posture that feels just a bit posed. In the Rulfo, what is alive remains alive. Now, this I believe has to do with the refusal of the author (in any medium) to demand the imposition of meaning. Of sovereign rule, of an insistence not just on “meaning”, but of form, or spirit – that the impulse to the mimetic here is only alive, when it separates itself from a rational (societal) demand to make sense. In other words when the inner logic is followed as it emerges, not as it thinks of itself as a coherent whole. Adorno says mimesis in art is the pre-spiritual. There is a tension, an opposition to ‘what is’, while at the same time helping reveal or helping to emerge that which ‘really’ is….or as Adorno says, the “most distantly archaic”. There is, at the end of this journey in the artwork, a reaching for reconciliation. It is never reached, however. This ‘impossibility’ is more acute in theatre I think. But however that may be, any narrative must work, in a processural way, toward its opposite. Spirit or spiritual must be concrete and the concrete must recognize its spirit.

Adorno said in Shoenberg, there remains the distant echo of the café fiddler. In Beckett this is obvious in the clown-show trope –which is never out of sight…and is, perhaps even, too obvious. All art is enigmatic. All narrative says something, and at the same moment conceals something else. Sometimes I think it conceals simultaneously that which it says. One might look at Pedro Paramo in this light. All of this is bound up with history. And because of this, it is impossibly complex. And because it is impossibly complex, it is a justification for its existence.

The processural – the journey – has become, as we inch forward further into the 21st century – ever more significant. The contained form has petrified. Containment as an aesthetic strategy is exhausted. The elliptical is one way out of this. Running concurrent with this fact is the impulse for understanding. Understanding itself has been colonized by the commodity form and a system of social domination. Even before that, however, understanding art has always been a trap.

For understanding, per se, begs questions of the consciousness embedded in the artwork. The truth of the enigma, or of the enigmatic-ness, is in opposition to understanding. The abuse of the enigmatic, and by extension, the artwork itself – the narrative – is done by those who imagine an expertise is required to nail down the meaning. A huge wound is torn open at the end of this failed operation, and an acute painful sense of insufficiency. This is where the truth of narrative and performance (in theatre) as a kind of thinking becomes very resonant.

It may be that greater artworks exceed their own understanding. Again, work that intentionally and self consciously look to be incomprehensible, are probably the most easily comprehended. The paradox of a Pound or William Carlos Williams, is that the ‘objective’ report (as Adorno put it) turns out not to be objective at all, and is actually a sabotage of reports in general. If one leaves the artwork (leaves the theatre – any theatre – even the theatre of painting or the story) with a comforting reassurance that what one saw and/or heard is understood, the residual sadness of this experience will gnaw away at the mimetic re-telling of it. When I put down Moby Dick or Pedro Paramo or The Sheltering Sky, all other issues aside, I am aware of my own psychic vertigo, which is both pleasurable and which, perhaps most significantly, expanding. That quality of spilling over the constructed walls of understanding is a radical awareness. It meets head on, often, the oppositional reading of the political or sociological. It is why a disturbing fascist such as Celine is alive – however repellant his ‘message’. And this is not to diminish the facts of his repulsive message, but that he may remain worth reading because that work defies its own construction. I think in Celine, the work stops short of real significance due to this, however. The message is too heavy, and it crushes the form in which we experience it. Now, I would say that (and I refer to Adorno yet again, here) that there is a distinction to be made between enigma and mystery. The enigma denies access to transcendent meaning. If the transcendent were available, even in a hidden or illegible form, the artwork would be a mystery that demanded de-coding. But the artwork denies this via its fracturedness (Adorno) – and as he said, Kafka made this a theme almost. The fractured quality is close to this idea of the elliptical. It is just a composition strategy finally. Again, the false elliptical is all too present in the self consciously obscure. A David Lynch, for example, simply trivializes the elliptical. The question is false, because there is no answer. In Kafka there is an answer, we just can’t get to it. There is no message in Lynch, but there is no question, either. In King Lear, there are questions, in fact so many questions that we are thrown back upon an almost delirious vertigo of plenitude. The narrative, the poetics, the procesurral truth – the journey – is indelible. And it carries into our sense of history and our formation of what is human.

Here is where that paradox of what is concrete becomes an issue again. The fracture is only a product of nature and history. That’s a loaded sentence, I know. This is where its genuine question to ask about integrity and the pandering to popularity and the commercial. Artistic integrity must be historical, and it must be concrete in a sense worth talking about further. Today, in advanced capital, both the left and right denounce artworks. In both cases it is a petit bourgeois desire for control – of message. Stay on message. The submission to the artwork relinquishes control, or the semblance of it. I think when you speak of artists working at the edge of oblivion, you touch upon this question of integrity. The sense that a work cannot be other than it is, is experienced as truth. This isn’t a lie, and that is what separates a Melville from a minor writer. No amount of kitsch parody can impinge on the veracity of Moby Dick. There is a different sort of historical mediation in all this, too. The missing voices in Conrad, or Dickens… doesn’t change the truth, but it does change the experience of that truth. The commodity form, reification, also impinges on modern and post modern work. The societal sense of impermanence in daily life cannot be washed away via a connaisseur-ship – an elitist reading that deconstructs the elements as a subservient homage to critical materialism. What is there is both there and not there. The artist’s integrity is going to cost him or her. Charles Burnett was not able to reproduce the wonder of Killer of Sheep, and some of this had to do with how capital mediates the film form. Part of it had to with more personal reasons, no doubt, but in any case he was a broken artist after that. The cult of genius is no doubt alive in this discussion, and perhaps the world cannot accommodate a Charles Olson any longer, or Patricia Highsmith (ironically) or Genet. I don’t know. The journey is now run at jet speed. At internet warp. And somewhere in this, in a loss of library visits and long sea voyages we have deformed our attention, appropriated it, and a tidal swell of cultural product in general has changed the terms of what form and structure mean. Genre becomes something other than it was. MFA writing programs are the final coffin nail on the sublime I suspect. But I will leave off here….back to you.

JS

————————————

John, I’m glad to see Patricia Highsmith’s name in your final paragraph, and PK Dick should probably be mentioned in the same context — as someone who happened to gather some integrity, or conjure it while at work in a commercial mode. Highsmith manages to be Dostoyevskian – which is to say metaphysical almost – in a similar kind of popular mode. Here we are describing a different sub-genre – those writers able to be subversive in a popular genre. Jim Thompson and Elmore Leonard come to mind as distant echoes here – Poe himself no doubt, along with Chesterton and even Robert Louis Stevenson and there are many others. Cormac McCarthy quite possibly belongs in this category, or at least has one foot firmly planted there.

What these writers share with the elliptical works we are looking at is a kind of degraded authorship, a sense that the work has simply manifested and the author, who may be celebrated in some way for the popularity of the work, is almost an after-thought. You can get to that place via commercial success, or from the other direction by way of the ruin, the fragment, the remnant. These are subtle distinctions, obviously, and it’s always so tricky to generalize and right now I’m writing now from within the spell of Bolano, who, like McCarthy, achieves something quite wonderful that crosses several of these boundaries – a kind of epic of the fragmentary. Somehow Savage Detectives, for example, seems to have something of Moby Dick in it – that epic fragmentation – but in the mode of a picaresque.

What I think is behind this discussion, ultimately, is the question of exactly what happens on the level of consciousness when the writer puts words on the page. The author is seeking to redeem language from all its encodings, the encodings of power and coercion and reductive identity through a singular act, a leap that involves a temporary self-absolution. The personal history, the weave of self-images, the private narratives and public investments of the author have to be cut away so that author can find his or her way to the place of immediate experience – what the Tibetans called “unborn awareness” – that will then, of course, end up reflecting and embodying all those layers of self-encoding, because, well, we’re made like that. If you’re a Deleuzian you’re okay with calling that awareness “desire”…but however you define it the reason it’s so valuable (which is another conversation, perhaps) is connected to the way that it’s so elusive and difficult to even recognize, and literary success only makes that act of recognition and that process of self-deconstruction that much more challenging. Freedom must be embraced despite the certain knowledge that freedom does not exist (at least not in anything but a spectral realm.) This is a paradox to be sure, and perhaps the only thing we can say is that the way in which that freedom does not exist is always different…and therefore interesting in a fugitive kind of way.

This is just another way of saying what you’ve said above, and I agree that the “reconciliation” of the art work is more challenging in theater than in the other literary modes. Also, possibly, more exciting when it does manage to take place. We are drawn to theater – to all art, really – because we are all engaged in a kind of inner nomadicization, a covert effort to deterritorialize ourselves before we are buried alive by the encodings of received (and therefore alienated) identity. This is where Celine’s success can be understood – his prose is struggling towards a freedom he doesn’t really believe in and, in fact, actively despises, and it gives the work a fascinating tension. For me Thomas Bernhard (who as everyone knows was heavily influenced by Celine) is even more intriguing along these same lines. I have more to say about this, but will close it here in the interest of the back and forth…

GZ

————————————-

Yeah:

love Highsmith, and in particular two books; The Tremor of Forgery and A Game For the Living. Both are books that come back to me, especially ‘Forgery, in a sort of haunting. It’s actually rather amazing how often that book will come to mind when I’m working on a new play or, really, anything. Highsmith was burdened, and still is, with the tag of being a ‘mystery’ writer and it’s a shame her work isn’t better appreciated at this point. She seemed to have this very acute, finely tuned sense of daily travel. She captured the seemingly banal movements of people — in a sense the same westerners who people Bowles work at times, and the anxiety that accompanied a trip to the corner store. She also realized the poetics of interiors. The personalities of rooms, big and small.

She wrote at much the same time as Dick, actually. I think the sixties arrived for certain sensibilities with a good deal of anxious but sensitized awareness of the subterranean currents that were shaping social unrest. Both were neurotically self lacerating and a bit paranoid –well, Dick was VERY paranoid. What’s interesting is that that period of post McCarthy fear and the end of the fifties can be seen as a cusp of something. You and I have talked a lot about the rise of marketing, but you can’t escape it, and it was certainly impactful as TV became a fixture, Nixon-Kennedy debated on TV, and Viet Nam was soon on TV. I think there was a lot of the changing of the guard in Academia, too. And there was the rise of MFA programs for fiction writers. The art world found itself at the end of several currents… the final, however mediated, gestures of the sincere, perhaps its romantic, I don’t know, in Abstract Expressionism, and the art market had begun its total domination of the artwork. Now, looking at work from the sixties, I think more than any other decade or two decades, perhaps, have artists in various fields, so changed in stature. I mean what seemed very relevant in 1964, rarely is what seems relevant now. I don’t know if that’s true of, say, the 1940s—and I think writers such as Highsmith, who stood outside the fashions of the moment, have endured far better than a John Barth for example.

Pynchon is a bit outside all this, although I’m not sure in what ways. I think I am trying to gain focus on the role of writing programs, of academia’s affect on cultural standards and how this intersected with the marketplace.

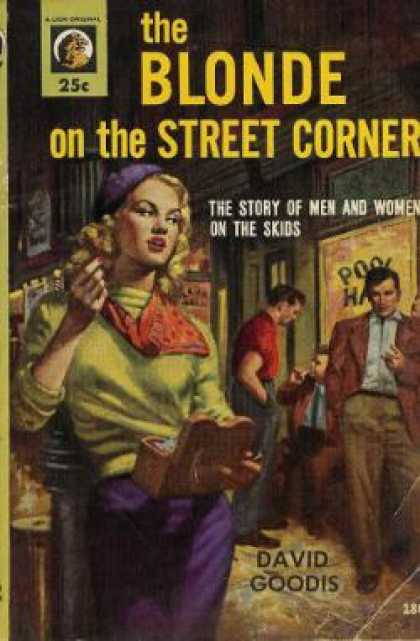

Today a writer from the thirties, like Cendrars, who is minor in anyway you approach him – seems fresh, though, and alive somehow, and it may be because that role, that calling, that idea of being an ‘artist’ is gone. Guys like Jim Thompson, who you mentioned, or David Goodis, or an Iceberg Slim, were a final call from the margins. Today, that call is bought and packaged so quickly, usually anyway, that it is rapidly assimilated by one or another specialized sub-phylum of writing or even performance. I am being very general here, but I think so many forces came together — over a period of thirty years, say, that changed the understanding the culture had of itself. The ironic was in ascendance, and coupled to the marketing forces at work infantilizing the culture, the result was a drastic increase in attenuated narrative forms and tropes – in melodrama and sentimental kitsch. And also, of course, in formula. I’m thinking, though, of the academic high brow culture as exists today. I mean in political commentary, too, in sports, in art and fiction — the mandate is attitude. Its posturing, it’s incoherent, but as long as its full of posing, and ‘tude and snarkiness, it finds a certain home. I had mentioned David Foster Wallace above… and I think he stands out as this voice of purity almost. His pain was clear in the face of things I suspect he felt culpable for. The most heinous post mortum on a writer ever written was that by Jonathan Franzen. And it so reeks of resentment and self loathing but it reinforces DFWs position as a sort of weird saint of the backward glance. The rear view mirror. I mean that in a highly positive sense. I think he suffered a world full of Franzens.

The pop art explosion of the sixties now seems almost embarrassing, if not quaint. I was in, I believe, New York a decade ago, at a museum, and it was probably the Modern, and I remember looking at a Morris Louis – a giant canvas, and it was a bit dirty…the untreated canvas Louis had stained was smudged. I’m not sure why this stuck with me, but it suggested an exact limit to Louis and lot of color field painters and in fact a lot of painting since. I’m not at all sure where I’m going with this, but I had wanted to touch on work that seems to be better now… minor but indelible like John Wilde for example – or major figures like Bacon or Kiefer. Something in the integrity of those images is clear. In writers, a Breece D’J Pancake, the truth being told is free of irony, so without attitude, that it is again, something akin to the monk or saint. It is prophecy.

I am reminded here of Auerbach’s well known opening chapter in Mimesis, in which he posits this split in western narrative between Homer and the Old Testament (of the King James). The externalized clear presentation of Homer, uniform, with unmistakably clear meanings attached to the behavior of the characters. In the Old Testament you have elliptical and unclear presentation, non-uniform, and with a greater influence on meaning by the unspoken and unpresented (the off stage), and with a deeper development and changes of the individual character. In other words, the development of the journey of the protagonist. Now, the thing that one should remember with work of this antiquity is that in reality we have no idea what it meant to its original audience. Narratives were news. Storytelling was, depending on the community and culture, a form of moral education, and of societal history. I suspect though, that narrative always, even from Homer through the late medieval societies, has had additional roles to play – it’s just we can’t interpret what it is. The truth content of an artwork, Adorno reminds us, is its greatest paradox. It is not something made, but exists within the extreme tensions of the work itself, and exists nowhere else than in what is made. What is made is, however, not the truth.

A final thought on Highsmith. I think you are right to bring up Dostoyevsky – and I guess it’s an obvious enough comparison on one level, but I think Highsmith can be compared to Camus as well, and she clearly drew on both in a way. There is something very ahead of its time in Highsmith. Something of the fragility of many young men in the US, that class of isolation and pitch of the lonely is realized so perfectly in Highsmith. I think because I have travelled so much alone over the years –on trains, buses, across Europe, mostly – I feel something in Highsmith that knows that lonely crowd, the impersonal room of an acquaintance. Rooms in which the unfamiliar extends even to language. Public room, private, and always a bit unfamiliar. Even the rooms of friends tend toward the opaque in Highsmith. There is something unsettling, always, in her landscapes. Her biographer, Joan Shenkar, said if Highsmith had not become a writer, she would have been a murderer. I suspect that is probably close to the truth. The crime, the criminal, is in Highsmith the author herself.

Now, I wanted, in this light, to touch on one other aspect of narrative – artworks are good or not good because of the form, the procedure, not because of what the author thinks about them. The particular form expressionism took in modern art was the spectre of the patriarch. The reactionary tendency in writers like Franzen or Houellebecq is really the defensiveness of those dominated by the super ego – the resentful who chafe at disturbances to the status quo. In them, the patriarchal is weak and impotent, and in a way I think this accounts for their popularity. It is a narrative of dryness, of sterility, and the excesses are faux excesses. There is a sense of gloved hands, germ free, that then dabble carefully in the crime.

This leads to large questions about the evolution of ‘inwardness’ in narrative. It also raises questions about how this differs in performance on stage. It also raises issues about the ideological dimension of inwardness – the obedient worker, the compliant and ever more powerless laborer. We can go back to Luther, and the Reformation, and see in Kierkegaard, and we fast forward to the gradual but inevitable erasure of the inward. I think narrative, and the mimetic, cannot find traction when the weakened ego of conformist capital dominates and so the Lacanian criminal –the individual’s Oedipal narrative becomes ideological somehow, and a David Foster Wallace in his inherent honesty, existed in that place, that space, in the shadow of reification and commodity which became (per Adorno) a weeping without tears. His was the most authentic confession possible, in the terms of the novel.

I shall hand this back to you now….JS

———————————-

John, the writing programs sprang up to sustain the production of literature when the market for it had collapsed. It was no longer possible to support oneself as a writer by selling books to a readership, so writers needed to become teachers of writing, and readership has now become this odd sort of cultural assignment rigged up by those in charge of cultural production. Do you know what I mean? The NY Times compiles its best seller list and there’s a certain percentage of the population that is going to take that seriously and seek to read it all and tick off each of the entries and talk about it at the beach or in passing at the cocktail party…but that’s a whole different thing than the readership of a Dickens or a Balzac or a Victor Hugo who thronged the streets when the author died in order to pay their respects. Those huge figures supported the cultural economy that also produced Kafkas and Joyces and Prousts, etc. but now all we get is Jonathan Franzen who, I completely agree, is the biggest literary zombie of them all. Good lord his writing depresses me and is insufferable – a single line of Franzen’s will send me into despair, so intricate is the weave of bad-faith there. His correlate in theater is, of course, Neil LaBute, whose work I am always attempting to find something good to say about because he’s not really worth the breath it takes to denounce him. But wait a minute, we are here to praise, so forget those guys. It’s Bolano’s fault – he’s so refreshingly unrestrained in his denunciations.

Highsmith and Bowles – yes, indeed they are quite similar in many ways. I always think Bowles betrayed himself when he strayed too far in the direction of existential philosophy, as he did in some places in The Sheltering Sky, and quite a bit in some of his other novels, particularly Let it Come Down and The Spider’s House. His stories, many of them anyway, are gems and they hold onto a genre delivery – they want to belong to a world where Rider Haggard is being read, or Lawrence Durrell, or, for that matter, Hemmingway. Camus is probably the exact pivot his work shares with Highsmith, though with Bowles the link has really to do with tone – that scopic clarity he has that is very Camus-like. What I think Highsmith shares with Camus is the uncanniness of the double, and that’s what points to Dostoyevski and, obviously, to Rene Girard. Bowles’ work doesn’t really traffic in the uncanny in that way – his tourists are often victims, but never sacrificial victims. Highsmith seems to have understood the abject quality of the double and of triangular desire – that we seek to ground ourselves or become ourselves – achieve some sort of solidity – by imitating the desire of the other, and the modern economy is entirely driven by this kind of covert, pointless farce, which one can only chuckle about if one is willing to ignore all the very real suffering – the despoiled ecosystems, the wars, the exploitative debt-structures – that supports it. This is what you are pointing at with your comments about the Oedipalization of the individual – Highsmith’s character Ripley is the embodiment of our moral degradation, and Highsmith served him up to us with a smile and took her big check to the bank and had a stiff drink. You mention David Foster Wallace, who I’ve always found annoying, but I suspect you’re right that he saw what we’re describing, and eventually took his own life out of despair from it, and also, like Jackson Pollak, out of a kind of shame about his own complicity with this colossus of bad faith, a complicity based on the kind of fake literary celebrity we’re touching on here.

And, yes, I agree with you about the source of all this in the Reformation, which revealed the emptiness of all social and psychological constructs but still left us culturally in opposition to that emptiness. Here, of course, is the great appeal of dharma and the Eastern views in which that emptiness is embraced rather than anathamized. To me, the history of Western culture from the Romantics forward can best be understood as a covert Tantric lineage that doesn’t even recognize itself as it painfully locates the very paradoxical ground (lack of ground, actually) of our being. The double is uncanny – and also sacred – because the double underscores our unescapeably emergent aspect which, with sufficient courage, we can come to celebrate as plenitude rather than demonize as lack. This, of course, is where I part company with Lacan, who defined with great clarity the trap of (Oedipal) identity without allowing for a relationship with experience unmediated by identity, which is always reductive. What else was Proust describing? Or Buchner or Kleist? Or, in his own very different way, Beckett?

Here’s the thing: a writer must always write from an identity, but that identity is never real, and the way that paradox registers depends on the level of authenticity required by the literary form. Someone like Highsmith is working in a form that does not really require much authenticity – the reader wants to know “what happens next” and the overriding intention is to sweep the reader along on a convincing plot or narrative – so she can make her points about triangular desire in a more or less breezy way. Beckett is down in the mud wrestling with the angel of authenticity – with how deeply we crave it and how it continually eludes us – and so the paradox costs him a great deal, and as a result the work is very rich in transformative moxie.

But then, as Beckett wrote, the market fell away – the public stopped really reading. The great oil-rich sensorium of the Post War American boom let everyone off the hook by providing endless distractions and palliatives, and to support the activity of literature we need writing programs and everyone wants to discover their “inner writer,” a triangular construction if there ever was one. As Artaud put it, writing about Van Gogh: “No one has ever written, painted, sculpted, modeled, built, or invented except literally to get out of hell.” Well, maybe everyone is kind of in “hell” – the Buddhists certainly think so – so there’s nothing wrong with this…but there’s no reason we should tolerate the masquerade of a Franzen, the ridiculous posturing of the literary genius of our age supported by torturously constructed and executed pastiches of “great” middle-brow writers of yesterday. I mean, whatever happened to “make it new?” (And let me be quick to absolve poor Jonathan on a personal level because he actually just availed himself of trends that were at work in the environment in which he was operating in.) But how do these guys go about there bullshit as if Kafka, Joyce and Beckett never existed? Is it all Raymond Carver’s fault? I love Carver, and you always knew reading him that he had read his Kafka and had respect for that achievement, and was simply opting for the kind of effect that was available to him, and that was similar in a way to what Highsmith achieved, but in a more Chekhovian vein…Whoops, I’m at it again. Back to you, sir.

GZ

———————————————–

I agree about writing programs…and additionally, they are there to reproduce the domesticated voices of the status quo. The more educated liberal audience finds justification for their existence, by being flattered that the NY Times and wherever makes a list that tells them ‘who’ to read to be hip and cultured. They also create the readership for this affluent class. All of this, of course, is western, and to that degree privileged.

It also serves the purpose (such is the cunning of capital) to marginalize further those voices outside this system. Young radical voices are more likely to end up writing screenplays than fiction these days. Even fewer turn to theatre…because, I mean, why would you? In a culture that validates a LeBute or a Franzen, it’s not hard to see the logic at work. LeBute is the perfect creation of the system. He is reactionary by default, he is middle brow in his taste (or lack of it) and he just offensive enough to create titters and hand wringing and mild condemnation. He makes a fortune at being half bad, half mediocre.

The role fiction or theatre plays in the culture is very interesting – at this point. Theatre retains a radicalness, in spite of everything, because it is still civic on some impoverished level, and cheap to produce. To be published now means you must go to an MFA program and jump through various hoops and get book blurbs from your professor, and crank out your first novel…usually quickly remaindered. Some move forward, the Franzens, and then there is the whole Dave Eggers phenomenon etc. But it is, in general, a seamless system of reproducing the same.

The thing is, with Wallace, he did bear witness to his own entrapment. And he explored that psychic wound pretty deeply. Obviously, at great cost. Now, I want to add that I think Highsmith steps beyond the surface conventions under which she writes…and really, I’m not convinced a novel like The Tremor of Forgery is even a crime novel per se. She was extending the form to a place where it ceased to have its original meaning. Again, writers such as David Goodis and Jim Thompson have only with time come to seem important. And in the case of Goodis, it’s more the entire oeuvre, the entire project, that accumulates as one long meditation on failure and pessimism. The late books, with Philadelphia as a back drop, are as hopeless and despairing as any in American fiction. My question is, what and how does writing acquire meaning now? This is, yes, still a pretty small audience … but then I would still like to believe that there is an alchemical process by which utterance and the writing of words on a page, can accrue to awakening for this small class of attentive reader. And it’s smaller than ever. It’s a remote priest class of readers – and that is the true change from sixty years , or even fifty years ago. A Hemingway or Faulkner were still defining coherence, morally, spiritually, and at a community level even, creating a world one might enter and reflect upon …and were best sellers. What Hemingway said meant something. What Dickens said, meant something. Now, in a different sense, what Burroughs said, also meant something. I feel as if he was among the final radical voices to produce a consistent body of work whose veracity – whose demands – couldn’t really be denied. Some poets perhaps, came later… a few. James Wright, perhaps. The point is, however, that even in Europe and South America certainly, the writer/artist maintained traction, until very recently. And maybe to a degree, a small degree, even now. I don’t think so much in the US. The sheer size of the spectacle just washes over things and digests them and spews them back out as wallpaper or ad copy or TV cop drama.

What will be the fate of Cormac McCarthy?

There are costs, I actually believe that, for example, film stars, celebrities, who have their photo taken jillions of times, eventually see their face disappear. Literally, the face is used up. It’s NOT our familiarity with the face, it’s their actual face that starts to wear down. Jack Nicholson comes to mind. So it is with fame. And the artist who refuses nothing –Franzan or LeBute – the unrefusing hacks of culture, the cultural jackals, eventually die before us, spiritual executions, spiritual self-immolation –and this is partly why your comments on the ‘double’ are worth talking about more.

Adorno said whoever concretely enjoys artworks is a philistine. Also that the more the artwork is understood the less it is enjoyed. That second statement is very dialectical and really, it goes directly to the specificity of the artwork. Its (arts) very justification is predicated on the specific qualities and forms each work contains. The 21st century consumer consciousness wants art to be a distraction. And temporary. Reified consciousness only suffers anxiety in the face of that narrative which does not reinforce the rightness of his (even temporary) possession of it.

There remains too much fear in Kafka for him to be made into a TV series. Still the seduction of large payment for artistic creation is irresistible. It is, and it can’t not be. The trick is to create what cannot be so effortlessly co-opted. Now, the image of beauty, and of the ugly, raises itself here – and the ugly cannot be explained in formal terms, anymore than the beautiful can. The ugly is the remnant of violence. The industrial landscape, factory towns and the overflowing sewage that litters its street –that is ugly, but it is the tracings of violence. However, the bourgeois consciousness, the liberal commodity consumer, in his or her ranting against this ugliness betrays something of its own ideological bad faith. For it is usually, “how dare you SHOW me this ugliness”.

I think that I am circling around questions too complex for this dialogue —so I will return to a couple writers worth noting, especially in light of Dostoyevsky and the Double. One is Thomas Bernhard, and the other is Ryszard Kapuscinski. Both seem to me important because they are blowing up form, but not conceptually, but rather formally, as an organic growth. They come to the truth from polar extremes, actually. Kapuscinski may not have been a great writer, or thinker, but he was a witness, and a reliable one. In his sober compassion there is something that renders him hard to argue against. In another sense so is V.S. Naipaul, my favorite reactionary. Naipual’s fiction is of little interest, but his non-fiction is highly important. So is Kapuscinski’s. Bernhard is, I think, one of the final voices of a rarified sensibility, an elite technician of spiritual truths. What you wrote above regarding the Double, finds its expression more in the journalistic writings of a Kapucsinski, than in MFA graduates. For in the non-fiction of Kapuscinksi, what is always emergent is the ‘real’ landscape, the ‘real’ as it must be, and while this isn’t sacrifice per se, it is in a de-facto sort of way. The people wandering the lobby of the Zanzibar Hotel, or the streets of Salvador, or the train station in Dakar, become undeniable personages in a new cosmic drama. Naipaul’s three books on India, and his essays on the Caribbean, haunt one in exactly the same way. For Naipaul, there is an added awareness of history that is embedded in the Amer-Indian foundation bricks now laid over with cheap watered down concrete in a store in Trinidad. These figures in the landscape demand answers from the agents of un-freedom, the consumer culture of the west. There is a complex negation of the subjective going on here.

I will leave off now, with the hope of talking about Bernhard more. Both in his novels but maybe more even in his plays, he is the Francis Bacon of the linguistic narrative. The Kiefer of prose or theatre narrative.

JS

————————————–

John, it’s interesting you mention Kapuscinski because The Savage Detectives closes with

a section that takes place among journalists in Africa that read like an homage to his work.

Bolano is a writer who seems tailor made for this discussion – working very much within

the nomadic vein I think we’re skirting or touching on here. His work is biographical in the

way that Bernhard is biographical, interestingly enough, but that fabulist energy of Latin

American literature has morphed into something closely linked to desire, but desire in

a mode that assumes the self is already a ruin, an uninhabitable structure that needs to

be abandoned the way a story is abandoned as it is told. Interestingly also both authors,

Bernhard and Bolano, were writing under a medially imposed death sentence – the certainty

of a premature death – as was, of course, Chekhov. The way literary activity relates to our

experience of mortality is obviously very much in play here, clearly. I always feel Bernhard

is going straight there – straight into the certainty of his dying – when he writes, and going

along with him is oddly reassuring. He is working under a weight we don’t like to imagine

ourselves shouldering even though we know we inevitably must. And it gives Bernhard that

wonderful irreverent crankiness – that cussedness and that ability to fully embrace the most

abject aspects of being human – the insane ill-will we bear each other in the depths of our

muttering hearts. Bernhard has no where to turn and so he blurts out the truth as if it might

buy him some breathing room and maybe it does for a bit and then he has to blurt it out

again and there’s a desperate quality that is amusing and touching all at the same time. I like

your comparison to Francis Bacon, whose paintings feel like the other side of his own flayed

hide, as if he were expanding on Michelangelo’s flayed skin held by Christ in the Sistene

Chapel. These guys both understand how art has to wound you in order to be art, and the

artist has to work out of that wound too, authentically and without pride and the desire to

be popular or well-loved is a significant obstacle to real work. Sadly enough.

This is already fairly long so I don’t want to keep flogging…except to underscore the

connection you’re making between the production of art and the contemporary political

culture and the issues of alienated consciousness. It is Adorno’s great subject and it

suddenly seems striking to me that artists for the most part absolve themselves of the

need to examine what they are doing in that light. I’m struck that this little dialogue seems

conspicuous in that regard – one of the few places one might find that connection being

made. This might in part be because of how traumatized artists always are – the need

to accent the positive rather than highlight the way artistic production is supporting the

advance of neoliberal capitalism – the sucking dry of everything with value. One of the

advantages of a Deleuzian framework in this context is that, rather than being some alien

takeover, this nightmarish dynamic is actually itself an expression of desire, of the constant

encoding and de-coding of desire-production. The remedy lies in the kind of nomadicization

literary works like Pedro Paramo and Thomas Bernhard’s Gargoyles express and help inspire

– the recognition that the human species was always going to back itself into this corner and

the only real question now is whether or not the human species can find a way out.

GZ

“As the negation of the absolute idea, content can no longer be identified with reason as it is postulated by idealism; content has become the critique of the omnipotence of reason, and it can therefore no longer be reasonable according to the norms set by discursive thought” Adorno

I think one thing we have pointed at, without talking about directly, is the blockage of tradition, its terminus. This runs alongside the elevation of the fragment and of “works in progress”…and a host of other appropriations of modernist strategy by the post modern (usually thinking the ideas are new). These movements in form and the structural adjustments have accelerated as western society hurtles toward the gaping mouth of oblivion. However, I think that with so much cheapened, so much ersatz experience for sale, that even ideas of pleasure take on the aspect of work. I am suspicious of the word whenever I hear it, actually.

Are we having fun yet? Well, I didn’t know when I was six, and I don’t know now. I certainly recognize the sublime and whether I attach enjoyment to it, or not, hardly matters. I suspect there are two prongs for artists looking ahead. One is the assault on the commodity, on kitsch, and on academia. The other is a restocked resistance to the false spiritual. They overlap of course, but it’s important to articulate them. The best prose of the 20th century may well have been found in Broch’s Death of Virgil. I think of Broch and of Bernhard, for they contain something similar. A northern-ness maybe, and the German language of course. The durability and duration of those writers who insist on subtracting the kitsch and sales receipts, the narcissistic and the language of accountants , they emerge and there are usually few doubts, really, eventually, about who they are.

JS

Guy Zimmerman has served as Artistic Director of Padua Playwrights since 2001, staging over thirty five productions of new work including new plays by John Steppling, Murray Mednick, Rita Valencia and others. A playwright and director, his plays include Vagrant, The Inside Job, and, currently featured in the Hollywood Fringe Festival, The Black Glass. His film work includes the shorts Pronghorn and Great Things (also in this year’s Fringe) and the soon-to-be-released independent feature Gary’s Walk starring John Diehl and based on the play by Murray Mednick. He’s currently completing his Phd in Theater and Drama and UC Irvine.

I have to let my brain get over the shock of the harmony of Chen and Ruisdale, so just prelim thanks for posting this. The vision of the candle is very evocative and clarifying.

And I see why Pynchon doesn’t fit though Moby Dick does but the hardboiled stuff seems to me in the closed work pile including Highsmith. Perhaps Bolano, whom I have not read, is the kjey piece that makes this collection make sense.

I feel as one should respond with a proposed list for inclusion. (Karl Kraus, Georg Perec, Italo Calvino?) And projects/movements (Oulipo has something to do with a search for method for this?)

“We can go back to Luther, and the Reformation, and see in Kierkegaard, and we fast forward to the gradual but inevitable erasure of the inward.”

In some way Oulipo and similar were trying to revive the querelle of free will in a kind of clunky Luther – Erasmus format, but having shelved an actual divine and centred (a specific figure of) the artists solely as creator and not at all as created or determined, just a rival of the rules or the arbitrary or the structure or whatever – the rival demiurges, artist and something. The best writers took up the task of demonstrating some dialectical process through this but its not fruitful really. What cannot be retrieved by these modernists is the assumption of the social even in the (then) radical interiority of earth protestants and isolated relation of soul to God. Luther and Erasmus couldn’t dream of the isolation of great eerie hardboiled writers (not Hammett not really Chandler but the others, Cain, Goodis, Woolrich.)

The misogyny that holds the hardboiled and noir together – and great woman author Highsmith very much included — hints at the real basis of this beyond-Calvinist isolation, if we want to historicise the pop psychoanalysis of this popular/mass (national popular but imperial American?) culture (noir, hardboiled).

On the cultural decline front…yes Franzen is all you say but that much differently than Dickens was. And he is the product of big media. But as Dickens wasn’t the summit of novelistic art in the mid 19th century Britain, Franzen is not all we get. The form has been surpassed in importance this hundred years but its not like there isn’t a lot of wonderful writing in it still. We get some terrific novelists in this dying form…just from NY: Sarah Schulman, Rivka Galchen, Jennifer Egan, Sheri Holman…

You’ll enjoy this by the way:

Anya Ulinich:

http://www.pen.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/2812/prmID/1502

Plenty of authors standing against the hideous fraudulent celebrated upper ranks of lethem, foster wallace, jonathan safran foer, nicole krauss, zadie smith etc. They don’t get the sales of that rank but they’re not simply obscure either.

Ha, yeah, I love both Chen and Ruisdale….the latter is kinda very neglected. Anyway…..there is a lot to say, a ton to say about goodis, cain, woolrich group..and thompson. I mean thompson is the best known, possibly, and the least interesting finally. But there is a LOT to say about them all. Msyogny and just nihilism…..this mysanthropic writing that becomes so other than what it seems….except perhaps for thompson, who IS what he seems i feel. Goodis is by far the most extreme nihilist….but he grasps the utter alienation of a working class adrift in these soiled cities. His fear of women, hatred of women….he had left hollywood after not doing very well as a screenwriter. The bigger issue, and one worth writing about, is the assumption of the social…..as it was handed down and then Highsmith….who i really rate very highly. Tremor of Forgery is among my very favorite novels ever. But the luther -reformation construct…itself a reaction…..is a great topic and an approach not often explored.

I am going to steadfastly defend wallace. Im surprised he isnt defended, actually. But sure……sarah shulman i love…AND we’re facebook friends. There are terrific writers out there…mathew f Jones, and denis johnson, but that wasnt really the point. The point actually was the marketed concensus on this stuff…………and the insane sort of economic hegemony enforced via MFA programs…which by the way is true in theatre as well. You dont get done in mid or large houses if you havent gone to yale or Carnegie mellon or berkely or cal arts or whateverthefuckever other U. has a big program. Another very good writer is alan heathcock, who is a sort of rocky mountain breece pancake. The other aspect, which is why it came up at all, is the critical collusion with this………safron , zadie et al are unreadable……its not even as good as an episode of Greys Anatomy……its just utter word virus. BUT…..there is a sort of contagion to this. BECAUSE of the MFA programs, because of the NYTImes and NYRB and all the rest, the New Yorker, etc…because of that the normal cultural photosynthesis is halted — Franzen is like monsanto GM suicide seeds…..it disrupts the normal cross polination — and in a sense a lot of work now reflects a strange isolation –and as I sit here thinking on this, it may be that the Goodis Cain nexus prefigured this isolation, the marginalizing of those outside the academy (by extension the media outlets etc……..) and i suspect the ways in which genre has grown….sci fi in particular…..with its specialized fan base ( i mean i know some smart people who take samuel delaney seriously) and specialized set of norms for this specialized appreciation………..one which is by definition almost cut off from daily life, from class struggle, etc. The writers you mention, and i mention…shulman and Jones and whoever….denis johnson……..all have strong connection with community life and with the underclass. Thats one clear demarcation. Franzen doesnt…..last poor person he met he gave a nickel to……..or someone like eddie bunker….I mean when you read Bunker you cannot help but feel some of life you got in a Cendrars. Eddie was minor, but very good minor. The other factor the media and marketing do is to constantly vigilently spy on underclass fashions……and appropriate them. < The best of the new writing is, then, by neccessity, made to step further and further away from what they critique, in form AND in the narrative metaphysics, if you will. But yes, and i never meant to suggest there wasnt good writing. But its far less visible than Faulker or hemingway were.

I’ve read Smith and Franzen and I don’t think they are that poisonous. They are television. Jodi Picoult and some other bestsellers noted the super hype and respect Franzen got…and rightly recognized his work as pretty close to what she does. He gets respect because a) he’s a man and b) he’s not writing about ghouls like Stephen King. But The Corrections was a very satisfying work for someone who reads Jodi Picoult or the like. I don’t think contempt for that is appropriuare just because its print instead of tv. If that stuff was on HBO people would be falling over in admiration.

Zadie Smith started out kind of interesting with a book that was the sort that normally ends in a drawer. By accident her first novel ended published and hyped. It was pretty good for a first novel, someone so young. There were all the usual flaws of the egotism and imitation of a writer that age, but there was also an expansive loving sensibility and sense of humour and compelling characters. I read it in two days. Then due I think to her experience as this hyped novelist she became pretentious crap. Her criticism is worse than hipster fogey, it is loathesomely reactionary. (I say this as someone who shares her taste – I love George Eliot and E M Forster etc). But the hype and backlash is standard for young women…remember what was done to Tama Janowitz after the success of Slaves of New York (mediocre, a bit reactionary in ideas about gender, much like White Teeth). As if either of them had claimed to be Great, they were punished for the lavish exaggerated praise they’d initially received. These were judgements critics made for their own purposes, and then the backlash and repudiation, as extreme, as baseless, was also for the purposes of the auxilliary production. The kinds of abuse heaped on them is very gendered.

Do you remember Arthur Miller said people always ask where is the great broadway play today? and he said well how about asking where’s a pretty good broadway play? Because one needs a lot of pretty good plays.

Now Jonathan Safran Foer and Nicole Krauss are odious, disgusting. Franzen and Smith are just unjustly revered above their peers like Jodi Picoult, Susan Isaacs, and the like. They have some features that guarantee their classification as literary fiction rather than genre or simply fiction, but it’s very superficial. Some of these ghettoized “women’s fiction” and romance writers really *write* well,n trnasparently, making books that are low tech films or soap operas. And that is what Franzen is too.

DFW. Well, I think he’s grossly overrated, with this showy superficial ‘brightness”. And I did read Infinite Jest and some of it was funny but its just this display of entitlement based on the trappings of class stature and education that has no gravity or consequences.

I think DFW is a good deal more than that. And a great essayist as well….his small pieces on tennis are pretty great. I dont fault him for being a white guy from an affluent background. And he certainly is of an entirely different order than franzen or zadie. I would argue both ARE odious. Smith’s book , that first novel, was just drivel….just sort of vapid empty drivel. Jonathan safron Foer is, yes, odious. I think as i wrote about Houllebecq, there is something worth analysing in the popularity. They were annointed for a reason……..and its not only that they on the surface reflect certain values and recieved wisdom…..its also in the DNA of their language. Its a big topic……and maybe worth writing more about. (in fact i think i will). Sometimes one has to look at the marketing a bit seperately, at first, and see whats really there. > The nature of the prose in a franzen , the world he creates…assumes…..and in this way he reminds of that creep Amis……its a world of snarky assumption masquerading as insight. —Women’s fiction is a big niche of the market, actually. Women writers around the age of thirty are the most published, in terms of first novels, than any other demographic. Of course, that assumes they write the ‘right’ kind of book. — I think miller is barely worth quoting ever, personally. And broadway and blah blah…i dont care and it means nothing in terms of theatre, anyway. it never has. The real topic here is , in my opinion, the narrative as its constructed by the likes of franzen…..or any of the rest…….Safron fr…….that it is a reaction to something as well as an establishing of a discourse that declares its value as foundational prose for its generation.

DFW…I think his stuff is cheap actually. the stuff on tennis was just cheap pleasures for a certain audience. Yes he has a facility but it’s vacuous, or worse, as with his paen to John McCain. From edssays I expect more than facile writing – one has to think well too. DFW doesn’t think at all; he spouts clichés with the conviction of his own brightness and originality. But there is also the psychic pain there…as his William Safirism exhibited. He should be bright enough to know that “could care less” is SARCASTIC, like “fat chance”. But that would be too “‘ethnic” or “tribal” (“could care less” is originally Italo-American, like “oh that’s beautiful” to mean “what a catastrophe” and “I trust you implicitly”‘ to mean “you lying fuck.”) for him to accept, so he just decides it’s “wrong”. I don’t fault him for being a white guy from an affluent background – some of my favourite writers are to be sure! – though his having this as a gripe is unattractive (it’s not so much the problem with his novels). But I think his celebrity and his style is 100% expression of privilege. He is not that good a writer. His thinking is adolescent. All the factoids don’t profundity make. He’s trying very hard to please and impress. I don’t like Lorrie Moore or Rick Moody or A M Homes any better really but at least their prose doesn’t keep poking you in the sternum.

Yes women”s fiction is huge. And women do most of the reading and book buying so no surprise there. But Picoult was pointing out that Franzen writes in basically her genre, or that of women’s fiction, Susan Isaacs, Jennifer Weiner…books about (white, middle class) families, relationships. Sagas.

Yet the Franzen hype hardly even made an effort to fool you into thinking it serious or sincere. Nobody really thought that much of his work. All these controversies provoked by James Wood are so stilted and plainly cynical, an effort to revive a kind of discourse that just doesn’t exist anymore, the world of the Shawn New Yorker. It’s the same kind of nostalgia as the new deal nostalgia that doesn’t want to face the golden age’s reality of patriarchy and lynching and imperialism etc.. But it is not even careful to disguise its posturing and commercialism.

Rivka Galchen wrote an essay on Walser that I think performed this kind of nostalgia for a kind of love for and attention to Significant Literature in a way that at once confessed and forgave it’s obsolescence and posturing. But look at this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RS2M53AKP8E

The body language, the demeanor, is so self-effacing its painful. the upspeak, the lowered heads, the histrionic nerdiness and hesitancy. This has the backlash against feminism all over it. And with Zadie Smith all these young women are seeking to conjure through their gestures and performed fantasies a world of “culture” that simply no longer exists.

DFW went yaddayaddayadda and did his persona so assured that watching him talk you would think there was a world where his books mattered to culture workers the way Goodbye Columbus once mattered.

childishness as shield against abusive criticism:

http://youtu.be/D5rb6J-8Fwk

http://youtu.be/B-KsMUHXaVE

compare

http://youtu.be/ink55hpRzEw

http://youtu.be/8BwxgXrQ5gI

Well, you find it cliched. I dont. Nor do I find it the least, not the LEAST bit trivial…..so I suspect (from my pov) you just miss a whole big chunk of what is going on. But thats just my take. “cheap pleasures” for a certain audience…..well….. I dont even know quite what that means. I certainly didn’t find it cheap. I dont follow the logic in there. But taste is taste…..the thing with Wallace is that he wrote from a real intelligence, not a postured fake intelect like franzen…hence the latter’s resentment. I think his best work is probably, in the end, not major….but its simply so clearly superior to most of what passes for po mo fiction that I cant think what else to say. I sort of don’t have the energy to defend DFW. I think he was a genuine, and smart, and actually rather insightful…. in a way that resonantes with a disturbing sort of clarity, actually. But like i say, IM NOT going to spend tons of time defending him. You dont like him, so stipulated. ¨¨¨

I think i would disagree to an extent about Franzen not trying to fool you. I think thats actually largely what he did. In fact its all he did, really. He just did in several registers at different times….but his project is to install himself as voice of a generation. He is the most welcoming hack I can think of in terms of adulation……yes yes, true, true……more more.

the faux art wars of James Wood and his like, are both ersatz and real. The content is manufactured to the extent that what is being argued over is all the same. But the wars on another levell reflect the economic wars of “prestige” art, etc. And yeah, they’d love to restore some sense of authenticity to what they are yabbering away about. But I mean its funny, because every time I read wood or those like him I am struck by the fact that they say the SAME THING every single time….about every single author or artist they focus on. Its like the weather report on TV in London…..cloudy, overcast, drizzle, with a high of fourteen. EVERY DAY….july to dec. Thats what this elite glossy shit reads like…..utterly endlessly repetitive. Joan Acocella, Gladwell, all these people. Its the middle mind. Acocella just had a retarded thing this week on Grimm’s fairy Tales….and it is so revealing. The darkness of childhood never reached joan. And it never reaches gladwell or any of these people…..certainly not Franzen or Foer. As for Zadie Smith………….i mean, ok, solidarity with your sisters and all that…..but she is a shit writer. Simply the MOST trivial sort of nothing. She was attractive and bi-facial and had a brit accent…PERFECT. marketer’s dream. And thats what it call comes down to, finally. I mean we can debate the relative merits of DFW or smith….or whoever is du jour……………but the issue is this structural stranglehold that has infected discourse. You or I or my friends may know this or that writer we think good……who sells ten books probably. And maybe, if lucky, teaches at Wabash Community college….or Fresno State…..and that is its own topic. The critical – academic mafia though, corporate and middle brow and hygenic….has served to create a edifice, culturally, that is part of larger corporate domination……and while Im here….what IS women’s fiction? thats a genre?? I remember when i started to see James baldwin in GAY LIT sections of bookstores. – oh, and rick moody .. god, he’s a perfect sort of example of mock serious masculinist jerk off writing. It is SO empty……so yeah, so empty as to make zadie appear as tolstoy. If you want to throw down on who is THEE worst of the well respected literati at the moment…id pick moody. (there is a lurking side bar discussion to be had on this, vis a vis DeLillo….who i dont like at all….but who i find a lot of smart people I know continuing to rave about. )

By cheap I mean easy lighting up of affect – we all bond with the writer and assumed readers with statements like the hyperbolic expressions of joy in watching the extraordinary athlete do something that seems impossible. We all know that feeling, sitting in the stadium, Shea perhaps, Doc Gooden, and the guy behind you says “I think that one went into hyperspace.” Yes it feels good. Do we get more than this ignition of the joy and memory from DFW?

DeLillo…early books I think are great, End Zone, White Noise, Players, Great Jones Street, the Names. After Libra and Mao II – he pushed out the exaggeration into a plane like satire but not targeted – I didn’t connect to them. Perhaps it’s me.

Fiction.

Fifty Shades of Grey.

It’s this: http://youtu.be/fWNaR-rxAic

David Foster Wallace – yes, yes, yes.

Guy-Z – why do you find him annoying?

Molly – I’m never going to convince you to like him, but that’s fine, he’s not for you. He changed my the trajectory of my career as a writer and filmmaker and even just as a person. I learned more about compassion from a single speech of his than I have from 12 years of Catholic school. Most make him out to be about sarcasm or meta literary gymnastics, but all his writing (with possible exception of his first novel The Broom of the System) strove to convey a level of sincerity, free of irony and disillusion and even intellect. He LONGED to love and to connect.

Like John, I don’t have the energy to defend him, but I will say that DFW reached deeper and deeper into the American post-modern consumer soul (or lack thereof) and what he found, especially within himself, was an exponential emptiness from which he could not save himself. His major problem was the he was so incredibly self-aware of being self-aware, which put him at odds with in our world of self-centered but not self-aware people. I can only guess his life seemed like a fraudulent facsimile of a facsimile of a facsimile of facsimile until he reached true and utter despair. Read the short story Oblivion. Read his essay An Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. Read the James O. Incandenza’ filmography section of Infinite Jest (an example of a film: people watching themselves watching a film about themselves watching it live – the film finished when the audience left the theater).

I am also completely in awe of Roberto Bolaño. He and DFW are much closer than they are made out to be. Like distant cousins, the white dude from Indiana and the smoking poet from Chile. Both tapped into a kind of plague of consciousness that afflict contemporary audiences – especially the fear of boredom. They could have only existed now – as much a product and antidote of the times. Bolaño’s work is a violent denunciation of Latin (European and American) intellectualism and machismo. He’s made me feel more ashamed and proud of being Latin than 12 years of Catholic school. Bolaño knew that evil, great evil of the world, lurks in all of us. And he came close to revealing those evils. Read 2666 – an almost sacred text for me, which reads almost like the bible. Read the short story “Last Evenings on Earth.” Read The Savage Detectives.

A quick anecdote on DWF and Franzen. Franzen is a self-referred “disciple” of DFW and has written several articles in the New Yorker (yuck!) about DFW. In one, he mentions he asked DFW to sign a copy of his book. DFW drew a picture of a cock and balls that spanned across two pages and signed it “To scale.” Of course, Franzen saw this as DFW’s sense of humor, but it seems soooo appropriate for Franzen’s role in “contemporary” literature.